The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan adopted in March 2021 provides a historic opportunity for states to jumpstart transformative investments in a stronger and more equitable future, especially $195 billion in Fiscal Recovery Funds (FRF) that states can allocate through October 2024. States can use these funds to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in a variety of ways. Federal guidance encourages states to focus on low-income communities and communities of color that were hit hardest by the pandemic, such as by expanding mental health services, providing rental subsidies, or improving access to postsecondary education or job training. Many of the steps to support a strong recovery would also address long-standing economic and racial inequities. Thus, states should look for ways to sustain these improvements over the long term.

Despite this opportunity, some state elected officials have called for a much more limited use of FRF, to projects with one-time costs, such as short-term pandemic relief or capital construction projects. These officials note that federal funds, while available for several years, are not ongoing, leaving states to find ways to maintain programs when the funds run out.[1] However, states that only fund projects with one-time costs — especially those that fail to benefit the communities hardest hit by the pandemic — may miss a historic opportunity to permanently improve the lives of people long neglected by public policies. For example, a limit to one-time costs would prevent states from implementing permanent reforms to strengthen services to address substance use disorders, mental health services for youth, or job training.

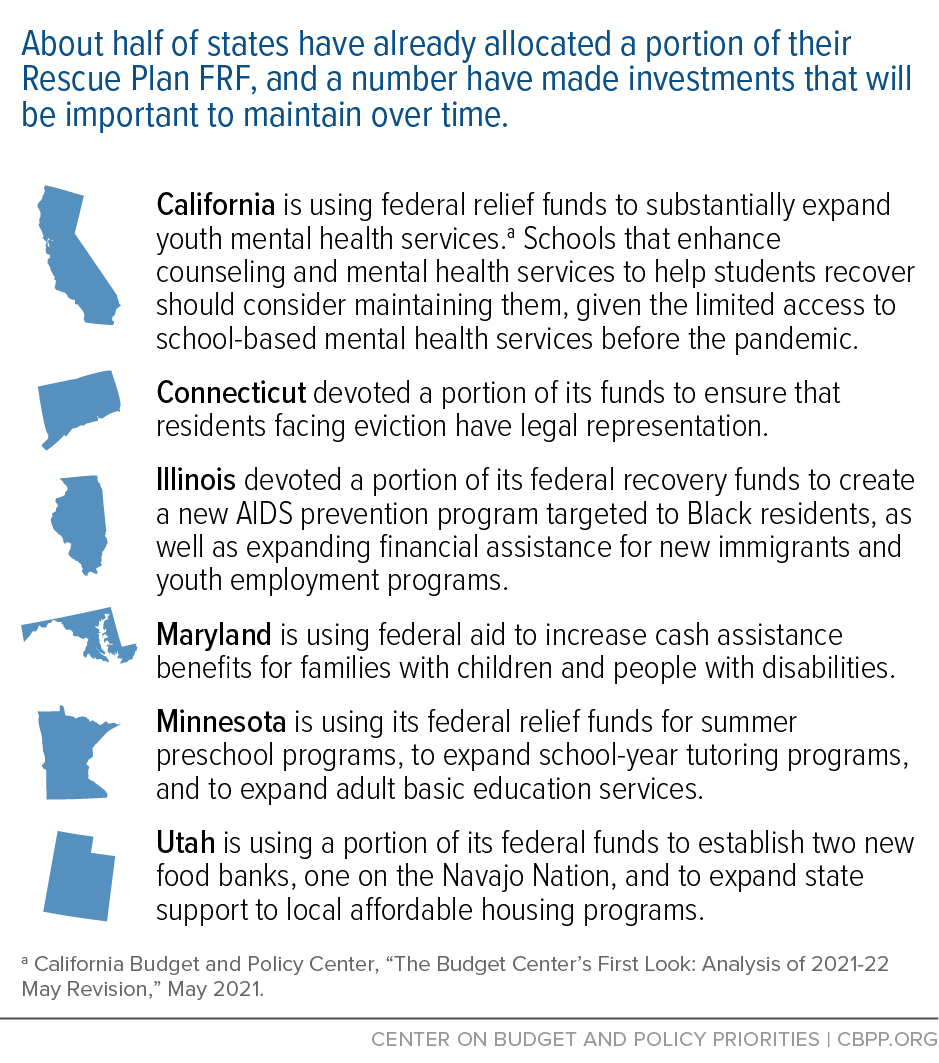

Instead, states should use a portion of their FRF to fund new or expanded initiatives that improve the lives of people in low-income communities. States have until the end of 2024 to use the FRF, giving states over three years of economic and revenue growth before they’ll need to pick up the cost of new or expanded services. They should use the next three years for which federal funds are available to plan to maintain those investments. This will enable states to address the harshest impacts of the pandemic and support a stronger and more equitable economy in the long run. After the Great Recession in 2008, many states cut spending deeply, with limited federal aid, and this hampered their recovery for years.

States will be in the best position to take on new or expanded investments if they have a sound revenue system that is designed to grow at pace with the economy. Yet state revenue systems are falling short in many ways, and policymakers in some states are considering tax cuts that would make it even harder to sustain Rescue Plan-funded investments. To develop stronger revenue systems, states should address structural revenue problems, avoid tax cuts, and raise new revenues, particularly from higher-income residents and profitable corporations.

State budget choices over the next several years will be critical to addressing the ongoing damage and suffering caused by the pandemic. By directing resources to those most in need, making programmatic shifts to address systemic racism, and planning to sustain these investments, states can reduce their deepest inequities and build fairer, stronger, and more resilient communities.[2]

Guidance from the U.S. Treasury Department, which administers the FRF, recognizes that racial and economic inequities pre-dating the pandemic worsened during the health emergency and resulted in especially harmful consequences in low-income areas and communities of color. The guidance encourages states to focus the funds on these communities, for services including education, housing, and mental health.[3] For instance, it clarifies that spending that reduces health inequities across racial and economic groups will be considered an allowable use, as well as any spending in a low-income census tract or spending targeted to households with low incomes. The guidance also encourages states to identify groups of people hit especially hard and to target funds to them.

Beyond that, the guidance notes that many of the pandemic’s harmful impacts may last for an extended period. For example, the guidance notes that many children whose schooling was disrupted during the health emergency will experience long-term incomplete learning that diminishes their prospects. The pandemic’s impacts on mental and physical health, children’s cognitive functioning, and the employability of adults who lost jobs during the crisis may also be long lasting, the guidance notes. Addressing these harms may require sustained investment for many years.

Racial inequities have widened in the pandemic downturn, with Black and Latino people bearing the brunt of the hardship.[4] Shaping these outcomes are structural barriers such as wealth and income disparities, inadequate access to health care, and racial discrimination built into the health system and labor market. These are some ways that states can spend their FRF to reduce racial and economic inequities:[5]

- Permanent supportive housing for people facing chronic homelessness. Permanent supportive housing — ongoing housing assistance with supportive services — has proven highly effective at enabling people facing chronic homelessness to achieve housing stability and to manage chronic health problems, including mental health and substance use disorders.[6]

- Affordable housing. Providing more affordable housing can stabilize families and reduce overcrowding, eviction, and homelessness. Many states support affordable housing construction or programs that help low-income households pay rent for a modest unit of their choice in the private market.[7] Federal legislation under consideration would greatly increase access to rental subsidies for low-income families, but given the tremendous need for affordable housing, there still will be a need for state and local efforts. Currently, only 1 in 4 eligible low-income households in the United States receives housing assistance.[8]

- Subsidized jobs programs. Workers of color, workers without a college degree, women, and immigrants have experienced a disproportionate share of job losses in the last year. Subsidized employment, in which the government temporarily subsidizes some or all of an individual’s wages, can help these workers better weather the economic disruption caused by the pandemic, and potentially get connected to permanent, unsubsidized employment.

- Alternatives to traditional policing. Many communities across the country are considering new approaches to public safety — such as mental health crisis intervention services or violence interruption services — to reduce their reliance on traditional policing, which is marked by a history of racism thar continues to disproportionately target and harm communities of color.

- Behavioral health services. The pandemic has highlighted the limitations in state-level systems to support people with substance use disorder or mental health needs. Investments in these services are important to help residents adversely affected by the pandemic and support a fuller recovery. Maintaining these investments can also help address the systemic limitations that made it difficult to respond to increasing behavioral health needs in the pandemic.

- School-based mental health. The reliance on remote learning during the pandemic has had adverse impacts on children’s socio-emotional development, in addition to causing stress for many students. Students’ educational recovery will require addressing these needs as well as academic needs. Even before the pandemic, many school districts failed to meet recommended staffing levels for counselors, social workers, and other mental health professionals. States can support school districts by providing additional resources to hire staff to address student mental well-being. While the Rescue Plan provided funds for state education departments and local school districts, those funds may not be sufficient to meet the needs of students who suffered the most in the pandemic, given the service gaps that existed before it.

- Aid to high-poverty schools. Students of color from low-income families have suffered the most academically in the pandemic, for reasons including lack of access to high-speed internet or digital technology, inadequate space to study, and lack of access to educational alternatives (such as sharing a tutor in learning pods). Investments in high-poverty communities — for access to high-speed internet, tutoring, or out-of-school activities — can support an equitable recovery from the pandemic and advance education equity in the long term.

States should use a portion of their FRF to invest in new or expanded ongoing initiatives that will support a strong economic recovery and address long-standing inequities in education, housing, health care, employment, and more. The funds can be allocated through December 31, 2024; state economies will likely grow during that period as they recover from the pandemic, and state revenue collections will grow as a result. The states with the healthiest revenue growth will be in the best position to sustain investments funded with FRF.

To be in a strong position to do so, states should take steps to ensure that their revenue systems are healthy. That starts with not adopting tax cuts, especially tax cuts that disproportionately benefit high-income residents, since a substantial share of economic growth across the country is concentrated among high-income residents. Beyond that, states can take steps to strengthen the structure of their revenue systems to make sure it is well connected to the state’s economic activity. Finally, states should consider revenue increases focused on higher-income residents, which would make their revenue systems fairer and provide revenue to sustain federally funded pandemic relief investments.

The Rescue Plan prevents states from making deep tax cuts by reducing federal relief to states that cut taxes deeply.[9] States must maintain their growing tax collections in order to sustain programs funded in the next few years with FRF. However, policymakers in a number of states, including Arizona and Ohio, are considering tax cuts that would limit their long-term opportunities for investment. And leaders in other states have proposed dramatic changes to their tax systems, including proposals to eliminate the income tax in Mississippi and West Virginia. States should not be cutting taxes and instead reserve revenues for services that will support a strong and equitable recovery.

Tax cuts at the state level always limit the ability of the state to make investments that promote a strong economy — such as in education and health care — because states must balance their budgets. Cutting taxes now, as states are making strategic investments to support their pandemic recovery, is even more inadvisable because it would limit states’ ability to maintain those investments.

Revenue systems in many states face a structural deficit, or the chronic inability of state revenues to grow in tandem with economic growth and the cost of government.[10] States have structural deficits largely because they have failed to modernize their revenue systems to reflect far-reaching changes in the economy. The contributors to state structural deficits include:

- The U.S. economy’s shift from goods to services. The increasing importance of the production and consumption of services has reduced the growth of state and local sales tax revenues, because in most states, sales taxes are levied largely on tangible goods and not on services.

- The erosion of state corporate taxes. The global economy has made it difficult for states to identify profits that should be taxable. Moreover, U.S. corporations have exploited their growing mobility by demanding special tax breaks as a condition for maintaining or establishing a location in a particular community.

- The erosion of state income taxes. State income tax structures are much flatter (that is, less progressive) than the federal income tax. Several states have reduced their top income tax rates, further reducing the growth of income tax collections relative to economic growth. This is important because in our unequal economy, revenue growth is concentrated among those at the top.

- States’ adoption of tax and expenditure limitations and supermajority requirements. A number of states have rigid requirements in their state and local fiscal systems, such as constitutional restrictions on taxation and expenditures or supermajority requirements for increases in taxes. These restrictions make it difficult for policymakers to modernize tax codes and adjust to changing budgetary needs.

Addressing these structural barriers to a sound revenue system is always important, but especially now as states work to recover from the pandemic. While state revenues generally came in better than feared early in the pandemic, today they remain down in most states. In 40 states, revenues for fiscal years 2020 and 2021 combined were below levels forecasted before the pandemic, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.[11]

A number of states have taken steps to fix these structural problems — by broadening their sales tax base, closing loopholes in their corporate income tax, creating new personal income tax brackets for higher-income residents, and more. Nevertheless, states can improve in one or more of these areas.

The United States raises much less revenue as a share of the economy than most other industrialized countries.[12] As a result, supports for families and communities and the investments to broaden opportunity are relatively weak, resulting in unnecessary hardship that diminishes quality of life. This is especially important at the state and local level, where governments must balance their budgets each year.

States should consider improvements to their tax systems to raise additional revenue for high-quality schools, health care, and other public investments, helping to ensure that initiatives adopted now with FRF can be sustained. States can raise revenue from the wealthy and profitable corporations. State and local tax systems often ask the least of wealthy, mostly white households as a share of income, thereby worsening disparities in wealth often created or aggravated by racism. States can raise needed revenue and reduce income inequality by better taxing wealth, such as by improving taxation of stock sales, large inheritances, expensive property, and other forms of wealth that often face low tax rates or go untaxed.[13]

States can also remove barriers to revenue raising, such as supermajority vote requirements (which allow a small group of lawmakers to slow or block tax measures that have majority support), limits on income tax rates, and highly restrictive limits on annual spending growth. Some of these barriers emerged from explicitly racist efforts in the past to limit the ability of state governments to fund additional services for predominantly low-income Black communities, and those barriers continue to reinforce racial inequities. Supermajority rules also encourage states to close budget gaps mostly, if not entirely, through spending cuts, which can inhibit recovery.[14]

Another option is for states to roll back economic development incentives and other tax breaks for profitable corporations. Economic development incentives cost states about $45 billion per year, in aggregate, despite evidence that they are largely ineffective.[15] Other tax breaks often reward companies for business activity they would have engaged in anyway or have a low “bang for the buck.” Rolling back ineffective breaks to improve economic supports for people in hard-hit communities of color would also improve racial equity; the corporations that typically benefit the most from these breaks are owned mostly by wealthy and white shareholders.[16]