BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Food Insecurity Increased in 2022, With Severe Impact on Households With Children and Ongoing Racial Inequities

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) released its annual report on food security, showing that 44.2 million people (in 17.0 million households) in the U.S. could not afford enough food to eat at some point in 2022. Overall, food insecurity increased from 10.2 percent in 2021 to 12.8 percent in 2022 — resulting in 10.3 million more people, including 4.1 million more children, who lived in households that experienced food insecurity in 2022 compared to 2021 — reflecting higher food costs and the phasing out of many pandemic relief measures.

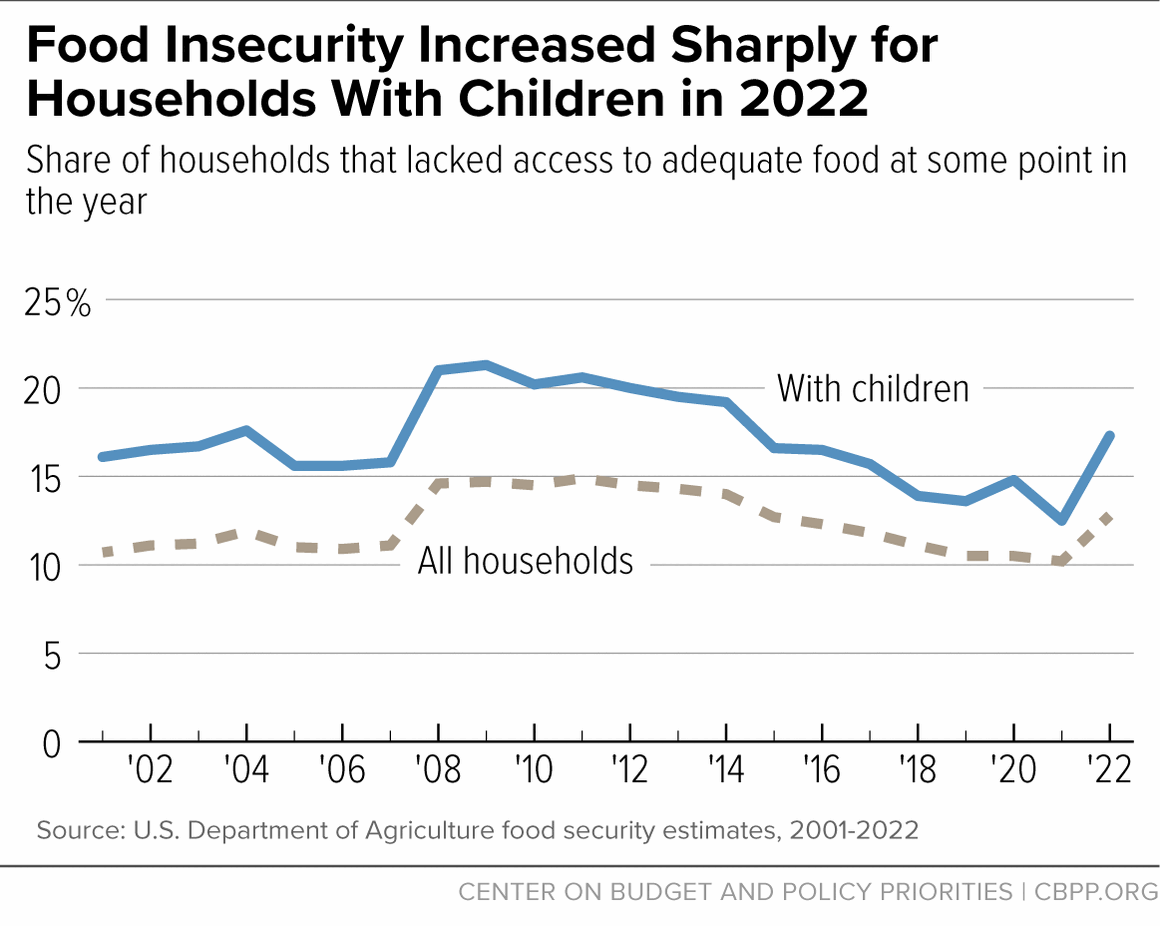

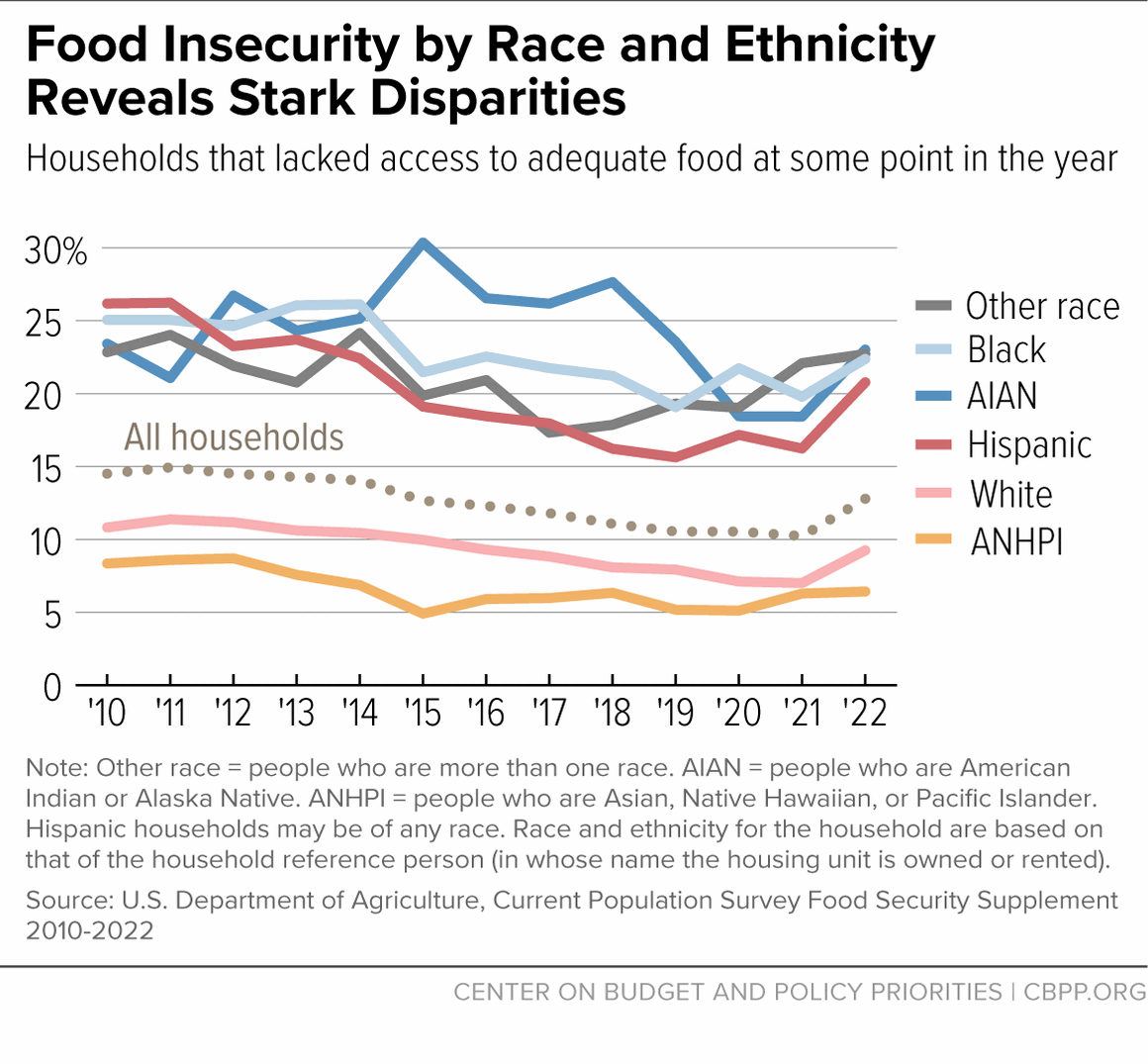

Food insecurity continues to be substantially higher for households that are American Indian or Alaska Native, Black, Hispanic, or multiracial compared to households overall, showing stark inequities. Additionally, food insecurity was more severe for households with children in 2022, a setback from food insecurity reaching a two-decade low for families with children in 2021. This builds on recent Census data that show the country experienced the largest one-year increase in history in overall poverty and child poverty in 2022, driven by the expiration of pandemic relief — including the expanded Child Tax Credit.

Policymakers currently are considering some proposals that would exacerbate food insecurity in the coming years. For example:

- Some lawmakers are reportedly considering undoing in the upcoming farm bill a bipartisan provision that requires future science-driven updates to the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), which is used to set Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit levels. This would cause SNAP to become increasingly outdated and out of alignment with nutrition science, food consumption patterns, and other factors.

- The House agriculture appropriations bill includes provisions that would take SNAP benefits away from more than 1.3 million individuals by further expanding the number of people subject to SNAP’s long-standing, harmful, and failed work-reporting requirement to people who live in areas with relatively high unemployment.

- The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is also in danger of turning eligible people away in fiscal year 2024 — for the first time in more than 25 years — unless Congress ensures sufficient funding levels. So far, Congress has advanced WIC funding proposals that fail to fully fund the program.

Congress should reject proposals that would increase food insecurity.

What might have been behind higher food insecurity in 2022? First, food costs increased sharply in 2022 — by 12 percent from December 2021 to December 2022 — and earlier research shows rapidly rising food prices resulted in greater food hardship for many people. In addition to the end of the expanded Child Tax Credit, mentioned above, temporary pandemic SNAP benefits, known as emergency allotments (EAs), ended in eight states in 2021, and over the course of 2022, nine more states stopped issuing them. Pandemic-related waivers that had allowed most schools to provide free school meals to all students ended at the start of the 2022-2023 school year, so some eligible children in low-income families may have missed out if their families did not know they needed to apply for free or reduced-price school meals. Each of these factors possibly reduced the financial resources available to people with low incomes to afford basic needs, including groceries.

At the same time, several measures may have prevented food insecurity from being even higher. 2022 was the first full year since USDA revised the TFP, the basis of SNAP benefit levels, following a directive from the bipartisan 2018 farm bill to reevaluate the TFP. The revision increased SNAP benefits by about $1.20 per person per day in fiscal year 2022, which began in October 2021 — a modest increase to just $5.45 per person per day, but one that better aligned SNAP benefits with the cost of a healthy diet according to modern dietary recommendations.

Additionally, most states were still issuing EAs in 2022, providing participants in those states with additional SNAP benefits to purchase food. Pandemic EBT grocery benefits were available to school-age children, as they had been for the summer of 2021, to compensate for the free or reduced-price school meals they missed when schools were closed for the summer. Finally, WIC may also have been a buffer for families with children under the age of 5 because it provides set quantities of food regardless of inflation (such as four gallons of milk or 36 ounces of cereal), and participation increased over the course of 2022.

Prior to the pandemic, food insecurity had been decreasing from its peak in 2011 (14.9 percent) and remained steady into 2020 (10.5 percent) and 2021 (10.2 percent), demonstrating the effectiveness of responsive relief programs. The fact that it increased to 12.8 percent in 2022 suggests changes in food prices and relief programs placed additional burden on households in affording food. Food insecurity for households with children had also been going down prior to the pandemic. While it increased slightly in 2020 (to 14.8 percent compared to 13.6 percent in 2019), it went down to a record low of 12.5 percent in 2021, likely due to relief programs for households with children. This progress has reversed, with 17.3 percent of households with children facing food insecurity in 2022 — an increase of nearly 5 percentage points, or almost 40 percent.

As noted above, the data also show racial inequities in food insecurity that have persisted for more than two decades. In 2022, food insecurity for households that were American Indian or Alaska Native, Black, Hispanic, or multiracial (23.0 percent, 22.4 percent, 20.8 percent, and 22.7 percent, respectively) was more than double the rate for white households (9.3 percent). It was 6.4 percent for households that were Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander — whose grouping, due to data limitations, may obscure higher rates of hardship for some subgroups.

These inequities reflect the impact of systemic racism and discrimination in root causes of poverty such as housing, health care, education, and employment, which people of color are more likely to face and which make it difficult to afford enough food to eat. Research shows that SNAP is effective in reducing racial inequities in food hardship and poverty for Black and Hispanic households — and that the TFP revision has contributed to progress, too — but more is needed to strengthen SNAP and reduce racial inequities in affording groceries.

Policymakers have an opportunity in the upcoming farm bill and fiscal year 2024 appropriations to ensure that there are no more harmful cuts to SNAP and that WIC is able to continue providing the current science-based food benefits to all eligible applicants. In the face of greater food hardship, it’s important to increase access to SNAP and WIC for low-income people and to build on the improvements in benefit adequacy from the SNAP TFP revision.