During times of economic growth, states can be reasonably confident that the tax collections upon which they base their budgets will come in as predicted. Last fiscal year was different, however. In 2017, 22 states faced revenue shortfalls. More states faced mid-year revenue shortfalls in the last fiscal year than in any year since 2010, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.[1]

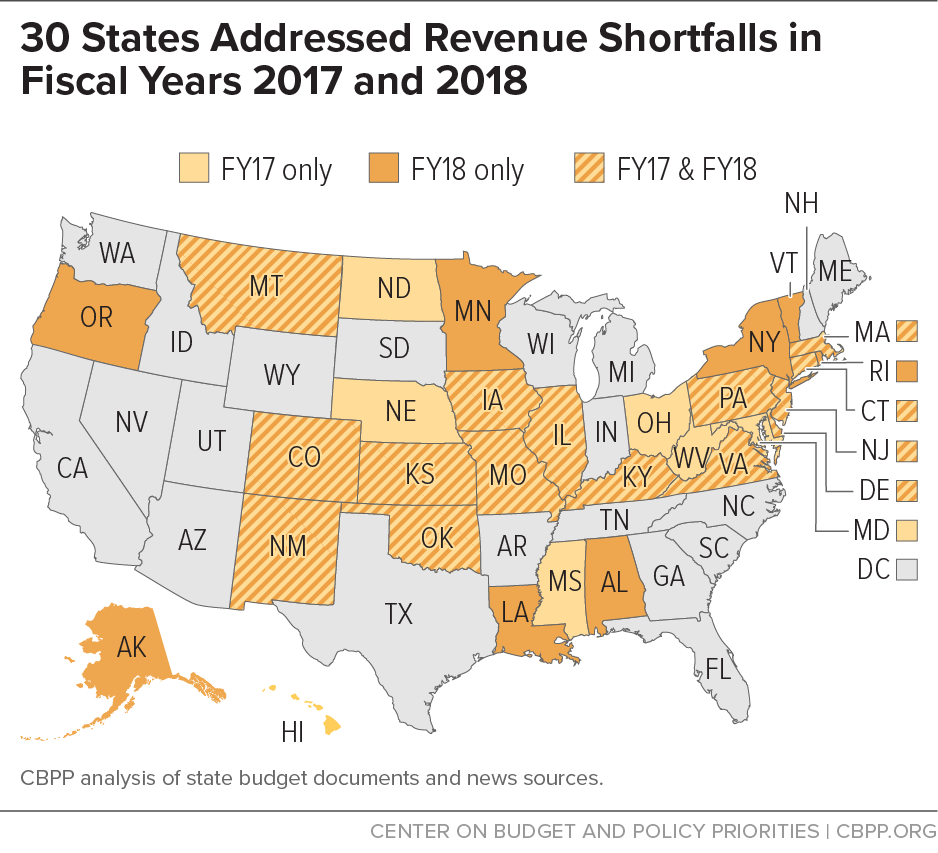

The fiscal year 2017 revenue shortfalls and resulting budget problems — some of which were due to state policymakers’ own ill-advised tax policy choices — were the first signs of continuing problems. Close to half the states lacked the revenue needed to maintain services at existing levels in 2018 when they began their budget deliberations. All told, 30 states have addressed revenue shortfalls in fiscal years 2017, 2018, or both. (See Figure 1 and Table 1.)

States cut spending, increase revenues, or tap rainy day funds or other reserves to close budget gaps and maintain a balanced budget, which all states do because of laws or tradition. In 2017, most states used reserve funds and spending cuts to balance their budgets. Policymakers in some states, including Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, and New York, increased taxes to help address their shortfall.

While states cannot control all of the factors contributing to their budget uncertainty — for example, potential cuts to federal grants that comprise nearly a third of their budgets — they can take a number of steps now to strengthen their tax systems and reserves that will protect revenues in the coming years.

Despite the continued national economic recovery, state revenue growth is slowing. This slowdown does not appear to be the harbinger of a recession, but rather the result of many factors mostly, but not entirely, outside of states’ control. States could also do a better job of planning for uncertainties.

- Falling energy prices. States with energy-based economies have seen energy-related taxes plummet as oil prices have dropped. The states with the greatest reliance on energy taxes like Alaska, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and West Virginia have struggled with budget problems since oil prices began to fall in 2014.[2]

- Tax cuts. Costly and ill-advised tax cuts enacted in recent years are suppressing some states’ tax collections. For example, 11 states have enacted large, phased-in tax cuts since 2011 that will cost a combined $8 billion a year once fully implemented.[3] Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, North Carolina, New Jersey, and New York enacted multi-year tax cuts that continued into 2017, with some of those cuts extending into 2018 and beyond.[4]

-

Stock market growth and a possible “Trump effect.” Sluggish stock market growth in 2015 and the beginning of 2016 slowed income tax collections. The stock market rebounded starting in late 2016, but income tax collections are now lagging expectations as wealthy taxpayers may be postponing selling stocks and other assets in the hope that President Trump and Congress will cut capital gains tax rates.[5]

This is a known phenomenon that was last seen when wealthy taxpayers took capitals gains at the end of 2012 rather than waiting until 2013 in order to avoid potentially higher tax rates as the “fiscal cliff” loomed. A similar pattern — but in reverse — may be happening now. President Trump campaigned on and proposed in April 2017 a tax package that included reduced rates on capitals gains and other income.[6] Initially, these tax changes were expected to happen in 2017, the first year of the new administration. This created the incentive at the end of 2016 for wealthy individuals to postpone taking capital gains until the following year so that the resulting income would be taxed in 2017 at the new lower rates.

Taxpayers with large holdings of assets like stocks whose sales generate taxable capital gains generally pay estimated tax payments throughout the year because unlike wages this income is not subject to withholding. Each April, they determine the actual amount owed based on actual income and then receive a refund or pay any additional amount owed. Thus, if a significant number of taxpayers postponed taking capital gains in 2016, we would expect to see lower-than-expected income tax collections in April 2017 (when 2016 tax returns were filed). Preliminary data on estimated state income tax payments show this pattern but data from later in the year is needed to determine if this is, in fact, the result of a timing shift rather than an actual decline in income.[7]

- Slower-than-average sales tax collection growth. Despite the economic recovery, growth in sales tax collections is below its historical average as consumers have remained cautious long after the end of the recession and untaxed Internet sales have continued to grow. “State sales tax revenue grew 1.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2016, down from an average of 2.3 percent in the four previous quarters,” according to a recent analysis of Census data by the Rockefeller Institute of Government.[8]

Some state officials are concerned that these shortfalls may be a harbinger of a national economic slowdown. A recession would have significant, multi-year implications for a state’s ability to fund services in the future. In contrast, a temporary slowdown in revenues that results from taxpayer behavior in anticipation of tax cuts, for example, is much easier to cope with.

For now, the national economy appears to be continuing to expand. There are no obvious imbalances, like the housing or dot-com bubbles that preceded the last two recessions. Real gross domestic product growth is relatively steady and was higher in second quarter of 2017 (3.1 percent) than in the first quarter (1.2 percent).[9] In addition, employment continues to grow and the unemployment rate is low.[10] Finally, in part because inflation remains low, the Federal Reserve is avoiding actions that would shock the economy into slowing.

Slowing revenues are just one element of uncertainty about how states will be able to meet their responsibilities. Federal grants to states — which make up approximately 31 percent of state budgets — are at risk of being cut based on proposals from President Trump and congressional Republicans,[11] though at this stage in the federal budget process it is unclear how deep these cuts may be.

The prospect of changes to the federal tax system, as President Trump and congressional Republicans intend to propose, could also have major state revenue implications. Most state income taxes are based on federal definitions of income. Increases in certain deductions, such as allowing immediate expensing of the full cost of some investments, could result in state revenue losses. The elimination of the federal estate tax could make it more difficult for states with estate taxes to retain them. On the other hand, broadening the income tax base to make more income taxable — to offset federal rate cuts — could modestly increase state revenues.

To prevent and cope with revenue slowdowns that are leading to budget problems, states should:[12]

Avoid ineffective tax cuts and incentives that would deplete revenues and worsen budget problems. Several states have enacted or considered deep income tax cuts that give the largest benefits to large, profitable corporations and the highest-income people. Such proposals not only typically fail to produce the promised economic benefits but also squander revenue that states could otherwise use to lay a strong foundation for future economic growth by investing in high-quality schools, infrastructure, and the like. They also make it harder for states to save for a rainy day or respond to changing circumstances.

Avoid depleting budget reserves while the economy continues to grow and, if possible, build budget reserves to protect public investment and limit the damage from recessions.[13] “Rainy day” reserve funds to help states offset revenue declines during economic downturns are crucial to prudent fiscal management. In hard times, policymakers can tap them to protect state investments that promote economic growth and sustain the state’s demand for private-sector goods and labor. States without such funds should create them; states with arbitrary or onerous restrictions on the use of their reserves should reform their rules.

Rainy day reserves will be particularly important for states to cope with reduced state revenues if the federal government plays a smaller role during future economic downturns. For example, proposals to cut federal support for low-income health care or food assistance through fixed funding (block grants) or other types of caps would make these programs less responsive to economic downturns.

Begin now to plan for revenue replacements to offset the potential future loss of federal support. Maintaining and improving schools, affordable housing, job training, and other public services shown to generate growth will require resources, both now and in the future. President Trump and congressional Republicans have proposed steep cuts in federal support for programs and services delivered by states and localities. For example, the President’s budget would cut state and local discretionary grants by $18 billion in 2018.[14] These federal grants include support for education, including support for high-poverty schools, support for child care programs, and programs to subsidize housing for low-income families and seniors and foster community development.

To make up the difference if these cuts are enacted, states should consider raising their own revenues. Tax increases on high-income individuals and profitable corporations (those best able to afford the higher tax and least likely to spend substantially less as a result) typically are preferable to spending cuts. This is especially true when the cuts in question could weaken the underpinnings of a sound economy — a high-quality education system, access to college, and modern transportation networks, for example.

Reject artificial spending limits. Strict, arbitrary formulas to limit revenues and spending, like Colorado’s “Taxpayer Bill of Rights” or TABOR, may sound appealing but are gimmicks that hamstring a state’s ability to adapt to changing needs and voter demands.[15] They are especially problematic in uncertain times like this. States will need flexibility, not strict limits like TABOR, to raise revenues or increase their own support for programs and services to respond to likely cuts in federal funding over the next few years, or to respond to other emergencies or changing circumstances.

Address structural problems in state revenue systems. Antiquated tax systems ill-suited to the 21st century economy hamper states’ ability to restore school funding, cope with cuts in federal support, and invest in the future. For instance, many states primarily levy sales taxes on tangible goods, even though services — many of which didn’t exist when sales taxes were enacted, such as video streaming — make up a growing share of consumption. States can halt the erosion of their sales taxes and improve their long-term ability to invest in state priorities by broadening the sales tax to include more services. In addition, states should diversify revenue sources, including sales, excise and/or income taxes, each of which responds differently to economic changes, to improve the stability of tax collections.[16]

This report focuses on states where revenues are falling short of the amount expected or of the amount needed to maintain current services. (See note at the end of Table 1.) Other states that do not appear in our count and on the list in Table 1 are also at risk of failing to provide the investments needed to grow the state economy now or in the future. For example, some states have chronically underfunded education, health care, transportation, and other services or rely on tax systems with structural problems that are not yet evident. In addition, many states do not regularly publish estimates of the cost of maintaining current services, making it difficult to identify shortfalls in future budgets.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| State |

FY17 Revenue Shortfall, millions* |

% General Fund** |

Shortfall Addressed in FY18, millions* |

% General Fund** |

|---|

| Alabama |

0 |

0% |

-465 |

6% |

| Alaska*** |

0 |

0% |

-2,500 |

58% |

| Colorado |

-137 |

1% |

-172 |

2% |

| Connecticut |

-467 |

3% |

-2,300 |

13% |

| Delaware |

-67 |

2% |

-386 |

9% |

| Hawaii |

-183 |

2% |

0 |

0% |

| Illinois*** |

-810 |

2% |

-6,646 |

20% |

| Iowa |

-399 |

5% |

-163 |

2% |

| Kansas |

-222 |

4% |

-351 |

6% |

| Kentucky |

-139 |

1% |

-206 |

2% |

| Louisiana |

0 |

0% |

-440 |

5% |

| Maryland |

-435 |

3% |

0 |

0% |

| Massachusetts |

-431 |

1% |

-749 |

2% |

| Minnesota |

0 |

0% |

-185 |

1% |

| Mississippi |

-169 |

3% |

0 |

0% |

| Missouri |

-71 |

1% |

-251 |

3% |

| Montana |

-76 |

3% |

-131 |

6% |

| Nebraska |

-301 |

7% |

0 |

0% |

| New Jersey |

-527 |

2% |

-413 |

1% |

| New Mexico |

-69 |

1% |

-70 |

1% |

| New York |

0 |

0% |

-2,106 |

3% |

| North Dakota |

-133 |

4% |

0 |

0% |

| Ohio |

-849 |

2% |

0 |

0% |

| Oklahoma*** |

-176 |

3% |

-214 |

4% |

| Oregon |

0 |

0% |

-800 |

8% |

| Pennsylvania*** |

-1,500 |

5% |

-700 |

2% |

| Rhode Island |

0 |

0% |

-134 |

4% |

| Texas*** |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

| Vermont |

0 |

0% |

-76 |

5% |

| Virginia |

-245 |

1% |

-850 |

4% |

| Washington*** |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

| West Virginia |

-121 |

3% |

0 |

0% |

| All States |

$7,527 |

2% |

$20,309 |

5% |

| TABLE 2 |

|---|

| State |

FY17 |

FY18 |

|---|

| Alabama |

Arise Citizens Policy Project |

Arise Citizens Policy Project |

| Alaska |

None |

Alaska Dispatch News |

| Colorado |

Colorado Legislative Council Staff |

Colorado Legislative Council Staff |

| Connecticut |

State of Connecticut Office of Policy and Management |

Connecticut Mirror |

| Delaware |

Delaware Economic & Financial Advisory Council |

Delaware Online |

| Hawaii |

Hawaii Council on Revenues |

None |

| Illinois |

Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability |

Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability |

| Iowa |

Iowa Revenue Estimating Conference & Legislative Service Agency |

Iowa Revenue Estimating Conference & Legislative Service Agency |

| Kansas |

Kansas Division of the Budget |

Kansas Center for Economic Growth |

| Kentucky |

Kentucky Office of the State Budget Director |

Kentucky Office of the State Budget Director |

| Louisiana |

The Advocate |

Louisiana Division of Administration |

| Maryland |

State of Maryland Board of Revenue Estimates |

None |

| Massachusetts |

Massachusetts Department of Revenue |

Office of the Governor |

| Minnesota |

Minnesota Management and Budget |

Minnesota Management and Budget |

| Mississippi |

Mississippi Legislative Budget Office |

None |

| Missouri |

Missouri Office of Administration, Division of Budget & Planning |

Missouri Office of Administration, Division of Budget & Planning |

| Montana |

Montana Legislative Branch, Legislative Fiscal Division |

Governor’s Office of Budget and Program Planning |

| Nebraska |

Nebraska Department of Revenue |

Nebraska Legislature |

| New Jersey |

New Jersey State Senate, Budget & Appropriations Committee |

NJ.com |

| New Mexico |

State of New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee |

State of New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee |

| New York |

None |

New York State Division of the Budget |

| North Dakota |

North Dakota Legislative Council |

None |

| Ohio |

Policy Matters Ohio |

None |

| Oklahoma |

Oklahoma Office of Management & Enterprise Services |

Oklahoma Watch |

| Oregon |

None |

Oregon Legislative Fiscal Office & Joint Committee on Ways and Means |

| Pennsylvania |

The Morning Call |

The Morning Call |

| Rhode Island |

WPRI |

State of Rhode Island House of Representatives |

| Texas |

None |

None |

| Vermont |

None |

Vermont Agency of Administration, Department of Finance and Management |

| Virginia |

The Commonwealth Institute |

The Commonwealth Institute |

| Washington |

None |

None |

| West Virginia |

West Virginia Office of the Governor |

Reuters |