BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The IRS didn’t collect billions of unpaid employment taxes due to inadequate funding for a key compliance program, a new report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) finds. It shows that deep IRS funding cuts over the last decade have weakened the agency’s ability to perform its core functions: collecting taxes and enforcing tax laws. As policymakers set next year’s IRS funding, they should at least match — and preferably exceed — the House-approved $567 million boost in IRS enforcement and operations support.

TIGTA’s report focuses on an IRS program that identifies businesses that don’t file required returns and requires them to pay employment taxes, such as income and payroll taxes that they withheld on behalf of their employees. Staff time for the program plummeted by 84 percent between 2013 and 2017 due to the sharp drop in total IRS enforcement resources, TIGTA found. The report also found that if the program received adequate staffing and focused on higher-earning businesses, it could have collected at least $3.3 billion more in employment tax revenue over that period. Notably, the IRS agreed with TIGTA’s assessment that it should boost staff time on the program if “additional resources . . . become available.”

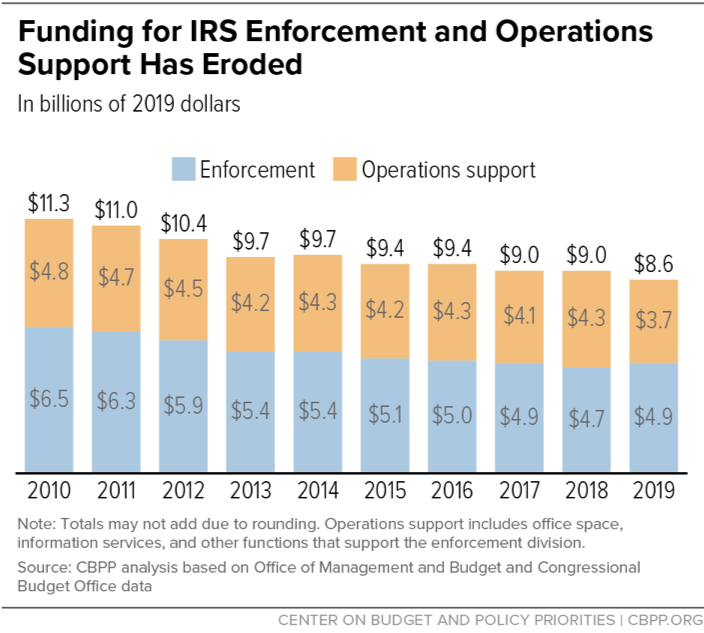

TIGTA’s findings, which highlight only a small share of the cost of weakened IRS enforcement, reflect a broader trend. Since 2010, policymakers have slashed funding for IRS enforcement and operations support (which includes functions that support the enforcement division) by roughly one-quarter in inflation-adjusted terms (see chart). The enforcement and operations support divisions have lost 28 percent of their workforce.

“There is a significant financial cost to underfunding the IRS and reducing its staff,” observed former IRS commissioner John Koskinen. Indeed, as the number of revenue officers investigating employment tax noncompliance has fallen, so has the number of penalties assessed for unpaid employment taxes. Similarly, the number of cases referred for criminal investigation has fallen by a third.

Our tax system is based on voluntary compliance, which requires both a high level of societal trust that the IRS is enforcing the tax laws fairly and effective enforcement itself. Compliance can fall as enforcement weakens: TIGTA notes that “[a]s more taxpayers experience little to no consequences for non-filing, the long-term impacts may include potential erosion of the voluntary compliance rate.”

Rebuilding IRS enforcement will require a multi-year funding commitment because the IRS must hire and train a significant number of auditors and other staff, which requires time and some funding certainty. As we’ve written, a reasonable initial goal would be to return IRS enforcement to the inflation-adjusted 2010 funding level over the next four years. That would mean raising funding (relative to the 2019 level) by $970 million per year in each of the next four years for enforcement and operations support accounts.

The Senate Appropriations Committee approved an IRS funding bill last month that raises enforcement and operations support by only $198 million over 2019 levels — far short of the House-approved $567 million increase. With annual increases at the Senate rate, it would take around two decades to reach the inflation-adjusted 2010 funding level. The Senate should therefore seek to boost funding further in its bill, and the final funding figure should at least match the House levels for enforcement and operations support.