BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Connecticut Capital Gains Surcharge Would Raise Needed Revenue, Narrow Inequality

To their credit, Connecticut lawmakers are considering a proposal to levy a modest 2 percent surcharge on capital gains of the wealthiest taxpayers, which would raise needed revenue, reduce inequality, and help the state’s economy.

Relatively few, mostly white, families hold an overwhelming share of the nation’s wealth, leaving millions of others, including those of color, with less wealth and fewer opportunities than they’d otherwise have. But states can build more broadly shared prosperity by strengthening taxes on wealth, including capital gains.

Capital gains are the profits an investor realizes when selling an asset that has grown in value, such as stock, mutual funds, real estate, or artwork. In Connecticut, a capital gains surcharge on individuals with incomes above $500,000 and couples with incomes above $1 million would help in three ways:

First, it would raise $262 million annually in much-needed revenues.

Connecticut faces a projected $3 billion deficit in the upcoming biennial budget. The state has squeezed programs and services since the Great Recession, cutting medical care for low-income adults, reducing the state’s earned income tax credit that goes to low-income working families, and cutting support for colleges and universities. Additional cuts that reduce incomes for families in the state, harm its schools, or weaken its infrastructure will further dampen Connecticut’s future economic growth.

Second, it would reduce inequality and improve the state’s upside-down tax system.

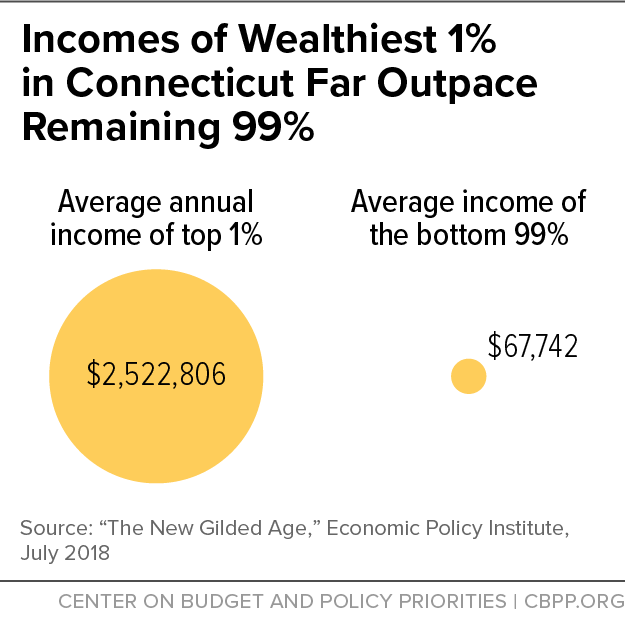

Income inequality in Connecticut is the third highest among all states, with the wealthiest 1 percent earning average incomes almost 40 times those of the bottom 99 percent (see chart). Families in the bottom and middle have faced the highest barriers to recovery since the Great Recession. Between 2009 and 2015, the top 1 percent captured 134 percent of the total income growth in the state while income of the rest dropped.

Connecticut’s upside-down tax system worsens this imbalance because it takes a much higher share of income from low- and moderate-income families than from wealthy families. The lowest- and middle-income taxpayers face a tax rate some 50 percent higher than the wealthiest taxpayers, on average.

Third, it would boost Connecticut’s economy.

Taxes on the highest incomes can generate substantial revenue for public investments that boost a state’s productivity in the long run, evidence suggests, without harming economic growth in the short term, as our recent report showed.

In six of eight states (including Washington, D.C.) that enacted millionaires’ taxes since 2000, private-sector economic growth has met or exceeded that of neighboring states since those states enacted their tax increases. Seven of the eight states have had per capita personal income growth at least as strong as nearby states, and five of the eight have added jobs at least as quickly as their neighbors. (While Connecticut is the exception — it raised its state income tax rates and saw markedly weaker growth than its neighbors — that was likely for reasons other than state tax levels, as we’ve explained.)

And tax increases on the wealthy can generate substantial revenues for investments in people and communities that provide long-term economic and social benefits. For example, raising personal income tax rates has enabled states to prevent or minimize harmful budget cuts or invest in ambitious new initiatives such as expanding early education, boosting access to college, improving infrastructure, and strengthening “rainy day” funds to prepare for the next recession. Tax differences between states, including differences in personal income tax rates, only minimally affect state economic growth, research generally finds.