BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said this week that the Trump Administration would like to “make the middle-class tax cuts permanent,” presumably referring to the 2017 tax law’s individual tax provisions, most of which are set to expire after 2025. But they’re not “middle-class tax cuts”: extending them, as many Republican lawmakers also favor, would raise after-tax incomes by more than twice as much (in percentage terms) for the top 1 percent of households as the bottom 60 percent, we estimate based on Tax Policy Center data. Extending them also would double down on the law’s three core flaws, providing another tax bill that’s skewed to the wealthy, fiscally irresponsible, and encourages rampant tax gaming and avoidance:

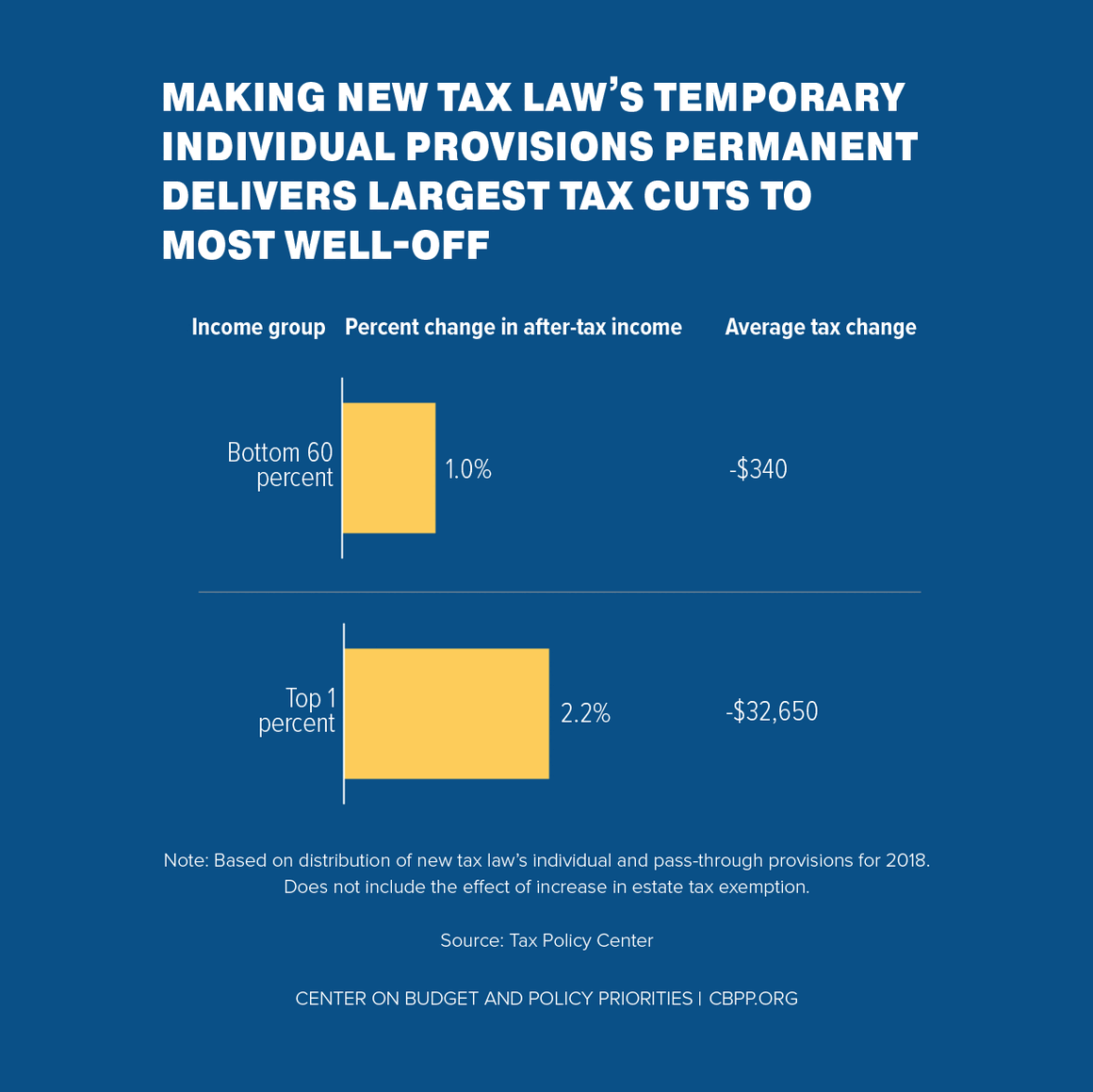

- It would most benefit wealthy households. U.S. income has shifted from households at the bottom and middle to those at the top in recent decades, as wages have been close to stagnant for many working families while income has risen sharply at the top. The 2017 tax law increases income inequality by delivering far larger tax cuts to the wealthy than to the bottom or middle. Making its individual tax provisions permanent would similarly increase income inequality after 2025, per this chart:

Extending the provisions would also violate Secretary Mnuchin’s promise soon after candidate Trump’s 2016 victory that “[t]here will be no absolute tax cut for the upper class” in a tax bill by delivering roughly $33,000 in annual tax cuts to the top 1 percent after 2025.

- It would add to deficits, compounding the nation’s fiscal challenges. The 2017 tax law costs an estimated $1.9 trillion over ten years, leaving the nation less prepared to address the retirement and health needs arising from the baby-boom generation’s retirement as well as other national needs that will require more revenue, not less. Making the individual tax provisions permanent would cost another $245 billion in revenues in 2027 alone, the Congressional Budget Office estimates. Making other parts of the tax law permanent, such as the “expensing” tax break for business investments in things such as equipment, would add even more to this cost.

- It would promote and prolong opportunities for tax gaming. The 2017 tax law created a 20 percent deduction for certain pass-through income — income that the owners of businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships report on their individual tax returns, which previously was taxed at the same individual tax rates as business owners’ other ordinary income. This creates so many opportunities for wealthy filers to reclassify their salaries as pass-through profits to qualify for the deduction that New York University Law School Professor David Kamin has called it “one of the worst provisions that’s been added into the tax code in the last several decades.” Making it permanent would further encourage high-income taxpayers to use complex tax avoidance schemes to lower their taxes.

Instead of doubling down, policymakers should set a new course and deliver true tax reform that avoids the 2017 law’s regressivity by benefiting low- and moderate-income working people far more, raises revenue to meet national needs, and improves economic efficiency by strengthening the integrity of the tax code.