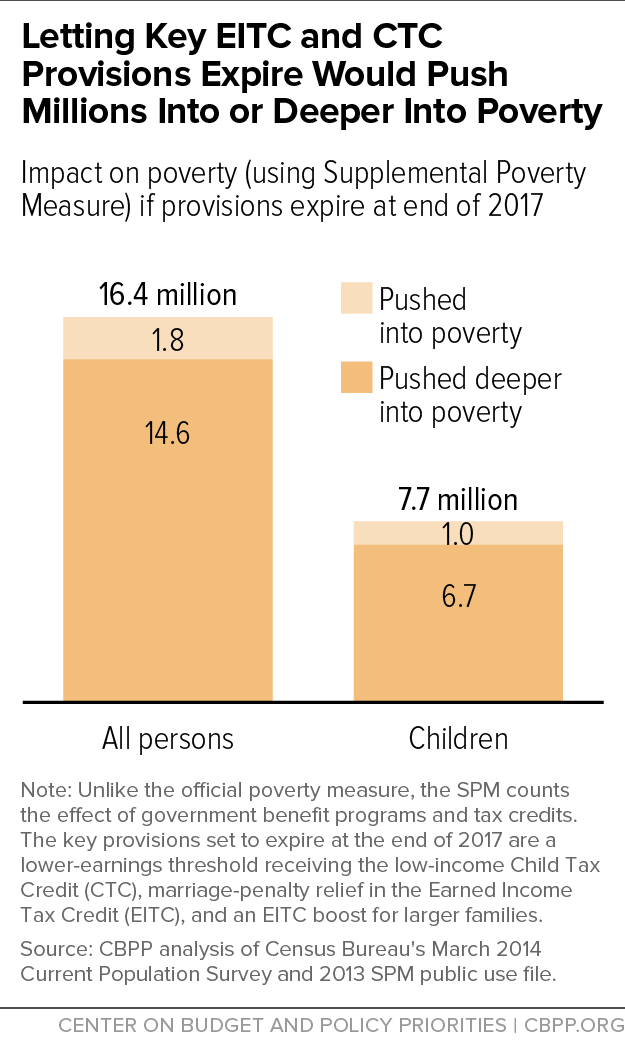

16 Million People Will Fall Into or Deeper Into Poverty if Key Provisions of Working-Family Tax Credits Expire

Congress Must Act to Save Key Provisions

End Notes

[1] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Making the EITC and CTC Expansions Permanent Would Benefit 13 Million Working Families,” February 20, 2015, http://ctj.org/pdf/ctceitcreport2015.pdf.

[2] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon DeBot, “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated April 3, 2015, http://bit.ly/1NupNqR.

[3] Arloc Sherman, et al., “Pro-Work Tax Credits Help 2 Million Veteran and Military Households,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 30, 2015, http://bit.ly/1BUqj0E.

[4] Bryann DaSilva, et al., “Pro-Work Tax Credits Help 4.8 Million Rural Households,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 24, 2015, http://bit.ly/1fExYpi.

[5] Bryann DaSilva, Arloc Sherman, and Chye-Ching Huang, “14 Million Millennials Benefit From Pro-Work Tax Credits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 12, 2015, http://bit.ly/1R0A0MF.

[6] CBPP analysis of Treasury Office of Tax Analysis estimates and the Census Bureau’s March 2014 Current Population Survey.

[7] The American Opportunity Tax Credit (which is not the subject of this paper), a partially refundable credit that helps defray college costs, is also set to expire at the end of 2017 and should be made permanent. If it expires, it will be replaced by the non-refundable Hope Credit, which has a lower maximum value ($1,800 instead of $2,500) and is available for fewer years of study (up to two years instead of four). If the AOTC expires, about 11 million mostly middle-class families will lose some or all of the tax credits they would otherwise receive to help offset college costs.

[8] In 2015, the maximum EITC for families raising more than two children is $694 larger than the maximum EITC for families with two children. These maximum credit amounts are indexed for inflation, so the nominal dollar difference will widen modestly between now and 2017.

[9] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Making the EITC and CTC Expansions Permanent Would Benefit 13 Million Working Families,” 2015. See also Chye-Ching Huang, “What Would Congress’s Inaction Cost Working Families? Find Out.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 8, 2014, http://bit.ly/1rXoOq1 for an interactive calculator of the impact if the provisions expire.

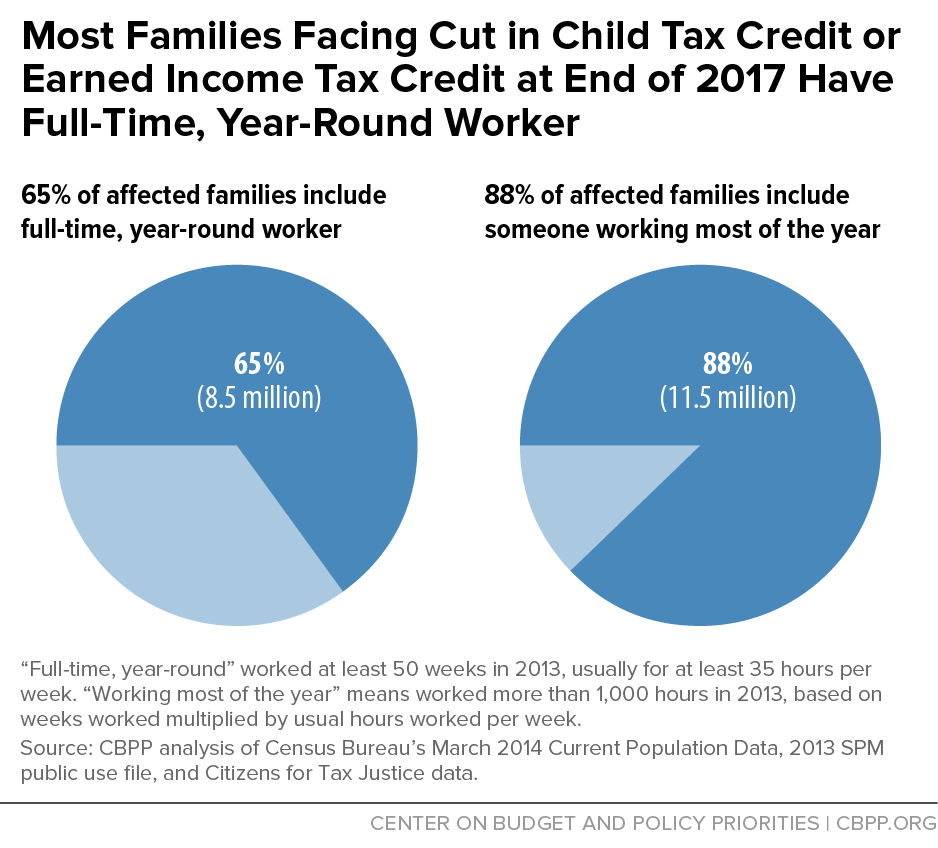

[10] CBPP analysis of Census Bureau’s March 2014 Current Population Survey and CTJ estimates.

[11] About 3.6 million families — including 5.0 million children — will lose their entire CTC, while an additional 5.6 million families — including 10.2 million children — will lose part of their CTC. About 6.3 million families, including 14.7 million children, will lose part or all of their EITC. Estimates from CBPP analysis of data from CTJ, using totals from “Making the EITC and CTC Expansions Permanent Would Benefit 13 Million Working Families,” February 20, 2015, http://ctj.org/pdf/ctceitcreport2015.pdf and the proportion of families and children losing the CTC from “The Debate over Tax Cuts: It’s not Just About the Rich,” July 19, 2012, http://ctj.org/pdf/refundablecredits2012.pdf.

[12] CBPP analysis of Census Bureau’s March 2014 Current Population Survey and 2013 SPM public use file.

[13] Arloc Sherman, et al., “Pro-Work Tax Credits Help 2 Million Veteran and Military Households.”

[14] Bryann DaSilva, et al., “Pro-Work Tax Credits Help 4.8 Million Rural Households.”

[15] Bryann DaSilva, et al., “14 Million Millennials Benefit From Pro-Work Tax Credits.”

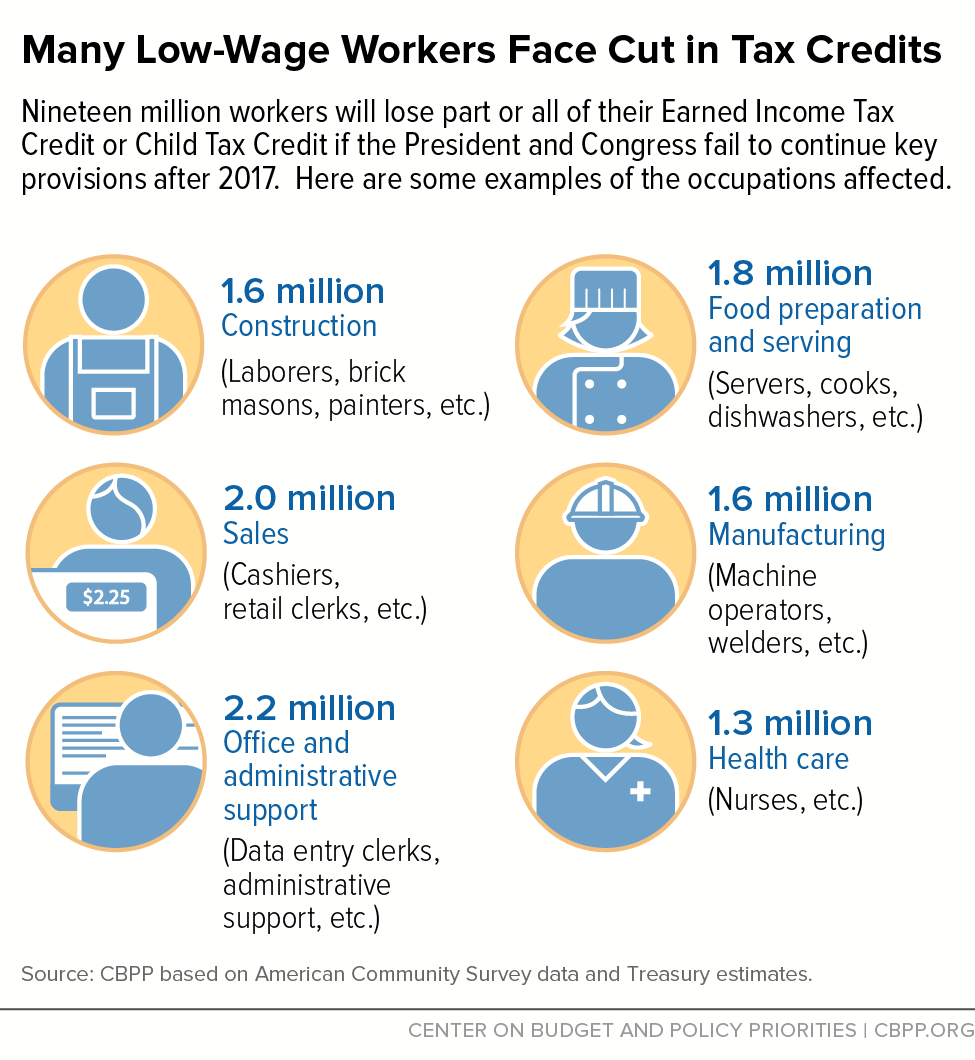

[16] Chuck Marr, Vincent Palacios, and Bryann DaSilva, “Saving Key Provisions of Pro-Work Tax Credits Would Help Wide Range of Low-Wage Workers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 27, 2015, http://bit.ly/1LAFvkI.

[17] Ibid.

[18] CBPP analysis of Census Bureau’s March 2014 Current Population Survey.

[19] CBPP analysis of Treasury Office of Tax Analysis estimates and the Census Bureau’s March 2014 Current Population Survey.