With the baby boom generation now squarely in its peak years for retirement and disability, the demands on the Social Security Administration (SSA) are extraordinarily high. Yet Congress has cut SSA’s core operating budget by 17 percent since 2010, after adjusting for inflation.[1] These cuts hurt SSA’s service to the public in every state. The agency has been forced to shutter field offices and shrink its staff, leading to longer waits for service and growing backlogs. While the overall effect is a decline in service nationwide, the effects of the cuts vary considerably by state.

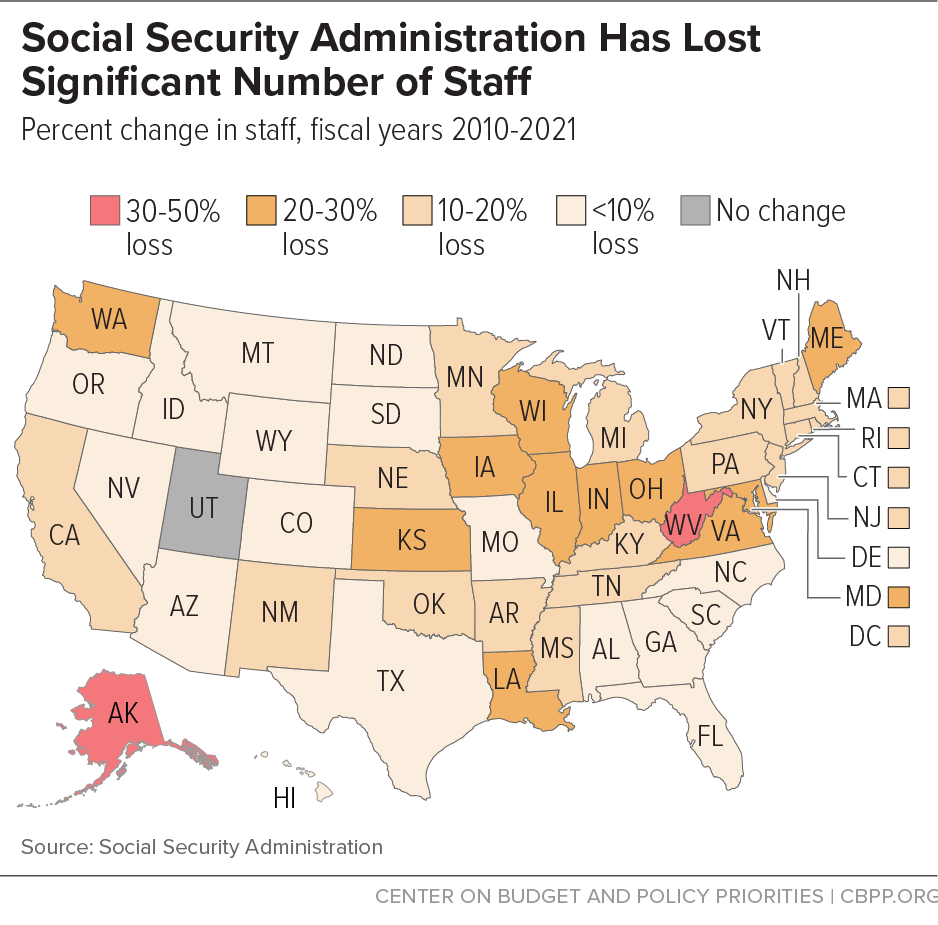

- SSA’s staff shrank by 15 percent nationwide between 2010 and 2021, so there are fewer people to take appointments, answer phones, and process applications for Social Security’s vital retirement, survivors, and disability benefits.[2] As a result, workers and beneficiaries must wait longer to be served. Four states — Alaska, Iowa, Virginia, and West Virginia — and Puerto Rico have each lost more than 25 percent of their staff since 2010.

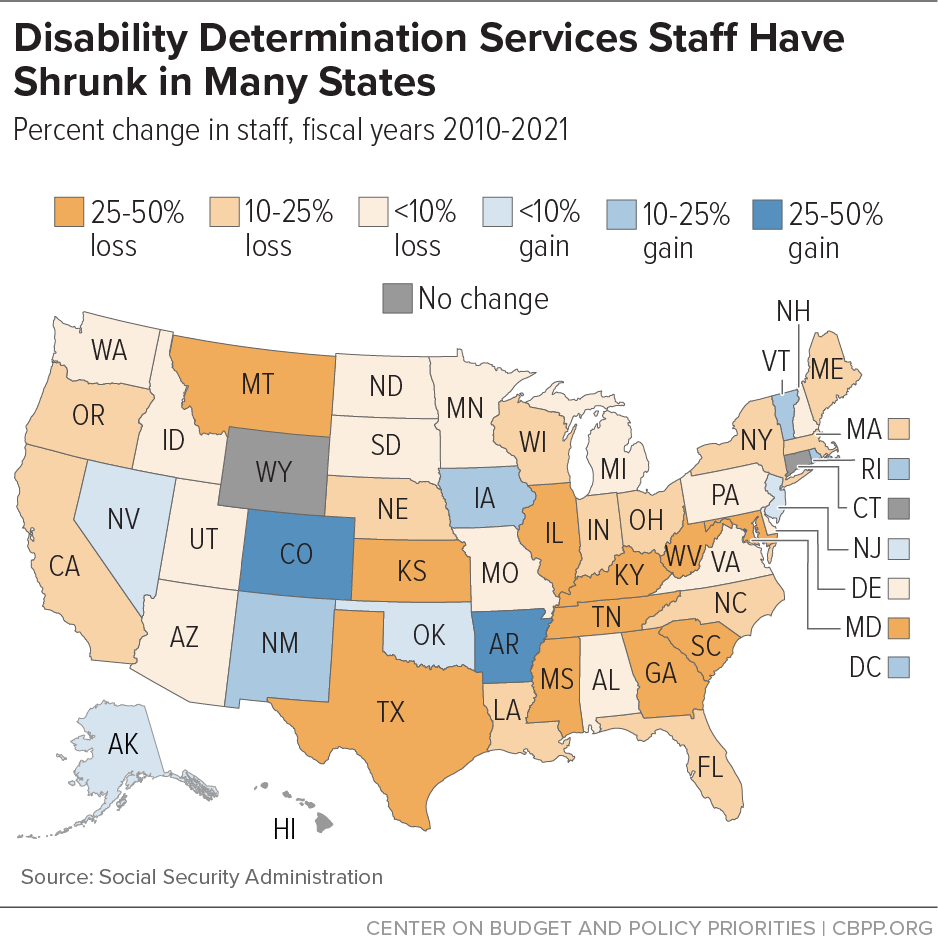

- In addition to its own staff, SSA funds state Disability Determination Service (DDS) employees, who decide whether applicants’ disabilities are severe enough to qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) or Supplemental Security Income (SSI). DDS staff shrank by 16 percent nationwide between 2010 and 2021. Eight states — Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Montana, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia — each lost over 30 percent of their DDS staff.

SSA primarily serves people who are older or disabled, often at difficult moments in their lives such as the onset of a disability or the death of a spouse. Its clients are diverse and include people with cognitive difficulties and people with limited ability to speak English. Its staff provide critical guidance to workers making complex, life-altering decisions. Providing prompt and thorough service reduces errors that SSA staff must fix later. In order to provide good customer service, SSA needs adequate staffing — which requires an increase in funding.

About three-fourths of SSA’s operating budget goes for staff, and the majority of SSA’s staff provide direct service to the public. As a result, funding cuts unavoidably result in service gaps. Tight budgets have forced SSA to cut staff by attrition, which results in uneven patterns across the country.

SSA’s front-line staff serve tens of millions of Americans every year. Its national toll-free telephone number serves as the gateway to the agency’s services, fielding 31 million calls in 2021.[3] Here, trained agents provide services such as answering questions about SSA’s programs, taking claims for retirement benefits, and setting up appointments.

SSA also maintains a network of over 1,200 field offices across the country. Field office staff served 43 million applicants and beneficiaries in 2019, before SSA closed the office to in-person service due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and are again serving the public in person this year. Field office staff take claims for Social Security and SSI benefits, provide replacement Social Security cards, and process name changes. They offer personalized information for applicants navigating complex decisions about when to retire, and make decisions about whether beneficiaries are capable of managing their own finances. In addition, they enroll beneficiaries in Medicare and its Extra Help program for low-income beneficiaries, and help beneficiaries apply for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps).

SSA’s behind-the-scenes work is equally important for ensuring prompt and accurate service. SSA’s payment service centers handle tasks such as awarding widows’ benefits when their spouses die, issuing back payments for SSDI beneficiaries who waited a year or more for a hearing, and resolving complex claims issues.

SSA also funds state DDS employees, who decide whether applicants’ disabilities are severe enough to qualify for SSDI or SSI benefits.[4]

Budget cuts have forced SSA to shrink its staff. As a result, SSA staffing is at its lowest level in 25 years, and the agency is currently under a hiring freeze because of insufficient funding.[5] SSA lost roughly 11,000 employees between 2010 and 2021 and expects to lose another 4,500 front-line employees this year.[6] State DDSs lost roughly 2,500 employees between 2010 and 2021 and attrition over the past year is over 25 percent.[7] Inevitably, understaffing means that beneficiaries must wait longer to be served. The average processing time for an initial disability claim had held fairly steady in recent years at three to four months, but has been rising and reached over six months in April 2022.[8] One million applicants awaited a decision on their disability benefit applications as of April 1, 2022.[9]

SSA and DDS staff losses are spread unevenly across the nation, as Figures 1 and 2 and Appendix Table 1 show. While SSA’s staff nationwide shrank by 15 percent between 2010 and 2021, the declines in Alaska, Iowa, Puerto Rico, Virginia, and West Virginia each exceeded 25 percent. Similarly, DDS staff nationwide shrank by 16 percent over that period, but Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Montana, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia each lost more than 30 percent.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

| Social Security and Disability Staff Changes by State |

| |

| |

FY 2010 |

FY 2021 |

% Change |

FY 2010 |

FY 2021 |

% Change |

| Alabama |

2,713 |

2514 |

-7% |

365 |

362 |

-1% |

| Alaska |

76 |

38 |

-50% |

23 |

25 |

9% |

| American Samoa |

5 |

5 |

0% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Arizona |

706 |

679 |

-4% |

223 |

220 |

-1% |

| Arkansas |

534 |

437 |

-18% |

404 |

543 |

34% |

| California |

6,991 |

5892 |

-16% |

1,440 |

1287 |

-11% |

| Colorado |

705 |

658 |

-7% |

117 |

157 |

34% |

| Connecticut |

403 |

332 |

-18% |

114 |

114 |

0% |

| Delaware |

110 |

102 |

-7% |

41 |

37 |

-10% |

| Dist. of Columbia |

239 |

202 |

-15% |

49 |

57 |

16% |

| Florida |

2,753 |

2601 |

-6% |

1,045 |

852 |

-18% |

| Georgia |

1,777 |

1604 |

-10% |

523 |

354 |

-32% |

| Guam |

13 |

16 |

23% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Hawai’i |

135 |

123 |

-9% |

42 |

42 |

0% |

| Idaho |

149 |

140 |

-6% |

63 |

61 |

-3% |

| Illinois |

3,422 |

2725 |

-20% |

515 |

333 |

-35% |

| Indiana |

925 |

717 |

-22% |

328 |

260 |

-21% |

| Iowa |

343 |

243 |

-29% |

129 |

155 |

20% |

| Kansas |

333 |

256 |

-23% |

104 |

53 |

-49% |

| Kentucky |

825 |

703 |

-15% |

424 |

315 |

-26% |

| Louisiana |

799 |

611 |

-24% |

287 |

233 |

-19% |

| Maine |

209 |

167 |

-20% |

58 |

52 |

-10% |

| Maryland |

12,749 |

10173 |

-20% |

232 |

163 |

-30% |

| Massachusetts |

1,200 |

1020 |

-15% |

250 |

218 |

-13% |

| Michigan |

1,543 |

1275 |

-17% |

594 |

542 |

-9% |

| Minnesota |

493 |

411 |

-17% |

182 |

167 |

-8% |

| Mississippi |

639 |

522 |

-18% |

320 |

225 |

-30% |

| Missouri |

2,784 |

2511 |

-10% |

361 |

332 |

-8% |

| Montana |

125 |

113 |

-10% |

46 |

29 |

-37% |

| Nebraska |

182 |

151 |

-17% |

77 |

67 |

-13% |

| Nevada |

265 |

264 |

0% |

95 |

100 |

5% |

| New Hampshire |

151 |

132 |

-13% |

51 |

49 |

-4% |

| New Jersey |

905 |

799 |

-12% |

298 |

306 |

3% |

| New Mexico |

961 |

801 |

-17% |

86 |

103 |

20% |

| New York |

4,099 |

3619 |

-12% |

934 |

711 |

-24% |

| North Carolina |

1,328 |

1309 |

-1% |

679 |

555 |

-18% |

| North Dakota |

95 |

88 |

-7% |

22 |

20 |

-9% |

| Ohio |

1,794 |

1385 |

-23% |

589 |

501 |

-15% |

| Oklahoma |

563 |

462 |

-18% |

308 |

333 |

8% |

| Oregon |

428 |

387 |

-10% |

195 |

166 |

-15% |

| Pennsylvania |

4,510 |

3918 |

-13% |

704 |

658 |

-7% |

| Puerto Rico |

* |

328 |

|

142 |

108 |

-24% |

| Rhode Island |

166 |

148 |

-11% |

47 |

53 |

13% |

| Northern Mariana Islands |

6 |

5 |

-17% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| South Carolina |

661 |

605 |

-8% |

403 |

239 |

-41% |

| South Dakota |

94 |

87 |

-7% |

33 |

32 |

-3% |

| Tennessee |

1,073 |

934 |

-13% |

533 |

335 |

-37% |

| Texas |

3,477 |

3279 |

-6% |

1,034 |

618 |

-40% |

| Utah |

176 |

176 |

0% |

73 |

72 |

-1% |

| Vermont |

62 |

53 |

-15% |

34 |

38 |

12% |

| Virgin Islands |

12 |

11 |

-8% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Virginia |

2,193 |

1616 |

-26% |

447 |

426 |

-5% |

| Washington |

1,627 |

1264 |

-22% |

318 |

297 |

-7% |

| West Virginia |

454 |

303 |

-33% |

227 |

153 |

-33% |

| Wisconsin |

724 |

553 |

-24% |

233 |

201 |

-14% |

| Wyoming |

44 |

40 |

-9% |

15 |

15 |

0% |

| Total |

70,202* |

59,507 |

-15% |

15,856 |

13,344 |

-16% |