BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The House plans to vote today on a bill to significantly expand the Research and Experimentation (R&E) tax credit and make it permanent. The White House threatened yesterday to veto the bill — and with good reason.

The R&E credit is one of the biggest “tax extenders,” a set of tax breaks (mainly for businesses) that policymakers routinely extend for a year or two at a time. The House bill expands the credit — likely making it twice as generous — and makes it permanent, without offsetting any of the $177 billion cost over the next decade.

The bill is the latest part of an effort by House Republican leaders to make the extenders permanent without offsetting their cost. Doing so is expensive, wrongly favors corporate tax breaks over tax credits that help millions of low- and moderate-income working families, and biases tax reform against reducing deficits.

That’s why policymakers should reject the R&E bill, regardless of whether they support making the R&E credit permanent on policy grounds. For example, President Obama’s 2016 budget expands and makes permanent the current R&E credit (and offsets the cost), yet he opposes the House bill.

More broadly, the House approach of making the extenders permanent without paying for them represents ill-advised fiscal policy and misplaced priorities. It would:

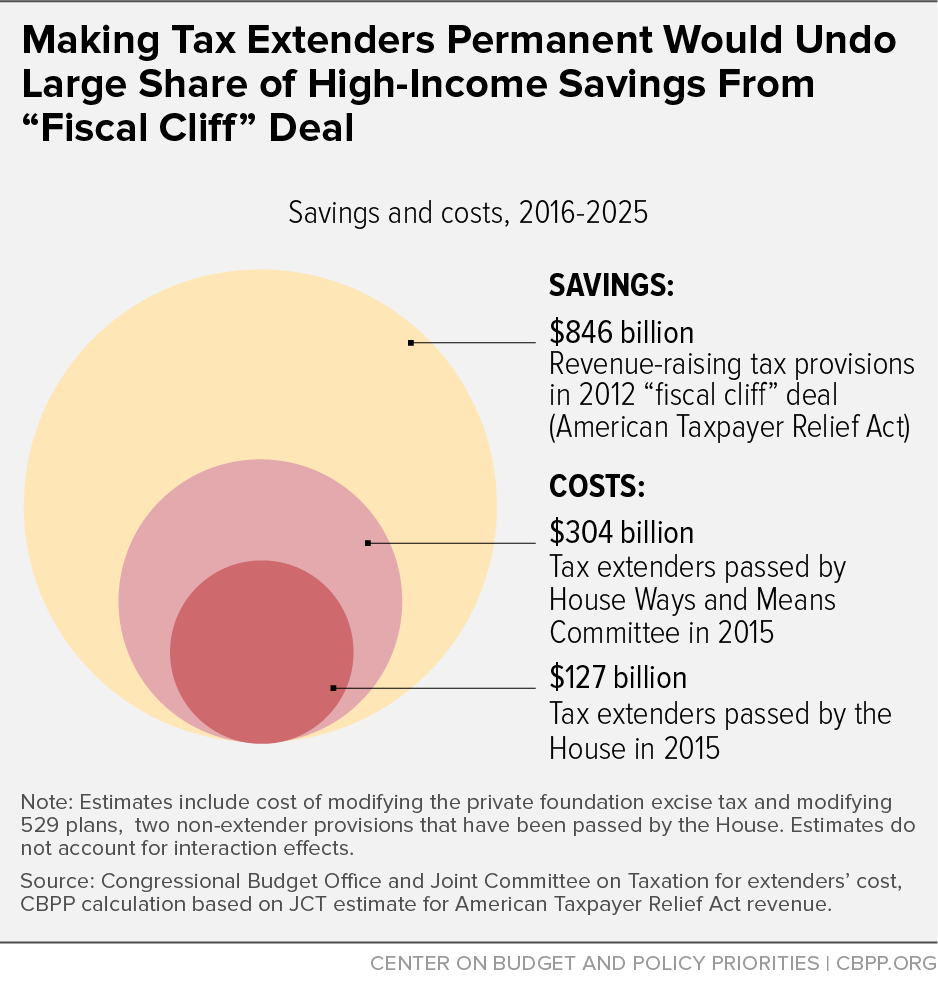

- Undo most of the savings from recent deficit-reduction legislation. The House last year passed a series of permanent tax-extender bills, along with a bill to expand and permanently extend the “bonus depreciation” tax break, which together would have cost nearly three-quarters of the revenue raised by the 2012 “fiscal cliff” legislation. The House has begun this process anew this year, passing bills to make eight tax provisions permanent at a ten-year cost of $127 billion. Expanding and making permanent the R&E credit would bring the total cost of House-passed bills this year to $304 billion (see chart).

-

Place the tax extenders ahead of other, more critical tax provisions scheduled to expire in coming years. These include key elements of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC) for low-income working families. If those measures expire, more than 16 million people in low-income working families, including 8 million children, would fall into — or deeper into — poverty. And some 50 million Americans would lose part or all of their EITC or CTC. A growing body of evidence links income from these tax credits to improvements in children’s health, educational attainment, and employment and earnings later in life.

- Bias tax reform against reducing deficits. Policymakers are expected to consider corporate tax reform this year. If they make the extenders permanent in advance of tax reform, a reform plan would no longer have to offset the extenders’ cost to achieve revenue neutrality. This would free up hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue-raising provisions over the decade that policymakers could then use to offset the cost of lowering the corporate tax rate more sharply or closing fewer dubious corporate tax breaks, while still claiming revenue neutrality.