Most Parents Leaving TANF Work, But in Low-Paying, Unstable Jobs, Recent Studies Find

End Notes

[1] The authors would like to thank Nick McFaden for his assistance.

[2] Elisa Minoff, “The Racist Roots of Work Requirements,” Center for the Study of Social Policy, February 2020, https://cssp.org/resource/racist-roots-of-work-requirements/.

[3] Liz Schott and LaDonna Pavetti, “Changes in TANF Work Requirements Could Make Them More Effective in Promoting Employment,” CBPP, February 26, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/changes-in-tanf-work-requirements-could-make-them-more-effective-in.

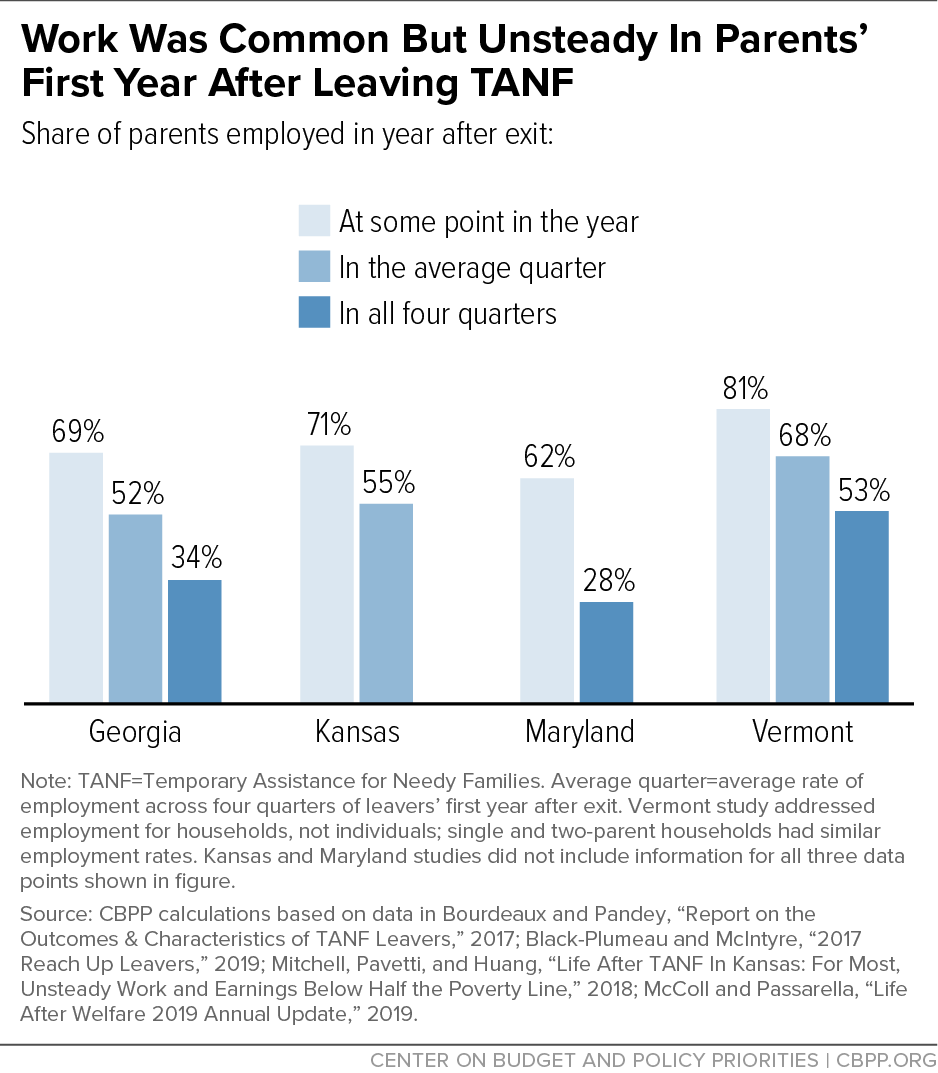

[4] Carolyn Bourdeaux and Lakshmi Pandey, “Report on the Outcomes and Characteristics of TANF Leavers,” Center for State and Local Finance, Georgia State University Andrew Young School, March 15, 2017, https://cslf.gsu.edu/download/outcomes-and-characteristics-of-tanf-leavers/?wpdmdl=6494571&refresh=5f7852f89a8bc1601721080.

[5] CBPP calculations based on data in Deleena Patton et al., “The Well-Being of Parents and Children Leaving WorkFirst in Washington State,” Research and Data Analysis Division, Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, November 2016, https://www.dshs.wa.gov/sites/default/files/rda/reports/research-11-216.pdf. Data are for parents who received TANF in state fiscal year 2011 and subsequently left and did not return during the 36-month observation period.

[6] Andrew Van Dam, “As permanent economic damage piles up, the Covid Crisis is looking more like the Great Recession,” Washington Post, August 25, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/08/25/permanent-economic-damage-piles-up-covid-crisis-is-looking-more-like-great-recession/.

[7] Chad Stone, “Jobs Report: Improvements Slowing, Jobs Hole Remains Deep,” CBPP, October, 2, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/jobs-report-improvements-slowing-jobs-hole-remains-deep; Andrew Van Dam and Heather Long, “Moms, Black Americans and educators are in trouble as economic recovery slows,” Washington Post, October 2, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/10/02/september-jobs-inequality/; Jocelyn Frye, “On the Frontlines at Work and at Home: The Disproportionate Economic Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Women of Color,” Center for American Progress (CAP), April 23, 2020, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/04/23/483846/frontlines-work-home/.

[8] Sarah Jane Glynn, “Breadwinning Mothers Continue To Be the Norm,” CAP, May 10, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/05/10/469739/breadwinning-mothers-continue-u-s-norm/.

[9] Frye, op. cit.

[10] Office of Family Assistance, Administration for Children and Families, Department of Health and Human Services, “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2019,” November 5, 2020, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/characteristics-and-financial-circumstances-of-tanf-recipients-fiscal-year-2019.

[11] Glynn, op. cit.; Van Dam and Long, op. cit.

[12] Brynne Keith-Jennings and Raheem Chaudhry, “Most Working-Age SNAP Participants Work, But Often in Unstable Jobs,” CBPP, March 15, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/most-working-age-snap-participants-work-but-often-in-unstable-jobs.

[13] Tazra Mitchell, LaDonna Pavetti, and Yixuan Huang, “Life After TANF in Kansas: For Most, Unsteady Work and Earnings Below Half the Poverty Line,” CBPP, February 20, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/life-after-tanf-in-kansas-for-most-unsteady-work-and-earnings-below.

[14] National Strategic Planning and Analysis Research Center (NSPARC), “Programmatic and Labor Market Outcomes: SNAP/TANF Participants,” Mississippi State University, 2018, https://www.mdhs.ms.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SNAP_TANF-Report.pdf.

[15] Leslie Black-Plumeau and Robert McIntyre, “Leaving Reach Up: How did the experiences of Vermont’s welfare leavers compare to earlier leavers?” Black-Plumeau Consulting, LLC, July 13, 2015, https://dcf.vermont.gov/sites/dcf/files/ESD/Report/2013%20Reach%20Up%20Leavers%20Report%20-%20July%2013%2C%202015%20%28Final%29.pdf; Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, “2017 Reach Up Leavers,” October 1, 2019, https://dcf.vermont.gov/sites/dcf/files/2017%20Reach%20Up%20Leavers%20Report. These studies gathered data on employment for households rather than individuals. They included single and two-parent households; employment rates are comparable for both groups.

[16] CBPP calculations based on data in Bourdeaux and Pandey, op. cit.

[17] CBPP calculations based on data in Rebecca McColl and Letitia Logan Passarella, “The Role of Education in Outcomes for Former TCA Recipients,” Ruth H. Young Center for Families and Children, University of Maryland School of Social Work, 2019, https://www.ssw.umaryland.edu/media/ssw/fwrtg/welfare-research/work-supports-and-initiatives/The-Role-of-Education.pdf.

[18] McColl and Passarella, “The Role of Education in Outcomes for Former TCA Recipients,” op. cit.

[19] Shelly Osborn et al., “Colorado Works Exit Survey Project Summary of Fiscal Year 2016/2017 Data Collection – Waves 1, 2, and 3,” ICF, November 1, 2017.

[20] Nationally, states report that 22 percent of cases close due to employment or excess income or resources, 21 percent due to inability to complete requirements, 13 percent due to sanctions or time limits, and 33 percent for unspecified reasons. See Office of Family Assistance, op. cit.

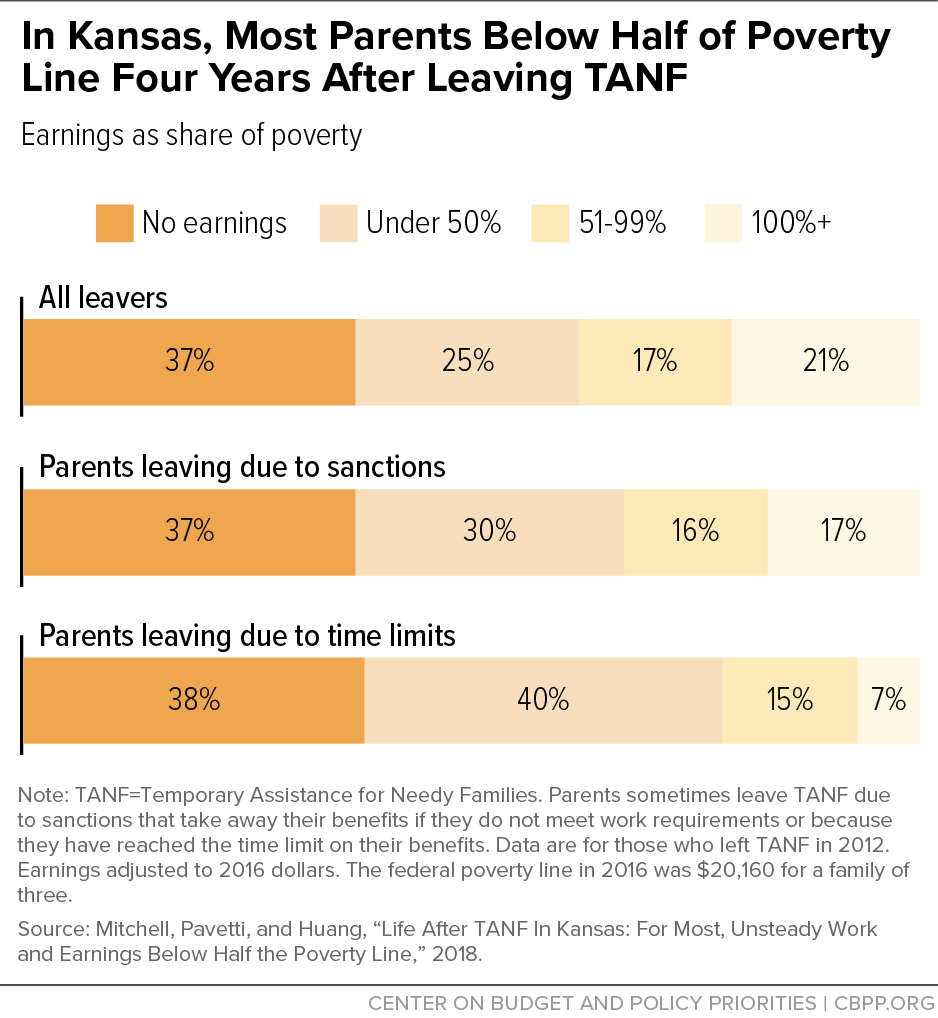

[21] Mitchell, Pavetti, and Huang, op. cit.

[22] Tazra Mitchell, “Research Note: Contrary to Maine Officials’ Claims, TANF Time Limit Leaves Most Families Without Work or Cash Assistance,” CBPP, August, 15, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/research-note-contrary-to-maine-officials-claims-tanf-time-limit.

[23] CBPP calculations based on data in Bourdeaux and Pandey, op. cit.

[24] Bourdeaux and Pandey, op. cit.

[25] Rebecca McColl and Letita Logan Passarella, “Life After Welfare: 2019 Annual Update,” Ruth H. Young Center for Families and Children, University of Maryland School of Social Work, 2019, https://www.ssw.umaryland.edu/media/ssw/fwrtg/welfare-research/life-after-welfare/life2019.pdf.

[26] McColl and Passarella, “The Role of Education in Outcomes for Former TCA Recipients,” op. cit.

[27] CBPP calculations based on data in Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2019, op. cit.

[28] Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2019, op. cit.

[29] Mitchell, Pavetti, and Huang, op. cit.

[30] Mary Beth Vogel-Ferguson, “Family Employment Program (FEP) Redesign Study of Utah 2014: Final Report,” Social Research Institute, University of Utah College of Social Work, September 2015, https://socialwork.utah.edu/_resources/documents/dws-reports/wave-3-report_final.pdf.

[31] Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2019, op. cit.

[32] McColl and Passarella, “Life After Welfare,” op. cit.

[33] Mitchell, Pavetti, and Huang, op. cit.

[34] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Great Recession, great recovery? Trends from the Current Population Survey,” Monthly Labor Review, April 2018, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/great-recession-great-recovery.htm.

[35] Bourdeaux and Pandey, op. cit.

[36] McColl and Passarella, “Life After Welfare,” op. cit.

[37] Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2015, op. cit.

[38] Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2019 op. cit.

[39] Pamela A. Morris, Lisa A. Gennetian, and Greg J. Duncan, “Effects of Welfare and Employment Policies on Young Children: New Findings on Policy Experiments Conducted in the Early 1990s,” Social Policy Report, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2005, pp. 3-17, http://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/documents/spr19-2.pdf.

[40] Bourdeaux and Pandey, op cit.

[41] CBPP calculations based on Bourdeux and Pandey, op. cit. and HHS Poverty Guidelines. Calculations used the federal poverty line for a family of three in 2015, which was $20,090.

[42] Mitchell, Pavetti, and Huang, op. cit.

[43] McColl and Passarella, “Life After Welfare,” op. cit.

[44] CBPP calculations based on data in McColl and Passarella, “The Role of Education in Outcomes for Former TCA Recipients,” op. cit. and HHS Poverty Guidelines. Calculations used the federal poverty line for a family of three in 2013, which was $19,530.

[45] Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2019, op. cit.

[46] CBPP calculations based on Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2019, op. cit. and HHS Poverty Guidelines. Calculations used the federal poverty line for a family of three in 2018, which was $20,780.

[47] Calculations based on data in McColl and Passarella, “Life After Welfare,” op. cit.

[48] McColl and Passarella, “Life After Welfare,” op. cit.

[49] Calculations based on data in Economic Services Administration, Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, “WorkFirst Wage Progression Report – 2019 Fourth Quarter,” October 1, 2020, https://apps.leg.wa.gov/ReportsToTheLegislature/Home/GetPDF?fileName=WF%20Wage%20Progression%20Report_2019Q4%20Final_07445ffb-8f17-496c-8f34-83cac15bac57.pdf.

[50] Economic Services Administration (WA), 2020, op. cit.

[51] Fred Brooks, Anna Elizabeth Chaney, and Sara Elizabeth Mack, “Georgia’s TANF Leavers 2009-15: How Are They Faring?” Center for State and Local Finance, Georgia State University Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, February 13, 2018, https://cslf.gsu.edu/download/georgias-tanf-leavers-2009-15-how-are-they-faring/?wpdmdl=6494562&ind=1526058317130.

[52] Vogel-Ferguson, op. cit.

[53] Calculations based on data in Patton et al., op. cit. Data are for parents who received TANF in state fiscal year 2011 and subsequently left and did not return during the 36-month observation period.

[54] Bourdeaux and Pandey, op. cit.

[55] Brooks, Chaney, and Mack, op. cit.

[56] McColl and Passarella, “Life After Welfare,” op. cit.

[57] Black-Plumeau and McIntyre, 2015, op. cit..

[58] Calculations based on data in Patton et al., op. cit. Data are for parents who received TANF in state fiscal year 2011 and subsequently left and did not return during the 36-month observation period.

[59] McColl and Passarella, “Life After Welfare,” op. cit.

[60] NSPARC, op. cit.

[61] Economic Services Administration (WA), 2020, op. cit.; Economic Services Administration (WA), “WorkFirst Wage Progression and Return Report Through First Quarter 2012,” October 2012,https://apps.leg.wa.gov/ReportsToTheLegislature/Home/GetPDF?fileName=Wage%20Progression%20Report%202012Q1_1c0960f9-9be1-4e2c-b2ac-802bcf08d705.pdf.

[62] Brooks, Chaney, and Mack, op. cit.

[63] Osborn et al., op. cit.

[64] Vogel-Ferguson, op. cit.

[65] Marjorie L. Baldwin, Steven C. Marcus, and Jeffrey DeSimone, “Job Loss Discrimination and Former Substance Use Disorders,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 110, July 1, 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2885482/pdf/nihms192940.pdf; Alison Luciano and Ellen Meara, “The employment status of people with mental illness: National survey data from 2009 and 2010,” Psychiatric Services, Vol. 65, October, 1, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4182106/pdf/nihms614853.pdf; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, “10.8 Million Full-Time Workers Have a Substance Use Disorder,” The NSDUH Report, August 7, 2014, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-SP132-FullTime-2014/NSDUH-SP132-FullTime-2014.pdf.

[66] Abigail Langston, “100 Million and Counting: A Portrait of Economic Insecurity in the United States,” Policy Link and the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity at the University of Southern California, 2018, https://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/100_million_and_counting_FINAL.PDF.

[67] Calculations based on data in Patton et al., op. cit. Data are for parents who received TANF in state fiscal year 2011 and subsequently left and did not return during the 36-month observation period.

[68] Kaitlyn Petruccelli, Joshua Davis, and Tara Berman, “Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Child Abuse & Neglect, Vol. 97, August 24, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127.

[69] Vogel-Ferguson, op. cit.

[70] Schott and Pavetti, op. cit.

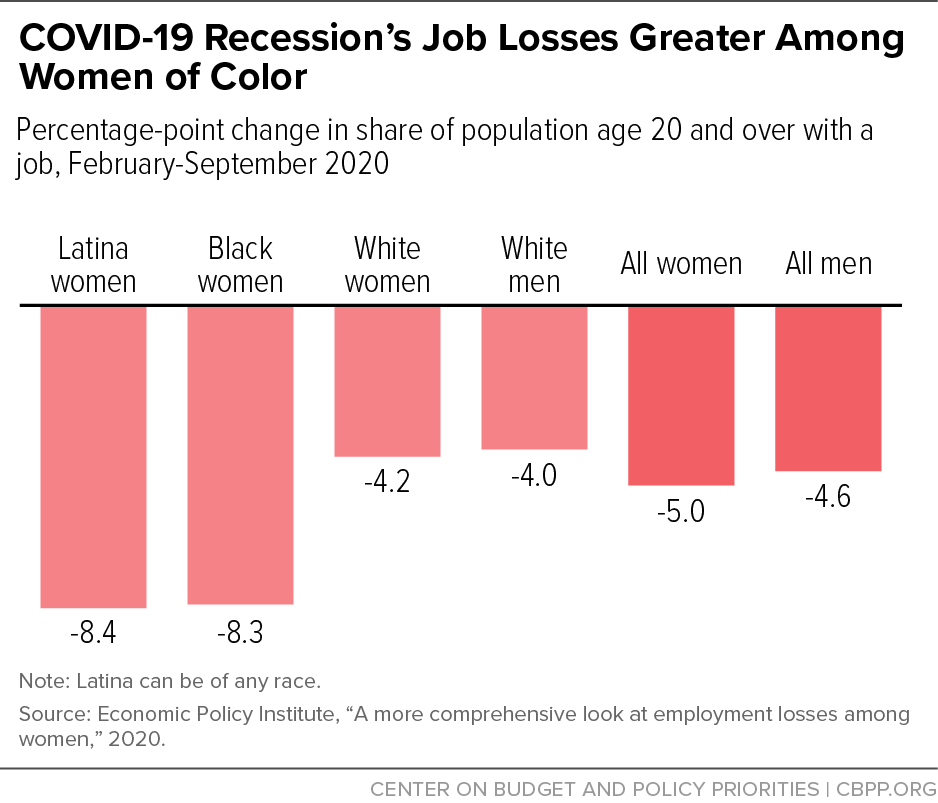

[71] Economic Policy Institute, “Chart: A more comprehensive look at employment losses among women,” October 20, 2020, https://www.epi.org/chart/gender-disparities-figure-a-a-more-comprehensive-look-at-employment-losses-among-women-change-in-employment-population-ratio-by-gender-race-ethnicity-feb-to-sept-2020/?utm_source=Economic+Policy+Institute&utm_campaign=a9e285a531-.

[72] Van Dam and Long, op. cit.

[73] For more information on the work participation rate see Elizabeth Lower-Basch and Ashley Burnside, “TANF 101: Work Participation Rate,” Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), revised October 16, 2020, www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2019/08/Oct%202020_TANF%20101%20Work%20Participation%20Rate.pdf.

[74] Schott and Pavetti, op. cit.

[75] CBPP, “Policy Basics: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families,” updated February 6, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/temporary-assistance-for-needy-families.

[76] Mitchell, op. cit.

[77] “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Employment and Training (E&T) Best Practices Study: Final Report,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, November 2016, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/SNAPEandTBestPractices.pdf; “What Works in Job Training: A Synthesis of the Evidence,” U.S. Department of Labor, Department of Commerce, Department of Education, and Department of Health and Human Services, July 22, 2014, https://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/jdt/jdt.pdf.

[78] Indivar Dutta-Gupta et al., “Lessons Learned from 40 Years of Subsidized Employment Programs,” Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2016, https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GCPI-Subsidized-Employment-Paper-20160413.pdf.

[79] Danielle Cummings and Dan Bloom, “Can Subsidized Employment Programs Help Disadvantaged Job Seekers? A Synthesis of Findings from Evaluations of 13 Programs,” MDRC, February 2020, https://www.mdrc.org/publication/can-subsidized-employment-programs-help-disadvantaged-job-seekers.

[80] LaDonna Pavetti, Liz Schott, and Elizabeth Lower-Basch, “Creating Subsidized Employment Opportunities for Low-Income Parents: The Legacy of the TANF Emergency Fund,” CBPP and CLASP, February 16, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2-16-11tanf.pdf.

[81] Alicia Meckstroth et al., “Teaching Self-Sufficiency Through Home Visitation and Life Skills Education,” Mathematica Policy Research, July 30, 2009, https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-findings/publications/teaching-selfsufficiency-through-home-visitation-and-life-skills-education.

[82] Heather Hahn, Teresa Derrick-Mills, and Shayne Spaulding, “Measuring Employment Outcomes in TANF,” Urban Institute, August 28, 2020, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/measuring-employment-outcomes-tanf.