Many communities across the United States are considering new approaches to public safety that go beyond traditional policing, and the federal American Rescue Plan has given them a unique opportunity to make progress. The American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021, includes additional federal Medicaid funds for mobile mental health intervention services; education funds that can be used to replace school police and reform punitive discipline policies; housing funds that can be used to reduce homelessness and create more stable communities; and billions in flexible funding that states and localities can use to recover from the pandemic and to support communities hit hardest. These resources can be used to invest in proven community-based approaches to public safety, shift some responsibilities from police to other government agencies, and make additional investments in their residents to foster stable communities.

These investments can improve public safety and public health. Non-law enforcement approaches to issues such as mental health crises, substance use, traffic safety, or school safety — treating them as health, transportation, and education issues — have the potential to address them more effectively than law enforcement strategies and to achieve better outcomes. Shifting to policing alternatives also can address racial and other inequities in the criminal legal system, reducing unnecessary police stops that too often escalate and result in arrests and incarceration that disproportionately target people of color and communities that have been marginalized. Limiting interactions with police also can reduce acts of police violence or other avoidable harm that also disproportionately fall upon people of color, particularly Black people, and on people from communities that have been marginalized.

As states and localities grapple with the best ways to create safe communities, considering both the role of police and alternatives to traditional policing, the Rescue Plan offers resources that can help make new approaches possible. The Rescue Plan provides funds targeted for specific purposes, as well as flexible State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds intended to help states and localities rebound from the pandemic.

- Mobile mental health crisis services. Many communities send police to respond to reports of individuals in mental health crisis, rather than responding with health care professionals. These contacts result in arrests and incarceration more often than is necessary, rather than in appropriate treatment, because police are not health professionals and often have limited training to engage effectively with people with mental illnesses or to de-escalate situations involving them. The American Rescue Plan encourages states to fund mobile mental health crisis intervention services through Medicaid, with the federal government providing 85 percent of the costs for three years, starting in 2022. The Rescue Plan also provides $1.5 billion in funding to states for community-based mental health services. States and localities can also use their Fiscal Recovery Funds to support crisis services for people who are not eligible for Medicaid.

- Better treatment and services for people with substance use disorders. Investing more in substance use services would help ensure people get needed treatment and limit the chances that substance use disorders result in arrest or incarceration. In addition to using their Fiscal Recovery Funds, states can use $1.5 billion provided in the Rescue Plan specifically to support the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders.

- Alternatives to police in schools. The Rescue Plan provides $122 billion to school districts and state education departments, most of which can be used flexibly to advance goals of federal education legislation. These funds can be used to support mental health services in schools, as well as to help school districts develop and fund alternatives to traditional discipline, which disproportionately affects students of color and other marginalized groups and contributes to involvement in the criminal legal system at an early age. Alternatives include positive behavioral supports, trauma-informed training for staff, and restorative justice. These services, which would be helpful in any school, would be especially important in schools seeking to remove a police presence.

- Shifting services currently provided by police to other public agencies. The Rescue Plan’s Fiscal Recovery Funds can be used to address the public impacts of the pandemic, including a rise in violence, by supporting violence interruption services that work to address issues of stress in communities with a high rate of violence before they require police intervention. The Fiscal Recovery Funds also include a provision that allows states to spend some of this aid to replace revenue lost in the pandemic. State and local governments could use these funds to create new non-police units to manage traffic control, reducing the most common police interaction with the public and one that disproportionately targets people of color.

- Affordable housing. Increasing access to decent affordable housing contributes to more stable communities and to lower crime rates. Housing for people returning from incarceration can be especially important to reducing recidivism. The Rescue Plan provides targeted funds to prevent evictions, fund affordable housing, and reduce homelessness. Fiscal Recovery Funds also can be devoted to affordable housing.

- Other investments to create stable communities. States and localities can use their federal relief funds for a variety of investments in low-income communities, such as out-of-school-time programs, nutrition assistance, job training, and subsidized jobs. These investments in people and communities help create stable and safe communities.

Nearly all policing expenses are covered by local governments — cities and counties — but state governments also should have an interest in these investments. The policing alternatives highlighted here would improve health, education, and job outcomes, creating stronger state economies. Investments in policing alternatives also can play a role in reducing incarceration and criminal justice monitoring, where the costs more heavily fall on state governments. In most cases, states and localities have several years to spend their Rescue Plan funds. This gives states a long runway to use federal resources to initiate these transformative public safety approaches, and time to plan for maintaining these programs with their own resources when the federal funds are no longer available.[1]

Cities and States Should Consider Non-Police Approaches to Public Safety

Many communities across the U.S. are engaged in debates about the best ways to keep residents safe amid broader awareness of the problems of policing, but also in response to concerns about recent increases in violent crime. These communities are evaluating the proper role of policing, possible reforms to hold police more accountable, and non-police approaches to some aspects of public safety.

There are several reasons to consider alternatives to police for some aspects of public safety, particularly responding to situations that do not involve imminent threats of serious violence. A law enforcement response is not the most effective in all situations, such as addressing people in mental health crisis, promoting traffic safety, or creating a safe and positive environment in schools. Beyond that, policing in the United States is steeped in a history of racism and continues to disproportionately target people of color, immigrants, LGBTQ people, and other populations that have been marginalized. Inappropriate police use of force, most notably police killings of unarmed Black and brown people, makes communities less safe, and many current policing practices contribute to disproportionate arrests, convictions, and incarceration of people of color, and to the United States’ high rate of incarceration.

- Black people nationally are twice as likely to be shot and killed by police than white people, and Latino people are also killed disproportionately.[2]

- Enforcement of laws on drug use, traffic enforcement, sex work, and gun laws disproportionately targets people of color and the LGBTQ community, particularly homeless LGBTQ youth and transgender people. For example, arrests for drug use or sales are much higher for Black people than white people, even though the rate of drug use is similar across all racial and ethnic groups.[3] Black and brown people are more likely to face police interaction, more likely to be arrested, and more likely to be sentenced to prison or jail.[4] Some 21 percent of Black transgender women will face incarceration at least once in their lifetimes, a rate significantly higher than the general population.

- Disproportionate judicial involvement starts in schools — known as the school-to-prison pipeline — with Black and brown students and students with disabilities more likely to face discipline such as suspension, expulsion, school arrests, and referrals to law enforcement than white students and students without disabilities. Nationally, Black students were arrested 3 times more than white students, while Native American and Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian students were arrested 2 times more, and Latino students were arrested 1.3 times more. Students with disabilities were arrested 2.9 times more than students without disabilities.[5]

- Systemic racism in our criminal justice system has contributed to the United States having the highest incarceration rate in the world. The U.S. has 4 percent of the world’s population but about 20 percent of prisoners.[6]

In addition, policing and costs associated with incarceration consume a substantial share of local budgets. Alternatives to policing often have lower costs, particularly if they help reduce incarceration. Investing in policing alternatives thus could generate budgetary savings at the state and local levels.[7]

State and local governments spend more on the criminal legal system than on many other critical services and programs. Overall, police spending was $119 billion, or 4 percent, of state and local general expenditures in 2018. This was more than they spent on housing and community development, cash assistance, or other notable services. Combined police and corrections spending equaled $200 billion in 2018, or 6 percent of state and local level government spending, more than spending on highways and roads.

Policing accounts for a large share of many cities’ budgets. Cities spent an average of 13 percent of their budgets on policing in 2017, compared with states, which spend 1 percent of their budgets for this purpose. In some cities, policing consumes most of the budget. Milwaukee, for example, spends 58 percent of its budget on police.[8] Atlanta spends more on police than on housing and community development and public health combined.[9]

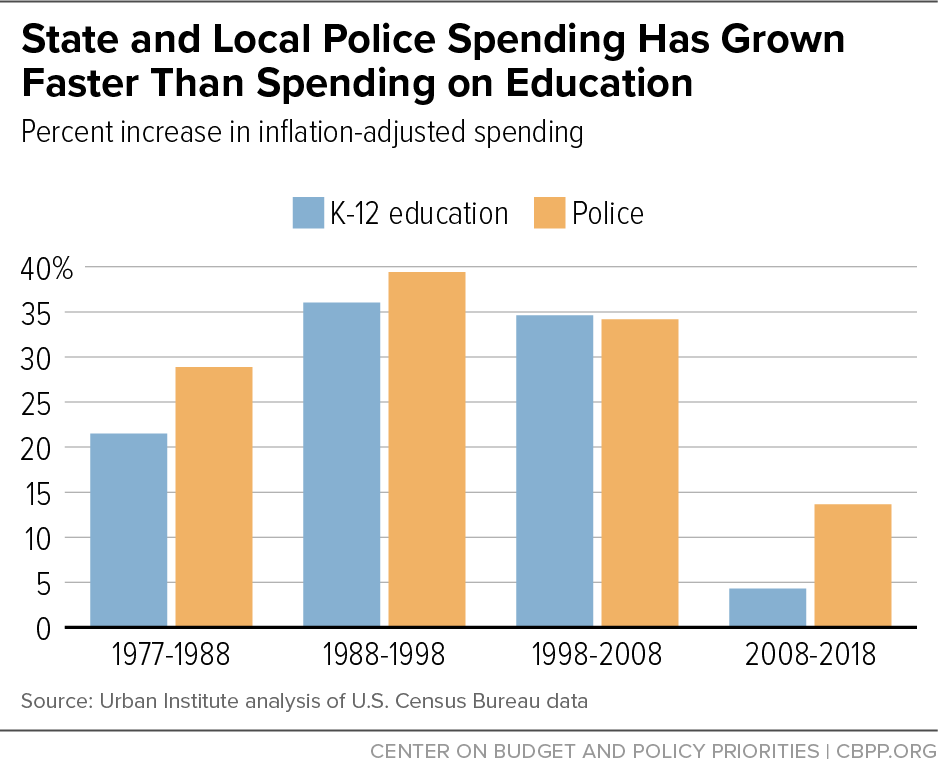

Reflecting a trend in recent decades toward a more punitive criminal legal system, state and local spending on police and corrections has grown faster than spending on K-12 education. The rise in police spending relative to education occurred despite falling rates of violent crimes and property crimes.[10]

- From 1977 to 2018, state and local spending on K-12 education increased 132 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars. Meanwhile, state and local government spending on police increased 174 percent over the same period, from $44 billion to $121 billion (in 2018 inflation-adjusted dollars).

- In the last decade, state and local spending on police increased 14 percent between 2008 and 2018, while spending on K-12 education grew 4 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Spending on corrections (incarceration and other costs related to people in the criminal justice system) has grown even faster. State and local governments spend a substantial amount on correctional facilities, halfway houses, probation monitoring, parole functions, and related services. These expenditures grew more than four-fold from 1977 to 2018, after adjusting for inflation, from $18 billion in 1977 to $81 billion in 2018.

Creating new approaches to public safety that go beyond traditional policing will require new resources. Transferring responsibilities from police to other entities requires money to plan and start those efforts. Community investments to create more stable and safer communities, such as affordable housing, require substantial funding to address these problems on a meaningful scale.

The American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021 to alleviate COVID-19-related hardship and support an equitable recovery, creates a historic opportunity for states and localities to implement new approaches to public safety. It includes several targeted funds — in behavioral health, education, and housing, for example — as well as $350 billion in State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (FRF) that can be used flexibly. Interim guidance from the U.S. Treasury Department, which is administering the Fiscal Recovery Funds, encourages states to spend the funds in ways that help residents hit especially hard by the pandemic and to reduce long-standing economic and racial inequities.[11] For instance, the guidance clarifies that FRF can be used to reduce health inequities across racial and economic lines, and any spending in a low-income Census tract is assumed allowable.[12] Finally, states and localities can use FRF to replace revenues that fell as a result of the pandemic and can spend these dollars on any program or service.

These efforts will likely require greater state government involvement, even though policing is mostly a local responsibility. State governments can provide support, including Rescue Plan funds, to enable and encourage localities to fund police alternatives. State leaders have an interest in public safety reform because it could positively impact state policy, such as through improving state economies and reducing state prison costs.

States have three years or more to spend Rescue Plan funds, depending on the source, and they can use the time during which federal funds are available to plan to maintain those investments with their own resources.

The following describes how Rescue Plan funds can be used to fund a variety of public safety alternatives to traditional policing.

About 10 percent of police contacts involve individuals with mental illness, and 23 percent of people killed by police have a mental illness.[13] Using police to respond to behavioral health crises can criminalize and stigmatize mental illness and substance use disorder, often leading to arrest and incarceration, and make it more likely that the underlying mental illness or substance use disorder remains untreated.[14]

Rather than sending police to calls related to domestic disputes, mental health crises, or other similar situations, mobile crisis intervention programs can send behavioral health care professionals trained in de-escalation to help safely resolve the situation. Under this model, a multidisciplinary mobile crisis unit that includes a behavioral health care professional responds to an individual in crisis. Mobile crisis teams assess and stabilize individuals experiencing behavioral health emergencies in the least restrictive setting and divert individuals with mental illness or substance use disorders from jail and emergency departments to crisis stabilization services and other community-based treatment.

The Rescue Plan allows states to amend their Medicaid programs to fund mobile crisis intervention services. (The option is currently in place for five years, although the Build Back Better Act would make it permanent.) The provision goes into effect in April 2022, and for the first three years a state implements the option, the state would receive an 85 percent federal matching rate. (This is a higher rate than the base federal matching rate, which ranges from 50 percent to as high as 83 percent, based on a state’s per capita income.) To take advantage of this, states will need to amend their Medicaid state plan or apply for a federal Medicaid waiver; 20 states have received planning grants (from $15 million in Rescue Plan grant funds) that they can use to assess the need for mobile crisis services and design their state plan or waiver proposal.[15]

To be eligible for the enhanced Medicaid match under the Rescue Plan, crisis intervention services must:

- Include at least one behavioral health specialist. They also can include nurses, social workers, peer support workers, and others.

- Be run by staff trained in trauma-informed care and de-escalation.

- Be able to refer people to other health and social services they need.

- Be connected to community partners.

- Be available 24 hours per day, seven days per week.

Several states and cities offered these services prior to the pandemic. In 2019, 13 states operated Medicaid-funded mobile crisis programs (at the state’s standard Medicaid match rate), and six other states and localities operated similar programs through non-Medicaid means. For example, Georgia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities provides mobile crisis services on a 24-hour basis using behavioral health professionals and paraprofessionals through its Georgia Crisis and Access Line, which operates separately from 911 call operations.[16]

Another well-known model is CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets) in Eugene, Oregon.[17] The city has funded CAHOOTS since 1989, and it has greatly reduced police engagement. Of the 24,000 calls handled by CAHOOTS in 2019, only 311 ended up requiring police back-up.[18] This also resulted in budget savings for Eugene.[19] Similarly, over the past year, San Francisco, Berkeley, Albuquerque, and St. Petersburg, Florida, have taken steps to use specialized non-police staff to respond to 911 or other police calls related to mental health, homelessness, or drug use.[20]

States and localities can cover mobile crisis intervention services for people who are not Medicaid-eligible using $1.5 billion each in Rescue Plan funding for mental health and substance use services (which can cover a wide range of behavioral health services), as well as Fiscal Recovery Funds.

Crisis intervention services alone will not work to keep people with severe mental health or substance use needs from interaction with the criminal justice system. State and local governments must be able to offer a range of emergency and long-term behavioral health supports, and to address the other stressors that people with mental illness face, for example by helping them find stable housing and employment.

Expanded Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Too often, substance use disorders (SUD) are treated criminally rather than as diseases, especially for people of color.[21] Moreover, most people who need treatment for substance use do not receive it. A comprehensive system of SUD care includes a full continuum of treatment and recovery services, integrated care for co-occurring physical and mental health conditions, and connections to services to meet needs such as housing or employment.

States can use several sources of Rescue Plan funds to provide enhanced support to people with substance use disorders, including supportive services such as housing or job training.

- Medicaid can cover a wide array of clinical SUD treatment services, recovery supports, and other related mental and physical health care. All but 12 states have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to residents with incomes under 138 percent of the poverty line. States considering using Rescue Plan funds for substance use disorder treatment should first ensure that their Medicaid state plan covers these services, because the federal government covers at least half of all Medicaid expenses.[22]

- As described above, the Rescue Plan provides $1.5 billion in funding to states for community-based mental health services, a separate $1.5 billion appropriation for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders, and a $77 million increase in grants through the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic program.

- States and localities can use their Fiscal Recovery Funds for investments in health care, including SUD treatment.[23]

- Treasury’s interim guidance for the Fiscal Recovery Funds encourages states and localities to use the funds for investments in communities hit hardest by the pandemic, such as affordable housing and job training investments that can support SUD recovery.[24]

Other reforms include decriminalizing certain behaviors, such as cannabis and other drug use, in recognition that a law enforcement response to substance use is not the most effective. Decriminalization limits interactions with police, arrests for low-level offenses, pre-trial detentions, and more.[25] Many states, for example, have decriminalized possession of small amounts of cannabis, and some have expunged prior criminal convictions for cannabis possession. In place of prior policies, states can invest more in services that treat substance use as a matter of public health.

Some communities are looking to reduce the role of police in schools or remove them entirely, along with limiting disciplinary practices, such as expulsions and suspensions, that disproportionately are used on students of color, adversely affect a student’s success in school, and contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline. By contrast, school-based mental health staff improve outcomes for students and overall school safety.[26] Recently, communities including Minneapolis, Portland, Seattle, Oakland, and Denver have removed all police from their schools.[27]

The Rescue Plan provides $122 billion for K-12 education, in addition to earlier rounds of pandemic relief funding for education. State education agencies can retain up to 10 percent of the Rescue Plan funds, with at least 90 percent going to school districts.

- Of the 10 percent state set-aside, at least 7 percent must be used to address students’ unfinished learning due to the pandemic through, for example, summer school and afterschool programs.

- 20 percent of funds to school districts must be used to address students’ unfinished learning.

Outside of these requirements, the funds may be used flexibly in ways that are consistent with the purposes of the major federal education programs, creating room for states and school districts to invest in new school initiatives to promote positive behavior in schools and address discipline issues without police.

- States can use their share of funds to help school districts engage in trauma-informed education or plan for restorative justice programs.

- School districts also can use Rescue Plan funds to hire more staff to address social-emotional needs, such as social workers, school psychologists, nurses, and counselors.

- School districts can invest in community-based afterschool activities for students.

Along with these funding changes, school districts can mitigate the school-to-prison pipeline by updating discipline policies to remove elements that have disproportionate impacts on students of color and girls, such as “zero-tolerance” policies that mandate strict disciplinary penalties with little flexibility, and aspects of dress codes that disproportionately affect girls generally and girls of color particularly.[28]

The Rescue Plan provides several sources of funds that can be used to create affordable housing in ways that provide stability and that can reduce interactions with the criminal legal system. Targeted affordable housing can address one of the main challenges to stability that people returning from jail or prison face; a lack of housing options contributes to recidivism rates.[29]

- The Rescue Plan provides $5 billion for housing vouchers for people experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, including survivors of domestic violence. These vouchers are distributed to and controlled by local housing agencies. Use of these vouchers will contribute to more stable communities and therefore support public safety. Housing agencies could further connect these vouchers to public safety by designating a share for people returning from jail or prison who were formerly homeless or are at risk of being homeless upon release.

- The Rescue Plan provides an additional $5 billion to states and localities to build affordable housing, provide tenant-based rental assistance, acquire buildings to use as non-congregate homeless shelters, and provide supportive services.

- State and local governments can use their Fiscal Recovery Funds for affordable housing, as noted in Treasury’s interim guidance.

- States and localities also can use their FRF to invest in homeless-outreach services, as an alternative to having police respond to homelessness-related calls. This would help connect residents experiencing homelessness to services and reduce their risk of arrest and incarceration.

States and localities also can create sustainable solutions to homelessness by reducing reliance on law enforcement to respond to homelessness.[30]Some communities effectively criminalize homelessness by outlawing activities such as sleeping outside, sitting in public, living in cars, or panhandling, and by relying on law enforcement to respond to homelessness. This subjects people to fines or jail time for not being able to afford a place to live. It also makes it harder for people to access housing, in part because public housing agencies and landlords often screen out applicants for criminal records.[31]

The State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds create opportunities for states to fund new entities to take over certain responsibilities from police or provide services that can reduce violence and interventions by police. For example, states can fund new non-police traffic management entities and violence interrupter services.

Non-police traffic management. The most common interactions between police and the public occur through traffic stops. Communities can shift traffic enforcement from police to other agencies that are specifically tasked with traffic safety, rather than law enforcement, which would both improve traffic safety and reduce interactions with the criminal legal system. For example, Berkeley, California is in the process of transferring traffic safety to unarmed non-police personnel, and several other cities are considering similar changes.[32] Other communities, including Minneapolis, are moving to prohibit police from making traffic stops that are not public safety related.[33]

Violence interruption services. Community-based approaches treat violence as a public health issue and use outreach, direct communication, and supportive relationships to engage those at greatest risk of engaging in violence, particularly gun violence. Under this approach, community-based organizations work in communities with high levels of violent crime to identify tensions in the community that could lead to crime and work to resolve them before they escalate. A growing number of cities, including Chicago and the District of Columbia, use violence interrupters.[34] Some violence interruption services have resulted in neighborhood-level reductions in killings and shootings of up to 30 percent.[35]

Treasury’s guidance notes that investing FRF in violence interruption services is allowable as a public health investment to address the public health impacts of the pandemic.

Investments in basic services that support family and community stability, such as affordable housing and job training, contribute to greater public safety, research confirms. These investments support strong communities and reduce stressors that can contribute to community strife and violence. Communities with strong institutions to address violence and promote community well-being have lower rates of violent crime.[36] Increased spending on social services is correlated with substantially lower homicide rates.[37]

More specifically, states that spend more on housing generally have lower incarceration rates, perhaps because affordable and supportive housing programs offer a stable foundation for education, employment, and access to services.[38] Reducing unemployment has been shown to reduce property crimes.[39] Research also shows that increasing access to health care — and specifically to substance use disorder treatment — leads to lower rates of property and violent crime.[40]

State and local governments can use their Fiscal Recovery Funds to support these services. As described above, the interim federal guidance notes that expenditures on affordable housing are allowable, as are expenditures to create healthier environments in low-income Census tracts. As noted, under the provision to use FRF to replace lost revenue, states and localities can spend the funds on any services.

There are many benefits of using federal pandemic relief funds to create or expand public safety approaches that shift some responsibilities from police, invest in new approaches to preventing violence, and focus on family and community stability.

- Improved public safety outcomes. Responding with staff trained and focused on addressing mental health crises, homelessness, and traffic safety makes sense and has shown promise to work better than using law enforcement approaches. Community-based approaches to reducing violence have shown success at reducing gun violence. And investments in housing and employment reduce crime, presumably because they create greater economic security.

- Reduced involvement in the criminal legal system. Investments that support public safety without police can reduce the number of people facing arrest and incarceration. Because criminal justice involvement can have significant and long-lasting adverse effects on affected individuals — including challenges finding housing and employment, and the imposition of unaffordable fees and fines — reducing police engagement in cases where alternatives are available can have beneficial impacts for people who otherwise might unnecessarily or inappropriately face arrest and/or incarceration, as well as for communities and economies.

- Reducing police violence and other harmful police interactions. Shifting police responsibilities to other entities is likely to limit the likelihood of inappropriate responses to moments of crisis, such as arresting people facing a mental health crisis.

- Corrections and police savings. Reducing criminal justice involvement can contribute to efforts to reduce the high rate of incarceration in the United States, reducing costs for state and local governments.

- Stronger communities, stronger economies. Investments in affordable housing, high-quality schools, and job training have tremendous benefits. Affordable housing that reduces the likelihood of frequent moves, eviction, or overcrowding helps adults find and keep jobs and supports children’s educational success. These and other investments to address poverty can improve educational and economic outcomes for children and improve health outcomes for children and adults. Stable affordable housing reduces incarceration rates among children when they become adults.[41]