BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Food Insecurity at a Two-Decade Low for Households With Kids, Signaling Successful Relief Efforts

The latest annual Agriculture Department (USDA) report shows that some 13.5 million households with 33.8 million people were food insecure at some point during 2021. The data tell two stories: on one hand food insecurity remains too high, and it’s higher both for households with children than without and for those with members of color than for white households. But overall food insecurity in 2021 was statistically unchanged from 2019 and 2020, even amid a pandemic; it improved for households headed by a Black adult; and it reached a two-decade low for households with children — thanks largely to relief efforts that point the way to further progress.

About 10.2 percent of U.S. households were food insecure in 2021, meaning they struggled to afford enough food for an active, healthy life year-round. That the rate held steady during the pandemic — when accounting for statistical noise it’s not significantly different from the 10.5 percent rate for 2019 and 2020 — is a testament to robust relief measures policymakers enacted. These include Economic Impact Payments, an expanded Child Tax Credit, improved unemployment insurance, and expanded food assistance, along with SNAP’s built-in ability to respond to increased need. Such relief efforts are in contrast to the Great Recession, when the share of food-insecure households rose from 11.1 percent in 2007 to 14.7 percent in 2009 amid a less robust policy response.

But far too many households still face food insecurity. About 1 in 8 households with children (12.5 percent), and slightly more than 1 in 8 households with young children (12.9 percent), were food insecure in 2021, compared to 1 in 11 households without children (9.4 percent).

Though parents and other household members often protect children from food insecurity, children experienced food insecurity in about 2.3 million households (6.2 percent of households with children), and 274,000 children lived in households where children experienced very low food security (they were hungry, skipped a meal, or didn’t eat for a whole day). High prevalence of food insecurity among children is particularly concerning because it’s linked with a number of negative outcomes, like long-term neurological damage and behavioral and mental health issues.

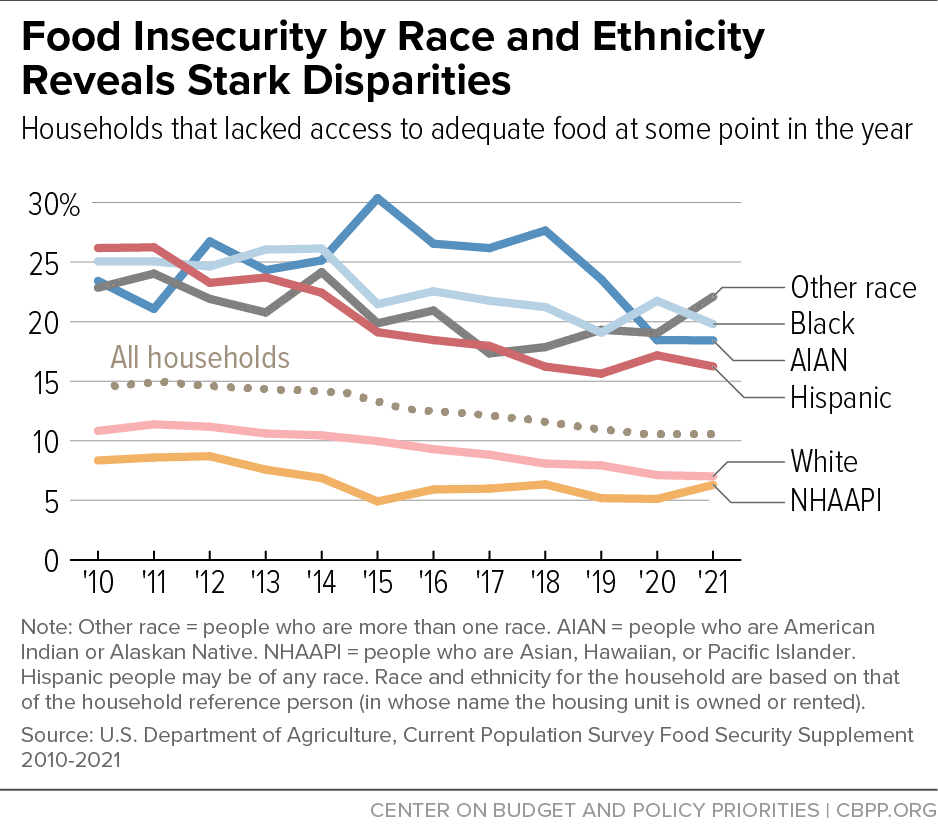

Indigenous people and people of color also face higher levels of food insecurity, and have done so for some time. (See graph.) In 2021, food insecurity affected about 20 percent of households headed by a Black adult, 18 percent headed by an American Indian or Alaska Native adult, and 16 percent headed by a Hispanic adult — all more than twice the share of households headed by a white adult (7.0 percent).

But again there’s also evidence of progress. Even as 12.5 percent of households with children were food insecure, and 6.2 percent of households had food-insecure children, both rates were at (or matched) their lowest levels since before 1998. And food insecurity declined in 2021 both for all households headed by a Black adult, from 21.7 percent to 19.8 percent, and for such households with children, from 27.3 percent to 22.7 percent, respectively. Both drops followed rises the year before.

A significant likely reason for these declines, and for the fact that food insecurity didn’t worsen overall, is important relief measures taken in 2021. They included both broad-based policies, like Economic Impact Payments, and policies that targeted those with the greatest needs, like expanding access to unemployment benefits and increasing benefit levels, expanding SNAP benefits and getting food assistance to children missing out on school meals through Pandemic EBT (P-EBT), helping people at risk of eviction, and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit. (While the child credit expansion was broad based, it also made the full credit available to the lowest-income children for the first time.)

There’s growing evidence that the expanded Child Tax Credit mitigated food hardship among those who received it. Among households without children and therefore ineligible for the credits, food insecurity rose from 8.8 percent to 9.4 percent. Measures targeting those facing the greatest need were critical in preventing spikes in poverty and hardship; they also helped promote equity amid a pandemic and economic crisis that hit households with children and Black, Indigenous, and Latino people particularly hard.

As we’ve written before, decreases in food hardship among households with children coincided with the expanded Child Tax Credit in 2021. While further research is needed, emerging evidence shows the significant impact of relief measures like the expanded Child Tax Credit, SNAP benefit increases, and P-EBT. For example, the Urban Institute estimates that in the fourth quarter of 2021, the SNAP benefit increases (due to the reevaluated Thrifty Food Plan and emergency allotments) reduced poverty by 14.1 percent in states with emergency allotments. And while there was significant poverty reduction across all racial and ethnic groups, the reduction was greatest for Black and Hispanic people.

Although food insecurity held stable in 2020 and 2021, signs over the past year have indicated that more people are struggling to afford enough food, coinciding with high inflation and the end of many of the federal pandemic relief measures. Less detailed weekly data on food insufficiency (a different measure of food hardship) from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey shows that the number of people who report not getting enough to eat in the last seven days has been rising since August 2021. (Note that, due to methodological differences, Pulse shows a higher prevalence of food hardship than USDA’s annual data.) With need likely rising, it’s important that policymakers heed the evidence showing the effectiveness of recent relief efforts and make the investments needed to reduce food insecurity.