Frequently Asked Questions About Medicaid

End Notes

[1] See also Matt Broaddus and Edwin Park, “Ryan Poverty Report’s Criticism of Medicaid Misrepresents Research Literature,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 31, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4114.

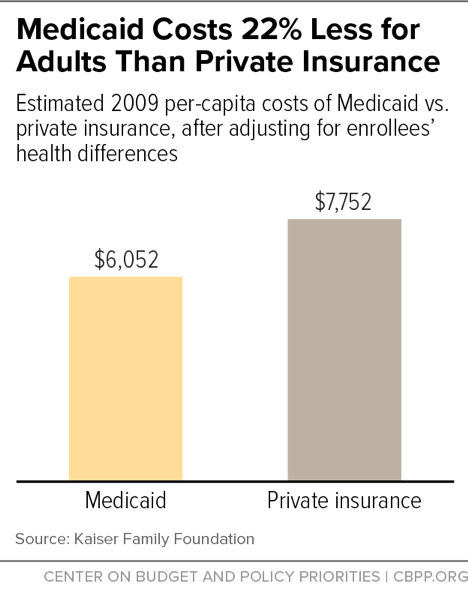

[2] Teresa Coughlin et al., “What Difference Does Medicaid Make? Assessing Cost-Effectiveness, Access and Financial Protection under Medicaid for Low-Income Adults,” Kaiser Family Foundation, May 3, 2013, http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-difference-does-medicaid-make-assessing-cost-effectiveness-access-and-financial-protection-under-medicaid-for-low-income-adults/.

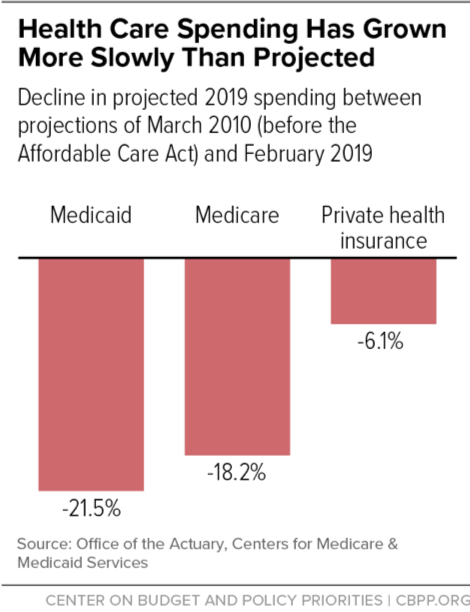

[3] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP,” June 2016, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Trends-in-Medicaid-Spending.pdf.

[4] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid Delivery System and Payment Reform: A Guide to Key Terms and Concepts,” June 2015, http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-delivery-system-and-payment-reform-a-guide-to-key-terms-and-concepts/.

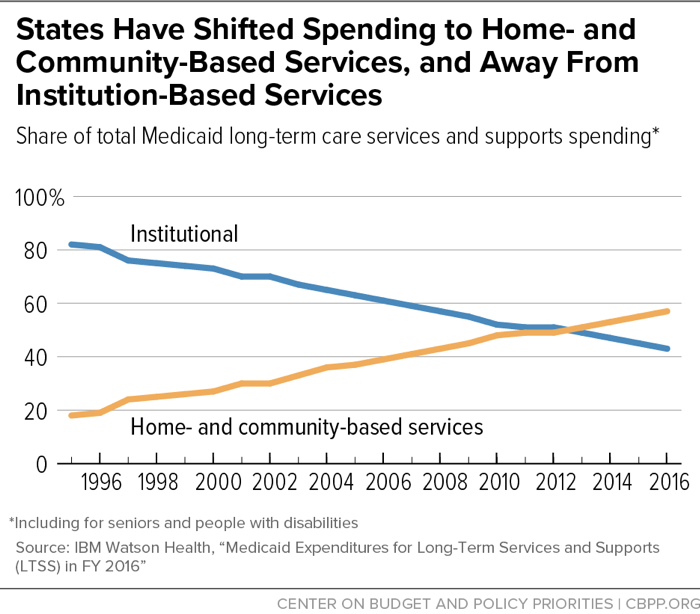

[5] Erica L. Reaves and MaryBeth Musumeci, “Medicaid and Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer,” Kaiser Family Foundation, December 15, 2015, http://kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer/.

[6] Steve Eiken et al., “Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2016,” Truven Health Analytics, May 2018, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/ltss/downloads/reports-and-evaluations/ltssexpenditures2016.pdf.

[7] Hannah Katch, “States are Using Flexibility to Create Successful, Innovative Medicaid Programs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 13, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-are-using-flexibility-to-create-successful-innovative-medicaid-programs.

[8] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Targeting Medicaid Super-Utilizers to Decrease Costs and Improve Quality,” CMCS Information Bulletin, July 24, 2013, http://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/CIB-07-24-2013.pdf.

[9] Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, “Health Care Innovation Awards Round Two Project Profiles,” July 2014, https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/HCIATwoPrjProCombined.pdf.

[10] Christine Schindler, “Complex Care Medical Services: Inpatient Outpatient, and Homecare Focused Patient Management Model,” presentation at 38th National Conference on Pediatric Health Care, March 2017, https://www.melnic.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Advanced-Practice-Provider-Complex-Care-Models-and-Roles.pdf; John B. Gordon et al., “A Tertiary Care-Primary Care Partnership Model for Medically Complex and Fragile Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs,” JAMA Pediatrics, October 2007.

[11] State of Oregon, 1115 Waiver Demonstration Renewal, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/or/Health-Plan/or-health-plan2-ext-appvl-01122017.pdf.

[12] Sarah Klein, Douglas McCarthy, and Alexander Cohen, “Health Share of Oregon: A Community-Oriented Approach to Accountable Care for Medicaid Beneficiaries,” Commonwealth Fund, October 2014, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/case-study/2014/oct/1769_klein_hlt_share_oregon_aco_case_study.pdf.

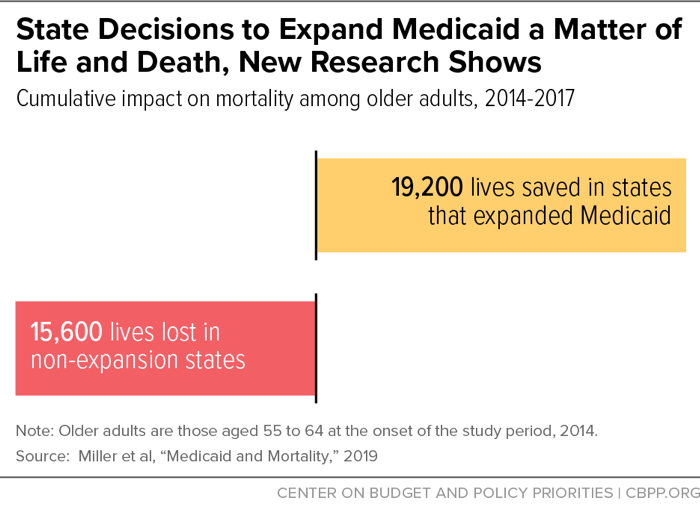

[13] Sarah Miller et al., “Medicaid and Mortality: New Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 26081, August 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26081.

[14] Matt Broaddus and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Medicaid Expansion Has Saved At Least 19,000 Lives, New Research Finds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 6, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-expansion-has-saved-at-least-19000-lives-new-research-finds.

[15] Larisa Antonisse et al., “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 28, 2018, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/.

[16] Miller et al., op. cit.

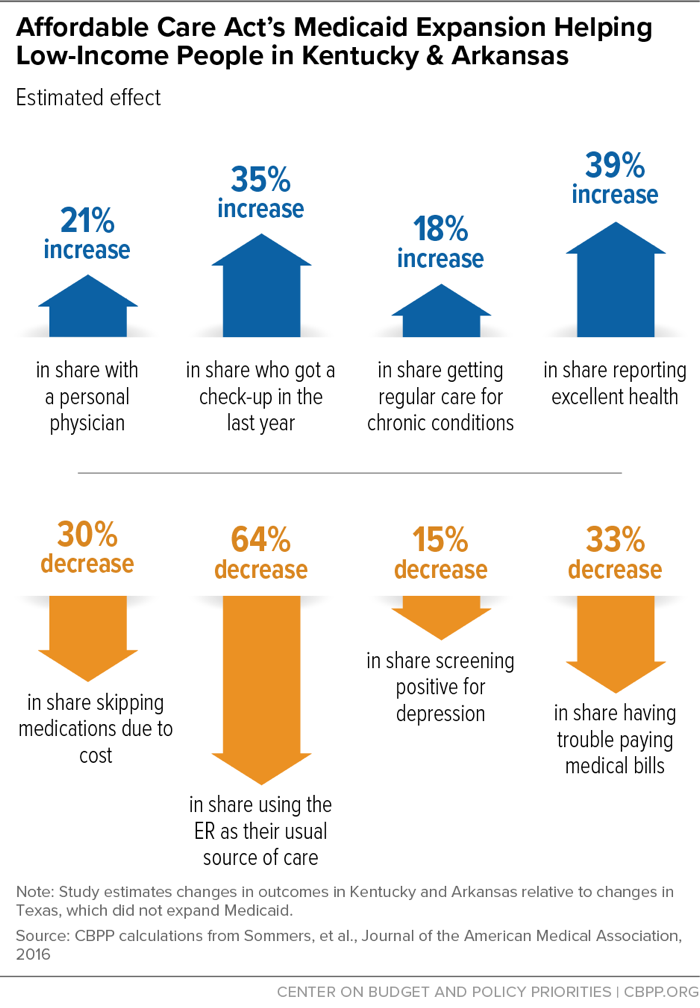

[17] Benjamin Sommers et al., “Changes in Utilization and Health Among Low-Income Adults After Medicaid Expansion or Expanded Private Insurance,” JAMA Internal Medicine, August 8, 2016, http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2542420.

[18] Amy Finkelstein et al., “The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 17190, July 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17190. See also Judith Solomon, “Does Medicaid Matter? New Study Shows How Much,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 7, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/does-medicaid-matter-new-study-shows-how-much.

[19] Katherine Baicker et al., “The Oregon Experiment — Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes,” New England Journal of Medicine, May 2, 2013, 368:1713-1722.

[20] Baicker et al., op. cit.

[21] Benjamin Sommers, Katherine Baicker, and Arnold Epstein, “Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions,” New England Journal of Medicine, September 13, 2012, 367:1025-1034.

[22] Coughlin et al., op. cit.

[23] “MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book,” Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, December 2016, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/MACStats_DataBook_Dec2016.pdf. See also David Blumenthal et al., “Does Medicaid Make a Difference? Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2014,” Commonwealth Fund, June 2015, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2015/jun/1825_blumenthal_does_medicaid_make_a_difference_ib_v2.pdf.

[24] Munira Z. Gunja et al., “How Medicaid Enrollees Fare Compared with Privately Insured and Uninsured Adults,” Commonwealth Fund, April 2017, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2017_apr_gunja_how_medicaid_enrollees_fare_ib.pdf.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Bruce Meyer and Laura Wherry, “Saving Teens: Using a Policy Discontinuity to Estimate the Effects of Medicaid Eligibility,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18309, August 2012, http://www.nber.org/papers/w18309.pdf.

[27] Matt Broaddus, “Medicaid’s Long-Term Earnings and Health Benefits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 12, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaids-long-term-earnings-and-health-benefits. See also Sarah Cohodes et al., “The Effect of Child Health Insurance Access on Schooling: Evidence from Public Insurance Expansions,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 20178, May 2014, http://www.nber.org/papers/w20178.pdf.

[28] Hannah Katch, Jennifer Wagner, and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Taking Medicaid Coverage Away From People Not Meeting Work Requirements Will Reduce Low-Income Families’ Access to Care and Worsen Health Outcomes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 13, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/taking-medicaid-coverage-away-from-people-not-meeting-work-requirements-will-reduce.

[29] Rachel Garfield et al., “Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work: What Does the Data Say?” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 8, 2019, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-intersection-of-medicaid-and-work-what-does-the-data-say/.

[30] Ammar Farooq and Adriana Kugler, “Beyond Job Lock: Impacts of Public Health Insurance on Occupational and Industrial Mobility,” NBER, March 2016, https://www.nber.org/papers/w22118.pdf.

[31] For more information on the effects of taking coverage away from people who don’t meet work requirements, see Jennifer Wagner and Judith Solomon, “States’ Complex Medicaid Waivers Will Create Costly Bureaucracy and Harm Eligible Beneficiaries,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 23, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-complex-medicaid-waivers-will-create-costly-bureaucracy-and-harm-eligible; Hannah Katch, Jennifer Wagner, and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Taking Medicaid Coverage Away From People Not Meeting Work Requirements Will Reduce Low-Income Families’ Access to Care and Worsen Health Outcomes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 13, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/taking-medicaid-coverage-away-from-people-not-meeting-work-requirements-will-reduce; and Jennifer Wagner and Jessica Schubel, “States’ Experiences Confirming Harmful Effects of Medicaid Work Requirements,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated October 22, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/12-18-18health.pdf.

[32] Benjamin Sommers et al., “Medicaid Work Requirements — Results from the First Year in Arkansas,” New England Journal of Medicine, June 2019, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsr1901772.

[33] National Health Law Program, “Federal Court Rules Against Trump Administration’s Kentucky and Arkansas Medicaid Waiver Projects That Include Work Requirements,” March 27, 2019, https://healthlaw.org/news/federal-court-rules-against-trump-administrations-kentucky-and-arkansas-medicaid-waiver-projects-that-include-work-requirements/.

[34] Sommers 2019, op cit.

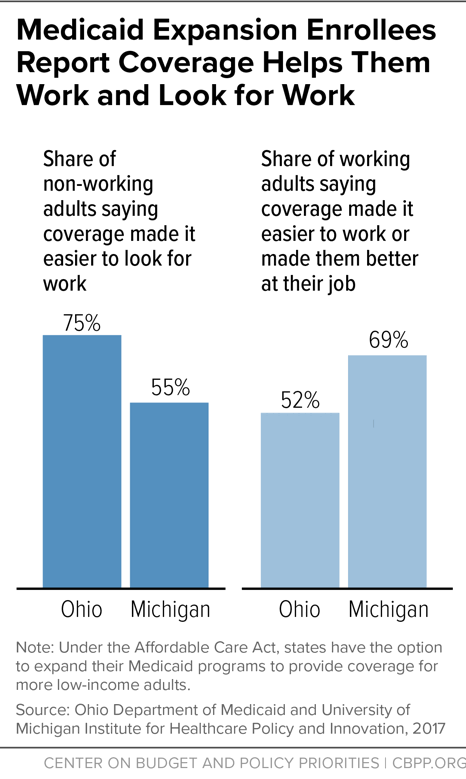

[35] Ohio Department of Medicaid, “Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment: A Report to the Ohio General Assembly,” January 2017, http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Annual/Group-VIII-Assessment.pdf. See also Kara Gavin, “Medicaid Expansion Helped Enrollees Do Better at Work or in Job Searches,” University of Michigan Health Lab, June 27, 2017, http://labblog.uofmhealth.org/industry-dx/medicaid-expansion-helped-enrollees-do-better-at-work-or-job-searches.

[36] Larisa Antonisse et al., “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 2019, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-brief-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-under-the-ACA-Findings-from-a-Literature-Review.

[37] Martha Heberlein et al., “Getting Into Gear for 2014: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP, 2012-2013,” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2013, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/getting-into-gear-for-2014-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-of-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-in-medicaid-and-chip-2012-2013/.

[38] Congressional Budget Office, “Labor Market Effects of the Affordable Care Act: Updated Estimates,” February 2014, http://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/45010-breakout-AppendixC.pdf.

[39] Angshuman Gooptu et al., “Medicaid Expansion Did Not Result In Significant Employment Changes Or Job Reductions In 2014,” Health Affairs, Vol. 35, No.1, January 2016, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/1/111.full.html.

[40] Robert Kaestner et al., “Effects of ACA Medicaid Expansions on Health Insurance Coverage and Labor Supply,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21836, December 2015, http://www.nber.org/papers/w21836.

[41] Jesse Cross-Call, “Medicaid Expansion Continues to Benefit State Budgets, Contrary to Critics’ Claims,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 9, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/health/medicaid-expansion-continues-to-benefit-state-budgets-contrary-to-critics-claims.

[42] Mark Hall, “Do states regret expanding Medicaid?” Brookings Institution, March 26, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/usc-brookings-schaeffer-on-health-policy/2018/03/26/do-states-regret-expanding-medicaid/.

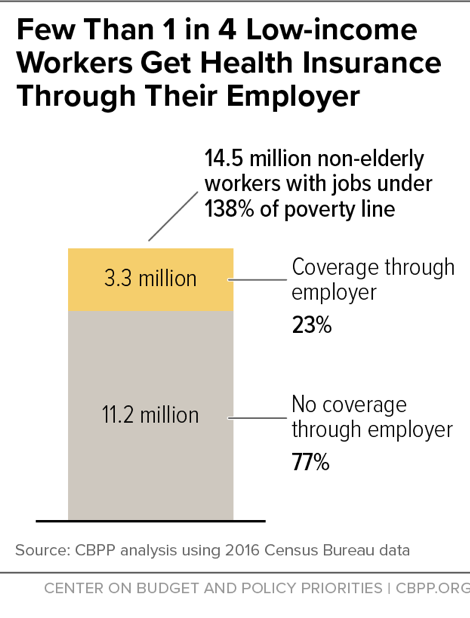

[43] Adele Shartzer, Fredric Blavin, and John Holahan, “Employer-Sponsored Insurance Stable For Low-Income Workers In Medicaid Expansion States,” Health Affairs, Vol. 37, No. 4, April 2018, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1205.

[44] Jennifer Haley et al., “Uninsurance and Medicaid/CHIP Participation among Children and Parents,” Urban Institute, September 2018, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99058/uninsurance_and_medicaidchip_participation_among_children_and_parents_updated_1.pdf.

[45] Government Accountability Office, “Means-Tested Programs: Information on Program Access Can Be an Important Management Tool,” March 2005, http://www.gao.gov/assets/250/245577.pdf.

[46] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Total Medicaid Enrollees – VIII Group Break Out Report, 2017, 3Q, August 2018, https://data.medicaid.gov/Enrollment/2017-3Q-Medicaid-MBES-Enrollment/rxbg-jqed..

[47] Haley et al., op. cit.

[48] Dahlia Remler and Sherry Glied, “What Other Programs Can Teach Us: Improving Participation in Health Insurance Programs,” American Journal of Public Health, January 2003, http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.93.1.67.

[49] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Faces of the Medicaid Expansion: Experiences of Uninsured Adults Who Could Gain Coverage,” November 2012, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/faces-of-the-medicaid-expansion-experiences-and/.