BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) helps working families making low wages meet basic needs, but the new federal tax law will erode the credit’s value over time. Since all but one of the 29 states (and the District of Columbia) with state-level EITCs link their credits to the federal one, state EITCs also will lose value over time. The hit to both the federal and state-level EITCs represent a double whammy for working families that will make it harder for them to get ahead.

The federal tax law changed the way the tax code measures inflation. Because the new measure (known as the “chained” Consumer Price Index) grows more slowly than the old measure, the maximum value of the federal EITC also will rise more slowly.

This change erodes the maximum value of state EITCs, too, because 28 states plus the District of Columbia set their credits as a percentage of the federal one, and most states’ tax systems also adhere broadly to the federal inflation adjustment. (One state — Minnesota — sets the credit as a percentage of income and uses its own inflation adjustment.) As a result, just under 11 million working households will have less money to make ends meet, provide for their children’s needs, and spend money in their local economies.

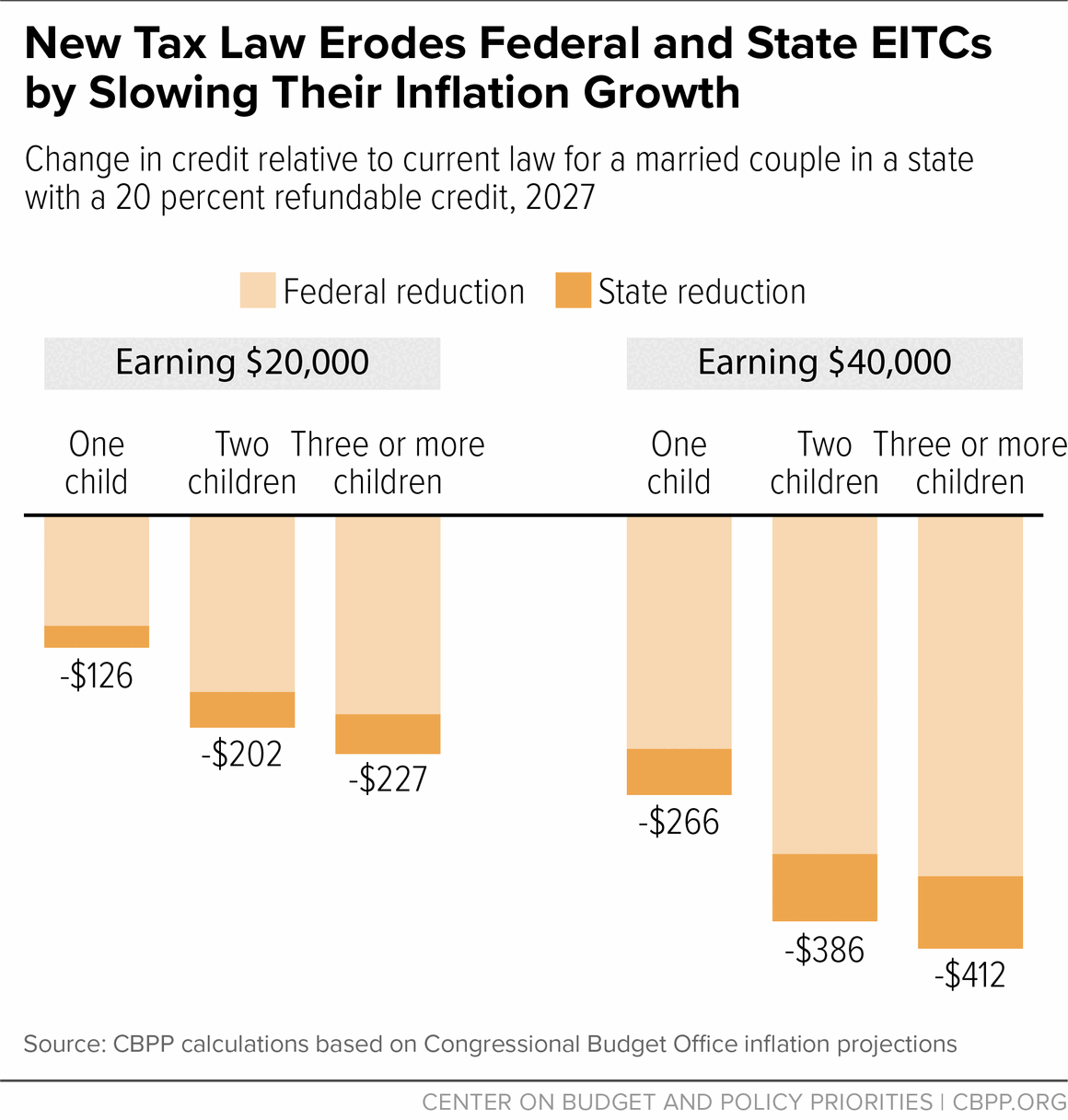

Consider a state that provides working families with a 20 percent refundable EITC. As the chart shows, a married couple with two children in that state making $40,000 would see their combined federal and state EITC shrink by $386 in 2027. At that same income, credits for families with three or more children would fall even more. (Twenty-three states and the District of Columbia now provide fully refundable credits of 3 to 40 percent of the federal credit. The other six state EITCs are available only to the extent that they offset a family’s state income tax).

This harm to low-paid working families stands in sharp contrast to the large tax cuts that the tax law bestowed on the wealthy and profitable corporations. In 2025, the year the tax cuts are fully phased in, the tax cuts will average $61,000 for top 1 percent and $252,000 for the top one-tenth of 1 percent — while the federal and state EITCs for low-income working families will have eroded in value.

States can make up for that erosion by continuing to expand their EITCs, which are a proven investment in working families. States that have cut or eliminated their credits should reverse course, and those that have limited their credits so that they only offset income taxes should expand them to help offset the full range of state and local taxes that low-income households pay.

All told, states should consider adopting an EITC if they don’t have one, expanding an existing credit, or enacting incremental increases over time to at least partially offset the loss in value in both the federal and state credits.