A Lost Decade in Higher Education Funding

State Cuts Have Driven Up Tuition and Reduced Quality

End Notes

[1] Nicholas Camilien and David Schupak helped gather data for this report.

[2] Elizabeth McNichol and Samantha Waxman, “Many States Face Revenue Shortfalls: States Can Take Steps to Strengthen Their Tax Systems and Reserves,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 20, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/many-states-face-revenue-shortfalls.

[3] This paper uses CPI-U-RS inflation adjustments to measure real changes in costs. Over the past year, the CPI-U-RS increased by 1.25 percent. We use the CPI-U-RS for the calendar year that begins the fiscal/academic year. Unless noted, all figures in this paper are adjusted for inflation.

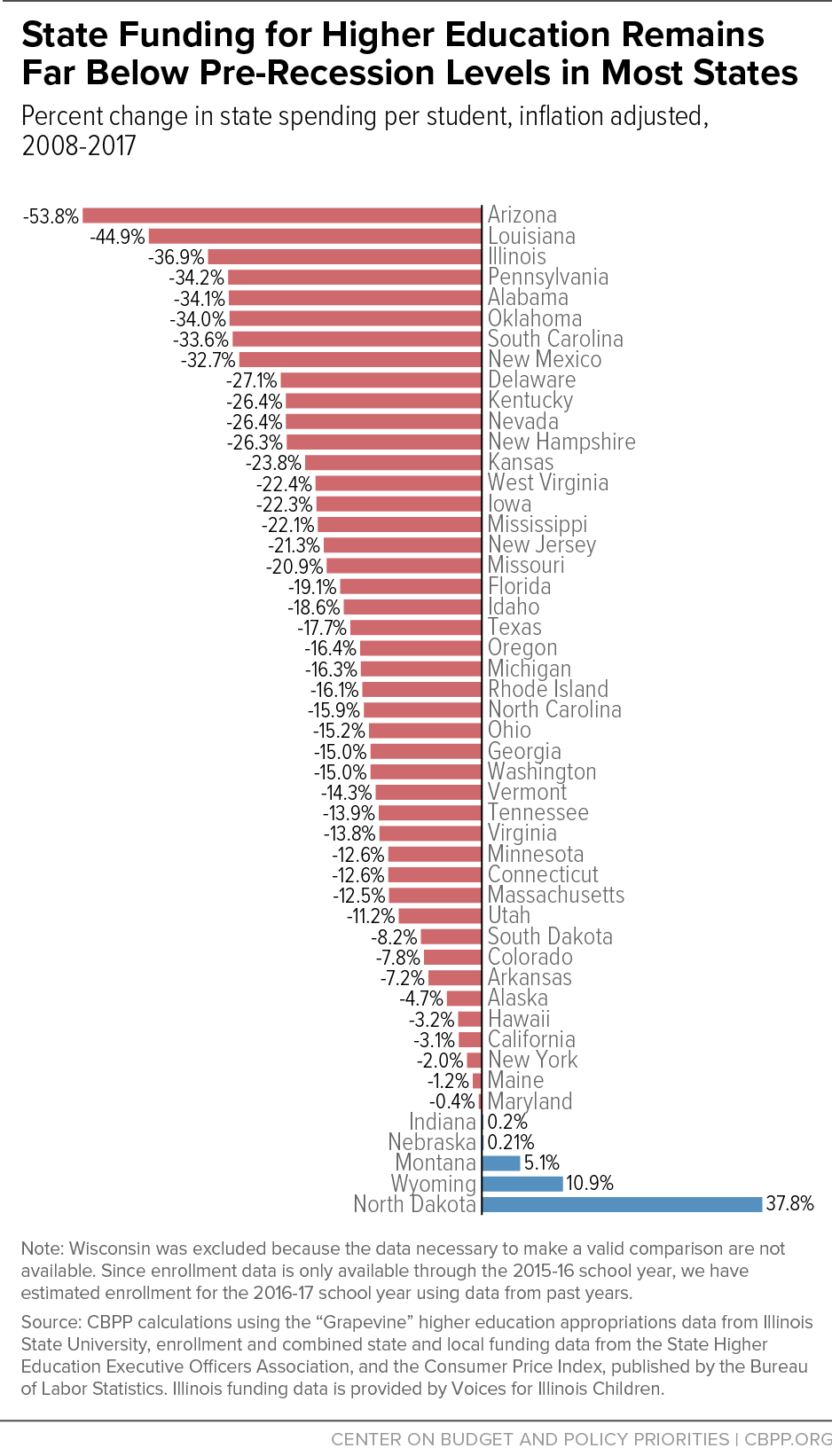

[4] Wisconsin was excluded from this analysis. In the 2013-15 biennial budget, Wisconsin state lawmakers changed the funding model for Wisconsin’s Technical College System, shifting support from the local property tax to state General Purpose Revenue. This change reflects a shift of roughly $406 million in annual support from the local to state levels in Wisconsin but did not result in an overall increase in support for Wisconsin’s higher education institutions. Excluding this shift, per-student funding fell by $1,626, or 24.8 percent, over 2008-2017.

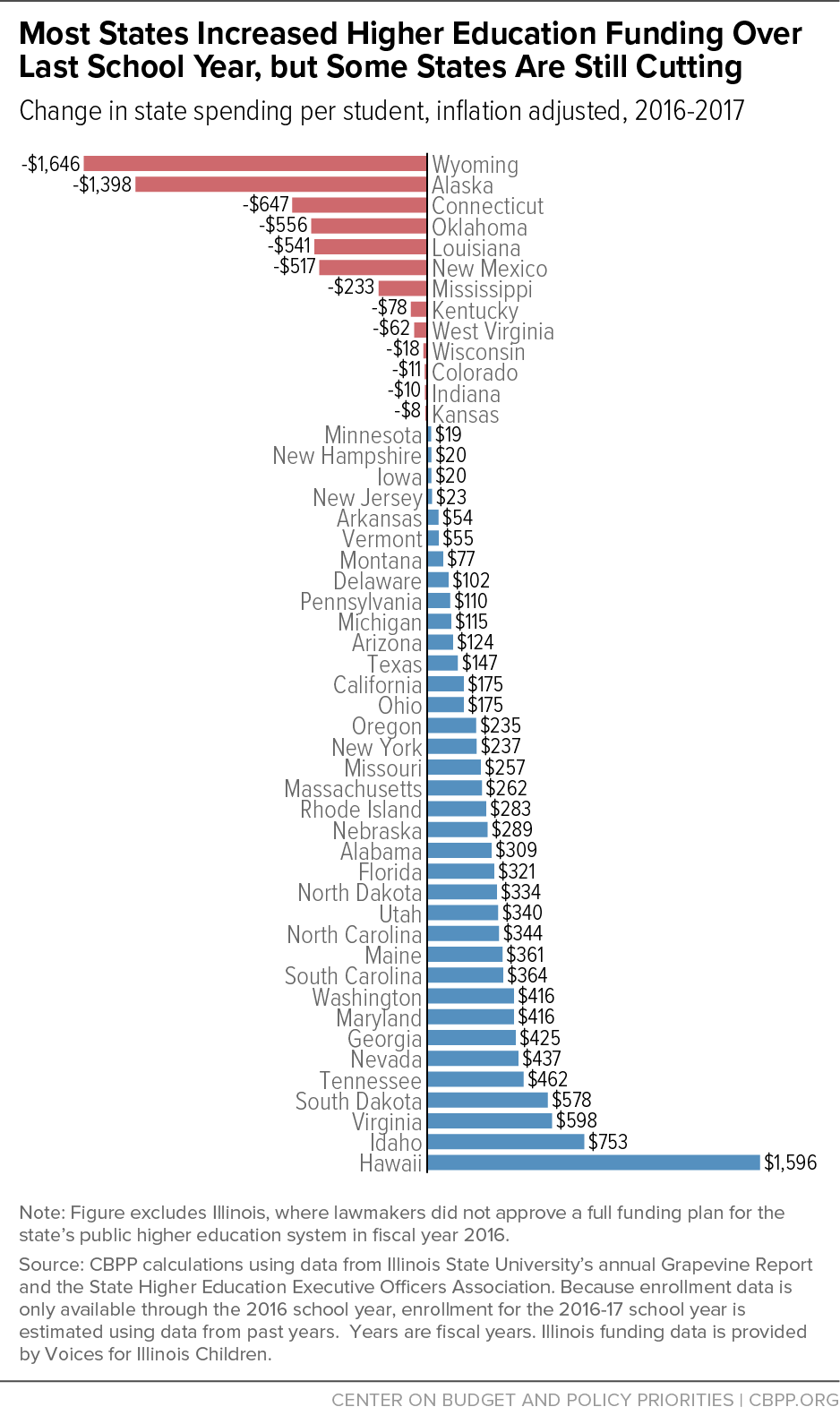

[5] CBPP calculation using the “Grapevine” higher education appropriations data from Illinois State University, enrollment data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, and the Consumer Price Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since enrollment data are available only through the 2016 school year, enrollment for the 2017 school year is estimated using data from past years.

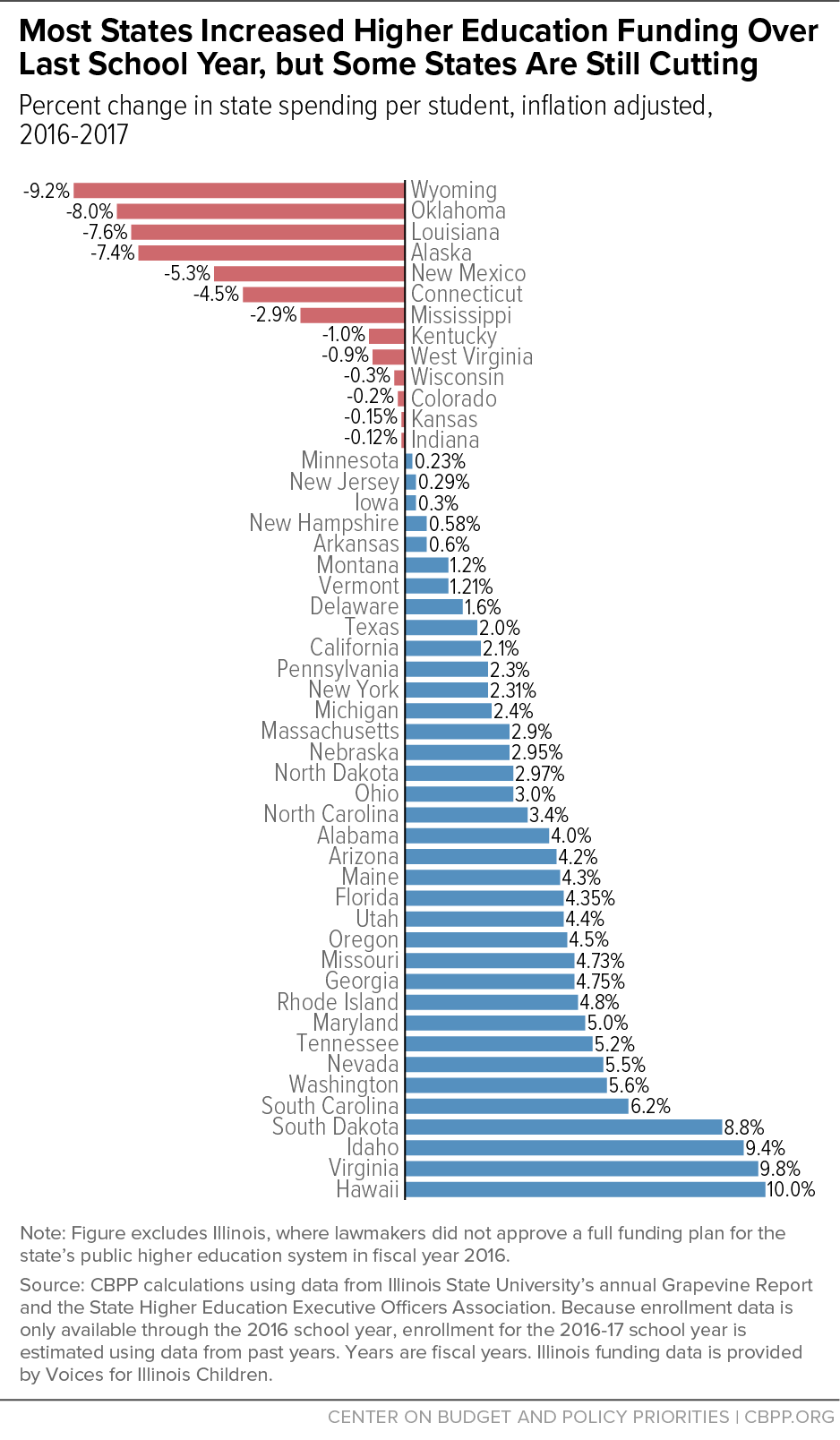

[6] Illinois was excluded from the 2016-2017 analysis because Illinois did not pass a full funding bill for higher education in fiscal year 2016.

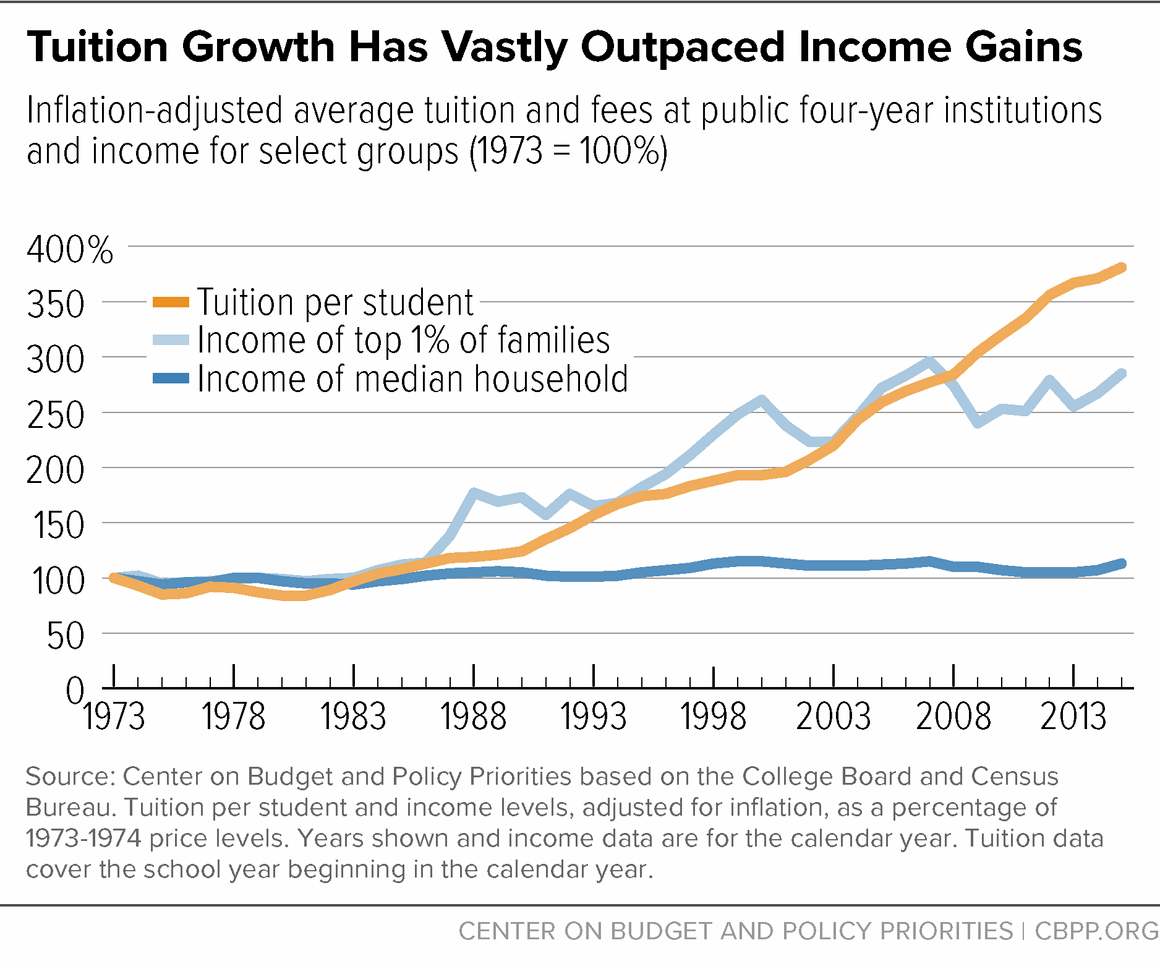

[7] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, “State Higher Education Finance: FY2016,” April 2017, p. 18, http://sheeo.org/sites/default/files/SHEEO_SHEF_2016_Report.pdf.

[8] Calculated from College Board, “Trends in College Pricing 2016: Average Tuition and Fee and Room and Board Charges, 1971-72 to 2016-17 (Enrollment-Weighted),” Table 2, http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing.

[9] Calculated from “Trends in College Pricing 2016,” Table 2, and the Census Bureau’s “Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2015,” September 2016, Table A-1, http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-249.pdf.

[10] Anthony P. Carnevale, Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl, “Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements through 2020,” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, June 2013, https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/tll0zkxt0puz45hu21g6.

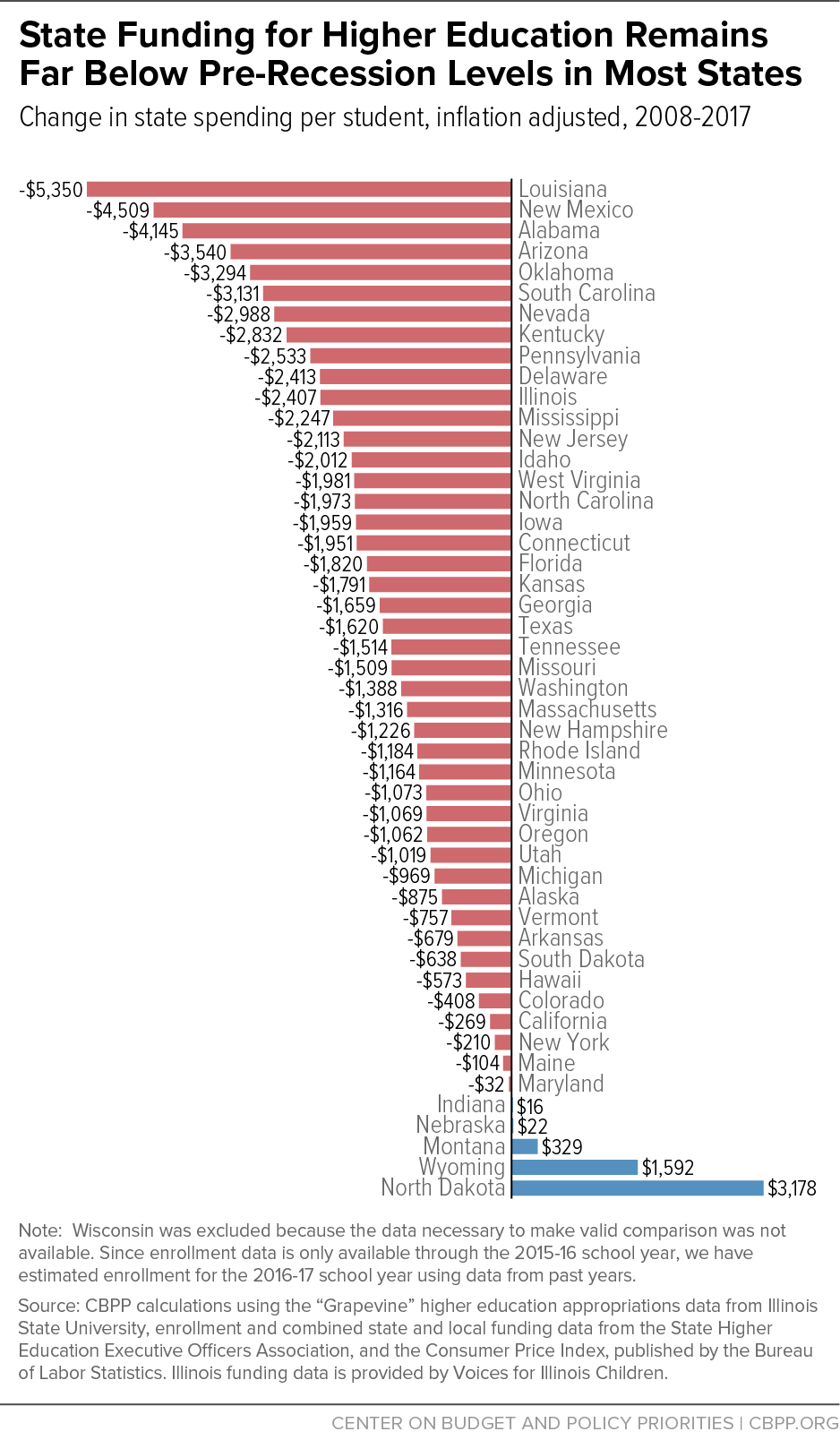

[11] McNichol and Waxman.

[12] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, April 2017.

[13] CBPP calculation using the “Grapevine” higher education appropriations data from Illinois State University, enrollment and combined state and local funding data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, and the Consumer Price Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since enrollment data are only available through the 2016 school year, we have estimated enrollment for the 2017 school year using data from past years. The Illinois system of higher education operated without state appropriations for much of the 2017 school year. In June 2016, the legislature approved $1 billion in higher education funding that could be used for expenses in fiscal year 2016 and the first half of fiscal year 2017. To calculate the amount dispersed for 2017, we spread the $1 billion across the 18-month period (applying two-thirds to 2016 and the rest to fiscal year 2017). In July 2017 lawmakers approved an additional $1.2 billion in funding for the 2017 school year such that the final fiscal year 2017 appropriation totals roughly $1.5 billion.

[14] CBPP analysis of Census quarterly state and local tax revenue, http://www.census.gov/govs/qtax/.

[15] See, for example, “National Postsecondary Enrollment Trends: Before, During and After the Great Recession,” National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, July 2011, p. 6, http://pas.indiana.edu/pdf/National%20Postsecondary%20Enrollment%20Trends.pdf. A survey by the American Association of Community Colleges (AACC) indicated that increases in Fall 2009 enrollment at community colleges were, in part, due to workforce training opportunities; see Christopher M. Mullin, “Community College Enrollment Surge: An Analysis of Estimated Fall 2009 Headcount Enrollments at Community Colleges,” AACC, December 2009, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED511056.pdf.

[16] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, April 2017. While full-time-equivalent enrollment at public two- and four-year institutions is up since fiscal year 2008, between 2014 and 2015 it remained relatively flat after a slight decline in 2013.

[17] National Center for Education Statistics, Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by level and grade: Selected years, fall 1980 through fall 2026, Table 203.10, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_203.10.asp.

[18] CBPP analysis of data from U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

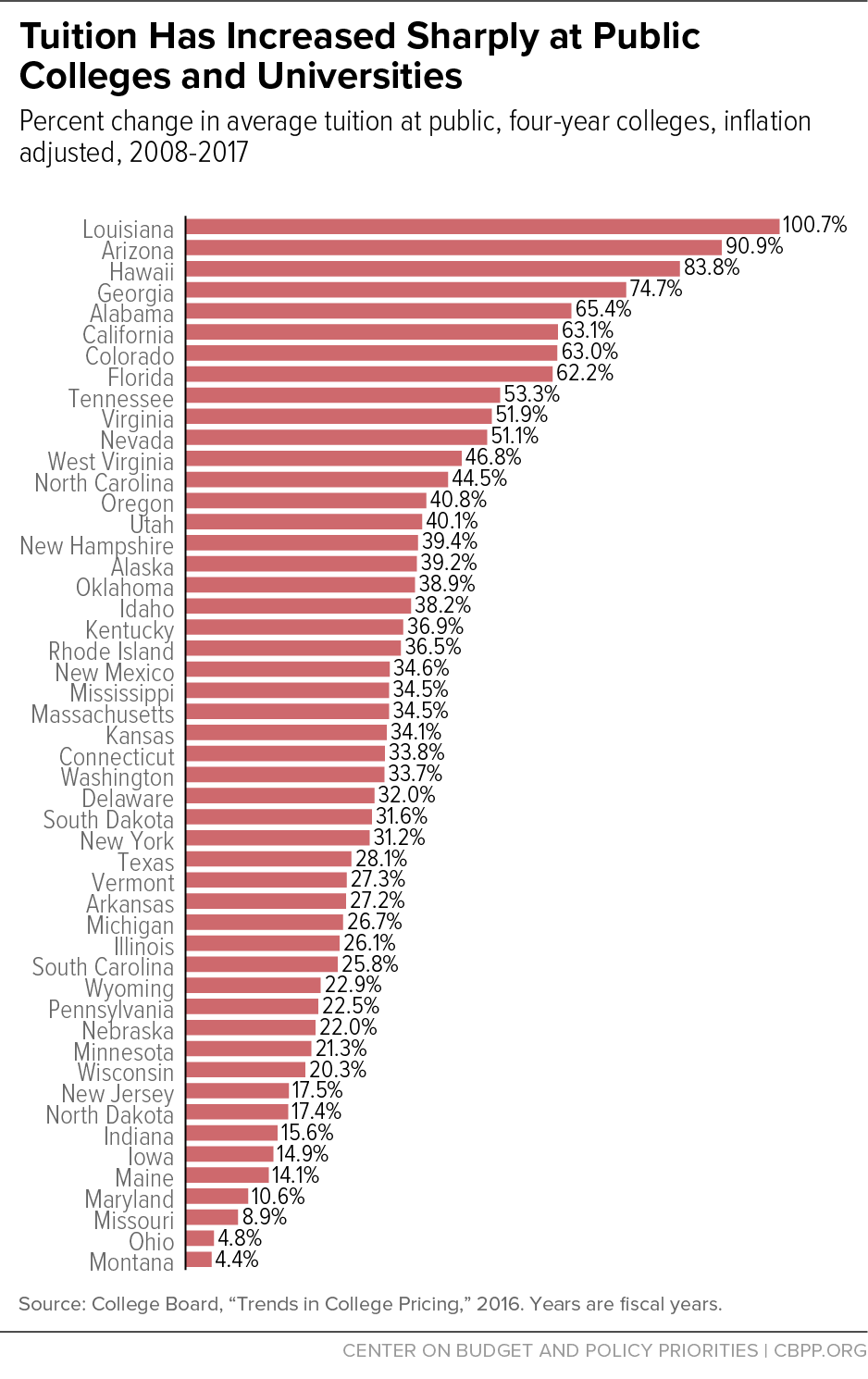

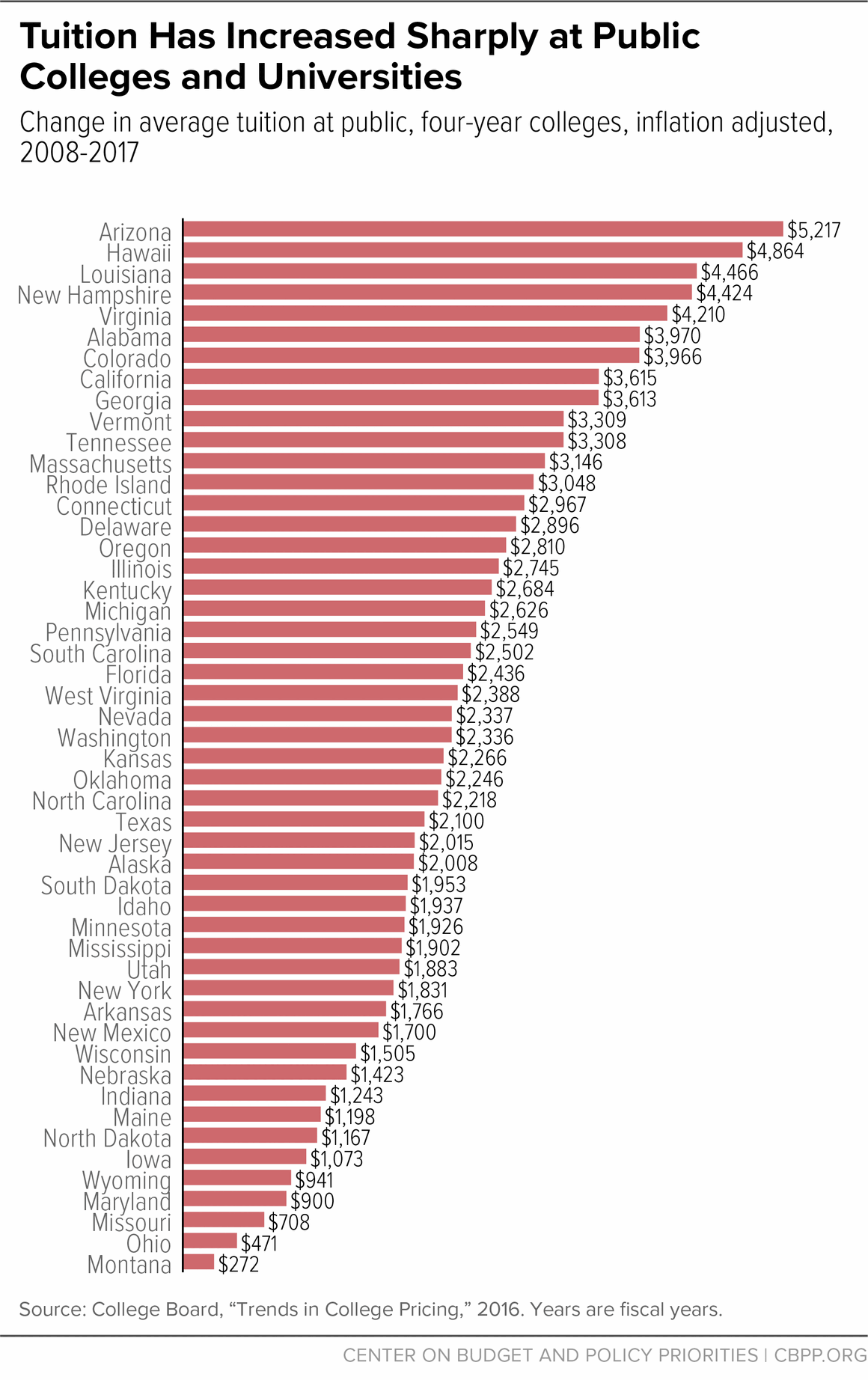

[19] Costs reported above include both published tuition and fees. Average tuition and fee prices are weighted by full-time enrollment.

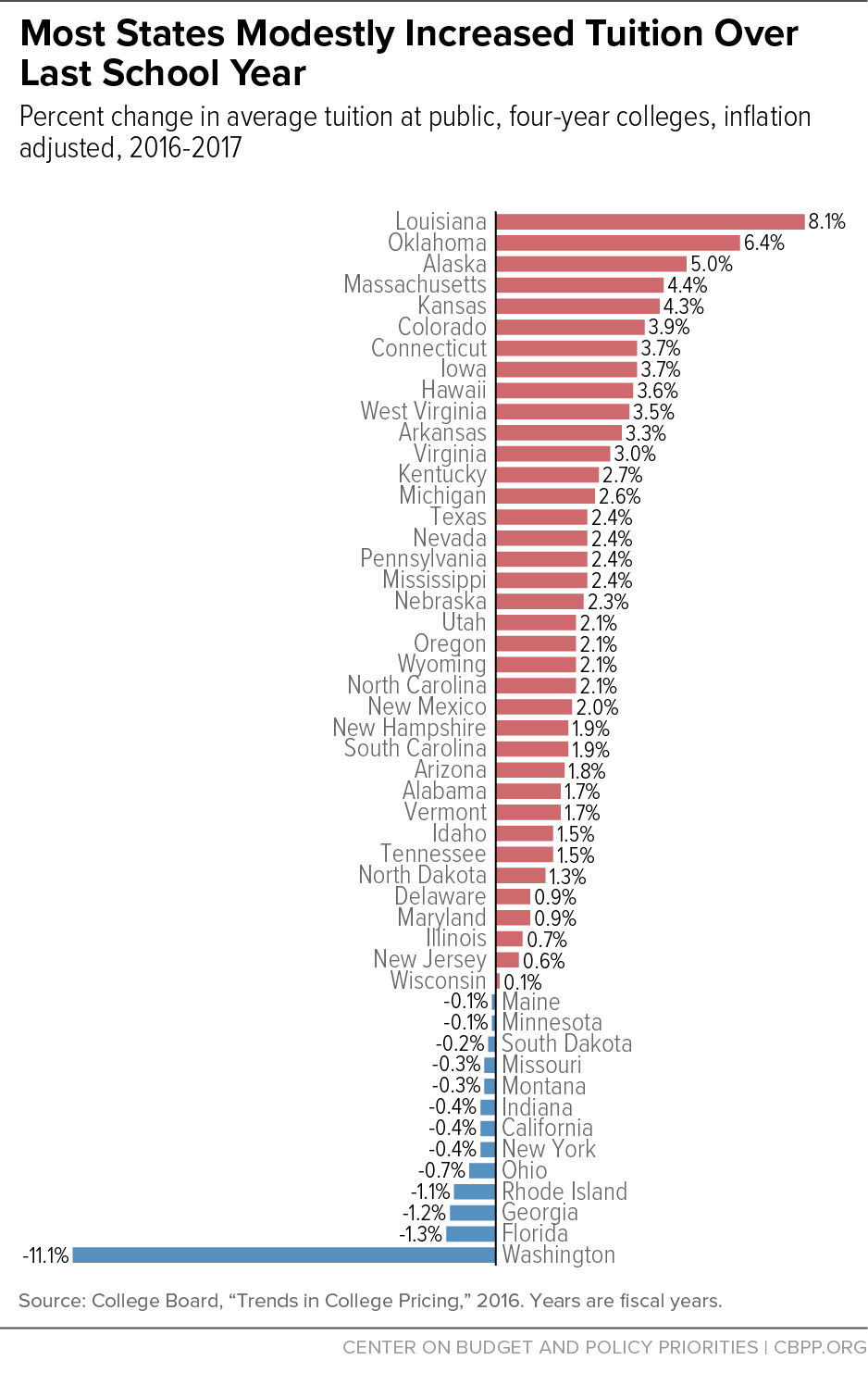

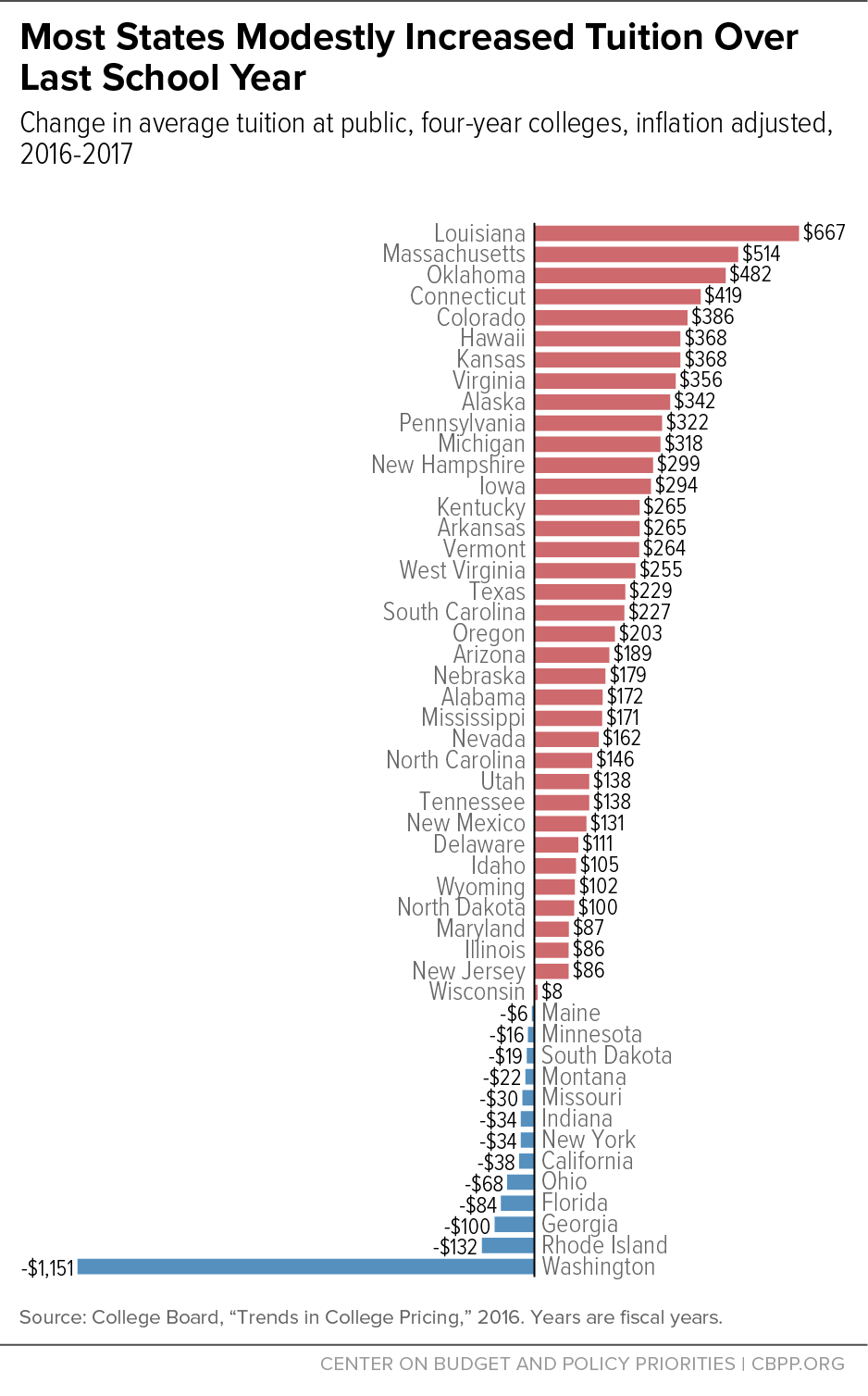

[20] As noted earlier, this and other figures in this report have been adjusted for inflation. Of states with increased tuition, the average tuition increased $242, or 2.6 percent.

[21] CBPP analysis using College Board, “Trends in College Pricing 2016,” https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-college-pricing-web_1.pdf. See appendix for fiscal years 2016-17 change in average tuition at public four-year colleges.

[22] CBPP analysis using College Board, “Trends in College Pricing 2016,” https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-college-pricing-web_1.pdf. In non-inflation-adjusted terms, average tuition is up $3,459 over this period.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

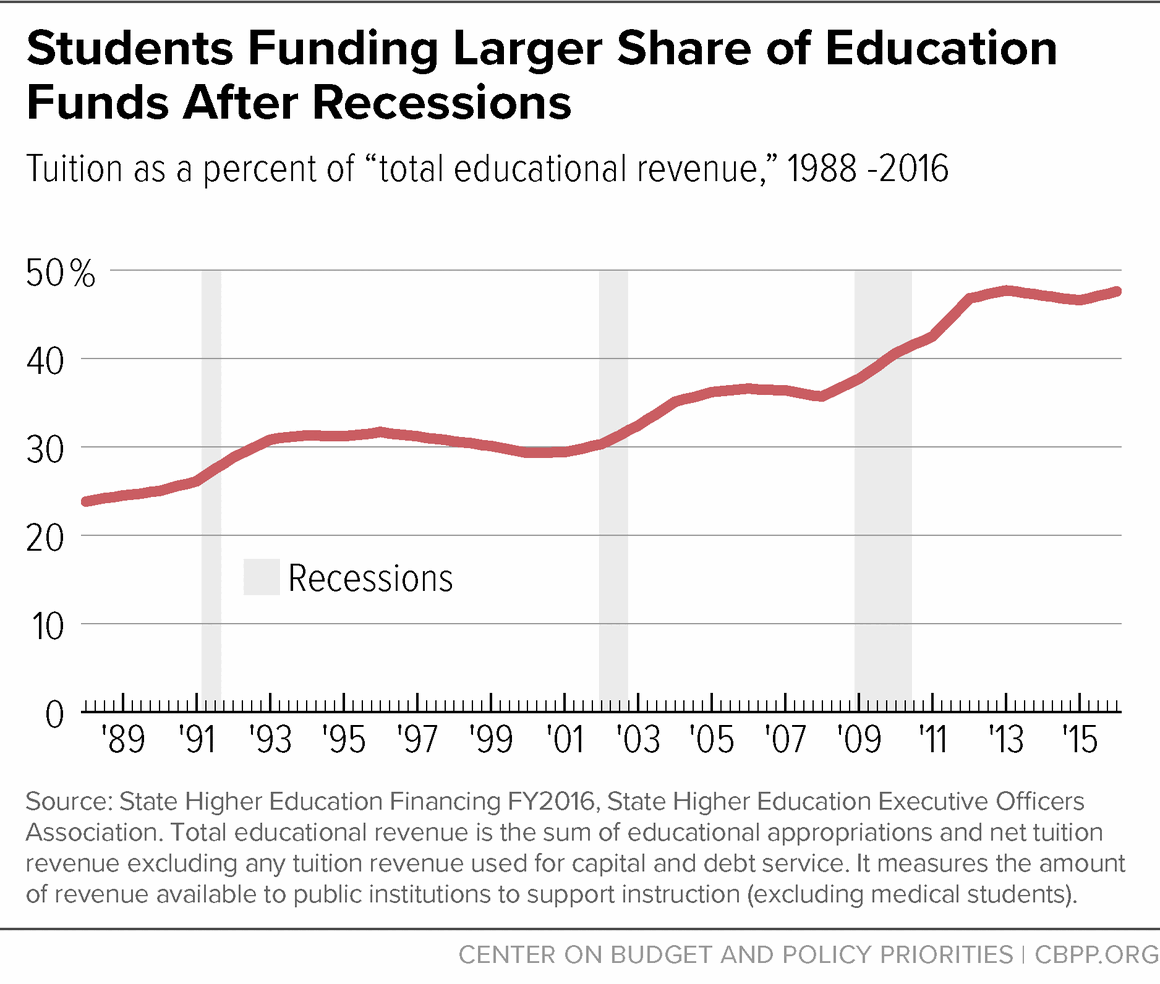

[25] CBPP calculations using State Higher Education Executive Officers data.

[26] For a more detailed account of university cuts, see Michael Mitchell, Vincent Palacios, and Michael Leachman, “States Are Still Funding Higher Education Below Pre-Recession Levels,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 1, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=4135.

[27] Tom Kacich, “Higher-Ed Leaders: More State Cuts Would Be Devastating,” News-Gazette, March 3, 2017, http://www.news-gazette.com/news/local/2017-03-08/higher-ed-leaders-more-state-cuts-would-be-devastating.html.

[28] Sam Zeff, “Kansas Higher Education Takes a Bigger Than Expected Cut, Tuition Could Go Higher,” KCUR, May 18, 2016, http://kcur.org/post/kansas-higher-education-takes-bigger-expected-cut-tuition-could-go-higher#stream/0.

[29] Linda Blackford, “KCTCS cuts 500 faculty, staff positions,” Lexington Herald-Leader, May 18, 2016, http://www.kentucky.com/news/local/education/article78360412.html.

[30] Heath Haussamen, “NMSU releases list of jobs being eliminated,” Las Cruces Sun-News, July 29, 2016, http://www.lcsun-news.com/story/news/education/nmsu/2016/07/29/nmsu-releases-list-jobs-being-eliminated/87730818/.

[31] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, “State Higher Education Finance: FY2016,” 2017, p. 25, Figure 5, http://sheeo.org/sites/default/files/SHEEO_SHEF_2016_Report.pdf.

[32] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, April 2017; government funding includes both state and local funding sources.

[33] See, for example, Steven W. Hemelt and Dave E. Marcotte, “The Impact of Tuition Increases on Enrollment at Public Colleges and Universities,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, September 2011; Donald E. Heller, “Student Price Response in Higher Education: An Update to Leslie and Brinkman,” Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 68, No. 6 (November-December 1997), pp. 624-659.

[34] Drew Allen and Gregory C. Wolniak, “Exploring the Effects of Tuition Increases on Racial/Ethnic Diversity at Public Colleges and Universities,” New York University, 2015, p. 30, http://www.aera.net/Portals/38/Newsroom%20-%20Recent%20Research/Exploring%20the%20Effects%20of%20Tuition%20Increases%20on%20Racial-Ethnic%20Diversity%20at.pdf.

[35] Stella Flores and Justin Shepard, “Pricing Out the Disadvantaged? The Effect of Tuition Deregulation in Texas Public Four-Year Institutions,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 655, 2014, pp. 99-122.

[36] National Center for Education Statistics, “Total fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by level and control of institution and race/ethnicity of student: Selected years, 1976 through 2015,” Table 306.20, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_306.20.asp.

[37] Thomas J. Kane, “Rising Public College Tuition and College Entry: How Well Do Public Subsidies Promote Access to College?” National Bureau of Economic Research, 1995, http://www.nber.org/papers/w5164.pdf?new_window=1.

[38] Eric P. Bettinger et al., “The Role of Simplification and Information in College Decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA Experiment,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009, http://www.nber.org/papers/w15361.pdf. For details on the disparity in access to counseling for low-income students, see “Course, Counselor, and Teacher Gaps: Addressing the College Readiness Challenge in High-Poverty High Schools,” Center for Law and Social Policy, June 2015, http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/publication-1/CollegeReadinessPaperFINALJune.pdf.

[39] College Board, “Education Pays: 2016,” https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2016-full-report.pdf.

[40] In a 2008 piece, Georgetown University scholar Anthony Carnevale pointed out that “among the most highly qualified students (the top testing 25 percent), the kids from the top socioeconomic group go to four-year colleges at almost twice the rate of equally qualified kids from the bottom socioeconomic quartile.” Anthony P. Carnevale, “A Real Analysis of Real Education,” Liberal Education, Fall 2008, p. 57.

[41] Christopher Avery and Caroline M. Hoxby, “The Missing ‘One Offs’: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low-Income Students,” National Bureau for Economic Research, Working Paper 18586, 2012, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/spring-2013/2013a_hoxby.pdf.

[42] Patrick T. Terenzini, Alberto F. Cabrera, and Elena M. Bernal, “Swimming Against the Tide,” College Board, 2001, http://www.collegeboard.com/research/pdf/rdreport200_3918.pdf.

[43] Eleanor W. Dillon and Jeffrey A. Smith, “The Determinants of Mismatch Between Students and Colleges,” National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19286. Additionally, other studies have found that undermatching is more likely to occur for students of color. In 2009 Bowen, Chingos, and McPherson found that undermatching was more prevalent for black students — especially black women — than for comparable white students.

[44] Stacey Dale and Alan Krueger, “Estimating the Return to College Selectivity Over the Career Using Administrative Earning Data.” Mathematica Policy Research and Princeton University, February 2011, https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/estimating-the-return-to-college-selectivity-over-the-career-using-administrative-earning-data.

[45] College Board, “Trends in Student Aid 2016,” October 2016, Table 8, https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-student-aid_0.pdf.

[46] College Board, “Trends in Student Aid 2016,” October 2016, Figure 17, https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-student-aid_0.pdf.

[47] CBPP calculation using “Trends in College Pricing 2016,” October 2016, Table 7, https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-college-pricing-web_1.pdf.

[48] Spiros Protopsaltis and Sharon Parrott, “Pell Grants — a Key Tool for Expanding College Access and Economic Opportunity — Need Strengthening, Not Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 27, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/pell-grants-a-key-tool-for-expanding-college-access-and-economic-opportunity.

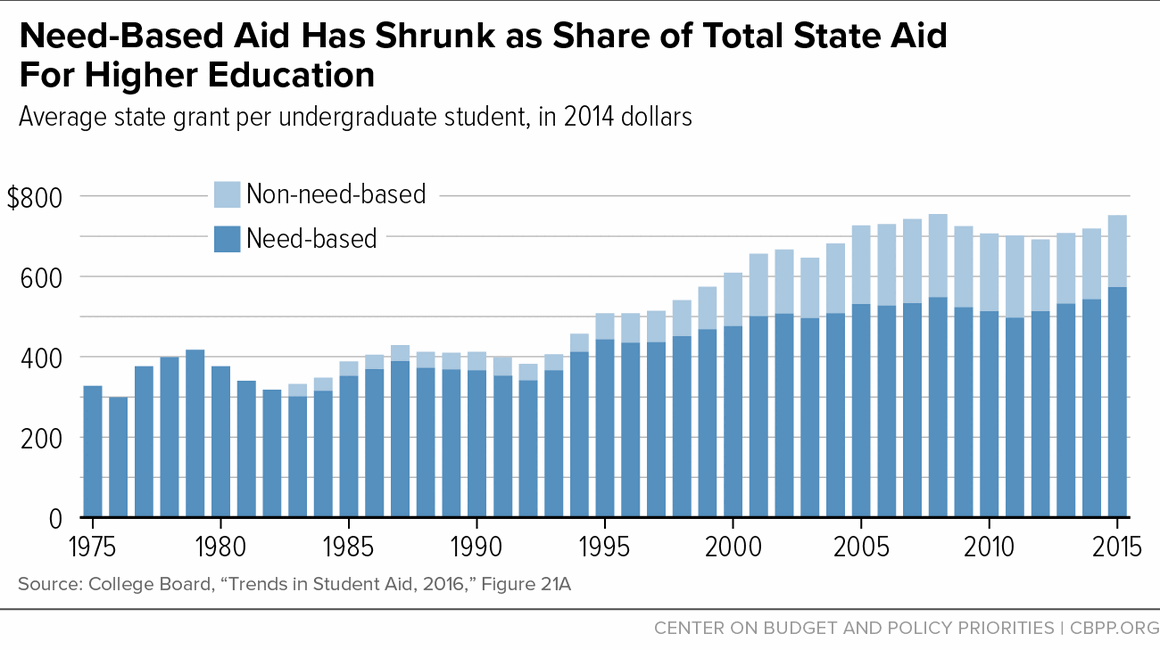

[49] “45th Annual Survey Report on State-Sponsored Student Financial Aid,” National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs, 2016, https://www.nassgap.org/viewrepository.aspx?categoryID=3#collapse_421.

[50] College Board, “Trends in Student Aid 2016,” October 2016, Figure 28A, https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-student-aid_0.pdf.

[51] “45th Annual Survey Report on State-Sponsored Student Financial Aid,” National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs, 2016, https://www.nassgap.org/viewrepository.aspx?categoryID=3#collapse_421.

[52] Donald Heller and Patricia Marin, eds., “State Merit Scholarship Programs and Racial Inequality,” Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University, 2004, https://www.nmefoundation.org/getmedia/78d0251f-ee9d-4410-9645-ac16392be40c/heller-marin-state-merit-scholarship-2004.

[53] Liang Zhang and Erik C. Ness, “Does State Merit-Based Aid Stem Brain Drain?”, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Vol. 32, No. 2, (June 2010), pp 143-165, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40732415?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[54] Eric Bettinger, “How Financial Aid Affects Persistence,” National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2004, http://www.nber.org/papers/w10242.

[55] College Board, “Net Tuition and Fees, Net Room and Board and Other Costs, and Total Grant Aid in 2011 Dollars by Family Income, Full-Time Dependent Students at Public Institutions, 1999-2000, 2003-04, 2007-08, and 2011-12,” Figure 2013_12, October 2014, http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/trends-college-pricing-web-final-508-2.pdf.

[56] College Board, “Trends in Student Aid, 2015: Median Debt Levels of 2007-08 Bachelor’s Degree Recipients by Income Level,” October 2015, 2014_14b, http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/trends-student-aid-web-final-508-2.pdf. Low-income dependent students are defined as students from families earning less than $30,000 annually, while high-income students come from families earning more than $106,000.

[57] Mark Huelsman, “The Debt Divide: The Racial and Class Bias Behind the ‘New Normal’ of Student Borrowing,” May 2015, http://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/Mark-Debt%20divide%20Final%20(SF).pdf. Hispanic or Latino students generally borrow at levels equal to the national average. African American students are also more likely to take on student debt to finance education at two-year colleges.

[58] College Board “Trends in Student Aid 2015,” Figure 15, October 2015, http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/trends-student-aid-web-final-508-2.pdf, and College Board, “Trends in Student Aid 2016,” Figure 13, October 2016, https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-student-aid_0.pdf.

[59] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit,” May 2017, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2017Q1.pdf

[60]Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis, “A Crisis in Student Loans? How Changes in the Characteristics of Borrowers and in the Institutions They Attended Contributed to Rising Loan Defaults,” Brookings Institution, BPEA Conference Draft, September 10, 2015, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/fall-2015_embargoed/conferencedraft_looneyyannelis_studentloandefaults.pdf.

[61] See, for example, Kent Hill et al., “The Value of Higher Education: Individual and Societal Benefits,” October 2005, http://www.asu.edu/president/p3/Reports/EdValue.pdf and College Board, “Education Pays 2013,” October 2013, http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2013-full-report-022714.pdf for summaries of the social benefits of higher levels of educational attainment.

[62] Enrico Moretti, “Estimating the Social Return to Higher Education: Evidence from Longitudinal and Repeated Cross-Sectional Data,” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 121, 2004, pp. 175-212.

[63] See Carnevale, Smith, and Strohl.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Beth Akers, “Higher education debt is worth it, but isn’t risk free,” Brookings Institution, January 12, 2016, http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2016/01/12-higher-education-debt-akers.

[66] For impacts of debt on homeownership, see Jennifer M. Shand, “The Impact of Early-Life Debt on the Homeownership Rates of Young Households: An Empirical Investigation,” Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, November 2007. For the relationship between debt and graduation, see for example, Rachel E. Dwyer, Laura McCloud, and Randy Hodson, “Debt and Graduation from American Universities,” Social Forces, June 15, 2012, http://sf.oxfordjournals.org/content/90/4/1133. For information on graduate enrollment, see for example Lindsey E. Malcolm and Alicia C. Dowd, “The Impact of Undergraduate Debt on the Graduate School Enrollment of STEM Baccalaureates,” Review of Higher Education, Volume 35, No. 2, Winter 2012, pp. 265-305.

[67] Brent W. Ambrose, Larry Cordell, and Shuwei Ma, “The Impact of Student Loan Debt on Small Business Formation,” March 29, 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2417676.

[68] McNichol and Waxman.

[69] Iris Lav and Michael Leachman, “The Trump Budget’s Massive Cuts to State and Local Services and Programs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 13 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/the-trump-budgets-massive-cuts-to-state-and-local-services-and.

[70] Michael Leachman et al., “Most States Have Cut School Funding, and Some Continue Cutting,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 25, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/most-states-have-cut-school-funding-and-some-continue-cutting.

[71] Elizabeth McNichol, “It’s Time for States to Invest in Infrastructure,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 10, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/its-time-for-states-to-invest-in-infrastructure.

[72] Data from the National Association of State Budget Officers.

[73] Nicholas Johnson and Michael Leachman, “Four Big Threats to State Finances Could Undermine Future U.S. Prosperity,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 14, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/four-big-threats-to-state-finances-could-undermine-future-us-prosperity.