New House Republican Tax Proposal Fails Fiscal Responsibility Test, While Favoring the Wealthiest

End Notes

[1] For an examination of the 2017 tax law’s shortcomings, see Chuck Marr, Brendan Duke, and Chye-Ching Huang, “New Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 14, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/new-tax-law-is-fundamentally-flawed-and-will-require-basic-restructuring.

[2] One of the other bills includes a “Universal Savings Account” (USA) proposal. For an analysis of USAs, see Brendan Duke, “’Universal Savings Account’ Proposal in New Republican Tax Bill Is Ill-Conceived,” CBPP, updated September 11, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/universal-savings-account-proposal-in-house-republican-tax-framework-is-ill.

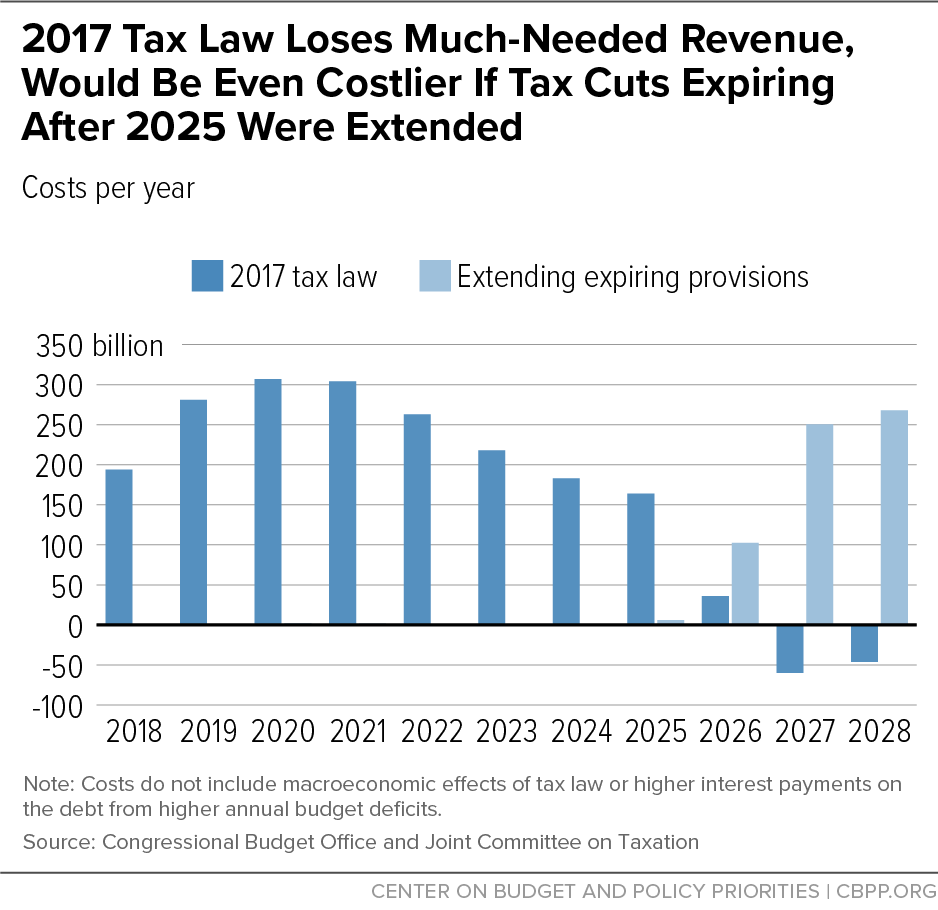

[3] When including the cost of the the tax plan’s other provisions not related to extending the 2017 tax law, the cost rises to $657 billion. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects of H.R. 6760,” September 12, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5136.

[4] Though much commentary, especially about the 2016 election, has focused on the “white working class,” the working class is diverse and working-class households of different races and ethnicities have secured only modest gains over the 1979-2015 period. See Chuck Marr, Brandon DeBot, and Emily Horton, “How Tax Reform Can Raise Working-Class Incomes,” CBPP, updated October 13, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/how-tax-reform-can-raise-working-class-incomes.

[5] Ibid.

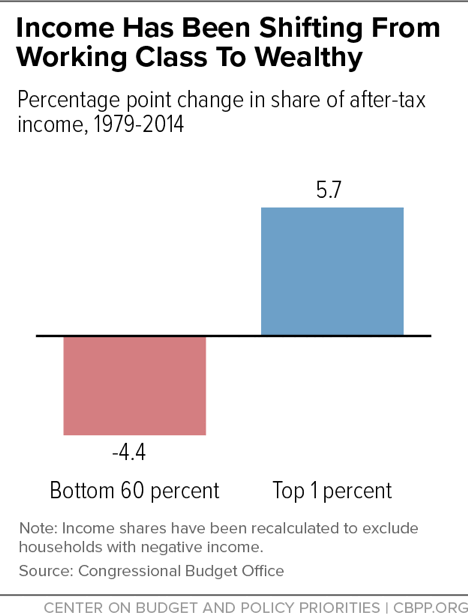

[6] The share of income going to the top 1 percent increased from 7.4 to 13.1 percent, while the share going to the bottom 60 percent fell from 36.3 to 31.9 percent. Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2014,” March 19, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53597. Income shares have been recalculated to exclude households with negative income.

[7] The 2017 tax law’s two permanent provisions other than the permanent corporate tax cuts were the repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, which results in health care cuts and higher premiums in the individual insurance market, and changing the inflation measure by which key tax parameters are adjusted for inflation, which will push households into higher tax brackets over time and reduce the value of the Earned Income Tax Credit. See Chuck Marr, “Republicans Chose Corporate Shareholders Over Working Families,” CBPP, December 19, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/republicans-chose-corporate-shareholders-over-working-families.

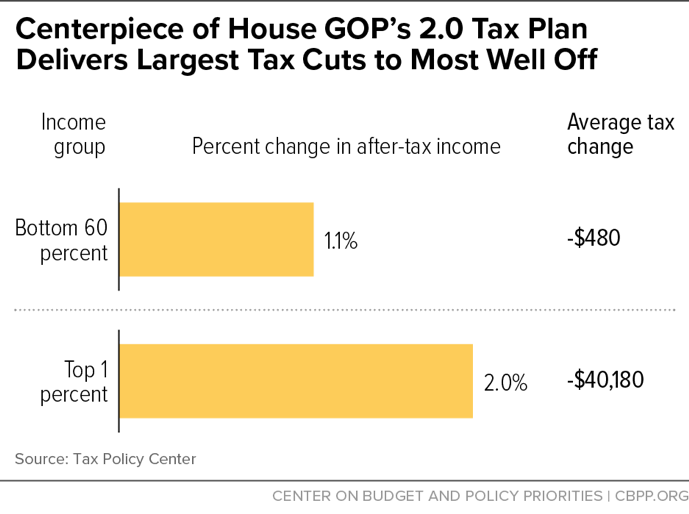

[8] Tax Policy Center Table T18-0133, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/hr-6760-protecting-family-and-small-business-tax-cuts-act-2018-introduced-1.

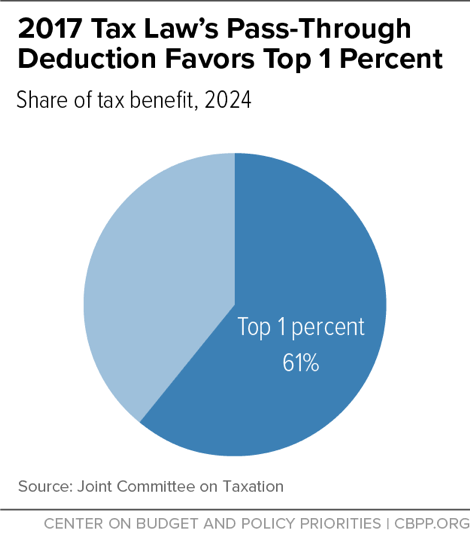

[9] Chuck Marr, “JCT Highlights Pass-Through Deduction’s Tilt Toward the Top,” CBPP, April 24, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/jct-highlights-pass-through-deductions-tilt-toward-the-top.

[10] Marr, Duke, and Huang 2018.

[11] To be sure, some provisions of the 2017 tax law raise taxes on high-income households, such as its limit on the deduction for state and local taxes. But the progressive provisions are overwhelmed by the regressive ones, resulting in a highly regressive law overall, as the Tax Policy Center analysis cited in the text shows.

[12] Christopher R. Tamborini, ChangHwan Kim, and Arthur Sakamoto, “Education and Lifetime Earnings in the United States,” Demography, 52 (4) (2015): 1383-1407.

[13] Chuck Marr, Brandon DeBot, and Chye-Ching Huang, “Eliminating Estate Tax on Inherited Wealth Would Increase Deficits and Inequality,” CBPP, updated April 13, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/eliminating-estate-tax-on-inherited-wealth-would-increase-deficits-and.

[14] CBPP, “2017 Tax Law’s Child Credit: A Token or Less-Than-Full Increase for 26 Million Kids in Working Families,” August 27, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/2017-tax-laws-child-credit-a-token-or-less-than-full-increase-for-26-million.

[15] Joel Friedman and Richard Kogan, “House GOP Budget Retains Tax Cuts for the Wealthy, Proposes Deep Program Cuts for Millions of Americans,” CBPP, June 28, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/house-gop-budget-retains-tax-cuts-for-the-wealthy-proposes-deep-program-cuts.

[16] For an analysis of the distributional effect of the entire 2017 tax law once financing is taken into account, see William Gale et al., “Effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: A Preliminary Analysis,” Tax Policy Center, June 13, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/effects-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-preliminary-analysis, p. 13.

[17] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects of H.R. 6760.”

[18] Jeffrey Rohaly et al., “Analysis of the Protecting Family and Small Business Tax Cuts Act of 2018,” Tax Policy Center, September 12, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/publication/155760/hr6760_wm_forpub_2.pdf.

[19] Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028.”

[20] Paul N. Van de Water, “Federal Spending and Revenues Will Need to Grow in Coming Years, Not Shrink,” CBPP, September 6, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/federal-spending-and-revenues-will-need-to-grow-in-coming-years-not-shrink.

[21] Howard Gleckman, “The Downmarketing of Tax Shelters,” TaxVox, January 18, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/downmarketing-tax-shelters.

[22] Matthew Smith et al., “Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century,” July 23, 2017, https://eml.berkeley.edu/~yagan/Capitalists.pdf.

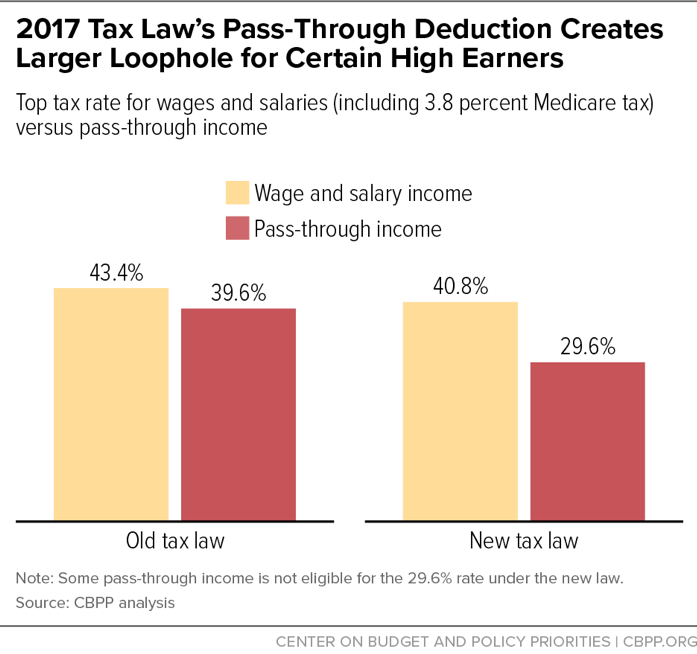

[23] Wage and salary income previously faced a top marginal tax rate of 43.4 percent (39.6 percent in ordinary income tax + 3.8 percent in Medicare taxes), while pass-through profits faced a top tax rate of 39.6 percent, a differential of 3.8 percentage points. Under the 2017 tax law, wage and salary income faces a top marginal tax rate of 40.8 percent (37 percent in ordinary income tax + 3.8 percent in Medicare taxes), while pass-through profits eligible for the deduction face a top rate of just 29.6 percent (37 percent x 80 percent because of the 20 percent deduction). The differential between the top rates on wage and salary income and pass-through profits eligible for the deduction thus is now 11.2 percent (40.8 percent versus 29.6 percent).