Federal policymakers face a major decision at the end of this month when the CARES Act’s significant boost in unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, which has provided a lifeline for millions of families, is scheduled to expire. To reduce hardship for families and pressures for states to reopen their economies prematurely, which would cost lives and likely delay an economic recovery, policymakers should provide robust assistance to individuals and state and local governments and continue it as long as it is needed.

Confronted by a pandemic-induced economic free-fall early this spring, the President and Congress quickly enacted several pieces of relief legislation with provisions to shore up household incomes. Those measures generally worked well, preventing poverty from spiking even as millions of workers lost their jobs and keeping household consumption — and hence the economy — from sinking even further. Yet the downturn has inflicted severe, widespread hardship, as data on rising food insecurity, housing insecurity, and other hardships and the miles-long lines of cars outside food banks attest.

The President has repeatedly signaled that his preferred path forward starts with aggressive reopenings of local economies. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, anticipating a strong economic rebound, said at the end of May that he preferred the next relief package be “narrowly crafted, designed to help us where we are a month from now, not where we were three months ago.”[1] Senator McConnell has now called for significantly limiting the package in size and scope. Yet this approach makes a fundamental error by assuming that the public health restrictions imposed in response to the pandemic are at the root of the downturn and that the economy will recover strongly once they are lifted.

To the contrary, COVID-19’s recent resurgence in states that reopened prematurely shows the economy will almost certainly remain weak for many months and that a full recovery cannot occur until the virus is under control and people feel safe resuming economic activity. These reopenings have failed as a strategy to bolster household and state finances, and this strategy cannot justify a federal retreat on robust fiscal help for families and states. Instead, policymakers should act now to build on the success of efforts to date to alleviate hardship and bolster the economy.

This paper, divided in to five sections, reaches the following conclusions:

Legislation responding to the pandemic has softened the recession’s blow to low- and moderate-income households and the economy, research shows. UI benefit and eligibility expansions and one-time stimulus payments enabled low- and moderate-income families to maintain their spending, cushioning the blow to overall spending and the economy. Personal incomes were actually higher in April and May than in February, and poverty rates fell by about 2 percentage points over that period, although this partly reflected the one-time infusion from the stimulus payments. The assistance also prevented the income and poverty gaps between Black and Latino households and white households from growing. Overall, by getting resources to households that spent them, federal assistance prevented even deeper job losses and an even sharper decline in the economy. But the federal supplement to weekly unemployment benefits, which has played a large role in keeping things from getting worse, is slated to expire in just a few weeks.

Yet many households are suffering hardship, highlighting the shortcomings in measures enacted to date and the need to do more rather than to retrench prematurely. Real-time data on food insecurity and adverse mental health conditions from weekly Census Bureau surveys show tremendous unmet need. Roughly 1 in 5 renters are behind in their rent payments, potentially setting up a wave of evictions once various moratoriums on evictions end, and food insecurity has risen sharply. The CARES Act excluded important types of assistance that could have helped address food insecurity while also aiding the economy, such as an increase in the maximum SNAP (food stamp) benefit akin to that enacted during the Great Recession.

Efforts to reopen states before the virus is under control have proven dangerous and ineffective. Infections and hospitalizations have surged in various states that pushed ahead before meeting the basic federal criteria for reopening. Prematurely reopening also has failed in strictly economic terms, by assuming incorrectly that people would resume their normal spending patterns when their state reopened even if the pandemic remained uncontrolled. Research shows that economic activity collapsed earlier this year primarily because people curbed their activities to avoid getting sick or infecting others, not because of state stay-at-home restrictions, and lifting those restrictions reversed only a modest part of the pandemic-induced decline in economic activity. Premature reopening will not encourage enough activity to restore the economy, but apparently it does encourage enough activity to spread the virus. This means that pushing states to reopen their economies prematurely is no substitute for assisting individuals and cash-strapped state and local governments.

An inadequate federal response would hinder efforts to control the pandemic and hurt households and the economy. Despite some positive economic news, the path of the recession remains very uncertain, driven by a public health crisis that is not close to being under control. Mainstream forecasts suggest that without further fiscal stimulus, the economy will remain weak for an extended period. Indeed, allowing the CARES Act’s expansion of UI benefits to expire without a replacement would cost an estimated 2 million jobs over the next year, according to former Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) Chair Jason Furman.[2] Further, state budgets have yet to feel the recession’s full impact; states’ massive shortfalls will force deep cuts and layoffs to comply with states’ balanced-budget requirements.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has emphasized that the costs of failing to enact further fiscal stimulus would be large and long-lasting: “If we let people be out of work for long periods of time, if we let businesses fail unnecessarily, waves of them, there’ll be longer-term damage to the economy.”[3] Failure to protect families and the economy would also widen the nation’s glaring racial inequities, as the pandemic’s health and economic impacts are disproportionately affecting people of color.

Strong fiscal stimulus thus is urgently needed. Federal policymakers should enact further, strong stimulus measures, including income supports for struggling individuals and families and robust fiscal relief for states, as well as stronger public health measures to contain the spread of the virus. The House took a strong step in this direction when it passed the Heroes Act in May.

As policymakers negotiate the next fiscal package, specific policies that merit adoption include:

- Extending the current UI eligibility expansions, providing a substantial federally funded benefit increase above pre-pandemic levels (without the CARES Act, benefits would have averaged only about $320 per week in May), and providing additional weeks of benefits to give unemployed workers more time to find a job while unemployment remains high.

- Helping those struggling the most by: boosting SNAP benefits for all participants by increasing the maximum benefit amount, which serves as the program’s benefit standard; increasing funding for rental assistance and homelessness services and prevention; providing emergency grants to states to provide targeted help to families falling through the cracks; and expanding (for tax year 2020) the Earned Income Tax Credit for workers without minor children at home and the Child Tax Credit for children in families with little or no income.

- Providing robust fiscal relief that meets rising needs for Medicaid and helps states and localities avert deep cuts in education, transportation, and services for struggling residents.

- Reversing the CARES Act provision that excluded many families from relief measures because they include one or more immigrant members who lack a Social Security number.

- Providing further resources for public health measures to arrest the relentless spread of the virus.

The President and Congress have enacted several pieces of relief legislation so far to address the current economic and health crisis. The largest of these measures, the CARES Act, included sound policies — such as a sizeable expansion of unemployment benefits and direct stimulus payments — that delivered resources to low- and moderate-income people facing job losses and other financial hardship as a result of the pandemic and recession. A substantial body of new research shows that these provisions have protected millions of people from even more severe financial stress, cushioning the blow to consumer spending and the economy overall.[4] To be sure, the CARES Act had important shortcomings (see discussion below),[5] and households and the economy still face daunting challenges; the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the unemployment rate will remain above 10 percent through the end of the year and that the unemployment rate and real gross domestic product (GDP) won’t return to their levels in CBO’s pre-pandemic (January 2020) projections until late in the decade. But the situation would be far more severe without the CARES Act and the other measures enacted to date.

CARES Act relief quickly reached millions of households in need. For example, though a deluge of claims initially overwhelmed state UI systems, by the week ending June 13 some 31.5 million unemployed workers were claiming UI benefits, which were more generous than the workers would otherwise have received, including 11 million people who would have received no UI benefits at all..[6] Similarly, the IRS delivered over 150 million stimulus payments by June 3 despite years of ill-advised funding cuts that have left that agency understaffed and technologically out of date.[7]

Together with existing safety net programs such as the regular UI program, Medicaid, and SNAP, the CARES Act and its predecessor, the Families First Act, shored up low- and moderate-income families’ incomes, preventing a large increase in poverty and maintaining many families’ ability to spend on necessities.

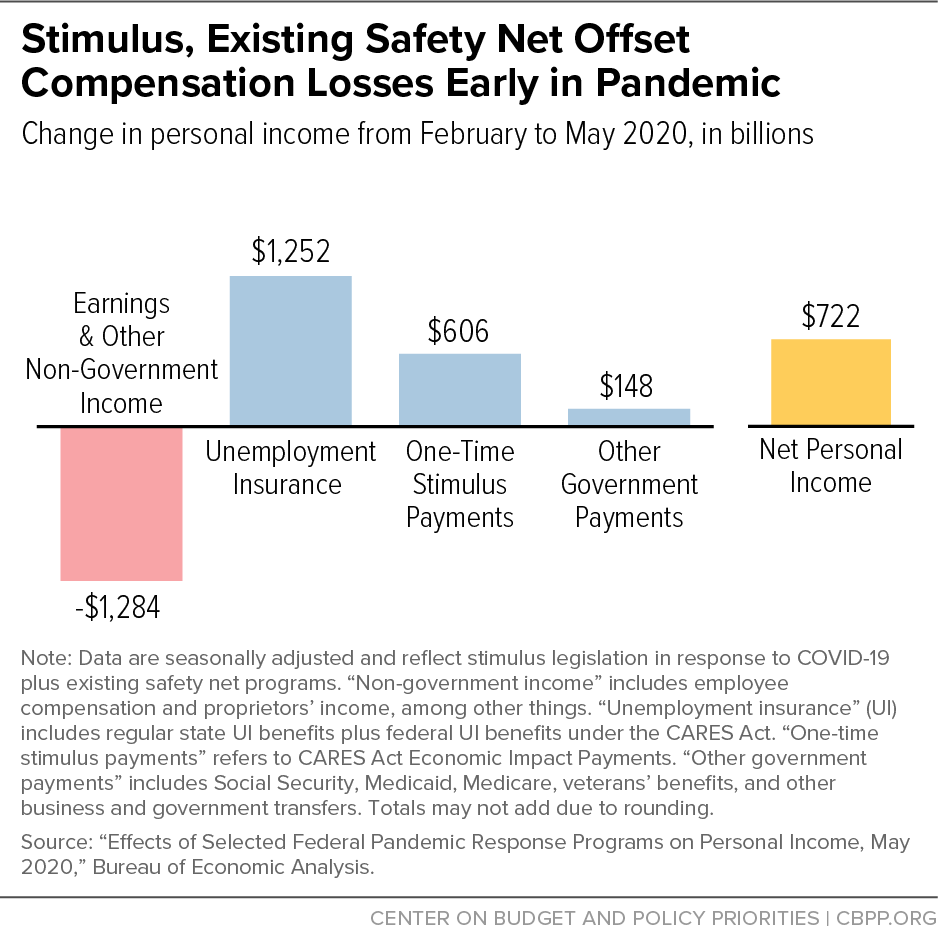

Job losses — 21 million jobs lost in April alone, compared to 8 million jobs lost in the entire Great Recession — and reductions in work hours caused earnings from employment (wages, salaries, and other compensation) to plummet in April and May, with jobs and earnings losses concentrated among low-paid workers.[8] But government transfers more than offset lost employment earnings in those months. This meant that individuals’ disposable incomes were actually higher in the aggregate in April and May than in February, though that was in part due to the CARES Act stimulus payments, which were one time only.[9] (See Figure 1.)

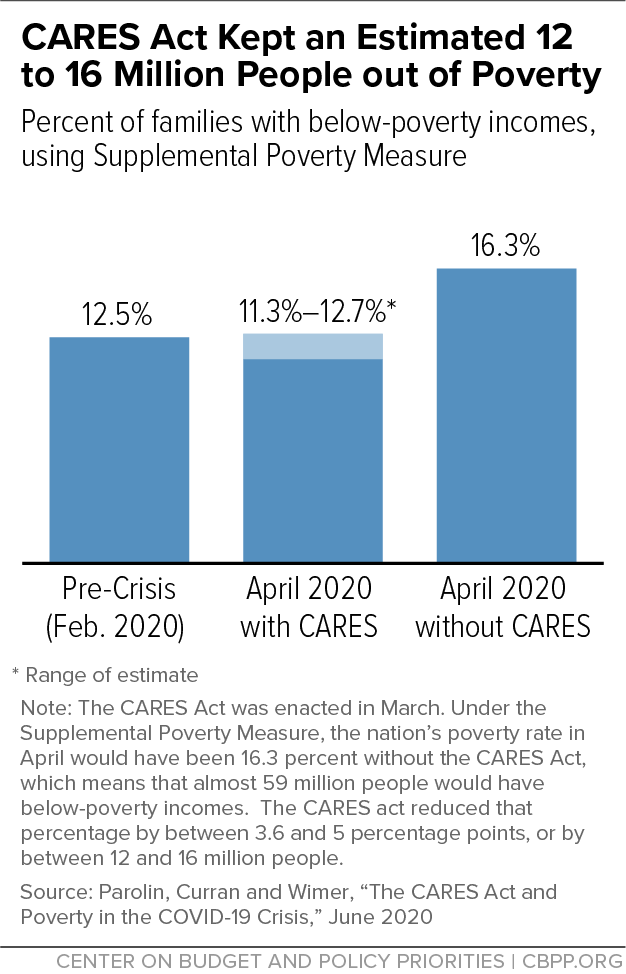

The combination of the existing safety net and the relief measures enacted to date also prevented poverty rates from rising in the early stages of the recession despite the enormous job and earnings losses among low-income households, new studies estimate. (These studies use the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which accounts for government transfers and taxes, unlike the “official” poverty measure.) One study estimated that the poverty rate actually fell by about 2 percentage points in April and May due to the CARES Act’s UI expansions and stimulus payments as well as existing safety net programs.[10] Another study, by Columbia University researchers, estimated that the CARES Act measures by themselves will keep 12 to 16 million people from falling below the poverty line in 2020.[11] (See Figure 2.)

Black and Latino workers have faced some of the worst employment and earnings losses in the recession, so CARES Act policies were particularly important to them and their families, averting especially large spikes in Black and Latino poverty. Because most of the job losses in the first two months of the downturn occurred in industries with low average wages, the biggest earnings losses hit workers who already faced high poverty rates and high barriers to economic opportunity, including many Latino and Black workers, workers without a bachelor’s degree, and immigrants.[12] But the CARES Act, the Columbia researchers estimate, largely filled in these earnings losses on average — though not necessarily before families experienced days or weeks of anxiety or hardship. As a result, the recession appears — so far — not to have aggravated the already large poverty disparities between people of color and white individuals.[13]

Because the CARES Act prevented low-income households’ incomes from falling steeply early in the recession, many households did not have to cut their spending drastically at that time. At the end of May, the lowest-income quarter of households continued to spend at nearly the same levels as before the crisis, and by mid-June, low-income consumer spending was down only 2.8 percent, credit card data show.[14] Anonymized data from a large bank also show, “Spending plunged for all households at the onset of the pandemic. After government stimulus, poorer households had more rapid spending and savings growth than richer households.”[15] Much of the CARES Act’s one-time stimulus payments was spent rapidly, with the largest responses among low-income households and the largest spending increases going for food, non-durables (such as other groceries), and rent and bill payments, research indicates.[16]

The CARES Act also alleviated hardship. When families with a worker who lost a job started receiving UI benefits, their rate of food insecurity fell, longitudinal survey data show; they were also less likely to report concerns about paying for basic expenses (food, housing, utility bills, debt, and medical costs), or worries about meeting basic needs in the next month.[17] Similarly, UI applicants reported lower rates of food insecurity and problems paying utility bills after receiving stimulus payments, although those payments did not reduce recipients’ worries about meeting basic needs in the next month,[18] perhaps due to their one-time nature.

Getting resources quickly to financially struggling households so they can continue buying necessities is also the most cost-effective form of economic stimulus. That’s because it prevents demand for goods and services across the economy from falling more deeply and so keeps other people employed and businesses afloat.[19] At its peak impact, the CARES Act will reduce the unemployment rate by roughly 0.9 to 1.7 percentage points — or by 1.5 to 2.7 million workers — according to Moody’s Analytics.[20] Likewise, Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi concludes that without the CARES Act, GDP would have plummeted by nearly 10 percent in the second quarter of 2020 alone (over 40 percent annualized) — “a complete wipeout.”[21] Some evidence suggests that states with more generous UI benefits have had milder economic declines and faster recoveries in jobs.[22]

While the federal response to the crisis has helped millions of households, the recession has inflicted widespread and severe hardship. It has, for example, made it substantially more difficult for many hard-pressed households to afford adequate food.

- Food insecurity rates have nearly tripled from pre-crisis levels, with almost a quarter of families reporting their food “just didn’t last” and they did not have money to buy more.[23]

- Nearly 1 in 5 (18.8 percent) of households with children surveyed in the week of June 25-30 reported that the children sometimes or often hadn’t eaten enough in the past week because their families couldn’t afford adequate food. That’s a substantial rise from December 2018, when only about 3 percent of adults in households with children reported that their children were sometimes or often not eating enough.[24]

- Feeding America, the national organization serving food banks and emergency feeding outlets, has reported a 70 percent increase in the number of people seeking food since the pandemic began.[25]

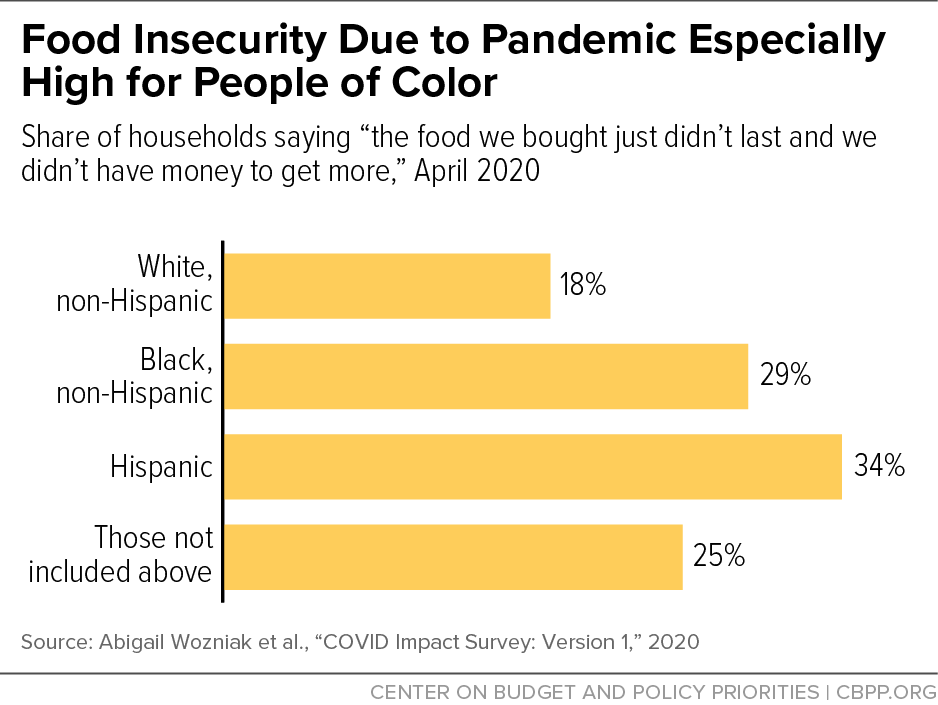

- The spike in food insecurity has been particularly acute among people of color. In national survey responses from late April, 34 percent of Hispanic households and 29 percent of Black households said the food they bought didn’t last and they didn’t have enough money to obtain more, well above the 18 percent rate for white households.[26] (See Figure 3.)

- “Adverse mental health conditions also have worsened,” one study found, “with rates of depression and anxiety doubling over pre-COVID levels.[27]

- In the week ending June 30, an estimated 14.2 million adults who rented their homes — fully 1 in 5 renters — were behind on rent, with the rate being nearly twice as high for renters with children as for those without children.[28] While eviction moratoriums protect many households for the moment, renters who cannot afford to pay rent continue to accrue debt, and there is growing risk this may cause a wave of evictions once the moratoriums end.

- The share of renters behind on rent is even higher for Black (29 percent) and Latino renters (26 percent), deepening racial and ethnic disparities to which government housing policies of earlier decades contributed substantially.[29] And Black and Latino households are more likely to be renters and have lower incomes and fewer assets, putting them at higher risk of being unable to pay their rent during a crisis.

Such hardship likely reflects not only the extent of the economic decline but also the difficulty of getting CARES Act support to millions of eligible households, as well as important gaps and shortcomings in the Act. For example, while the IRS delivered the vast majority of the stimulus payments directly to households, an estimated 12 million adults and children in households that do not file federal income tax returns will have to submit a form to the IRS to receive the payments. Aggressive outreach will be needed to ensure that payments reach this group, which tends to have lower incomes and includes many people who faced high barriers to economic opportunity even before the crisis. These non-filers are disproportionately Black and Latino, tend to have less education, and include many people who lack secure housing.[30]

In addition, the CARES Act lacked important types of assistance that could have further supported households and the economy.[31] These include provisions to expand health insurance coverage or pay for COVID-19-related treatment for the uninsured and an increase in the maximum SNAP benefit level to help families afford sufficient food, which would have tempered the increase in food insecurity and helped shore up consumer spending.[32] The CARES Act also lacked other measures to meet the extraordinary needs of the moment, including an emergency fund modeled after the successful TANF Emergency Fund that was in place during the Great Recession, or robust help for people facing housing crises. It also didn’t fill various holes in the U.S. safety net; for example, adults not raising children are largely or entirely excluded from the EITC and other programs. And some CARES Act provisions themselves have gaps, such as the exclusion from stimulus payments of all members of immigrant and mixed-status families unless every member has a Social Security number; this sweeping bar has caused millions of people who have Social Security numbers to lose out.[33]

Policymakers should now benefit from the experience of the CARES Act and enact further, strong measures that replicate the Act’s successes at shoring up incomes and the broader economy while addressing its key shortcomings. Unfortunately, some policymakers have started to take states and the nation down a different path, which has quickly proved dangerous, as the next section explains.

The President and some members of Congress have called for states and local governments to lift various restrictions aimed at limiting the virus’ spread and aggressively reopen, with President Trump saying, “We’re opening and we’re opening with a bang.”[34] This, they argue, would help spark a rapid (or “v-shaped”) recovery. The President stated on June 18 that “a ‘V’ is the thing we were shooting for and it looks like that’s what we’ve got.”[35]

Some policymakers have suggested this route would allow for a marked reduction of fiscal support to households and largely close the massive state and local budget shortfalls that threaten extensive cuts to jobs and services.[36] According to some news reports, the White House has resisted robust fiscal relief for state and local governments in part to prod those governments to open their economies more rapidly and to a greater degree.[37] The White House has continued to push this approach of reopening states even as it has become clear that it has failed on both health and economic grounds.[38]

A number of states tested that approach beginning in May and June, encouraging businesses to reopen and people to return to restaurants, bars, and other social settings even though the virus was not controlled and most of the states had not yet met basic federal criteria for reopening.[39] The subsequent surge in cases and hospitalizations in many of these areas shows that premature reopenings increase the pandemic’s toll on residents’ health.[40] Thirty-seven states and the U.S. Virgin Islands have reported an increase in cases per capita in the last two weeks.[41] Initial evidence suggests that Black and Latino people will be harmed disproportionately from the recent increases, as they were earlier in the pandemic.[42]

Even strictly in terms of economic activity, the strategy of premature reopenings failed because it incorrectly assumed that people would return to their normal spending patterns when their state reopens, even if the pandemic is not yet controlled.

Only a small part of the collapse in economic activity at the pandemic’s onset was due to official restrictions, a number of studies have shown; a much larger part was due to people curbing their activities to avoid getting sick or infecting others.[43] For example, University of Chicago economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson found that legal shutdown orders were responsible for only about 11 percent of the reduction in commercial activity at the onset of the pandemic and that “individual choices were far more important and seem tied to fears of infection.”[44] As a result, “the recovery is limited not so much by [stay-at-home] policy per se as the reluctance of individuals to engage in economic activity that requires interacting with others.” Similarly, economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues at Opportunity Insights found that spending by high-income households fell sharply well before formal shutdown orders were implemented; they concluded that that “[h]igh-income households cut spending primarily because of health concerns rather than a loss of income or purchasing power.”[45]

While fewer studies have been published so far on the effect of the recent reopenings, they similarly find that lifting official restrictions reverses only a small part of the pandemic-induced decline in economic activity. States and counties that started rescinding their shutdown orders saw only modest increases in economic activity, Goolsbee and Svenson found — increases comparable to the declines in activity when they adopted the shutdown orders. Other researchers found consumer spending patterns in the neighboring states of Minnesota and Wisconsin were nearly identical from February through May even though they began reopening several weeks apart.[46] In addition, real-time data on activity such as customer traffic and restaurant table bookings show that reopening retail stores and restaurants has not restored activity to anywhere near pre-pandemic levels.[47] And a recent Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis survey of businesses found that “respondents cited lack of customer demand as a top factor restraining their ability to operate at pre-crisis levels.” The survey also found, “Firms continue to report declines in demand, while overall employment has increased. This suggests the rate of businesses reopening may be faster than the rate of customers coming back to stores.”[48]

It has become clear that premature reopening is simply not a sustainable strategy: though it will not encourage people to engage in enough activity to return the economy to pre-pandemic levels, it evidently does encourage enough activity to cause a resurgence of the virus. That, in turn, sets back the recovery, both because it leads even reluctant policymakers to reinstate restrictions and because it affects consumer behavior directly.

Many governors, faced with surging case counts and the risk of exceeding hospital or intensive care unit capacity, are pausing their reopenings or reinstating restrictions; indeed, over half of the U.S. population now lives in a state that has begun reimposing stricter policies or placed reopening plans on hold.[49] As a result, “Millions of workers are suffering from economic whiplash, thinking they were finally returning to work — only to be sent home again as cases spike,” the Washington Post reports.[50]

Meanwhile, real-time data from mapping services, mobile phones, and business scheduling services show slowdowns or declines in activities such as retail, recreation, and business visits and in the numbers of businesses open and employees working.[51] (Due to normal reporting lags, official employment and GDP data are not yet available for the recent period in which the virus has been surging and some states have started reclosing.) Consistent with data showing that consumers reduced their activity early in the pandemic far more because of health concerns than official legal restrictions, these new data again show activity beginning to slow even before authorities started reimposing stricter public health policies.[52]

Economists across the political spectrum agree that restarting the economy on a sound footing requires first getting the virus under control, including retaining social distancing measures as long as necessary. As a recent statement from the bipartisan Economic Strategy Group (with signatories including Glenn Hubbard, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, and Ed Lazear, all of whom served in Republican administrations) explains:

Saving lives and saving the economy are not in conflict right now; we will hasten the return to robust economic activity by taking steps to stem the spread of the virus and save lives.[53]

Similarly, Federal Reserve Chairman Powell has said, “The path forward for the economy is extraordinarily uncertain and will depend in large part on our success in containing the virus. A full recovery is unlikely to occur until people are confident that it’s safe to engage in a broad range of activities.[54]

Moreover, it is increasingly clear that some segments of the economy (such as bars and in-person restaurant dining) may face added delays and not reopen safely for some time, or even until an effective vaccine or therapeutic is widely deployed.[55] And while some localities or states may be able to reopen schools if they can first reduce local infection rates to low levels and implement robust safety protocols, this will increase the risk of transmission, making it even more important that non-essential businesses with high risks of transmission remain closed in order to limit the spread of the virus.[56] To reduce both hardship for families and pressure for premature reopenings that would cost lives and prevent a sustainable economic recovery, the federal government should provide robust assistance to individuals and state and local governments and continue it as long as needed.

Some proponents of rapid reopening argue it would render unnecessary any further federal fiscal aid to states and localities and allow a substantial reduction in the federal support now going to households through expanded UI benefits and other measures. But in reality, until the pandemic is under control and full reopening becomes possible, further federal aid for states and support for households will be critical to averting unnecessary hardship and preventing the recession from being deeper and longer — and thus more damaging over the long run — than would otherwise occur.

While some positive economic news (such as the addition of 4.8 million jobs in June) suggests we are moving away from the lowest point of the recession, the situation remains dire. The unemployment rate was still 11.1 percent overall in June and especially high for Black (15.4 percent), Hispanic (14.5 percent) and Asian (13.8 percent) workers. The broadest measure of unemployment and underemployment was 18 percent in June, higher than in any pre-pandemic month on record. Further, these latest figures are based on data from mid-June and do not capture some state reclosures after failed attempts at reopening; some forecasters who update their projections more frequently have responded to the virus’ recent resurgence by downgrading their estimates of GDP and consumer spending for the third quarter of 2020.[57]

Indeed, mainstream forecasts suggest that without substantial further federal stimulus, the economy will remain weak for a considerable time. CBO, for example, projects that with no further fiscal stimulus, the unemployment rate will average 8.4 percent in 2021 and still be at 7.6 percent at the end of that year. CBO also projects that real GDP over 2020-2021 will be 6.7 percent below its pre-pandemic forecast.[58]

In short, states, localities, households, and the economy continue to face substantial need that the reopening strategy has not relieved. States face historic budget shortfalls, which CBPP estimates will total $555 billion over three state fiscal years, due to the pandemic and economic fallout.[59] Localities, U.S. territories, and tribal governments also face large shortfalls. Absent further fiscal relief, their balanced-budget requirements will force states and localities to cut services and jobs deeply. In April and May alone, states and localities furloughed or laid off 1.5 million workers,[60] about twice as many as in the Great Recession. Nearly half were school employees;[61] layoffs also affected essential health care workers. Without more federal assistance, states and localities will be forced to make even deeper cuts as they write (or rewrite) their budgets for the new fiscal year (which began on July 1 in most states) and as states exhaust their “rainy day funds.”

Needless to say, the problematic reopening strategy has not removed the threat of a looming state fiscal crisis. Instead, as the Washington Post reports,[62] “A surge in coronavirus cases threatens to arrest the country’s early economic recovery, leaving Texas and other hard-hit states staring down another round of massive revenue losses that could imperil their budgets. . . . [This] may offer a fresh warning sign that even the strongest economies are vulnerable when an uncontrolled pandemic results in prolonged disruption.”

Not continuing or drastically curtailing the CARES Act’s UI expansions, which expire July 31 for the benefit boost and December 31 for the added weeks of benefits and eligibility expansion, would also weaken the economy. Former CEA Chair Jason Furman estimates that letting those measures expire without a replacement would “subtract 2.5 percent of GDP on average in the second half of this year, costing an average of 2 million jobs over the next year, and raising the unemployment rate by up to 1.2 percentage points. . . . These costs would not just be borne by the currently unemployed who would be losing benefits but more broadly across the economy.”[63] Other analysts agree that allowing the CARES Act measures to lapse without replacements would have a significant, negative impact on jobs and GDP.[64]

Some policymakers have expressed concern that the CARES Act’s UI measures may be too generous, causing laid-off workers to choose to remain unemployed. In reality, as long as the virus remains uncontrolled, what is holding back employment is primarily the lack of jobs, not assistance to jobless families. As Furman recently testified:

For now . . . the constraint on jobs appears to be more that employers were not hiring than that employees were unwilling to take jobs. This is also true because of return-to-work rules in unemployment insurance and the fact that many unemployed individuals are not eligible for unemployment insurance even under the broader eligibility provided in the CARES act. New entrants, recent high school or college graduates, and those with no prior earnings all cannot collect unemployment insurance. Thus, there are many individuals ready to be hired regardless of the effect of unemployment insurance generosity.[65]

By making it much more difficult for jobless workers and their families to meet basic needs, letting UI benefit levels fall back to pre-pandemic levels would greatly increase the pressure on those workers to take any job available regardless of the health risks, the lack of safe jobs, and the fact that many families face other constraints, such as a lack of adequate child care. It also would increase the pressure on states to reopen rapidly even if the virus is not yet under control. (Some of the same policymakers who argue that UI benefits are too high also favor rapid reopening.) The contrary approach, of assisting unemployed workers and struggling families by bolstering UI and other parts of the safety net, would support the public health measures needed to control the virus and thereby help generate a sustainable economic recovery.

Assisting families facing financial hardship also prevents unnecessary damage to the economy, both now and over the long term; polices that do so are among the most effective at shoring up consumer demand and so can moderate the recession and boost the recovery. Additional dollars spent on UI, SNAP, and refundable tax credits go primarily to low- and moderate-income families that are likely to spend them quickly to make ends meet; this helps the businesses and workers that produce and sell the goods and services — in turn, helping them maintain their own spending and hiring. CBO and economists generally rate UI, SNAP, and refundable tax credits as among the most cost-effective forms of stimulus, estimating that each federal dollar spent on them generates more than $1 in increased demand across the economy when demand is weak. Fiscal relief for states and localities — including an increase in the federal share of Medicaid costs — also has high “bang-for-the-buck” because it helps them avoid cutting services, laying off workers, and raising taxes.[66]

As noted, the CARES Act provisions actually raised disposable incomes among low-income people in April and May despite large job losses and sharp drops in earnings and other compensation. But some of those provisions were one time only, and letting others expire without adequate replacement to offset lost incomes for tens of millions of people would likely lead to more poverty and food insecurity and poorer health outcomes. Without adequate UI and other assistance to cushion their incomes, and without safe jobs to return to, unemployed workers would likely cut their spending significantly, hurting other businesses and workers as well.[67]

The economic damage from inadequate fiscal stimulus would likely be long-lasting, as Federal Reserve Chairman Powell has emphasized.[68] Workers’ skills can erode while they are unemployed, and a weak job market can force people to take jobs that don’t fully use their skills, putting them on a worse job and earnings trajectory.[69] Moreover, the human impact can be considerable and lasting. Children who grow up in poverty risk long-run harm to their academic achievement, health, and adult earnings. Similarly, research finds that children whose parents lose a job are likelier to repeat a grade and have lower lifetime earnings and higher mortality later in life.[70] As in the Great Recession, state budget cuts may also fall heavily on areas such as education and infrastructure, holding back residents and the economy from thriving in the long run.

Failure to protect families and the economy from more damage would also widen the nation’s glaring racial inequities. The pandemic’s health and economic impacts are disproportionately affecting people with low incomes and people of color, who already faced systemic barriers to economic opportunity going into this crisis. Black people’s much higher death rates due to COVID-19 likely reflect, in part, structural inequities in health and its social determinants, such as access to safe housing and adequate nutrition.[71] Job and earnings losses in the pandemic are also hitting Black and Latino workers disproportionately; the immediate job losses were concentrated in low-paid service-sector jobs, which people of color, women, and immigrants are likelier to hold. These groups also disproportionately perform essential front-line jobs at increased risk to their health, such as transporting people and goods and producing and selling food.[72]

The CARES and Families First acts, while insufficient in key respects, delivered badly needed help to households that mitigated the pandemic’s economic fallout and reduced hardship in the initial months. Now, as Fed Chairman Powell has urged, “This is the time to use the great fiscal power of the United States to do what we can to support the economy and try to get through this with as little damage to the longer-run productive capacity of the economy as possible.”[73]

Policymakers should enact further, strong stimulus measures that include critical income supports for struggling individuals and families and robust fiscal relief for states, as well as stronger public health measures to contain the spread of the virus. Doing so would support public health actions to get COVID-19 under control — the essential step toward economic recovery — and averting unnecessary harm to families and the economy. The House took an important step in this direction when it passed the Heroes Act, which would provide robust fiscal support to individuals and state and local governments.

As the House, Senate, and White House begin negotiations over the next stimulus package, these are some of the key provisions the package should include:

- Expanded unemployment benefits. Unemployment and underemployment remain high, particularly for people of color, so maintaining an expanded UI program is essential. The package should extend the current eligibility expansions, provide a substantial, federally funded increase above pre-pandemic levels (without the CARES Act, benefits would have averaged only about $320 per week in May), and provide additional weeks of benefits to give unemployed workers more time to find a job when unemployment remains high.

-

Help for those struggling the most. This help should take several forms. First, the package should boost SNAP benefits for all SNAP participants. The House-passed Heroes Act includes a modest, 15 percent increase that would provide roughly $100 per month more to a family of four and, unlike the Families First Act’s SNAP increase, would help all SNAP households, including the poorest households who face the greatest challenges to affording food. Studies show that SNAP benefits are too low even during better economic times; this is particularly problematic during downturns because many participants will be out of work or earning very low pay for longer periods and receive less help from their extended families.

Second, the package should strongly boost funding for rental assistance and homelessness services and prevention. Substantial additional resources are needed for rental assistance to enable more struggling households to pay rent for as long as they need that help. In addition, the homeless services system needs more resources to revamp its services and facilities in order to facilitate social distancing and other health protocols and provide safe non-congregate shelter options whenever possible.

Third, the package should provide emergency grants to states to provide targeted help to families falling through the cracks. Even well-designed relief measures will miss some households and do too little for some others facing serious crises. The package should include funding for states to provide cash or other help to individuals and families at risk of eviction or other serious hardships and to create subsidized jobs for those with the greatest difficulty finding employment, when it is safe to do so.

Fourth, the package should temporarily expand the EITC for workers without minor children at home and the Child Tax Credit for poor and low-income children. Expanding the EITC would help millions of low-wage workers who are now taxed into, or deeper into, poverty because they receive either no EITC or a tiny EITC that doesn’t offset their payroll taxes. Providing the full Child Tax Credit to the 27 million children who now receive no or only a partial credit because their families don’t have earnings or their earnings are too low would help children in economically vulnerable families.[74]

- Robust fiscal relief, with separate components to meet rising needs for Medicaid and to help state and localities avert deep cuts in education, transportation, and services for struggling residents. Even as states’ and localities’ revenues are plummeting, their costs are rising. More people need help through programs like Medicaid because their earnings are falling or they have lost their jobs and job-based health coverage. In addition, public schools and colleges are facing enormous costs to respond to the health crisis, to implement online learning, and (for postsecondary institutions) to cope with reduced tuition revenues. The National Governors Association has called for a robust increase in federal Medicaid funding and grant aid to help address these needs; the Heroes Act includes robust support.

The next package should also reverse the mistake in the CARES Act of excluding many families from relief measures because they include one or more immigrant members who lack a Social Security number. A recent proposal from Senators Marco Rubio and Tom Tillis[75] would partially address this problem, though it falls short of fixing it.

While some policymakers have cited the growing national debt to argue against further stimulus measures, the nation has the “fiscal space” to accommodate the strong fiscal response that this crisis demands. As a recent CBPP report explained, fiscal stimulus can help the economy recover faster and grow more over time, and interest costs on the debt are expected to remain low for the foreseeable future.[76] Large, temporary costs to promote economic health now may add only modestly over time to the debt ratio and the interest payments on that debt. Such stimulus is well worth doing, given the steep cost of providing inadequate support or forcing premature reopenings that would harm public health and the economy.