BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The final Republican tax bill, which Republicans are rushing to pass this week, will ultimately raise taxes on many lower- and middle-income households and leave 13 million more people uninsured, to pay for permanent tax cuts for profitable corporations — the opposite of their claim that the bill will “strengthen the middle class.”

During the tax debate, Republicans blamed their choices on “the absurd rules of the Senate,” as White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney asserted. But that doesn’t make sense. The rules don’t force Republicans to write the bill as they did. They chose to do so — and to prioritize permanent deep corporate tax cuts above all other concerns.

They chose, for example, to use a special legislative process (“reconciliation”) so the bill could pass the Senate with a bare majority — and no Democratic votes — rather than the 60 votes that most legislation requires. They also chose to set up the reconciliation process so that the tax bill could add $1.5 trillion to deficits over the first decade, 2018 to 2027.

Because Senate reconciliation rules prohibit the bill from adding to deficits after 2027, Republican leaders then faced another choice: set the entire bill to expire by the end of the decade, so there were no costs after 2027; revise it so that it pays for itself after ten years; or make certain priority tax cuts permanent and pay for them with other permanent measures that raise revenues or reduce program spending, while letting lower-priority tax cuts expire. First in the Senate bill, and now in the final bill, they chose the last approach. And they centered the bill around permanent corporate rate cuts and other tax cuts for multinationals, raising taxes on low- and moderate-income households to pay for it.

- Permanent corporate tax cuts. From start to finish, the top GOP tax priority has been to cut the corporate tax dramatically, giving wealthy shareholders a windfall. The final bill cuts the corporate tax rate to 21 percent from 35, costing more than $1.3 trillion over ten years. Another, less-noticed provision would permanently set an even lower tax rate for U.S.-based multinationals’ foreign profits by adopting a “territorial” tax system, which would encourage firms to shift profits and investment offshore. As Senate Republican Ron Johnson said, “With a territorial system, there will be a real incentive to keep manufacturing overseas.” Yet Senate Republican leaders made this tax advantage for foreign profits one of their top priorities, along with lower corporate taxes generally. And the bill falls far short of containing enough corporate provisions that “broaden the base” and raise revenues to cover the cost of its deep, permanent corporate tax cuts. In fact, the main corporate revenue-raising provision is temporary and rewards multinationals that in the past shifted massive profits abroad to avoid U.S. tax.

- Permanent tax increase for lower- and middle-income households. Following the Senate bill’s lead, Republican lawmakers who negotiated the final bill set all of its tax cuts for individuals to expire after 2025 and all of its revenue-raising measures to expire except one: a slower inflation measure (the chained Consumer Price Index) for adjusting tax brackets and certain tax provisions each year to account for inflation. This permanent change would cause these key tax parameters to grow more slowly than under the current inflation measure — pushing many taxpayers, including many middle-income taxpayers, into higher tax brackets than otherwise. It would also raise taxes on low-wage workers by slowing the rate at which the Earned Income Tax Credit grows with inflation. This measure would raise taxes on households at all income levels, amounting to a $32 billion tax increase in 2027, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates.

- Millions more uninsured. To help pay for permanent corporate tax cuts, Republicans included a provision repealing the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate (i.e., the requirement that most people get health coverage or pay a penalty). That would raise the number of uninsured Americans by 13 million by 2027, according to Congressional Budget Office estimates. It also would raise premiums in the individual insurance market by an average of 10 percent. All of the savings — $53 billion in 2027 — would come because fewer people would be insured, resulting in somewhat lower spending on Medicaid and premium tax credits. The bill would use the savings to finance its permanent corporate rate cuts.

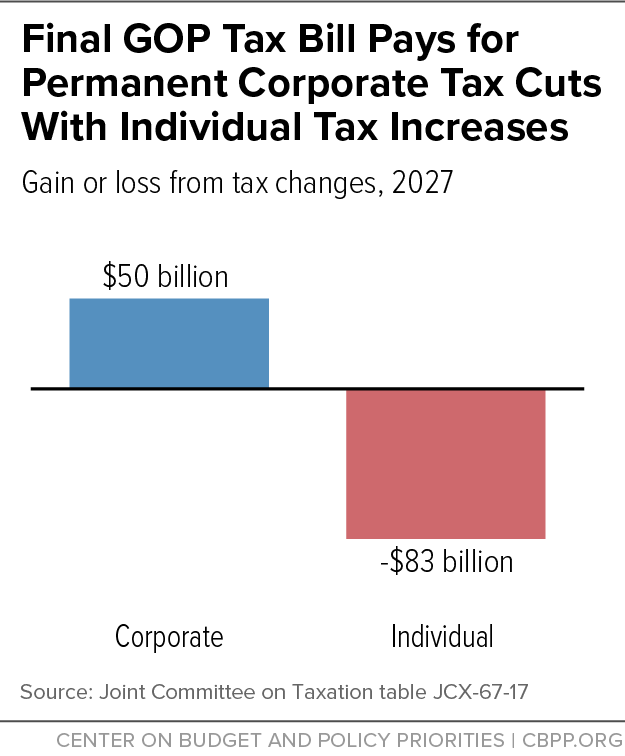

Overall, in 2027 — when only the corporate tax cuts, slower inflation measure, and individual mandate repeal would remain in place — the Senate bill would, on average, raise taxes for households by about $83 billion while cutting taxes for corporations by $50 billion. (See chart.)

So, contrary to Republican claims that byzantine Senate rules forced them to sunset the individual tax provisions, they were free to choose what to do in this bill at every stage, and they chose to write a final bill that favors corporations over individuals, and high-income households over middle-class and working-poor households.