BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit Lifted 10.6 Million People out of Poverty in 2018

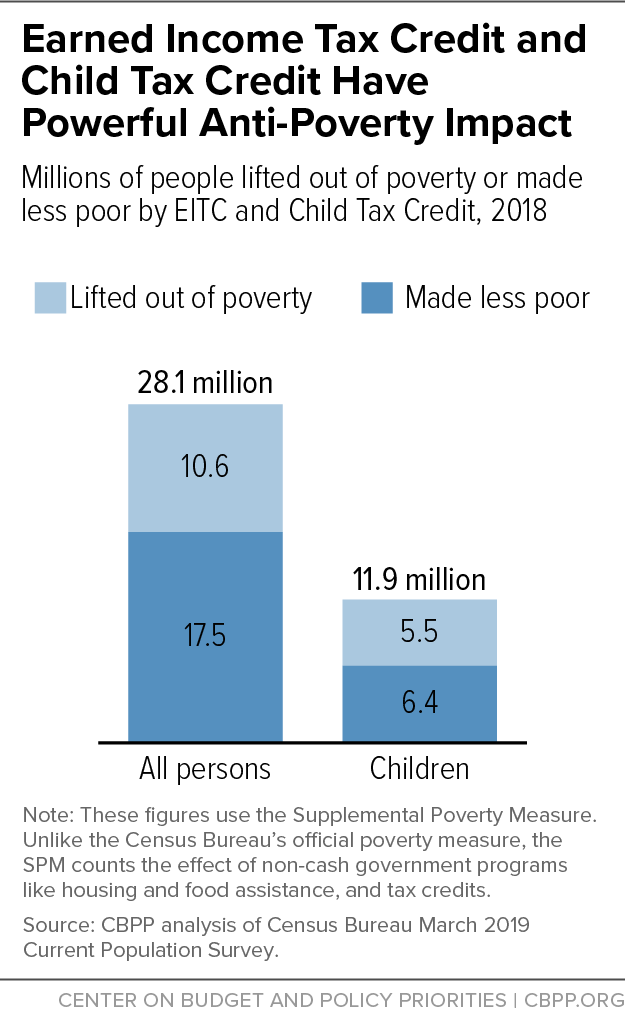

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit together boosted the incomes of 28.1 million poor Americans in 2018, lifting 10.6 million above the poverty line and making 17.5 million others less poor, our analysis of new Census data shows. These totals include 11.9 million children, 5.5 million of whom were lifted out of poverty and another 6.4 million made less poor. The figures use the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, which — unlike the official poverty measure — accounts for taxes and non-cash benefits as well as cash income.

The Census estimates also don’t account for the impacts of state EITCs that 29 states and the District of Columbia provided in 2018. These state credits build on the success of the federal credit, further reducing poverty and inequality. (Puerto Rico also has its own EITC as of 2019.)

A growing body of research links these tax credits to better infant health, improved school performance, higher college enrollment, and projected increases in earnings in adulthood. As a result, the tax credits may reduce poverty not only in the near term, but also in the next generation.

These figures are for 2018 and therefore are the first to account for the 2017 tax law, which took effect in 2018. But that law affected poverty only “marginally,” according to the Congressional Research Service. While it doubled the Child Tax Credit’s maximum value from $1,000 to $2,000 per child, it denied more than 26 million children in low- and moderate-income working families the full $1,000 credit increase, with families that include 11 million children receiving only a token increase of $75 or less.

More troubling for many families is the law’s provision ending the Child Tax Credit for about 1 million children lacking a Social Security number. This group overwhelmingly consists of so-called “Dreamers” — young people with undocumented status who were brought to the United States by their immigrant parents.

The 2017 law also erodes the value of the EITC for millions of working-class families over time. It switches from the regular Consumer Price Index (CPI) to the “chained” CPI to adjust tax brackets and certain tax provisions for inflation each year. Since that index rises more slowly over time than the regular CPI does, the maximum EITC will also rise more slowly.

Overall, the 2017 tax law is heavily tilted toward the nation’s highest-income people and largely ignores a wide swath of low-wage workers who struggle to meet their families’ basic needs. Policymakers should restructure it, and when they do, they should make improving the EITC and Child Tax Credit top priorities of any such effort.