- Home

- How Should States Respond To Recent Fede...

How Should States Respond to Recent Federal Tax Changes?

Many states expect to see a change in revenues due to the major federal tax legislation enacted last December. States should respond with substantial caution to the possibility of a revenue boost and focus their response on preparing for potential cuts in federal funding for states, as well as the next recession. They also should strongly consider raising revenue from corporations and other wealthy interests that just received a large federal tax break in order to invest in stronger education systems, more efficient transportation networks, and other public services that undergird broadly shared prosperity.

Some have called for states to cut taxes, claiming that most states will see revenue “windfalls” thanks to the federal changes. That’s overstated. Roughly 29 states will lose revenue, see no impact, or see modest revenue gains totaling less than 1 percent of general fund revenue, Roughly 29 states will lose revenue, see no impact, or see modest revenue gains totaling less than 1 percent of general fund revenue. according to early estimates. And in many of those states that could see larger revenue boosts, the added revenue would come disproportionately from lower-income families (due to the elimination of the states’ personal exemptions), which would partially reverse states’ substantial progress in recent decades in eliminating income taxes for families in poverty. At least some of these states are unlikely to allow this to occur.

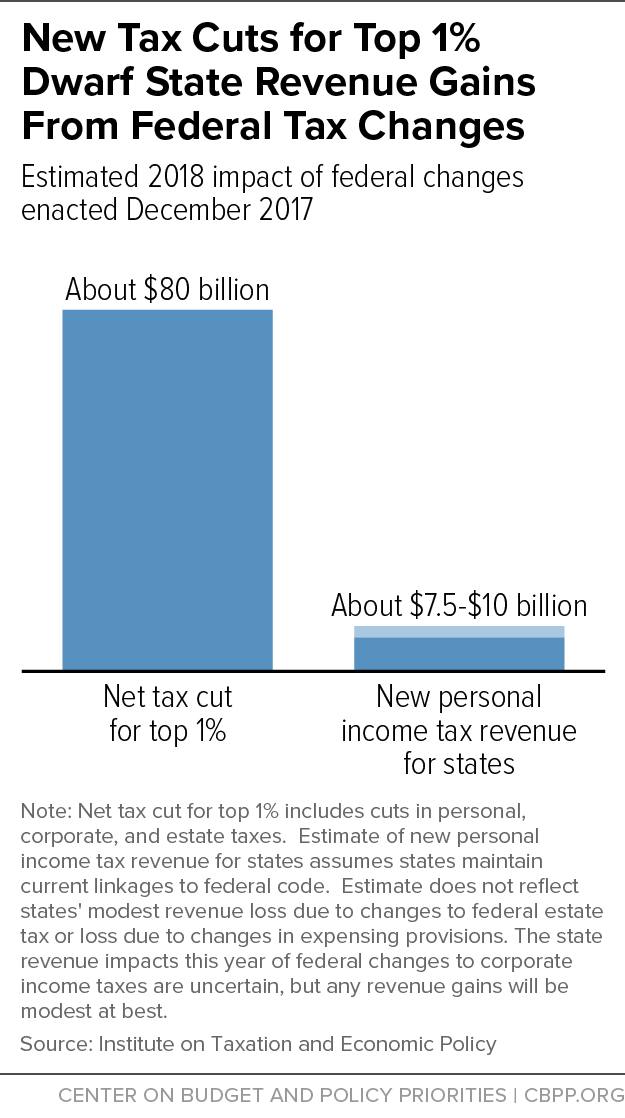

The real windfall from the federal changes will go to corporations and the highest-income households, whose annual tax cuts will vastly exceed any revenue gain for states. States’ revenue gains — in the aggregate — will also be much smaller as a share of their revenue than what they received from the last major federal tax overhaul, in 1986.

Further, while the large tax cuts for corporations and wealthy households are a certainty, state revenue gains are highly uncertain. One reason is that tax lawyers and accountants will likely find new loopholes to open and exploit in the hastily written federal law, at the expense of states and the federal government. Also, the state revenue impacts of some potentially costly new federal provisions — including the shift to a “territorial” corporate income tax and the expanded definition of education spending eligible for tax breaks through so-called “529” savings plans — are very difficult to estimate. Taxpayers’ behavioral responses to the law are also uncertain; for example, more workers may become independent contractors in order to take advantage of the new tax break for “pass-through” entities. And some state statutes are open to interpretation about whether particular state provisions link to the federal code, so state interpretations (and court rulings on any ensuing legal challenges) will affect the revenue impact.

Given these uncertainties, states should react cautiously to any projected gains in revenue and respond to the federal tax changes — which are heavily skewed to wealthy households — with prudence and, when possible, in ways that help a broader group of Americans get ahead. States should:

- Build up their reserves to prepare for potential cuts in federal support for states and for the next recession. States would be wise to build up their reserves rather than spend revenue boosts from the federal changes on tax cuts or major spending increases. Republican congressional leaders and the President have made clear their interest in substantially cutting Medicaid and various other forms of federal support for states and localities. The federal tax changes, by substantially increasing the federal debt, may add to pressure for such cuts in the next few years. Further, a recession does not appear imminent but will inevitably occur at some point in coming years; the current expansion is already the second longest in American history.

- Avoid income tax rate cuts. Some state policymakers are responding to initial projections of revenue gains by proposing income tax rate cuts, whose cost in some cases would far exceed the projected revenue. These proposals would hamper a state’s ability to address potential cuts in federal aid and other looming budgetary challenges. They also would further widen inequality, since rate cuts typically benefit the wealthy more.

- Retain state personal and dependent exemptions. In some states, the loss of federal personal exemptions could result in the loss of state-level personal or dependent exemptions, raising revenue in a way that would fall hardest on lower-income families. These states should first carefully examine their statutes to determine whether they would lose their personal exemptions. If the exemptions would in fact disappear, these states should take the necessary legislative steps to retain them, rather than use up the regressive revenue gains through new tax cuts or spending increases. States may also wish to consider converting their exemptions to credits, which would help lower-income families more as a share of their income.

- Decouple from provisions that weaken state revenue systems. States also should take the necessary steps to avoid losing substantial revenue due to the federal tax changes, especially given the challenging fiscal environment in which they operate. For instance, states whose tax codes are coupled to the federal standard deduction, which has doubled, may wish to consider retaining their current standard deductions. States also should consider retaining their current rules for expensing equipment and machinery purchases (given the revenue impact of federal changes in this area) and retaining their current exemption amounts for estate taxes.

- Consider raising revenue from corporations and the wealthy. The federal tax law’s extraordinary windfall for corporations and very high-income households will further concentrate income and wealth at the top. States may wish to distance themselves from this approach, offsetting some of the windfall for those at the top through tax increases and by investing the revenue in middle- and lower-income Americans. For instance, states could seek to recoup in whole or part the misguided federal tax cut for “pass-through” businesses, to close corporate loopholes expanded by the new law, or to raise top income tax rates.

- Consider SALT “workarounds” as part of broader plan. Some high-income states with a disproportionately large share of taxpayers affected by the new $10,000 cap on state and local tax deductions (SALT) are investigating ways to restructure their tax codes to protect taxpayers from the cap. States heavily affected by the SALT cap should give such “workarounds” thoughtful consideration — and should do so as part of a more comprehensive response to the law’s effects.

Provisions of Recent Federal Tax Legislation That Most Affect State Revenues

The legislation President Trump signed December 21 made numerous changes to the federal tax code, many of which affect state revenues because of how states link to the federal code. Changes in federal income tax rates do not affect state revenues, but changes to the base of federal income taxes often do. The most important provisions of the new federal law in terms of their impact on state revenues include:

- Elimination of personal exemptions. This federal change expires after 2025, after which personal exemptions are restored.

- Doubling of the standard deduction. This change also expires after 2025.

- Limit on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction. This change limits taxpayers to $10,000 in federal tax deductions for their combined state and local property and income taxes (or sales taxes in lieu of income taxes). This expires after 2025.

- Changes to other itemized deductions. The new tax law lowers the cap on deductible mortgage interest, eliminates the Pease phase-out of itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers, and lowers the threshold for deducting high medical expenses. These changes will expire in coming years.

- New “pass-through” deduction. The tax law creates a new 20 percent deduction on income from pass-through businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships that business owners claim on their individual tax returns. It contains some restrictions on the type of pass-through income that is eligible for the deduction. This expires after 2025.

- Full expensing. This change allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of machinery and equipment, rather than depreciating it over time. It will be in place through 2022 and then phase out through 2027.

- Shift to a “territorial” corporate income tax and new “repatriation” tax. These aspects of the tax law exempt U.S.-based multinational corporations from paying U.S. corporate taxes on their foreign profits, rather than requiring payment when companies “repatriate” their profits to the United States, as under current law. They also subject to immediate taxation (albeit at sharply reduced rates) the large amount of cash held by the foreign subsidiaries of U.S. corporations.

- Expansion of the corporate income tax base. Various measures in the new law eliminate the domestic production deduction that reduces taxes for manufacturers and from which many states have never decoupled, and place new limits on the ability of corporations to deduct interest expenses and to use losses to offset prior-year and subsequent-year profits.

- Estate tax cut. The new law doubles the value of estates that is exempt from the estate tax — from $11 million per couple ($5.5 million per person) to $22 million per couple ($11 million per person). This expires after 2025.

- Repeal of Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate. The tax law permanently eliminates the requirement that most people get health insurance or pay a penalty.

State Income Tax Systems Link to Federal Code

In most states, the starting point for determining a person’s taxable income in the state is a line on his or federal tax form — usually federal adjusted gross income (AGI), but federal taxable income in some states. A handful of states use neither of these starting points but link to the federal code in other ways. Indeed, beyond the starting points used for determining taxable income, each state links to the federal code in its own, idiosyncratic way. From standard deductions to personal exemptions to various other deductions, credits, and exemptions, states have a multiplicity of choices about how and when to link to the federal code, and states have made these choices in a variety of ways.

When the federal code changes, as it did in dramatic fashion under legislation enacted in December, state codes may or may not automatically change depending on how the state links to the federal code. Some states use “rolling” conformity with the federal code. That is, their codes automatically conform with changes in the federal code unless the state takes legislative action to “decouple” from the federal changes to certain provisions. Other states use “fixed date” conformity, meaning that they conform with the federal code as of a specified date, which they periodically or annually move forward. If these states wish to decouple from particular changes in federal law, they can do so when they move the conformity date forward.

Sometimes the precise relationship between a state’s income tax code and the federal one is open to interpretation. State statutes sometimes are not clear about the relationship, especially when the federal tax code changes in unanticipated ways, as under the recent federal tax bill.

State Revenue Impacts: Mixed, Relatively Modest, Uncertain

Claims that most states will receive a “windfall” from the recent federal tax changes due to their tax codes’ interaction with the federal one are overstated. At least some states will lose revenue, and most states will see modest revenue gains at best, according to early estimates. The real windfall from the recent federal tax law will go to corporations and the highest-income households, whose annual tax cut will vastly exceed any revenue gain for states.

Further, while tax cuts for corporations and wealthy households are certain, the state revenue impacts are highly uncertain and could prove more negative than initial estimates suggest. And in most states with the biggest gains, the new revenues will come disproportionately from low- and modest-income families, exacerbating the federal tax changes’ harmful effects on inequality.

Revenue Gains Will Be Small Compared to 1986 and to Windfalls for Top 1 Percent

The revenue implications for states vary substantially. Roughly eight states will lose revenue, even before taxpayers and corporations uncover new loopholes and ignoring other downside risks, unless they take steps to avoid the damage. Another dozen states will see no effect, at least on the personal income tax side, either because they lack a broad-based income tax or because their tax codes do not conform to major provisions of the federal personal income-tax code. About nine additional states will see modest gains equal to less than 1 percent of state general funds. In total, about 29 states will see modest revenue gains, at best, according to these early estimates.[1]

The remaining states may see more sizeable revenue gains if they retain their current connections to the federal code, though the magnitude is highly uncertain, as described below. Further, in many of the states with the biggest gains, much of the new revenue would come from eliminating personal exemptions, a tax increase that would hit lower-income families hardest and thereby reduce gains that states have made over the last few decades — under both Republican and Democratic administrations — in cutting income taxes on the working poor.[2]

While the state revenue impact is highly uncertain, there’s no question that net revenue gains for states overall will be much smaller than their gains from the last major federal tax overhaul, in 1986. Projections at that time estimated that in the median state gaining revenue from the personal income tax changes, the gain would equal 11 percent of state personal income tax revenues.[3] This time around, very few states are likely to see gains of that magnitude, perhaps only three (most likely Louisiana, Maine, and Michigan).

There’s also little question that state revenue gains will pale in comparison to the windfalls that the richest households will receive in new federal tax cuts. The top 1 percent of households, whose annual income averages over $2 million, will get a net tax cut of about $80 billion this year, including personal and corporate income tax cuts, as well as estate tax cuts.[4] Even under generous assumptions, states will net in the neighborhood of $7.5 billion to $10 billion in new personal income tax revenue this year, based on estimates by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy — roughly one-tenth of the total windfall for the top 1 percent. (See Figure 1.) And state revenue losses from the higher federal estate tax threshold will modestly reduce those gains. The impact of corporate income tax changes on state revenues is uncertain, but any revenue gains this year from these changes will be modest at best.[5]

State Revenue Impacts Are Highly Uncertain

States should exercise substantial caution regarding estimates of the state revenue impact of the federal tax changes. Those estimates are highly uncertain and may well prove optimistic, for the following reasons:

- Revenues may decline as taxpayers find loopholes in the new federal law. The federal tax changes were rushed through Congress so quickly that large segments of the new law were hastily written, with little input from tax experts and others affected by the changes. Taxpayers and professional tax preparers will likely find new loopholes to exploit, reducing their tax liability at the expense of states and the federal government.[6]

- Some provisions are very difficult or impossible to model. State budget analysts will find it extremely difficult to estimate with any precision the state revenue effects of some provisions of the new federal tax law. Further, the more consequential of these provisions carry significant downside risk for state budgets. Examples include:

- The shift to a “territorial” corporate income tax likely will drive more corporate profits into overseas tax havens where they can accrue tax-free, lowering corporate tax revenue in many states. The magnitude and timing of these effects are uncertain.

- The new federal code allows businesses to expense the full cost of equipment purchases immediately rather than gradually over its useful life. That change will reduce federal and state revenues in the next few years, but how much individual states will lose is very difficult to know. States will recoup the lost revenue in later years because companies will no longer be depreciating earlier purchases, but in the next few years, states will lose an uncertain amount of revenue.

- The federal tax changes include an expansion of the allowable uses of funds from tax-advantaged “529” education accounts. States will lose revenues as a result, but again the magnitude and timing of the loss are very difficult to estimate.

- Behavioral responses are uncertain. The major changes in the federal tax code likely will cause taxpayers to change their behavior to reduce their tax bills in new ways now allowed under the federal code, reducing both federal and state revenue. For instance, some workers may shift their status from “employee” to “independent contractor” to take advantage of new, lower tax rates for independent contractors organized as “pass-through” business entities. Given the breadth of the changes, these behavioral responses could be extensive, but no one knows at this point.

- State statutes are open to interpretation. Sometimes, the state statute that determines whether and how particular provisions in a state’s code link to the federal code is ambiguous. For instance, several states have statutes that could be read to require taxpayers to receive a federal personal exemption to qualify for the state’s personal exemption. The ultimate state revenue impacts of the new law will hinge in part on how states interpret their statutes and on the results of any legal challenges that ensue.

To be sure, some of the federal tax changes will likely raise state revenue. The new rules around “repatriating” corporate profits, for instance, could result in higher revenues in some states. However, the chances are slim that states will see a revenue boost in the near future, as corporations would likely fight in court any state attempt to tax repatriated income. Most of the major provisions whose revenue impact is particularly uncertain carry downside, not upside, risks. That is, it is more likely that revenue-gaining provisions will generate smaller revenue gains than expected and that revenue-losing provisions will lose more revenue than expected, rather than the other way around.

Some proponents of the federal tax changes claim they will cause a surge in economic growth, raising state and federal revenue. States shouldn’t bet their future fiscal health on this dubious, highly contested prediction. Separate, nonpartisan estimates that the Tax Policy Center, the Penn Wharton Budget Model, and the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation made of bills similar to the December legislation — which take into account any positive economic effects from the bills as well as negative economic effects from the resulting increase in the national debt — find the effects on economic growth are small at best, adding less than one-tenth of one percentage point to annual economic growth over the next ten years.[7]

How Should States Respond?

Some state policymakers have overreacted to the possibility of new revenue by proposing major income tax rate cuts, even cuts whose cost would exceed the highly uncertain estimate of new revenue. For instance, Idaho Governor Butch Otter proposed personal and corporate income tax rate cuts and other cuts totaling about $200 million annually after the state projected that revenues would rise by nearly $100 million due to the federal changes.[8]

Given the substantial uncertainty around the ultimate revenue impact, states should respond cautiously. They also should be prudent because new threats to their fiscal stability loom, including the potential for cuts in federal aid for states and localities and the inevitability of another recession.

In addition, many states lack sufficient revenues to make the new investments in people and infrastructure required for an economy in which prosperity is broadly shared. At least 30 states closed budget shortfalls this year or last year, the most since the aftermath of the Great Recession.[9] States may need to raise new revenue to improve the productivity of their workforces, encourage entrepreneurship, and strengthen the physical infrastructure that undergirds private enterprise. At the least, states should avoid cutting income tax rates, which would further enrich the highest-income households even as — in most states with the biggest revenue gains — the added revenue will come disproportionately from low- and modest-income families.

Build Up Reserves to Prepare for Potential Federal Cuts and for Next Recession

States would be prudent to save at least a substantial share of the revenues they receive. Many already struggle to meet their current needs, and significant new threats loom, including:

- Potential cuts in federal aid to states and localities. Republican congressional leaders and the President have made clear their interest in cutting federal support for Medicaid and other federal funding for services and programs delivered by states and localities. The budget resolution that Congress passed in October 2017, which jumpstarted the tax legislation, called for $5.8 trillion in budget cuts over the next decade, with large cuts in Medicaid, Medicare, SNAP (formerly food stamps), and non-defense discretionary (NDD) funding, the part of the federal budget that includes funding for a wide range of state and local services, including K-12 education, environmental protection, affordable housing, and child care.[10]

It’s now unlikely that significant NDD cuts will occur in the 2018 election year, or perhaps in 2019 either. But the longer-term trend in federal NDD funding is downward, both in inflation-adopted dollars and as a share of the economy. This trend is likely to continue, given both the new tax law’s shrinkage in federal tax revenue and the rising health care and retirement costs associated with the aging of the population.

- The next recession. While a recession does not appear imminent, the current expansion is the second longest in American history, and in a few months will be the longest. Given this and the impossibility of predicting when the next recession will hit, states would be wise to prepare for it. The typical state ended the last fiscal year with a balance of 8 percent of the budget, less than states had heading into the last recession and far less than they need in a typical recession. The average state would require reserves of at least 15 percent of its annual budget to weather a moderate recession without significant spending cuts or tax increases; only seven states ended last year with reserves of that size.

Retain State Personal and Dependent Exemptions

As noted, in most of the states with the biggest projected revenue gains, the new revenue would come disproportionately from lower-income households. In these states, the temporary loss of federal personal exemptions through 2025 under the new law may result (depending in some states on how they interpret their statutes) in the loss of state personal or dependent exemptions, raising state taxes on many people.

Personal exemptions are a flat dollar amount in all of these states. As a result, eliminating them raises taxes more on lower-income households, as a share of their income, than on higher-income households. And nearly all state and local tax systems already ask more of middle- and low-income households than of the wealthy (i.e., state and local taxes already consume a larger percentage of the incomes of low- and middle-income households than of affluent households). Eliminating personal exemptions thus would make state and local tax systems still more regressive.

Over the last three decades, many states, under both Republican and Democratic leadership, have made substantial progress in reducing taxes for families living in poverty.[11] It’s almost inconceivable that any state would allow its personal exemptions to simply disappear without taking steps to avoid raising taxes on working people with very low incomes. The most obvious solution is to simply delink their personal and dependent exemptions from the federal code, at least through 2025, after which federal personal exemptions will reappear under current law. States could also consider going a step further by restructuring their personal exemptions as refundable tax credits (if they aren’t structured that way already), with a goal of extending states’ gains in reducing or eliminating income taxes for the poor. (Tax credits, especially when they are “refundable” — available in full to all taxpayers regardless of tax liability — generally benefit lower-income families, as a share of their income, more than higher-income people.)

Avoid Income Tax Rate Cuts

Some states, including Maryland and Michigan, are considering cutting income tax rates in response to projected revenue gains from the federal tax changes. The Tax Foundation and other tax cut proponents argue that states should cut rates in response to their supposed “windfalls.”[12]

Responding to a tax hike that falls hardest on those with lower incomes by cutting income tax rates would be both inappropriate and harmful, since rate cuts typically benefit those with higher incomes the most. In effect, states would be raising income taxes for lower-income families and transferring the money to high-income families, even though income inequality already is at historically high levels and the recent federal tax changes primarily benefit the well-off.

Further, income tax rate cuts weaken state revenue systems at a time when states may face higher costs soon if federal aid declines further or when another recession strikes. Since income taxes are likelier than other major state revenue sources to keep up with the cost of state services over time, weakening them is particularly harmful to states, many of which already struggle with structurally inadequate revenue systems.

Decouple From Provisions That Weaken State Revenues and Fall Hardest on Poor

States whose tax codes conform automatically to federal changes (those with “rolling” conformity) often decouple their tax codes from the federal code in specific areas. And states with “fixed date” conformity can simply not conform their tax codes to specific changes to the federal code. That’s exactly what states should do when it comes to federal changes that would reduce state revenue or otherwise harm states or households with low or moderate incomes. Among the provisions states should consider rejecting are changes to:

- Personal exemptions. As noted, in some states, personal exemptions will disappear for the next few years because the new federal law eliminates federal personal exemptions until 2026. This would raise state taxes in a number of states. States should simply decouple from this federal change or, in fixed-date conformity states, decline to conform their codes to the temporary federal provision.

- Standard deduction. The new federal tax code doubles the size of the standard deduction. At least nine states and the District of Columbia link their own standard deduction to the federal one, so it, too, will double — costing the states substantial revenue — if they conform to this part of the new federal code. States should consider refusing to conform to the change in the federal standard deduction, to avert the revenue loss.

- Estate tax. The new law doubles the federal estate tax exemption to $22 million for a couple. Hawaii, Maine, and the District of Columbia use the federal exemption to administer their own estate taxes, so the state exemption will likely double automatically in these states unless they act to prevent that. The same will happen in Maryland in 2019, when that state’s exemption is scheduled to rise to match the federal exemption. These states should decouple from this unwarranted change.

- Expensing provisions. The new federal law allows businesses, in calculating their taxable income, to subtract from their gross receipts the total cost of machinery and equipment (and certain types of real estate and computer software) in the year in which it is placed in service (“full expensing”), rather than subtracting part of the cost each year over its useful life (“depreciation”). Full expensing is in place through 2022 and then phases out through 2027 under the new federal law, returning to normal depreciation schedules after that. The federal law also expands separate, longstanding rules granting expensing to small businesses, although in practical terms the rules granting full expensing to all businesses will dominate during those five years. Full expensing will impose a substantial short-term revenue loss on states that don’t decouple, though they will recoup most or all of the loss over time.

Consider Raising Revenue From Corporations and Highest-Income Families

The federal tax law’s extraordinary windfall for corporations and very high-income households will further concentrate income and wealth at the top. States may wish to reject this approach and to offset some of the windfall for those at the top by raising taxes on these households and investing the resulting revenue in middle- and lower-income Americans. Examples of policies that states could implement include:

- Recouping the ill-advised tax break for “pass-through” income. Only a small number of states are coupled to the new federal deduction for pass-through income and will need to decouple from it to avoid losing revenue. But all states could go further and impose a surcharge on pass-through income that will benefit from this unwarranted giveaway, the benefits from which are highly tilted to the wealthy and large companies.[13] Alternatively (or in addition), states could follow the example of California, Illinois, and Massachusetts and impose a low-rate tax directly on pass-through businesses.[14]

- Establishing a strong minimum corporate income tax. States could impose a corporate minimum tax based on a measure of in-state corporate activity that is less easily manipulated than corporate profits, such as a minimum tax tied to gross receipts or the “value added” by the firm — basically, the difference between the company’s purchases of inputs from independent firms and its sales of finished products. New Jersey and Kentucky had low-rate gross-receipts-based minimum taxes in the recent past, and New Hampshire still levies a “Business Enterprise Tax” based on the value added by the company.

- Closing loopholes that profitable corporations use to avoid state taxes. The minority of states with corporate income taxes that haven’t yet implemented “combined reporting” — a tax accounting method that treats parent corporations and their subsidiaries as one corporation for tax purposes — could do so. And both they and existing combined reporting states could follow the lead of Oregon, Montana, and several other states and include foreign tax haven subsidiaries under this method. This will help states avoid revenue losses they are otherwise likely to experience because the shift to a territorial corporate tax system at the federal level will increase incentives for multinational corporations to disguise U.S.-earned profits as foreign profits.

- Raising state-level taxes on the profits of corporations and/or raising rates for the wealthiest households. More than 15 states have cut their corporate income tax rates in recent years in misguided attempts to boost their economies. The tax windfall that corporations will receive under the federal tax legislation creates an opportunity for states to raise state corporate tax rates to fund investments in middle- and low-income families while still leaving corporations paying significantly lower combined state and federal corporate taxes than before. States could similarly raise income tax rates for very high-income residents to recoup some of the windfall these households will receive from the federal tax legislation. States also could consider creating a state surcharge on carried interest to recoup revenue lost at the federal level to a widely derided loophole that allows hedge fund managers and others to pay lower taxes on their income than other wage earners and salaried individuals.

Consider SALT “Workarounds” as Part of Broader Plan

Many state policymakers are justifiably concerned that the new tax law’s $10,000 cap on the federal deduction for state and local taxes (SALT) will make it harder for them to invest in schools, roads, and other building blocks of strong state economies. Some are exploring ways to restructure their tax codes to protect taxpayers from the cap. States heavily affected by the SALT caps should give such “workarounds” thoughtful consideration — but should do so as part of a more comprehensive response to the law’s effects, such as described in this paper.

Workarounds might diminish the SALT cap’s harm, though implementing them involves significant technical and legal challenges, and states should be careful in structuring them. Most of the direct beneficiaries of workarounds — taxpayers paying over $10,000 in state and local taxes — are relatively well-off, and many will get an overall federal tax cut. Giving them a still larger federal tax cut as a result of a workaround may be justifiable as part of a broader state policy response to protect state revenues — especially revenues raised in a progressive manner — but workarounds should not be a state’s only response.

Republican Tax Plans Cost More — and Add Less to Growth — Than Proponents Claim

Commentary: Congressional Budget Plan a Major Step Toward Costly, Ill-Advised Tax Cuts

End Notes

[1] These estimates are from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and reflect its reading of the “default” outcomes for states — i.e., the outcomes assuming no state policy changes beyond conformity with the federal code, and no behavioral responses from taxpayers.

[2] Phil Oliff and Nicholas Johnson, “The Impact of State Income Taxes on Low-Income Families in 2010,” CBPP, November 15, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/research/the-impact-of-state-income-taxes-on-low-income-families-in-2010.

[3] Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR), Preliminary Estimates of the Effect of the 1986 Federal Tax Reform Act on State Personal Income Tax Liabilities, December 8, 1986, Washington, D.C., http://www.library.unt.edu/gpo/acir/Reports/staff/SR-2.pdf. ACIR did not have data for four states: Arizona, Idaho, New Mexico, and South Carolina. Also, ACIR’s estimates incorporated certain taxpayer behavioral changes. A static model would have resulted in projections of even larger state revenue gains.

[4] The $80 billion net tax cut figure is an estimate based on published and unpublished Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy data. ITEP’s published estimates find that in 2019, the top 1 percent of taxpayers nationally will receive a tax cut from the personal, corporate, and estate tax provisions totaling $85 billion. See https://itep.org/finalgop-trumpbill/.

[5] The federal changes broadened the definition of corporate taxable income, and those provisions — assuming state conformity — will increase revenue in some states. For example, the new law eliminates the domestic production deduction, which reduces taxes for manufacturers. It also places (different) limits on the ability of corporations to deduct interest expenses and to use losses to offset prior-year and subsequent-year profits. Some states already are decoupled from one or more of these provisions, reducing the aggregate revenue gain. Moreover, the federal law’s “full expensing” provision described in this report will impose a substantial short-term revenue loss on states that don’t decouple, though they will recoup most or all of the loss over time. Also, the shift to a “territorial” corporate income tax system likely will reduce federal and state corporate income tax revenue over time, though the magnitude is uncertain. A provision subjecting to immediate taxation (albeit at sharply reduced rates) the large amount of cash held by the foreign subsidiaries of U.S. corporations could potentially provide substantial revenue to states, but given the revenue at stake, state attempts to piggyback on this “deemed repatriation” provision seem likely to generate legal challenges that could take considerable time to resolve.

[6] Reuven S. Avi-Yonah et al., “The Games They Will Play: Tax Games, Roadblocks, and Glitches Under the New Legislation,” December 7, 2017, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3084187 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3084187.

[7] Joel Friedman and Chad Stone, “Republican Tax Plans Cost More — and Add Less to Growth — Than Proponents Claim,” CBPP, updated December 14, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/republican-tax-plans-cost-more-and-add-less-to-growth-than-proponents-claim.

[8] Betsy Z. Russell, “Idaho Governor Pitches Tax Cuts,” The Spokesman-Review, January 8, 2018, http://www.spokesman.com/blogs/boise/2018/jan/08/idaho-governor-pitches-tax-cuts/.

[9] Elizabeth McNichol and Samantha Waxman, “States Face Revenue Shortfalls in 2017 Despite Growing Economy,” CBPP, updated October 4, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-faced-revenue-shortfalls-in-2017-despite-growing-economy.

[10] See Robert Greenstein, “Commentary: Congressional Budget Plan a Major Step Toward Costly, Ill-Advised Tax Cuts,” CBPP, October 26, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/federal-tax/commentary-congressional-budget-plan-a-major-step-toward-costly-ill-advised-tax-cuts. While the budget resolution does not determine what Congress will do in coming months, it describes the Republican majority’s priorities.

[11] Oliff and Johnson.

[12] Reid Wilson, “Trump Tax Law Poised to Create Windfall for States,” The Hill, January 9, 2018, http://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/368017-trump-tax-law-poised-to-create-windfall-for-states.

[13] Chye-Ching Huang, “Senate’s ‘Pass-Through’ Tax Cut Favors Biggest Businesses and Wealthiest Owners,” CBPP, November 14, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/senates-pass-through-tax-cut-favors-biggest-businesses-and-wealthiest-owners.

[14] See Darien Shanske, “Another Way the Empire [State] Can Strike Back,” January 4, 2018, https://medium.com/whatever-source-derived/another-way-the-empire-state-can-strike-back-465d6496e928.

More from the Authors