Beginning in November 2011, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback and a Republican-controlled legislature enacted a series of punitive eligibility changes in the state's Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance program that made it harder for parents who lose their job or cannot work to receive the support needed to pay rent and utilities and afford basic goods. Supporters claimed that removing these supports would push families to work — implying that TANF recipients do not work, though most do — and the Brownback administration has since claimed that affected families' experiences demonstrate that "employment is the most effective path out of poverty."[1] However, the facts available do not support these claims.

Our analysis of state-collected data on the employment and earnings of Kansas parents leaving TANF cash assistance between October 2011 and March 2015 indicates that the vast majority of these families worked before and after exiting TANF, but most found it difficult to find steady work and secure family-sustaining earnings. For those exiting due to work-related sanctions and time limits, TANF policies left these families with children without access to cash assistance that they could draw upon when they hit hard times. Our main findings include:

- Most parents leaving TANF had jobs at some point, before and after leaving the program. The vast majority — 84 percent — of parents that left TANF worked at some point over the period examined (namely, the calendar quarter in which they exited TANF as well as the four quarters before and the four quarters after their exit). Moreover, work was just as common in the year before exit as in the year after exit: 7 in 10 parents worked at some point in each period.

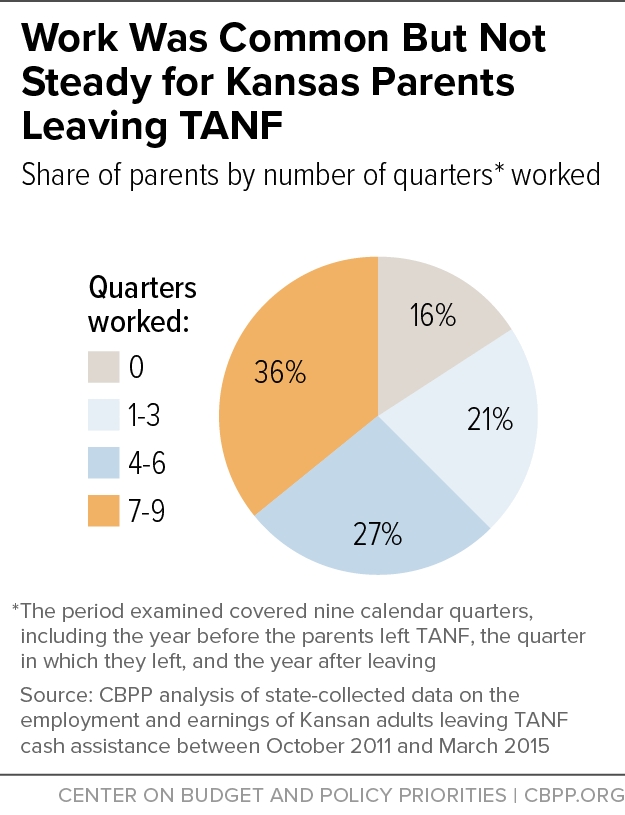

- Work was common but for most it was unsteady. About a third of the TANF parents were steady workers, working in at least seven of the nine quarters. Just over a fourth worked in four to six quarters and about one-fifth worked in just one to three quarters (see Figure 1). Because work was unstable, in any given quarter of the post-exit year, only 55 percent of parents that left TANF were working. This suggests that the barriers to work that many families face, such as lower education and volatile work schedules, continue to affect their employment prospects after they leave TANF.

- Although some parents' earnings rose after leaving TANF, the majority remained far below the federal poverty line. Some parents had earnings increases after exit, but in the year after leaving TANF, nearly two-thirds of parents had either no earnings or earnings below 50 percent of the poverty line (or below $10,080 for a family of three in 2016, hereafter "deep-poverty earnings").[2] Nearly the same share had deep-poverty earnings four years after exit, data for the parents who exited TANF in the early part of the study show. Among the parents with four years of post-exit data, their median annual earnings in the fourth year after exit were just 71 percent of the income a family would have received from TANF if they had no earnings and received the full benefit for a family of three every month that year.

- Evidence does not support proponents' claims that families terminated from TANF due to policies such as harsh work sanctions and shorter time limits were thriving. For the parents exiting due to work sanctions and time limits for whom we have four years of exit data, median earnings in the fourth year after exit were especially low: $2,175 (11 percent of the poverty level) and $1,370 (7 percent of the poverty level), respectively. For the parents exiting due to work sanctions, after four years more than one-third of them had no earnings, nearly 7 in 10 had no earnings or earnings below the deep-poverty level, and more than 8 in 10 had no earnings or earnings below the poverty level.

These outcomes demonstrate that most families exiting TANF did not make considerable progress towards economic security. They are consistent with other TANF studies suggesting that work requirements and other rigid eligibility policies in TANF do little over the long term to help families find work and escape poverty.[3] These findings sharply contradict claims by Kansas and the Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA), an organization that promotes state work requirements in economic security programs such as federal food assistance and Medicaid.[4] As our companion report, "Study Praising Kansas" Harsh TANF Work Penalties Is Fundamentally Flawed," details, even FGA's deeply flawed analysis does not support the claim that families that exited TANF because of a work sanction are thriving.[5]

The substantial evidence that harsh eligibility policies harm families living on the edge should serve as a cautionary tale not only to policymakers in other states, but also to President Trump and Republican congressional leaders, who may seek this year to severely cut other programs — such as SNAP (formerly food stamps), housing assistance, and Medicaid — and encourage (or even mandate) states to pursue similar harsh policies in those programs.

Further, considerable research suggests that extremely low family income, which does not allow families to meet their basic needs, is likely to have long-term negative consequences for the health and development of the children in these Kansas families.[6]

States have virtually unfettered flexibility to set eligibility policies and processes in TANF.[7] Over the last six years, Governor Brownback and like-minded Kansas lawmakers have used this flexibility to make it more difficult for families to obtain, maintain, and regain TANF benefits by implementing a range of stringent work-related sanctions and time-limit policies.[8] These policies include:

- Application changes, including upfront job requirements that make it harder for families to receive assistance. In November 2011, the state began requiring TANF applicants to complete 20 job contacts per week as a condition of eligibility, which means they had to complete these job contacts before their application could be approved.[9] In July 2013, policymakers replaced the pre-eligibility job search requirement with a requirement that recipients register in the state’s public workforce system and complete a work skills assessment before assistance would be approved.[10]

- Harsher penalties for not meeting the program's work requirements. In November 2011, Kansas enacted new rules disqualifying an entire family from TANF for three months the first time the family fails to meet the work requirement and for progressively longer periods for repeat instances of noncompliance.[11] (Under the prior policy, sanctioned families could return to TANF as soon as they came into compliance.) Also, in July 2013, the state made it much easier to sanction families for missing a work program appointment, meaning that a family in crisis may lose the help that they need if at the last minute they are not able to inform their caseworker of what's preventing them from attending the scheduled meeting.

- Shorter time limits. When Kansas first implemented TANF, it imposed a 60-month limit on receipt of assistance, like the majority of states. But Kansas cut the time limit to 48 months in 2011, to 36 months in 2015, and to 24 months in 2016.[12]

- Shorter work exemption for parents of infants. In May 2013, the state narrowed the exemption from work activities for parents with very young children so that only parents whose youngest child is two months old or less can qualify, rather than six months as under the previous policy. This means that parents now have far less time to stay home to bond with their infants during a critical period of cognitive and social development and face the difficult task of finding child care for infants.

These policy changes are not new and not unique to Kansas. In recent years, a number of states implemented harsher work requirements and shorter time limits, despite evidence that these rigid policies exacerbate, rather than reduce, poverty for some of the most vulnerable families.[13] As a result, TANF is largely disappearing in a growing number of states; in 15 states (including Kansas), ten or fewer families receive TANF cash benefits for every 100 families in poverty.[14]

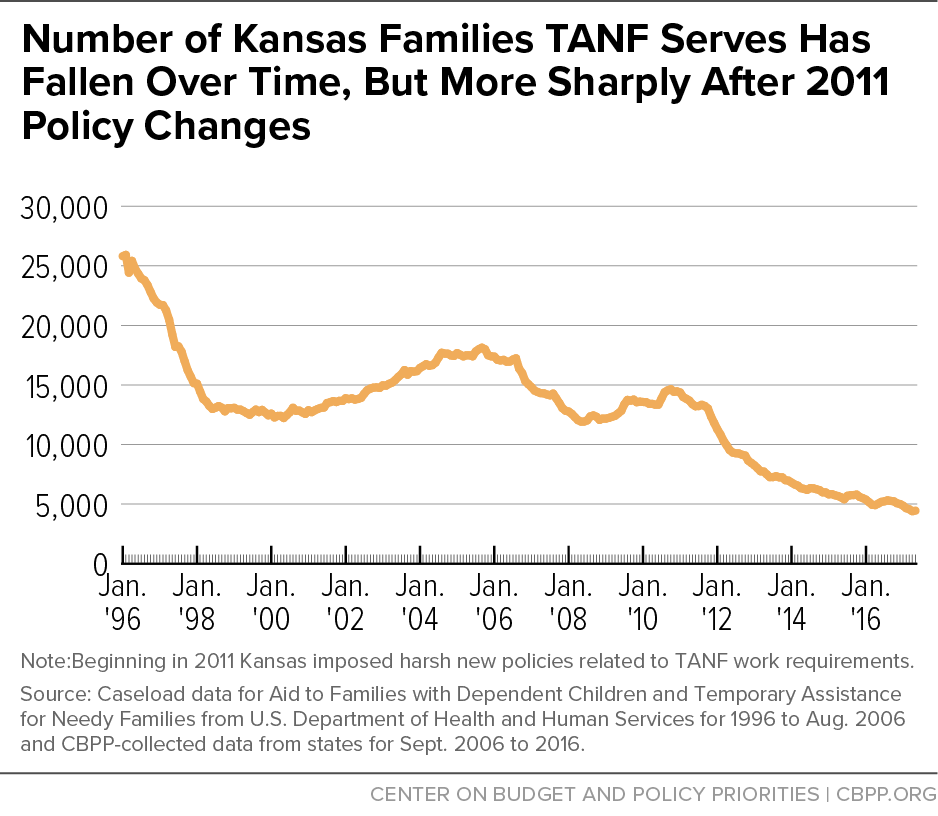

Kansas' TANF cash assistance caseload, hereafter referred to as families served, has fallen substantially since the state implemented its new work and time limit policies (see Figure 2). The number of families served has plummeted by more than half, from 13,014 in October 2011 to 5,231 in October 2016. Previously, that number ebbed and flowed as the economy and low-income programs changed. The steepest drop in families served occurred in the mid-to-late 1990s due to a strong economy, the 1996 welfare law, and other factors such as expansions in the Earned Income Tax Credit. Thereafter, the number rose in the early 2000s, fell in the mid-2000s, and increased again when the Great Recession caused poverty and joblessness to spike. With the recent changes, few families living in poverty now have access to benefits that help them meet their basic needs when work is not feasible or available. For every 100 Kansas families in poverty in 2015-16, only ten received cash assistance from TANF — down from 17 families in 2011-12 and 52 families in 1995-96.[15]

The decline in the number of families receiving TANF cash assistance reflects both a drop in the number of applications submitted and approved and a rise in the number of people exiting the program. The state estimates that changes in its application requirements and processes — including its upfront work activity requirements — have led to fewer approved TANF applications and are a major cause of the decline.[16] The state estimates that other policy changes, including the harsher sanctions and shortened time limit, are another significant factor. The state also estimates that nearly twice as many families will be forced off TANF due to the time limit in fiscal year 2019 as in 2015.[17]

In this analysis, we used a data set created by the state that matches data for families exiting TANF with earnings data from the state's quarterly unemployment insurance wage records. We examined the quarterly employment and earnings patterns for all Kansas households with a parent exiting TANF between October 2011 and March 2015.[18] Any earnings in a quarter — no matter how small — indicate that a person was employed in a job that was required to provide quarterly wage data to the state. Because our analysis is limited to data available from quarterly unemployment insurance records, we do not know how many hours parents worked or their hourly wage. We also do not capture earnings for TANF recipients who may have worked in a neighboring state. Nor do we know whether parents later returned to TANF, unless they returned and then left again within the period examined.

For all families, we compared the data for the four quarters prior to the family's exit to the four quarters after their exit from TANF. (The full "study period" thus includes nine quarters: the exit quarter along with the four quarters before it and the four quarters after it.)[19] Four years of post-exit data are available for the earliest cohort of leavers, or the "2012 cohort," and we use these data to examine households' employment and earnings four years after exiting TANF. We analyzed data for all families exiting TANF as well as for subgroups of families according to the reason they exited TANF. Further, we compared earnings to the federal poverty line; while other sources of income — such as child support or food assistance — may have lifted above the poverty or deep-poverty thresholds some families whose earnings alone left them below those thresholds, the state data do not include those sources of support. See Appendix I for more details on the methodology of this study.

This study is a "descriptive" study that allows us to describe employment and earnings trends over time and assess how outcomes differ among various groups of TANF families. These data do not enable us to explain why the documented outcomes occur. The gold standard for testing the effectiveness of an intervention is a randomized control trial, which randomly assigns families to a treatment group that is subject to a new set of policies (such as a shorter time limit or work requirement) and compares their outcomes with those from a control group subject to the previous policies. Only then can the differences between the two groups be attributed to the intervention.

Descriptive studies like this one do not provide evidence of whether recent policy changes in Kansas boosted employment and earnings — policymakers' purported goal — but they can increase our understanding of the economic and work experiences of TANF families, highlight groups of families whose outcomes may be troubling such as those with very low earnings, and suggest areas for rigorous experimentation aimed at improving such experiences.

Case Characteristics and Reasons for Exits

Some 22,505 household heads (hereafter "parents") exited TANF between October 2011 and March 2015. The average household included approximately three people (see Table 1). Most of the households — about 83 percent — were single-parent households; 17 percent were two-parent households. Our unit of analysis in this study is adults in the family, meaning that parents' earnings are combined for multiple-parent households.[20]

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Household Size |

Count |

Percent |

| 1 member |

1,073 |

4.8% |

| 2 members |

8,607 |

38.2% |

| 3 or more members |

12,825 |

57.0% |

| Average |

2.94 |

/ |

| Total number of exiting households |

22,505 |

100% |

| Number of Households by Number of Adults |

Count |

Percent |

| 1 adult |

18,587 |

82.6% |

| 2 adults |

3,905 |

17.4% |

| 3 adults |

13 |

<1.0% |

| Average |

1.17 |

/ |

Parents in this study left TANF for various reasons. Nearly 3 in 10 exited due to failure to meet work requirements, just over 2 in 10 exited due to income above the eligibility limit, and about 1 in 10 exited due to time limits. The rest exited for reasons including failing to cooperate with child support enforcement requirements, moving out of state or ending contact with caseworkers, and vague or unspecified household decisions such as requesting to close their case.[21]

The 1996 welfare law replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children entitlement program with the TANF block grant, which provides funds to states for short-term income assistance, work programs, and other crucial supports for families with children living in poverty. Families often turn to TANF when a change in their circumstances — such as losing a job, giving birth, getting divorced, fleeing domestic violence, or experiencing a medical issue — places them in a particularly vulnerable situation. The average family using TANF cash assistance in Kansas consists of one parent and two children, with two-thirds of families having children ages 5 and under.

To be eligible for assistance initially, families must earn no more than $519 per month (for a family of three). For families already receiving cash assistance, access to regular benefits ends when their income exceeds $1,162 per month (for a family of three). To smooth the transition off TANF, families reaching this income level become eligible for a special $50 "post-TANF" payment for five months.a (These families account for about 20 percent of all exits in this leavers study.) A family of three with no income receives a maximum monthly cash grant of $429.b

aFamilies that leave the program but later return can receive this payment for an additional five months.

bKansas benefit levels vary within the state, either by county or by region; the thresholds used here are the ones that apply to the majority of the state. Data come from Tables I.E.4., II.A.4, and IV.A.6 in the 2015 Welfare Rules Databook, Urban Institute, http://wrd.urban.org/wrd/data/databook_tabs/2015/I.E.4.xlsx, http://wrd.urban.org/wrd/data/databook_tabs/2015/II.A.4.xlsx, and http://wrd.urban.org/wrd/data/databook_tabs/2015/IV.A.6.xlsx.

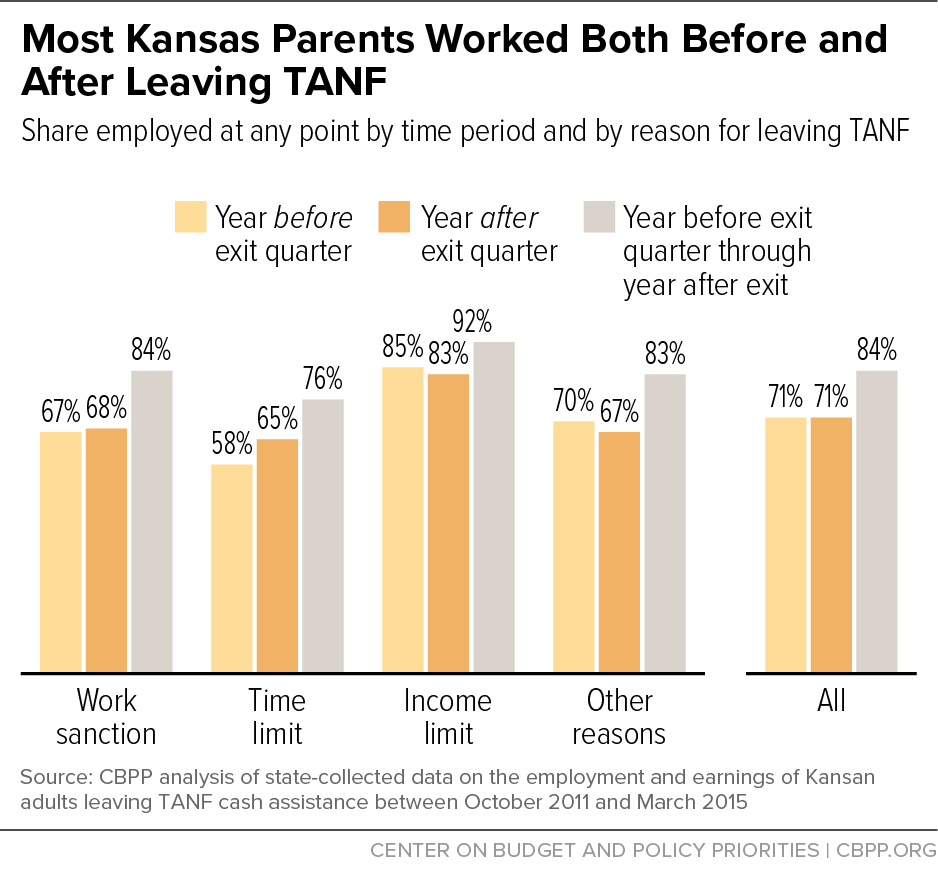

Kansas' imposition of shorter time limits and work requirements (with harsh penalties for not meeting them) reflected the assumption that public benefit recipients do not work, but the data do not support this assumption. Eighty-four percent of the 22,505 exiting TANF parents worked at some point from the year before exiting through the year after exiting. Attesting to their strong attachment to the labor force, the work rate for exiting parents was just as high before they left the program as after: approximately 71 percent worked in the year prior to exit and 71 percent worked in the year after exit (see Figure 3). The high work rates both before and after exit suggest that parents' stays on TANF may have been quite short, with families using the program as it was intended — as a temporary safety net when work is not available or feasible.

High work rates among public benefit recipients are not unique to Kansas — or to TANF, as studies of other programs show:

- Food assistance. A study of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) showed that among SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult, more than half work while receiving SNAP and more than 80 percent work in the year before or the year after receiving SNAP. The figures are even higher for families with children: more than 60 percent work while receiving SNAP, and almost 90 percent work in the prior or subsequent year.[22]

- Rental assistance. Nearly 70 percent of non-disabled, working-age households participating in the Housing Choice Voucher program have at least one member who is working or worked recently.[23]

- Medicaid. Nearly 8 in 10 non-disabled adults with Medicaid coverage live in working families, and nearly 60 percent are working themselves. Of those not working, more than one-third reported that illness or a disability was the primary reason, 28 percent reported that they were taking care of home or family, and 18 percent were in school.[24]

While the vast majority of parents worked, their employment was unsteady. Many struggled with periods of joblessness that left them with earnings that were far too low to support the needs of a family, as explained below. Only about a third of the TANF parents had steady employment, working in at least seven of the nine quarters. Just over a quarter worked in four to six quarters and about one-fifth worked in one to three quarters.

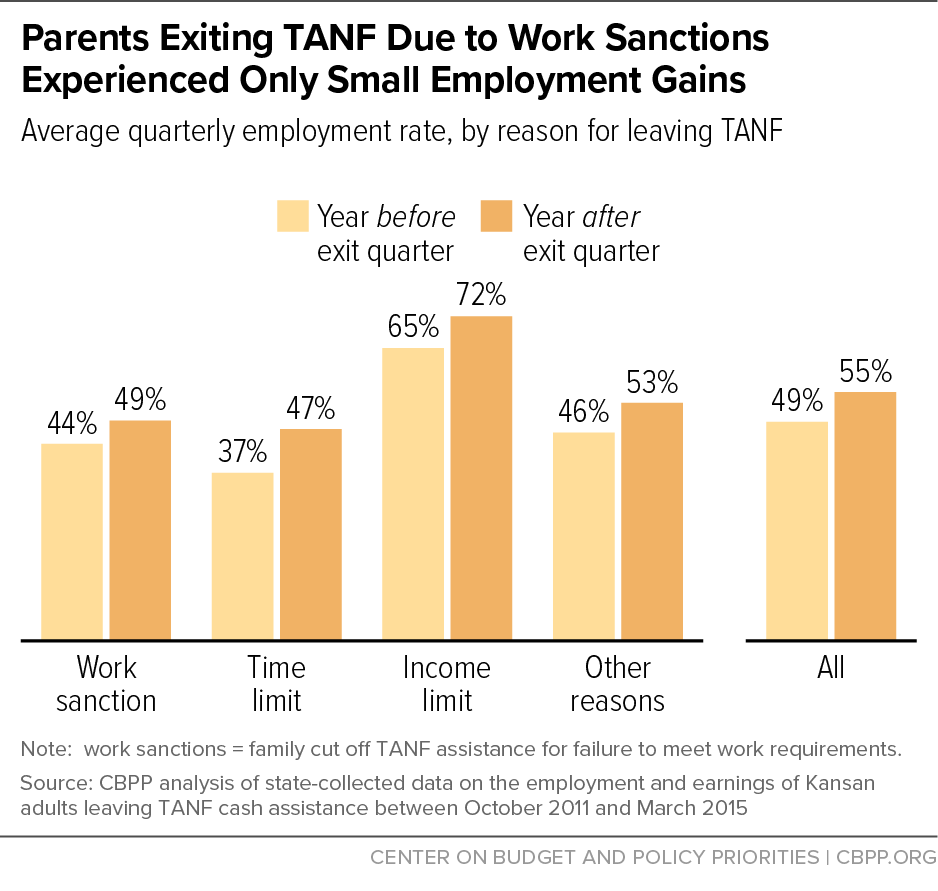

Because work was unsteady, the share of TANF leavers working in any single quarter was substantially lower than the share that worked at any point in the year before or after exit. In any given quarter over this period, about half of the parents had no earnings. On average, TANF families saw modest gains in their quarterly work rate from the year prior to exit to the year after exit: before leaving TANF, 49 percent were employed in an average quarter; after leaving, 55 percent were (see Figure 4).

The majority of parents who left TANF because of a work sanction worked both before and after exiting TANF; over that period, including the exit quarter, 84 percent worked — and they were just as likely to work before exiting TANF as after. Their work was very unsteady, however, with only about a quarter working between seven and nine quarters over the study period. As a result, in any given quarter the share working never reached 50 percent and increased only slightly after they exited TANF, from 44 to 49 percent. Parents who exit TANF due to a work sanction may not be able to return for assistance if they later lose their job, even if they have no other means of support.

Parents that left TANF because they reached the time limit saw the biggest increase in their work rates, but in the average quarter the year after exiting, their work rate remained extremely low, at 47 percent. Three-quarters worked at some point (including the exit quarter) during the study period, but only about a quarter worked steadily, between seven and nine quarters. The share working at any point in the year after exiting TANF rose only modestly over the year prior to exiting — from 58 to 65 percent.

And, because of the time limit, these families cannot return to TANF if they are laid off from a job, their hours are substantially reduced, or they are confronted with a personal or family emergency. Research shows that families exiting due to time limits are likelier than the average TANF family to have significant barriers to employment, including limited education and physical and mental health challenges.[25]

Although most parents worked in the year before and/or after leaving TANF, most had earnings below half the poverty line, (or $10,080 for a family of three in 2016) in the year after exit. Working adults enrolled in economic security programs are concentrated in low-wage and low-quality jobs[26] and are often saddled with volatile work schedules, no benefits such as paid sick leave, and fluctuating work hours over which they have no control. This not only causes workers' incomes to fluctuate but also creates barriers to retaining employment and advancing in their careers by making it harder to arrange child care, search for a new job, or attend school or training. As such, it is not uncommon for adults receiving cash assistance to regularly move in and out of low-wage work and have very low earnings as a result.

In the year after exiting TANF, nearly two-thirds of parents in the study had either no earnings or annual earnings below half the poverty line. This includes the 6,636 parents who never worked in the post-exit year as well as the roughly 8,000 parents who worked at some point in that year but had earnings below this level. Only 14 percent of the parents — or 3,160 parents — had earnings at or above the federal poverty level (see Table 2).

| TABLE 2 |

|---|

| Annual earnings by earnings group, adjusted for inflation, 2016 dollars and 2016 federal poverty level |

|---|

| Earnings Group |

Number of Parents |

Share of All Parents |

|---|

| $0 Earnings |

6,636 |

29.5% |

| Below 25% federal poverty level (FPL) |

4,985 |

22.2% |

| 25 - 49% FPL |

3,063 |

13.6% |

| 50 - 74% FPL |

2,658 |

11.8% |

| 75 - 99% FPL |

2,003 |

8.9% |

| 100% FPL and Above |

3,160 |

14.1% |

| Total |

22,505 |

100% |

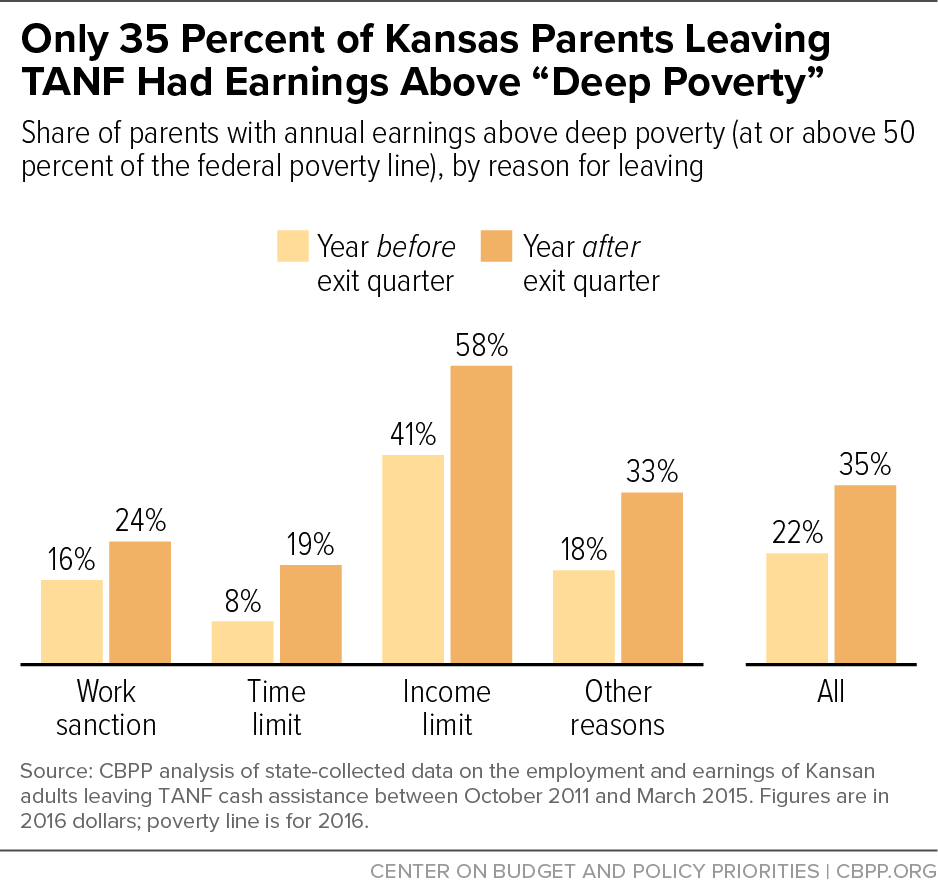

Although the majority of parents had earnings below half the poverty line after they left TANF, some did see their circumstances improve. About a third of parents had sufficient annual earnings to move them above the deep poverty line in the year after exiting TANF, compared to about a fifth of parents in the year before exiting (see Figure 5). Given that families often turn to TANF at times of crisis or other serious need, it is not surprising that after leaving TANF some are able to work more consistently. Further, Kansas' economy, like the nation's, was improving during the time this study covers, so we would expect some earnings gains simply due to the strengthening economy, although we do not know the magnitude or the impact of these overall trends.

Despite the earnings gains, median earnings for the 7 in 10 parents with earnings in the year after exit remained far too low to cover a family's basic needs: $9,602, or about 48 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) for a family of three (see Appendix II). This descriptive study does not look at other supports or resources that may have lifted families' total incomes closer to the poverty threshold, such as tax credits for working families and child support. The vast majority of parents with earnings increases likely saw increases in their income from the Earned Income Tax Credit, a refundable tax credit for families that work but earn low wages so they can better support their children.

Parents leaving TANF due to a work sanction or time limit had the highest rate of deep-poverty earnings in the year after leaving TANF. Only 24 percent of parents leaving due to a work sanction had annual earnings above the deep poverty line in the post-exit year, up from 16 percent in the year prior to exit. Parents exiting due to the time limit saw the largest improvement but remained the least likely group to have annual earnings above the deep poverty line in both years: only 19 percent in the post-exit year, up from 8 percent in the pre-exit year, further evidence that the group affected by time limits has significant barriers to employment.

For the 2012 cohort, we can observe how TANF parents fared over a four-year period. While some parents' earnings increased above the poverty line over the four years, more than 6 in 10 had either no earnings or deep-poverty earnings in the fourth year after exiting TANF (see Table 3). Especially troubling, the share of parents with no earnings rose, from 31 percent in the first year after exit to 37 percent in the fourth year.

The share of parents with earnings above the poverty line rose from 13 percent in the first year after exit to 21 percent in the fourth year, but this group still accounted for just one-fifth of those that left TANF four years earlier. The vast majority (about 80 percent) of the parents with earnings above the poverty line after four years left TANF due to increased earnings or for other, often unspecified, reasons. Parents that left due to work sanctions or time limits accounted for less than a fifth of the parents with earnings above the poverty line even though they accounted for more than 40 percent of all exits.

| TABLE 3 |

|---|

| Annual earnings by earnings group, adjusted for inflation, 2016 dollars and 2016 federal poverty level |

|---|

| Earnings Group |

Share of All Parents (One Year After Exit) |

Share of All Parents (Four Years After Exit) |

|---|

| $0 Earnings |

31.0% |

37.2% |

| Below 25% federal poverty level (FPL) |

22.6% |

15.9% |

| 25 - 49% FPL |

14.1% |

9.4% |

| 50 - 74% FPL |

11.7% |

8.6% |

| 75 - 99% FPL |

7.6% |

8.1% |

| 100% FPL and Above |

12.9% |

20.9% |

| Total |

100% |

100% |

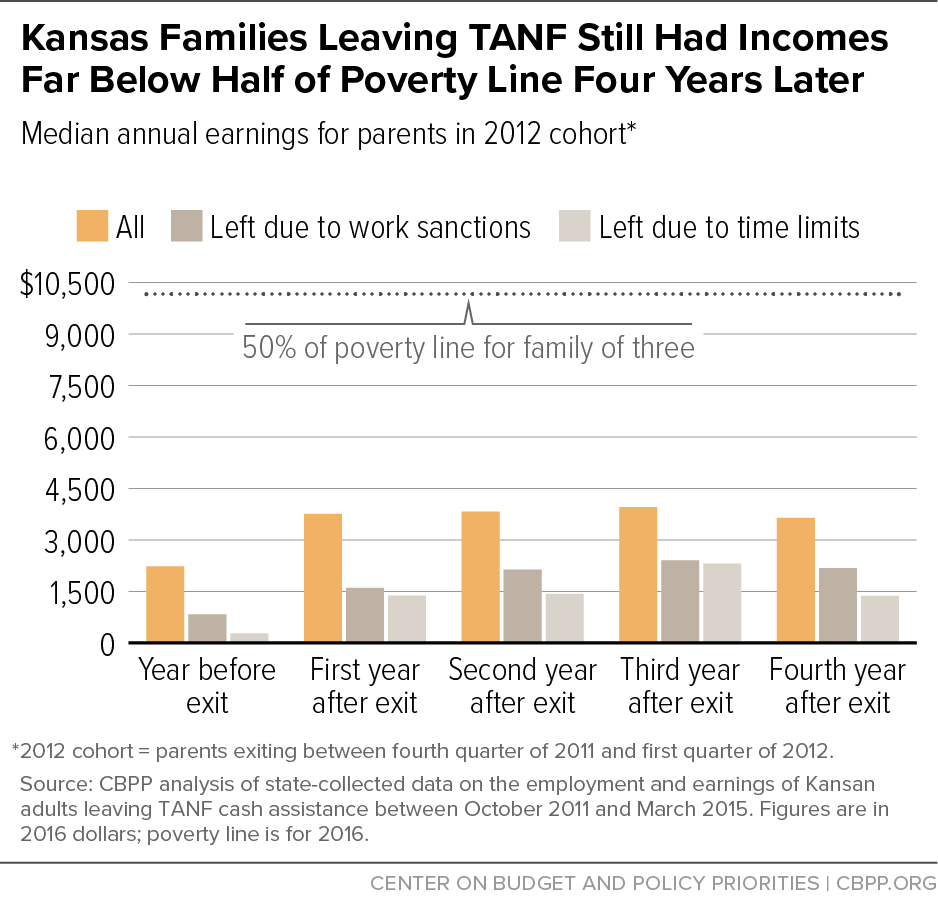

Median annual earnings for the 2012 cohort remained almost unchanged and extremely low over the four-year period (see Figure 6), at about $3,600 in the fourth year after exit or nearly 20 percent of the FPL for a family of three. In another sign that families generally were not better off from earnings alone[27] after exiting TANF, the median annual earnings for this cohort of parents in the fourth year after exit were just 71 percent of the income a family would have received from TANF if they had no earnings and received the full benefit for a family of three every month that year.

For the parents in the 2012 cohort exiting due to work sanctions, the picture is even more troubling. In the year after exit, their median earnings were just $1,601 ($133 per month), or only 8 percent of the FPL for a one-parent, two-child household and only about a third of the TANF grant for a single-parent family with two children. That isn't even enough to cover the typical monthly expenditures on natural gas and electricity for an average family in the Midwest, let alone other basics such as rent and water.[28] Their median annual earnings rose in years two and three and then fell slightly to $2,175 in the fourth year, or about 11 percent of the FPL. After four years, more than one-third of parents exiting due to work sanctions had no earnings, nearly 7 in 10 had no earnings or earnings below the deep-poverty level, and more than 8 in 10 had no earnings or earnings below the poverty level (see Table 4).

Families in the 2012 cohort that exited because they reached the time limit fared worst of all. Four years after exiting, more than 60 percent had either no earnings or earnings below 25 percent of the poverty line ($5,040 for a family of three in 2016). Their median earnings in the fourth year were just $1,370 — less than 7 percent of the FPL and slightly below their $1,378 median earnings in the first year after exit.

| TABLE 4 |

|---|

| Annual earnings by exit group and earnings group, adjusted for inflation, 2016 dollars and 2016 federal poverty level |

|---|

| Earnings Group |

Share of All Parents Exiting Due to Work Sanctions |

Share of All Parents Exiting Due to Time Limits |

|---|

| $0 Earnings |

37.0% |

38.3% |

| Below 25% FPL |

19.6% |

25.3% |

| 25 - 49% FPL |

11.2% |

14.4% |

| 50 - 74% FPL |

9.3% |

7.1% |

| 75 - 99% FPL |

6.3% |

7.6% |

| 100% FPL and Above |

16.7% |

7.3% |

| Total |

100% |

100% |

The findings of this study indicate that the vast majority of Kansas families leaving TANF did not find steady work opportunities that positioned them to make ends meet and avoid raising their children in poverty. Indeed, the median annual earnings for parents in the 2012 cohort in the fourth year after exit were just 71 percent of the income a family would have received from TANF if they had no earnings and received the full benefit for a family of three every month that year. That's a far cry from proponents' claims that the state's harsh eligibility policies lead to "Higher incomes, better lives, and more opportunity."[29]

Policymakers in other states and federal policymakers considering sharp cuts and harsh policy changes in economic security programs should heed these findings, which show that work sanctions and time limits do not address the scourge of poverty or the fact that many jobs pay inadequate wages. Rather, these findings reiterate that state and national policymakers should focus on building an economy that works for all, making work pay, and creating effective work programs that help parents prepare for work and build skills that put them on a path to economic security. The outcomes also point to the need for rigorous evaluations to determine the effectiveness of public policies, particularly those that terminate income supports entirely.

In addition to the discussion in the body of this report, the following details on the methodology of this study are worth noting:

- Four years of post-exit data are available for the earliest cohort of leavers, allowing us to assess their employment and earnings outcomes over a longer period. This subset of the sample, the "2012 cohort," exited TANF between the fourth quarter of 2011 and the first quarter of 2012.

- The Kansas Department for Children and Families paired the TANF caseload data with quarterly earnings data from the Kansas Department for Economic and Employment Services. Because the state aggregated the earnings data on a quarterly basis, it is not possible to know the amount of time each adult spent working or to infer hourly or monthly wages. Also, this data set does not capture out-of-state earnings or non-covered employment earnings, either prior to after exit from TANF. The data set also doesn't indicate how long households were enrolled in TANF or whether they worked before enrolling in the program.

- Subgroups are defined by the reason for their exit and by the year(s) in which they exited (e.g., the 2012 cohort). We disaggregated the data by the "closure code" that the state assigns to each household to identify the reason for the exit. We focus our analysis on three primary closure codes, which are related to families reaching the TANF time limit, failing to comply with the work rules, or earning income above the eligibility limit; we combine all other codes into one group labeled "other reasons." The "other reasons" category includes cases of the adult failing to cooperate with Child Support Enforcement requirements, households moving out of state or loss of contact, and vague or unspecified household decisions.

- Due to eligibility rules, sanctions, and families' changing circumstances, it is not uncommon for a small share of families to become ineligible for TANF benefits but regain eligibility soon thereafter. We treat households with multiple eligibility spells as separate cases upon their return to TANF. Of the 22,505 households that exited TANF during this period, 146 had multiple spells with at least two exits. The data set we use is centered on exit data, so we do not know how many households exited TANF and returned but didn't exit again before the end of the study period.

- This report provides earnings outcomes for all parents, including those with $0 in earnings, as well as for parents with earnings only. We adjusted all earnings to 2016 dollars using the CPI-U-RS.

Typical annual earnings for parents with earnings in the full cohort rose in the year after exit compared to the year before exit but remained far too low to cover a family’s basic needs. Their median earnings — i.e., earnings directly in the middle of the earnings distribution for parents with earnings only — stood at $9,602, (about 48 percent of the FPL for a family of three), an increase from $5,685 in the year prior to exit (see Table 5).[30]

Every subgroup of parents with earnings experienced an increase in median annual earnings in the year after exit compared to the year before exit, but those gains failed to lift them above the FPL or into an economically secure life. Parents with earnings exiting TANF due to a work sanction had the smallest gains of any subgroup of parents with earnings, and their post-exit median earnings ($6,199) were the second-lowest of any subgroup, slightly above the time limit group ($5,940). The median parent exiting due to work sanctions or time limits had earnings so low that, if annualized on a monthly basis, they would still have qualified financially for cash assistance if not for these policies. They also would have qualified for access to quality work programs that, with adequate state investment,[31] could help them acquire skills for in-demand jobs.

This descriptive study does not look at other supports or resources that may have lifted families' total incomes closer to the poverty threshold, such as tax credits for working families and child support. The vast majority of parents with earnings increases likely saw increases in their income from the Earned Income Tax Credit, a refundable tax credit for families that work but earn low wages so they can better support their children.

| TABLE 5 |

|---|

| Mean and median annual earnings among parents with earnings only, adjusted for inflation, 2016 dollars |

|---|

| Group |

Pre-Exit-Year Earnings |

Post-Exit-Year Earnings |

Absolute Change |

Percentage Change |

|---|

| All Parents with Earnings |

| Mean |

$8,124 |

$12,099 |

$3,975 |

48.9% |

| Median |

$5,685 |

$9,602 |

$3,917 |

68.9% |

| Those Exiting Due to Work Sanctions |

| Mean |

$6,886 |

$8,841 |

$1,955 |

28.4% |

| Median |

$4,194 |

$6,199 |

$2,006 |

47.8% |

| Those Exiting Due to Time Limits |

| Mean |

$5,554 |

$8,238 |

$2,684 |

48.3% |

| Median |

$3,786 |

$5,940 |

$2,154 |

56.9% |

| Those Exiting Due to Excess Earnings |

| Mean |

$11,349 |

$16,927 |

$5,578 |

49.1% |

| Median |

$9,582 |

$15,463 |

$5,881 |

61.4% |

| Those Exiting for Other Reasons |

| Mean |

$7,376 |

$12,046 |

$4,670 |

63.3% |

| Median |

$4,863 |

$9,664 |

$4,801 |

98.7% |