BEYOND THE NUMBERS

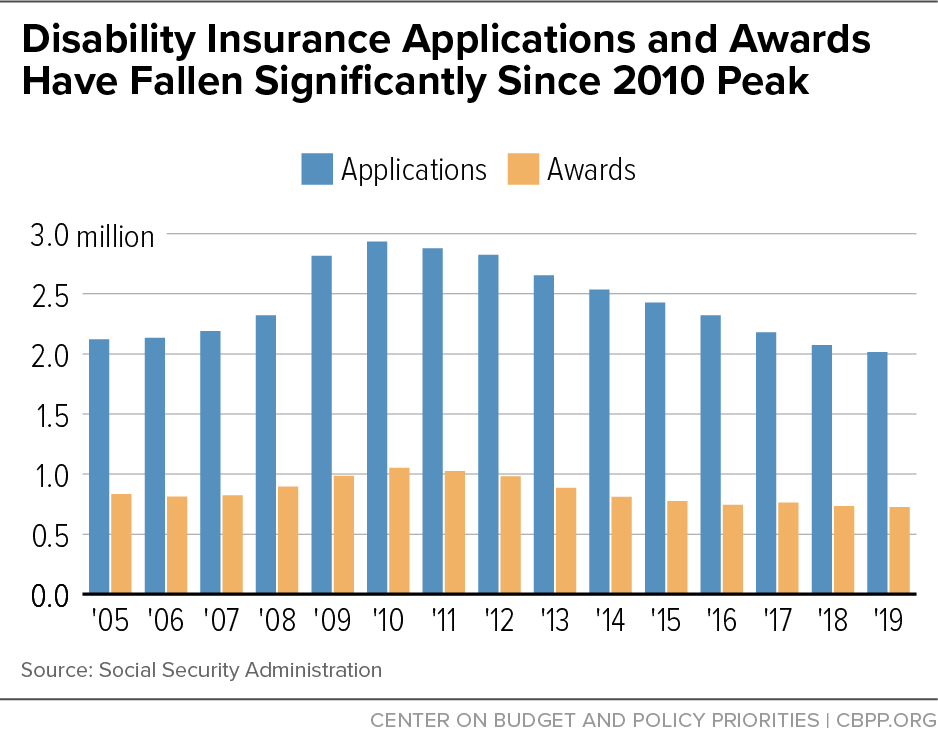

Applications and benefit awards for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) fell again in 2019, new data show, adding to the significant declines since 2010 (see graph). Total SSDI enrollment also has shrunk in recent years — by more than 575,000 people (nearly 6.5 percent) since peaking in 2014.

What’s going on? Nobody knows for sure, but Social Security Administration (SSA) actuaries and researchers have some theories:

- The economic recovery. SSDI applications and, to a much lesser extent, awards respond to the economy. Applications spiked in the Great Recession — just as the baby boomers aged into their 50s and 60s, the peak ages for SSDI receipt — and then fell as the economy recovered. But the recovery can’t fully explain such a large dropoff.

- Lower allowance rates. Applicants that state evaluators initially reject for SSDI benefits can ask for reconsideration and, if they’re denied again, can request a hearing before an SSA administrative law judge (ALJ). About half of claimants who are initially rejected pursue at least one appeal. Allowance rates have fallen slightly at lower levels and sharply at the ALJ stage.

- Discouraged applicants. Filing for SSDI takes real effort and even expense as people track down years of medical records. Although it’s hard to prove statistically, news coverage of long waits, large backlogs, and high denial rates may have deterred some people from applying.

- More access to health care. The Affordable Care Act might have trimmed disability applications modestly by improving people’s health and enabling them to get coverage separately from applying for SSDI. (SSDI recipients qualify for Medicare after two years.) Early studies, though, are inconclusive.

- Fewer SSA field offices. SSA has closed about one-tenth of its field offices since 2000. As we’ve noted, research suggests that field office closures reduce disability applications.

- Fewer personal Social Security statements. Due to budget cuts, few people now get these statements — which show their past contributions and potential benefits — by mail. (People can get the information online, but that’s probably unrealistic for many at-risk workers.) The mailings’ gradual rollout from 1994 to 2004 boosted SSDI applications, a study found, so cutting back the mailings has probably dampened them.

SSDI, a vital protection financed by payroll taxes, helps buffer breadwinners and their families when a severe, long-lasting impairment strikes. The main demographic and program factors driving enrollment are well-known: the growth and aging of the population, the rise in women’s paid work (which means more women are insured for SSDI), and the rise in Social Security’s full retirement age (which keeps people on SSDI longer before they’re switched to Social Security’s retirement rolls and start receiving retirement benefits). But the last few years show that other, less well-understood factors matter, too. Analysts inside and outside SSA should continue to examine them, and policymakers should ensure that severely impaired people who’ve earned SSDI benefits don’t face unnecessary obstacles.