Unfinished Business From the 2017 Tax Law

Testimony of Chye-Ching Huang, Director of Federal Fiscal Policy, Before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Select Revenue Measures

End Notes

[1] The law’s official name is “Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018.” Its original title, the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” was stricken from the bill.

[2] During the debate over the 2017 law, several of its supporters effectively tried to argue that the true cost of the bill, then estimated at $1.5 trillion, should be reduced by the cost of extenders it did not made permanent. That is even though some of those extenders are now being reconsidered, and even while the law created new expiring provisions. For more on how extenders were considered during the debate on the 2017 tax law, see Seth Hanlon, “Written Statement Before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Tax Policy, Hearing on Post Tax Reform Evaluation of Recently Expired Tax Provisions,” March 14, 2018, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/WM/WM05/20180314/106946/HHRG-115-WM05-Wstate-HanlonS-20180314.pdf; Hanlon, “The Senate Tax Bill Is Even More Costly Under Current Policy Assumptions,” Center for American Progress, December 13, 2017, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2017/12/13/444103/senate-tax-bill-even-costly-current-policy-assumptions/; and Chye-Ching Huang and Brandon DeBot, “‘Current Policy’ Baseline Would Hide $439 Billion in Tax Cuts Worth at Least $40,000 a Year for the Top 0.1 Percent,” CBPP, August 16, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/current-policy-baseline-would-hide-439-billion-in-tax-cuts-worth-at-least-40000.

[3] Sally Persons, “Kevin Brady: House plans to make tax cuts permanent,” Washington Times, July 12, 2017, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/jul/12/kevin-brady-house-plans-to-make-tax-cuts-permanent/.

[4] Chuck Marr, “Republicans Chose Corporate Shareholders Over Working Families,” CBPP, December 19, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/republicans-chose-corporate-shareholders-over-working-families.

[5] Burgess Everett and Rachel Bade, “Tax cuts, Round 2: GOP looks to punish Democrats in 2018,” Politico, March 27, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/03/27/tax-cuts-gop-2018-midterms-482158.

[6] Chye-Ching Huang, “Permanent Extension Would Double Down on 2017 Tax Law’s Fundamental Flaws,” CBPP, May 2, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/permanent-extension-would-double-down-on-2017-tax-laws-fundamental-flaws.

[7] The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in December 2017 that the 2017 tax law would cost $1.5 trillion between 2018 and 2027, but an April 2018 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis raised the cost to $1.9 trillion. CBO, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018-2028,” April 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53651-outlook.pdf.

[8] Chuck Marr and Brendan Duke, “New House Republican Tax Proposal Fails Fiscal Responsibility Test, While Favoring the Wealthiest,” CBPP, updated September 13, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/new-house-republican-tax-proposal-fails-fiscal-responsibility-test-while.

[9] Chye-Ching Huang, “Senate’s Hearing Testimony Highlights 2017 Tax Law’s Fundamental Flaws,” CBPP, April 25, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/senate-hearing-testimony-highlights-2017-tax-laws-fundamental-flaws.

[10] Emily Horton, “Tax Planner: Drive Wealthy Clients Through ‘Gaping Hole’ in Tax Code,” CBPP, May 31, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/tax-planner-drive-wealthy-clients-through-gaping-hole-in-tax-code.

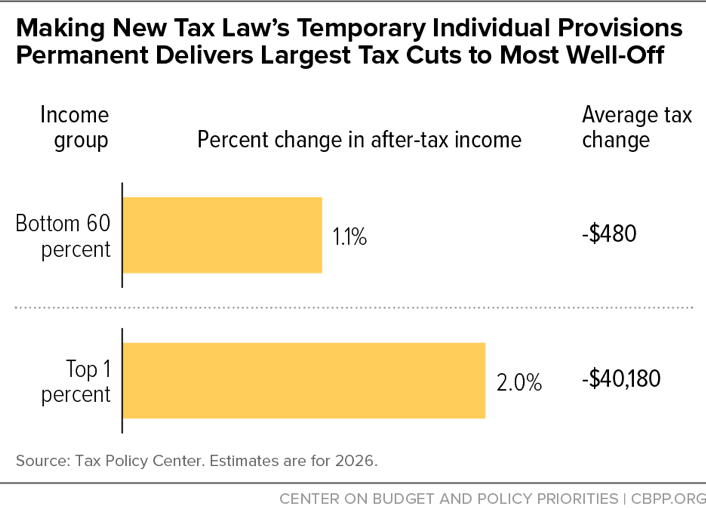

[11] TPC Table T18-0133. See: Marr and Duke, 2018.

[12] Chuck Marr et al., “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” CBPP, updated October 1, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/eitc-and-child-tax-credit-promote-work-reduce-poverty-and-support-childrens.

[13] Jennifer Beltrán, “Working-Family Tax Credits Lifted 8.9 Million People Out of Poverty in 2017,” CBPP, January 15, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/working-family-tax-credits-lifted-89-million-people-out-of-poverty-in-2017.

[14] Chuck Marr et al., “Strengthening the EITC for Childless Workers Would Promote Work and Reduce Poverty,” CBPP, April 11, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/strengthening-the-eitc-for-childless-workers-would-promote-work-and-reduce.

[15] The Hill Staff, “How the Trump tax law passed: The final stretch,” The Hill, September 30, 2018, https://thehill.com/policy/finance/409042-how-the-trump-tax-law-passed-the-final-stretch.

[16] Chye-Ching Huang, “Trump Favors Larger Corporate Tax Cuts Over More Help for Children in Low-Income Working Families,” CBPP, November 30, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/trump-favors-larger-corporate-tax-cuts-over-more-help-for-children-in-low-income-working.

[17] Marr, “Republicans Chose Corporate Shareholders Over Working Families.”

[18] Chye-Ching Huang, “Obscure Provision Tilts Senate Tax Bill Even More to Corporations,” CBPP, November 22, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/obscure-provision-tilts-senate-tax-bill-even-more-to-corporations.

[19] Rebecca M. Kysar, “Critiquing (and Repairing) the New International Tax Regime,” Yale Law Journal, October 25, 2018, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/critiquing-and-repairing-the-new-international-tax-regime.

[20] Chye-Ching Huang, “Fundamentally Flawed 2017 Tax Law Largely Leaves Low- and Moderate-Income Americans Behind,” CBPP, February 27, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/federal-tax/fundamentally-flawed-2017-tax-law-largely-leaves-low-and-moderate-income-americans.

[21] Committee on Ways and Means, “House Democrats Introduce Tax Package to Support Middle-Class Americans & Working Families,” press release, February 2, 2017, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/house-democrats-introduce-tax-package-support-middle-class-americans.

[22] Similarly, any “technical corrections” to fix mistakes in the 2017 tax law should not move unless the package address the law’s much bigger mistake of leaving low-income workers and families largely behind. For example, former Ways and Means Chairman Brady proposed last year a technical corrections package that would have helped restaurant and retail owners but do nothing directly for their workers. No technical corrections package that delivers a valuable fix to business owners or other high-income filers should be passed unless it also makes progress for workers and children. Chuck Marr, “House GOP Tax Fix for Restaurant, Retail Owners Leaves Out Millions of Their Workers,” CBPP, December 6, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-gop-tax-fix-for-restaurant-retail-owners-leaves-out-millions-of-their-workers.