The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic crisis have brought to light the fundamental role housing plays in people’s lives and the life and death implications when they cannot afford the rent. Even before the pandemic, millions of individuals and families were homeless or struggling to pay the rent; the health and economic crises have deepened these problems. Recognizing this, policymakers must include comprehensive housing assistance in the next COVID-19 relief package, prioritizing aid for people with the most severe housing needs.

The pandemic has resulted in serious consequences for those with the fewest resources:

- For people without homes and living on the streets or in emergency shelters, the pandemic has increased health risks and compounded communities’ challenges in helping them to find safe and stable housing.

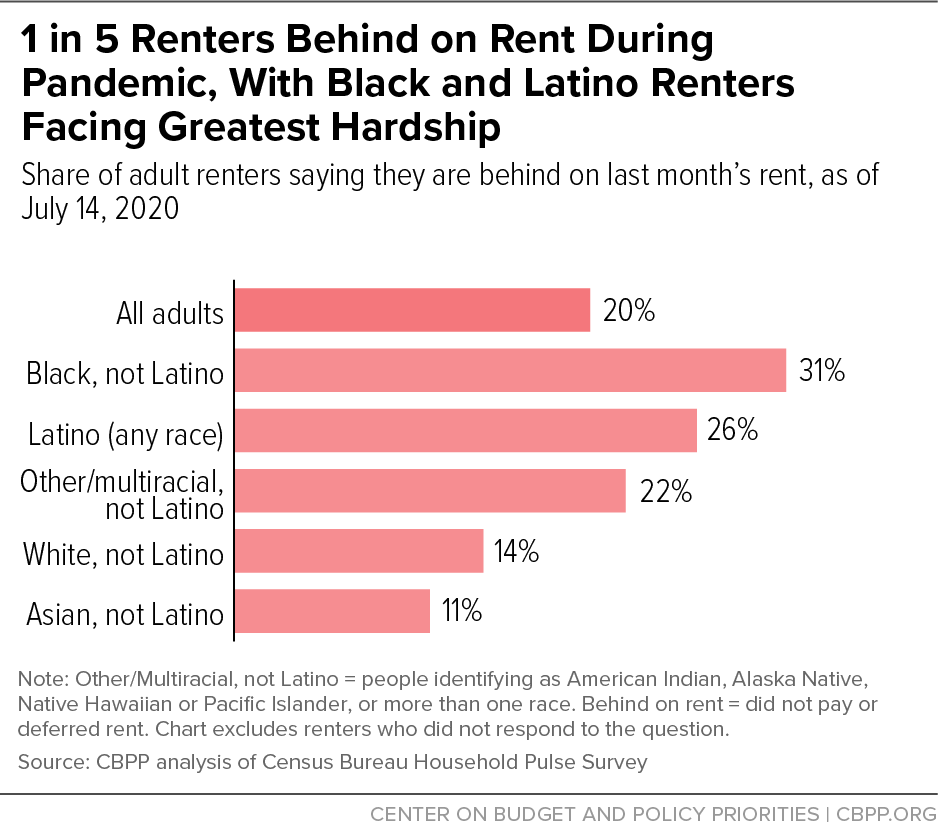

- Nearly 14 million adults in rental housing — 1 in 5 adult renters — are currently behind in their rent payments, according to Census data, and temporary eviction moratoriums that protect some renters from eviction have begun to expire. Difficulties paying rent are particularly prevalent for Black and Latino renters, 31 percent and 26 percent of whom, respectively, reported in early July that they had fallen behind on rent, compared to 14 percent of non-Hispanic white renters and 11 percent of Asian renters.[1] Moreover, large numbers of renters are struggling to pay rent despite the expansion of and weekly increase in unemployment benefits that Congress authorized in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

- Income losses among assisted tenants are also straining federal rental assistance programs, creating budget shortfalls that will force cuts in the number of families, seniors, and others with assistance at a time when growing numbers of unassisted households are likely struggling to pay the rent.

To be effective, interventions must be tailored to address each of these housing problems. The CARES Act included provisions to mitigate some of these problems, but funding is too low and several of its key provisions will expire this month, well before the health and economic crisis has subsided. If policymakers fail to act, millions of low-income renters and people experiencing homelessness are likely to experience avoidable evictions, continued homelessness, or other preventable hardships.

To provide relief for renters, policymakers should draw on the housing provisions of the House-passed Heroes Act, which together constitute a strong, comprehensive approach to preventing evictions and alleviating other hardship among renters during the pandemic. The key elements of this approach include:

- Housing vouchers to provide long-term housing stability. State and local housing agencies are well positioned to identify individuals and families facing the greatest risks of eviction or homelessness and to provide them with rental vouchers that will help them to remain stably housed for the long term. The system is robust enough to provide emergency vouchers to 500,000 at-risk households over the next year, at a five-year cost of about $26 billion. (The Heroes Act includes $1 billion for this purpose, and two bills, H.R. 7084 and S. 4164, would provide $10 billion.)

- Homelessness assistance. State and local agencies need more funding to expand safe, non-congregate shelter options for people experiencing homelessness, revamp their facilities to prevent the spread of the virus, and provide services to help people remain housed and avoid homelessness. The CARES Act provides $4 billion for these purposes, but analysts have concluded that an additional $11.5 billion will be needed to continue and expand these efforts during the pandemic.

- Eviction prevention. In addition to the need to extend the federal eviction moratorium, policymakers should provide significant funding through the Emergency Solutions Grant program for short- and medium-term rental assistance to help people stay in their current homes, avoid accumulating housing-related debt (without leaving landlords responsible for unpaid rent), and avoid eviction once federal, state, and local moratoriums expire.

- Supplemental funding for rental assistance programs to cover increased subsidy costs caused by tenant income losses. Income losses among currently assisted households are increasing subsidy costs, and many agencies will be forced to cut the number of households they assist if they do not receive additional funding to cover these costs. We estimate that at least $1 billion will be required to address shortfalls in the Housing Choice Voucher program, and additional funds will be needed for public housing and other programs.

In negotiating funding levels, policymakers should prioritize assistance for people with the most severe housing needs, particularly Emergency Housing Vouchers and Emergency Solutions Grants for those experiencing or at high risk of homelessness.

Millions of individuals and families faced significant housing hardships before the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost 11 million low-income households, containing 23 million people, paid over half their income for rent in 2018.[2] The 2019 homelessness assessment found that 500,000 people were homeless during the point-in-time count, and about three times that number spent at least one night in an emergency shelter over the course of the year.[3] Many more people experience other types of housing instability and hardship. For instance, local school officials reported to the Department of Education that an additional 1.1 million school-age children were living either doubled-up with other families or temporarily in hotels or motels because of economic hardship.[4]

The pandemic and its economic fallout have worsened housing affordability issues. Communities are facing new challenges in helping people who are homeless, and income losses are making it even harder for families to pay rent and make ends meet. The crisis has also caused budget shortfalls in existing rental assistance programs that threaten cuts in assistance at a time when more people are at risk.

Addressing these issues in the next relief package will be critical to averting a spike in evictions and homelessness and ensuring that those experiencing homelessness have safe shelter.

Helping people who are experiencing homelessness is always challenging, but the pandemic has multiplied these challenges and made them more urgent to meet. As noted above, roughly 500,000 people were already homeless when the pandemic hit, mostly living either on the street or in congregate shelters that make it very difficult to maintain safe social distancing to reduce COVID-19’s spread.

Business closures also hurt people experiencing homelessness in less obvious ways. People living on the street have trouble finding bathrooms and places to wash their hands. Fewer people in urban areas mean that those who rely on money, leftover food, or other gifts from passersby aren’t able to meet their basic needs. Libraries being closed restricts access to computers and internet services that are often used to find jobs, housing, and general social services.

Racial disparities among people experiencing homelessness are also a concern and must be addressed. Communities of color are over-represented among the homeless population, with Black people comprising 40 percent of all those experiencing homelessness, according to the most recent data.[5]

Resources are needed to help homeless services programs:

- Reconfigure shelter space to improve staff’s and clients’ ability to socially distance;

- Help people who are experiencing homelessness move from the streets or congregate shelters into safer, non-congregate housing, including temporary lodging in hotels and motels;

- Improve health care, prevention, and re-housing services for people experiencing homelessness or at risk of losing their homes in ways that address longstanding disparities that have resulted in people of color being over-represented among those without homes;[6]

- Increase outreach to people living on the street to improve access to health care or other support they may need; and

- Continue efforts to help individuals and families with children quickly move into more stable, permanent housing. Many people temporarily housed in hotels and motels will need rental assistance to avoid returning to living on the street. And there is a justified concern that some communities’ efforts that began prior to the pandemic, like using housing-first strategies[7] to quickly house people experiencing chronic homelessness, people fleeing domestic violence, or people with disabilities leaving institutional care, have stalled or will stall due to an inability to locate affordable long-term housing and housing agencies’ concerns about future rental assistance funding.

The nation has experienced unprecedented job losses over the past several months, and federal government data show that these losses are heavily concentrated among workers who are paid low wages (who are more likely to rent rather than own homes), and that Black and Latino workers have been hit particularly hard.[8]

Barriers to educational and job opportunities substantially influenced by historical and ongoing racist policies and practices have led to Black and Latino workers disproportionately being employed in jobs that pay low wages. The official unemployment rate in June was 15.4 percent for Black workers, 14.5 percent for Latino workers, and 10.1 percent for white workers. And the job market improvement of the last couple of months has disproportionately benefited white workers. Between April and June, unemployment fell by 4.1 percentage points for white workers but just 1.3 percentage points for Black workers. Unemployment has also increased more for foreign-born workers (this group includes people who have become U.S. citizens) than for U.S.-born citizens.

Both the number of people out of work and the number facing challenges affording food have risen markedly because of the current crisis, data from several sources show.[9] While hard data on the trends in the numbers of people facing difficulties paying rent are limited this early into the health and economic crisis, emerging data make clear that millions of renters are struggling. An estimate by Urban Institute researchers finds that 6 million renter households — about 1 in 7 renter households — have experienced job losses since February (losing over $15 billion a month in income), including nearly 3 million low-income households.[10]

Roughly consistent with Urban’s estimates, the Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse survey finds that an estimated 13.8 million adults in rental housing — 1 in 5 renters — were behind on rent in the week ending July 14.[11] (See Figure 1.) These figures include those not paying rent (12.5 million) or having their rent deferred (1.3 million). Other evidence suggests that many families who have managed to pay their rent are doing so by acquiring debt (e.g., using credit cards), which could also have long-term consequences if they have to continue this practice to make ends meet.[12]

Many renters are struggling to pay rent despite the substantial weekly increase in, and expansion of, unemployment benefits that Congress authorized in the CARES Act. Millions of renters are thus falling through the cracks and are at increasing risk of losing their homes unless policymakers make more rental assistance available.

Evictions and other housing instability exacerbate financial hardship and can have other harmful consequences for families over the long term. Loss of housing often causes families with few resources to move into crowded housing with family or friends or to different communities that require their children to change schools, or for those with the fewest resources, even to experience homelessness. Housing insecurity also contributes to long-term stress on parents and children, which can result in an inability to concentrate in school, compromised immune systems, anger management challenges, anxiety, and depression.[13]

The circumstances of the pandemic — including experts’ expectations that the economic downturn is likely to last well into 2021 and maybe 2022 — means that millions of families are likely to continue to struggle to pay rent or to catch up on their rent after they regain their jobs. Programs that provide short- to medium-term (two years or less) rental assistance to cover lost income can significantly reduce this hardship and the risk of eviction, and funding for such assistance is needed in the next package.[14] While short-term assistance can help many households, however, some households — such as people with histories of homelessness, those leaving domestic violence situations, or people with disabilities and housing instability — will likely face housing and employment challenges for several years and need the longer-term assistance provided through housing vouchers.[15]

The steep job losses caused by the economic contraction have also affected working households that use federal rental assistance such as housing vouchers. While most rental assistance recipients are seniors or people with disabilities who rely on Supplemental Security Income and do not work, about 30 percent of assisted households were likely working before the pandemic, and roughly 1 in 6 of those working households may have lost jobs in recent months, consistent with the spike in unemployment among low-wage households.[16] Federal rules protect assisted households that have lost income by allowing them to request a proportional reduction in their rent payment. When the rent payment is reduced, the federal subsidy increases to fill the gap.

The increased demand for rent adjustments is straining housing agency budgets and increasing the need for supplemental program funding. We estimate that, for the housing voucher program alone, for example, between $1.15 billion and $1.85 billion in additional subsidy funding may be needed in 2020 and 2021 to make up for job losses among assisted tenants. If policymakers do not provide sufficient additional subsidy funding to close these gaps, housing agencies and others that administer federal rental assistance will be forced to cut the number of households they assist, with the result that tens or even hundreds of thousands fewer families, seniors, and others would receive rental assistance in coming months despite a surge in the number of households struggling to pay rent and avoid eviction. A $1.0 billion shortfall would result, for example, in about 100,000 fewer households receiving rental assistance.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the CARES Act, both enacted in March, include important measures that have shored up household incomes and reduced hardship.[17] These include: expanded unemployment benefits; direct stimulus payments through the IRS; increased nutrition benefits for some SNAP recipients (though not the poorest households); replacement benefits for children losing school meals; an eviction moratorium on most federally subsidized properties; and funding for homelessness services and prevention.

In particular, the CARES Act’s expanded jobless benefits have mitigated hardship for millions of workers, and the Act’s moratorium on evictions in federally subsidized housing (as well as other state and local eviction moratoriums) has protected many renters, including some who were struggling to pay rent before the pandemic.[18] The CARES Act also included $4 billion for homeless services and temporary housing, and communities have done an excellent job so far responding to the needs of people experiencing homelessness. Hotels and motels are being used as temporary housing, shelters are being redesigned, and cities have halted local sweeps that typically disperse people living on the street, making it harder to serve them.

The temporary resources and protections provided in the Families First and CARES Acts were only a first step, however, and they are far from adequate for the long-lasting economic downturn that is now projected. Many people who are out of work or who have seen a loss of income are being left out, and, as the evidence cited above shows, millions are falling behind on their rent. Moreover, the temporary eviction moratoriums that have protected many renters from eviction have begun to expire.[19] We also know from past recessions that even if the health pandemic ends in 2021, economic recovery takes time and is often slower for low-paid workers, particularly low-paid workers of color, than for higher-income people.[20] Therefore, more resources are needed to avert harmful outcomes for people with the most severe needs.

There isn’t just one type of renter problem, but several of differing severity, and to address them effectively, policymakers must design and allocate renter relief appropriately. As House and Senate negotiations on the next COVID-19 relief package begin, policymakers must prioritize housing assistance resources for those facing the most severe challenges, specifically people experiencing or at high risk of homelessness. They can do this through both direct homelessness assistance and the Housing Choice Voucher program, while also including eviction prevention resources and supplemental funds to protect federal rental assistance recipients.

Specifically, Congress should invest:

-

$26 billion for 500,000 emergency housing vouchers. For people who are homeless or renters who have the greatest risk of eviction and homelessness, long-term rental assistance such as a housing voucher is much more likely than short-term rental assistance to provide the stability that can be essential to reducing hardship and helping them to get back on their feet.[21] For renters, unpredictable factors such as illness or job losses can trigger eviction and homelessness, but underlying factors can significantly increase their chances of ending up in an emergency shelter. These factors include a history of poverty and housing instability (including prior episodes of homelessness), living doubled up with other families due to economic hardship, having high levels of debt or rent arrears, having already received an eviction notice, being pregnant or having young children, or attempting to flee domestic violence.[22] Not only are housing vouchers the most effective form of aid for people with the most severe housing challenges; they have a proven record of reaching Black and other people of color, who are experiencing hardship in disproportionate numbers during the pandemic.[23]

Additional rental vouchers would enable communities to reduce the number of people currently experiencing homelessness, including the number who have experienced long or repeated bouts of homelessness. But many more individuals and families who are at risk of eviction and eventual homelessness would also benefit from emergency housing vouchers.

State and local housing agencies are well positioned to identify individuals and families facing the greatest risks of eviction or homelessness and provide them with rental vouchers that will help them to remain stably housed for the long term. The system is robust enough to provide emergency vouchers to 500,000 at-risk households over the next year, if adequate funding is provided. Under this approach, the 500,000 emergency housing vouchers would remain available to the recipient households so long as they need them to remain stably housed. Funding of $26 billion would fund these vouchers for five years, allowing them to remain available without further congressional action or funding.[24] (Sen. Sherrod Brown and Rep. Maxine Waters have introduced bills to provide $10 billion for approximately 200,000 emergency housing vouchers — also five-year funding — while the Heroes Act includes $1 billion of one-year funding for roughly 100,000 new housing vouchers.)

-

$11.5 billion for homeless assistance through the Emergency Solutions Grant program. The CARES Act provided $4 billion for this purpose, but communities need an additional $11.5 billion to provide adequate shelter for homeless people during the pandemic, as experts recommended in March, as well as to provide aid to at-risk renters to prevent them from becoming homeless.[25] Additional resources would help homelessness service providers do more to reconfigure shelters and expand housing options to make adhering to social distancing guidance possible, serve people with complex needs such as those with behavioral health conditions or those exiting jails and prisons, and provide short-term assistance to prevent homelessness.

Emergency Solutions Grants are flexible resources that communities may use to provide temporary shelter, support services, and short- or medium-term (up to 24 months) rental assistance to people experiencing homelessness.

-

Funding dedicated to eviction prevention. As explained above, short- and medium-term rental assistance is a key part of any comprehensive strategy to reduce evictions and hardship among low- and moderate-income households. These resources are especially urgent given the impending expirations of federal, state, and local eviction moratoriums. The Heroes Act provides substantial funding to provide short- and medium-term (up to 24 months) rental assistance (via the Emergency Solutions Grant program) to low-income households that are struggling to keep up with the rent.

The Heroes Act also would extend and expand both the federal eviction moratorium and some mortgage relief provisions to help landlords. These are short-term solutions that would protect people living in the covered properties but would not prevent renters from accruing housing-related debt. Ongoing rental assistance and funding for eviction prevention, coupled with provisions like expanded jobless benefits that boost household income, are necessary to help people pay their rent and remain housed over the longer term.

- Funds to protect rental assistance programs. Department of Housing and Urban Development-assisted households that have lost income may request a reduction in their rent payment so that they pay no more than 30 percent of their income towards rent. When the rent payment is reduced, the subsidy paid by local housing agencies increases to fill the gap. We estimate that $1 to $2 billion is needed to cover these cost increases.

Investments in homeless services and rental assistance programs positively affect the lives of millions of people with low incomes. Housing vouchers and other rental assistance end homelessness for thousands of people each year and lift millions out of poverty, improve outcomes for children, and improve overall well-being for adults.[26] This evidence underscores the importance of incorporating investments in homelessness services and rental assistance as part of the next COVID-19 relief package.