- Home

- Research Note: Contrary To Maine Officia...

Research Note: Contrary to Maine Officials’ Claims, TANF Time Limit Leaves Most Families Without Work or Cash Assistance

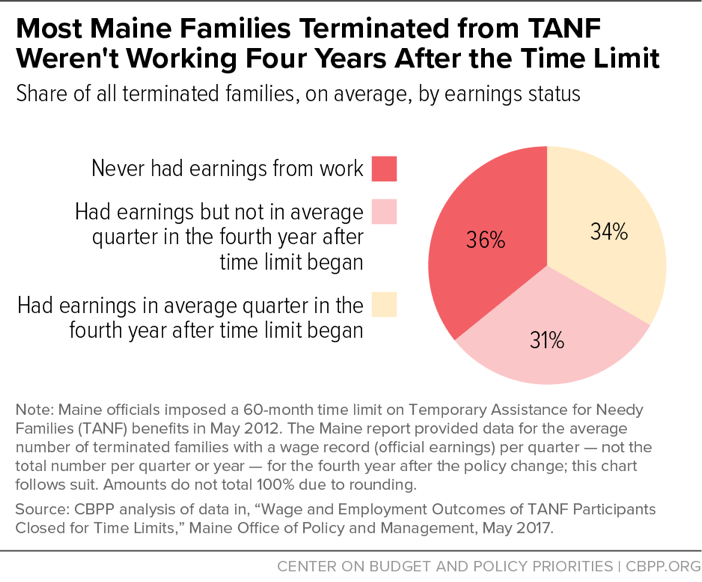

A recent state-issued report in Maine touts the purported success of imposing a five-year time limit on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance for families,[1] despite data in the report showing that in any quarter, on average, in the fourth year after the policy change was implemented, two-thirds of terminated families did not work. The report claims that, due to the TANF time limit, employment and earnings grew and the families subject to the time limit are faring better — but that was not the experience for the average family that lost cash assistance that helped them to meet their basic needs.

The recent report examines work rates and earnings among the 1,856 families who were immediately terminated from TANF in the second quarter of 2012 when the time limit was imposed, but it does so in a way that distorts the key findings. State officials reviewed data over a five-year period from the second quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2016, or from one year before the time-limit implementation to four years after termination. The report has three major flaws: it covers up the extent to which terminated families are not working; praises earnings growth even when earnings are stuck far below the poverty level; and has methodological problems and leaves key questions unanswered.

The methodologically flawed report cherry picks data and omits key findings.The methodologically flawed report cherry picks data and omits key findings — such as how 1 in 3 of the terminated families never had earnings during the study period — to position the time limit as a positive policy change. It hides facts that show that most families that reached the time limit have not been able to replace the cash assistance they lost with income from work, putting the children in these families at great risk of experiencing high levels of deprivation and stress, which have lifelong negative consequences.

This report comes on the heels of a discredited 2016 report the state issued about the results of imposing a time limit in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.[2] Both reports appear to be a public relations effort aimed at defending harsh policies designed to scale back basic needs programs that help families make ends meet until they can get back on their feet.

The report covers up the extent to which terminated families were not working.

Approximately 2 in 3 of all terminated families, on average, did not work in any given quarter in the fourth year after the state implemented the policy (see Table 1 and Figure 1). More than half of those not working in any given quarter in the fourth year had no earnings from work during the entire study period. This means that once state officials cut them from TANF, they had neither TANF cash assistance nor earnings from employment over the next four years. The remaining share of those not working in the fourth year worked at some other point during the study period but not at any point in the study’s final year.

| TABLE 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vast Majority of Maine Families Terminated from TANF Had No Earnings Four Years After State Officials Imposed the Time Limit | |||

| Earnings Status During 5-Year Study Period | Number | Share of Total | Share of Those with Earnings |

| Total Terminated Families | 1,856 | / | / |

| Never Had Earnings | 663 | 35.7% | / |

| Had Earnings | 1,193 | 64.3% | / |

| Had Earnings Before Policy Change | 541 | 29.1% | 45.3% |

| First Had Earnings After Policy Change | 652 | 35.1% | 54.7% |

| Earnings Status in Average Quarter in Fourth Year of Policy | Number | Share of Total | Share of Those Without Earnings |

| Total Terminated Families | 1,856 | / | / |

| Average Number Without Earnings | 1,232 | 66.4% | / |

| No Earnings -- Worked but Not in Average Quarter in Fourth Year | 569 | 30.7% | 46.2% |

| No Earnings -- Never Worked During Entire Study Period | 663 | 35.7% | 53.8% |

| Average Number With Earnings | 624 | 33.6% | / |

Note: Earnings status data comes from the Maine Department of Health and Human Services and Maine Unemployment Insurance wage system. The dataset captures workers with a wage record (official earnings) on file (almost every wage and salary job in Maine).

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ analysis of data in, “Wage and Employment Outcomes of TANF Participants Closed for Time Limits,” Maine Office of Policy and Management, May 2017.

The report obscures these findings, however, by not presenting data for the whole group of terminated families. Instead, it primarily focuses on those who were able to find work and uses data to contend that the time limit had an overall positive effect on work and earnings, when the truth is that many families had no earnings, and among those who did, earnings were sporadic at best.

The Administration’s press release accompanying the report[3] praises the growth in the number of individuals employed, without presenting that growth within the broader context of all terminated families. For example, it highlights that there was an 84 percent increase in the average number of people working in any given quarter during the fourth year of the time limit compared to the year before the time limit. While that growth is a move in the right direction, the average number of families that gained employment was small over that period: just 285 families, or about 15 percent of all those terminated. To put this in perspective, it is important for the reader to know that 663 terminated families never had earnings during the entire study period.

How Maine Makes the Employment Results of Families Terminated by Its TANF Time Limit Look Far Better Than They Are

Maine’s report obscures certain outcomes by not presenting data for the whole group of families that the state terminated from TANF. It puts a positive spin on the data by presenting a mix of earnings indicators (total earnings, average quarterly earnings, and the number or average number with earnings) for select groups of terminated families over different comparison periods.

- The report categorizes the terminated families into two major groups: those who had earnings any time during the five-year period and those who never had earnings, but focuses its analysis only on those with earnings. Among those who ever worked, it presents data for the year before the policy change and for the fourth year after the policy change.

- The report also creates subgroups among those who ever worked during the five-year study period: those who had earnings the year before the policy change and those who did not have earnings that year. It presents data for the quarter the policy change began and for the same quarter three years later. (This is a different comparison period than the other two analyses described in in the first and third bullets.)

- The report creates another set of subgroups among those who ever worked during the five-year study period: those who were on TANF for five to six years and those who were on TANF for seven or more years. It presents data for the earnings indicators for both subgroups for the year before the policy change and for the fourth year after the policy change.

Within each of the three subgroups, the report never presents earnings data across all terminated families — i.e., the average and total earnings outcomes exclude data for those without earnings, which is out of step with how most rigorous longitudinal studies examine the impact of policy changes. This method masks the complete picture of terminated families’ experiences. Moreover, these subgroups are not true comparison groups, meaning that any increases in earnings could have resulted from other changes, such as a greatly improving economy, and cannot be attributed to the policy change.

The report praises earnings growth even when few families worked consistently and earnings remained far below the poverty level, falling short of what families needed to make ends meet.

As more terminated families worked over the study period, the report highlights the fact that total earnings increased from $2.6 million in the year before the time limit began to $8.6 million four years after. Maine’s economy, like the nation’s, was improving during the time this evaluation occurred so we would have expected earnings gains even without a policy change, although we do not know of what magnitude. In addition, this earnings growth appears to have been concentrated among a small share of families subject to the time limit.

To estimate earnings gains during the study period for the average terminated family, standard procedure would be to include earnings for all of the 1,856 families who were the subject of the study in the calculation — that is, earnings both from those that found work and those that did not (i.e., those with $0 in earnings). Using this methodology, the average earnings of $4,634 in 2015 ($386 per month) was only 23 percent of the federal poverty level for a one-parent, two-child household (the typical size of a Maine TANF household). While this is more than the average earnings of $1,401 that families received before the time limit, it’s nearly $1,200 less than what families would have received in cash assistance if they had continued to be eligible for TANF benefits.[4]

Income that falls short of the federal poverty level is especially concerning because this threshold was designed to determine the minimum income necessary for a family to survive, not to be economically secure. Inadequate family income can be detrimental to children’s ability to succeed long-term in a range of areas, such as school and health.[5]

While the Maine report suggests that some families did have more income after the time limit policy was implemented, even those families were not earning enough to meet their basic needs. For terminated families with earnings in any given quarter, the report indicates average quarterly earnings increased over the five-year study period, from $1,884 in the year before the time limit began to $3,459 four years later — or by $1,575. In 2015, the average earnings of $3,459 were only 69 percent of the federal poverty level (on a quarterly basis for a one-parent, two-child household). Moreover, the data suggest that most parents with earnings four years after the start of the time limit were unlikely to have annual earnings that reached close to this level as this would have required this same amount of earnings in every quarter, but just one-third of the families worked in any given quarter that year.

Despite the data showing otherwise, Mary Mayhew, Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services Commissioner at the time of the report’s release, said, “These findings further validate the message this Department promotes — the best way out of poverty is a job.”[6] But on closer reflection, that’s not what the findings illustrate for the average terminated family. While jobs that pay livable earnings (for those who can work and when jobs are available) can lift families out of poverty, the data in the report show that even the terminated families who had earnings, on average, were not earning enough to make ends meet.

The report has methodological problems and leaves key questions unanswered.

There is no way to know what terminated families’ work rates and earnings would have been without the implementation of the time limit. The report acknowledges that the state hasn’t done the rigorous research that is needed to untangle the effects of the time limit on work rates and earnings from the improving economy or other factors. “Further analysis would be required to identify the causal factors underlying the changes in employment outcomes reported in this study,” the report notes.

While the study often compares the TANF families to the broader labor force, such a group is not a true “control group” by any rigorous standard. The report also compares fractions of the terminated families against one another — those that worked before the time limit versus those that didn’t but ended up working by the end of the study period, for example — but those aren’t true comparison groups either. A valid comparison group study would have compared the experiences of those subject to the time limit to an otherwise comparable group not subject to the time limit. Without a meaningful control group, any increases in employment or earnings cannot be attributed to the policy change. This is especially true during a time when an improving economy could produce the same result.

Because this report fails to build scientifically valid evidence about how the time limit affects work rates and earnings among needy families, it is irresponsible to use the findings to praise the policy change, especially when most families either never worked or weren’t working, on average, in any given quarter by the end of the study.

Conclusion

TANF serves a diverse group of families, with some having strong attachment to the labor force and others facing significant personal and family challenges that limit their employment prospects. In an effort to obscure the reality of what happened after Maine officials implemented the time limit, this report focuses on the minority of terminated families who had some earnings after the time limit went into effect and ignores the fact that most terminated families were unable to replace the steady income they received from TANF with earnings. These are the very families that would benefit most from the services that TANF is supposed to provide to help families make the successful transition to employment. A fuller examination of the data shows that implementation of the time limit is not the policy success that the officials in Maine claim it to be.

SNAP Reports Present Misleading Findings on Impact of Three-Month Time Limit

Increases in TANF Cash Benefit Levels Are Critical to Help Families Meet Rising Costs

Policy Basics

Income Security

End Notes

[1] “Wage and Employment Outcomes of TANF Participants Closed for Time Limits,” (Maine) Governor’s Office of Policy and Management, May 25, 2017, http://www.maine.gov/economist/docs/TANF%20Report%20Final%205-25-17.pdf.

[2] Dorothy Rosenbaum and Ed Bolen, “SNAP Reports Present Misleading Findings on Impact of Three-Month Time Limit,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 14, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-reports-present-misleading-findings-on-impact-of-three-month-time.

[3] “After Implementation of Time Limits, Former TANF Recipients Experienced Increase in Wages,” Maine Government News, May 25, 2017, http://www.maine.gov/tools/whatsnew/index.php?topic=Portal+News&id=755014&v=article-2017.

[4] Assumptions based on maximum benefit levels for a family of three in Maine. For benefit levels, see Ife Floyd, “Policy Brief: TANF Cash Benefits Are Too Low to Help Families Meet Basic Needs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 2, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/policy-brief-tanf-cash-benefits-are-too-low-to-help-families-meet.

[5] Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson, “The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty,” Pathways (Winter 2011), http://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/PathwaysWinter11_Duncan.pdf.

[6] Ibid.