BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Solutions to Homelessness Within Reach Regardless of Supreme Court Ruling in Upcoming Case

Homelessness has risen to historic levels, and the Supreme Court is about to weigh in on whether communities can fine or jail people for sleeping outside when they have nowhere safe to go. But evidence shows that we can solve homelessness if we address its primary driver: the gap between incomes and rents. Expanding rental assistance is a highly effective way to close that gap. Policymakers must also sustainably fund the supportive services people need to find and keep housing.

Housing is a basic human need, but it’s out of reach or hard to keep for far too many people. This is a policy choice, not an economic inevitability. Millions of people’s income from low-paid jobs and public benefits are too low to meet their basic needs. Even if landlords and property owners charged rents that only covered the minimum costs to pay their bills and maintain and operate safe, healthy properties, the rents would still be unaffordable for too many people.

This reality has caused the gap between rent prices and many renters’ incomes to persist for decades. Even in periods when rent rises slowly, incomes haven’t caught up. And efforts to supplement people’s incomes to fill that gap don’t reach all those who need it. For years, federal rental assistance has consistently only reached about 1 in 4 eligible households due to underfunding. While funding for the voucher program has risen in most years, that’s barely been enough to account for rising rent costs.

In the absence of assistance, millions of people with low incomes scrape by each month and frequently face eviction, causing moves that disrupt their lives. Hundreds of thousands of people are forced into homelessness each year. About 8.53 million low-income renter households pay more than half their income on rent or live in poor-quality housing, or both.

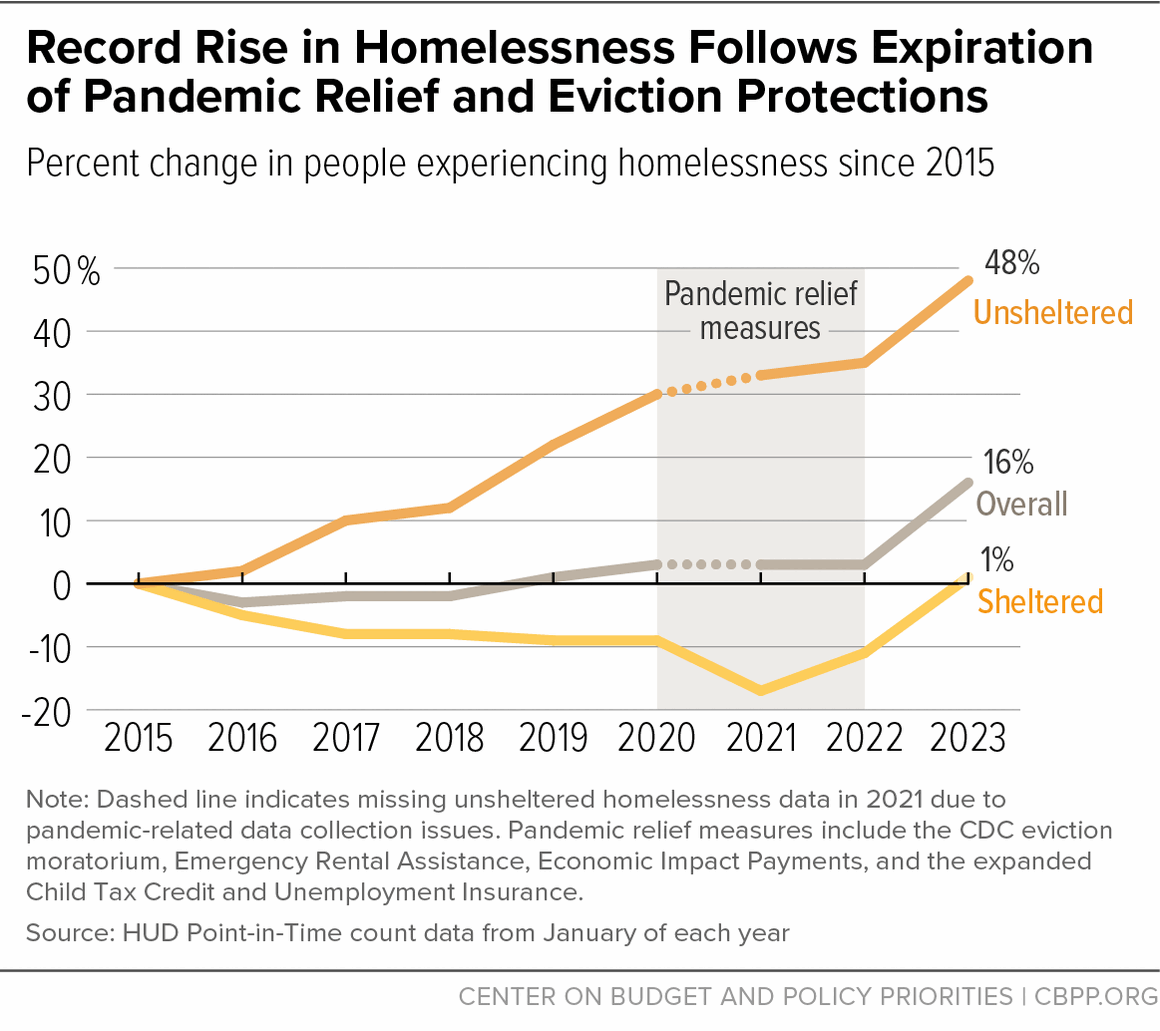

In addition to widespread housing instability, homelessness has risen well above pre-pandemic levels as temporary pandemic assistance has largely expired and the gap between renters’ incomes and rent costs has persisted. (See graphic.)

On a given night in January 2023, over 650,000 people were unhoused, an all-time high since this measure was first reported in 2007. The recent rise in homelessness has been concentrated among those who are unsheltered. (The shelter population fell during the pandemic as other forms of housing assistance were used to reduce shelter populations.)

Unfortunately, some policymakers are responding to homelessness with coercive and harmful practices instead of scaling up what works. People experiencing unsheltered homelessness are often the main target.

For instance, the city of Grants Pass, Oregon passed a law that purported to ban “camping” but effectively made it illegal for people to sleep outside with as a little as a blanket or cardboard box for protection even though they have nowhere safe to go. The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on April 22 and will issue a decision by the end of June about whether this practice is cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment.

We can’t fine or arrest our way out of homelessness. In fact, these and similar practices make it harder for people to gain permanent housing and drain resources from the real solutions — rental assistance and supportive services. No matter how the Supreme Court rules, federal, state, and local policymakers must prioritize the safety of unhoused people and commit to evidence-based solutions.

Rental assistance, such as housing vouchers, provides long-term stability because it covers the gap between what people can afford to pay toward housing costs — around 30 percent of their income — and the actual cost of rent. It adjusts as incomes and rent prices change, which are outside of tenants’ control.

Research has shown that housing vouchers are highly successful for rehousing families with children, have been critical to cutting veteran homelessness in half since 2009, and are key to expanding supportive housing for people with disabilities and chronic conditions who need extra services and supports to maintain housing.

Some people need a broad array of supportive services to find and keep housing throughout their lives. These include services that help people navigate the housing market, find physical and mental health care and substance use services, and secure the income needed to afford housing. These services must be voluntary and individualized. But funding for them is disjointed and too low, making it difficult to implement and expand evidence-based housing solutions and replicate the success of the Department of Housing and Urban Development-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing program and other Housing First strategies that pair services with rental assistance.

We can scale up these best practices by:

Building toward universal federal rental assistance. The federal government should ultimately guarantee rental assistance for all eligible low-income people. In the meantime, federal policymakers can expand rental assistance for people with the lowest incomes, such as people with incomes at or below 30 percent of area median income. Expanding assistance based on income, instead of for certain subpopulations, is a more equitable and comprehensive approach for expanding federal rental assistance and is an important strategy for reducing homelessness.

States can move us closer to universally available help by expanding on the more than 100 state and local rental assistance programs that already exist, most of which help lower-income renters and people experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

- Maximizing state Medicaid coverage of services that support housing stability, including tenancy support, mental health, substance use, and home- and community-based services. In addition to covering a wide array of services, states should ensure that Medicaid payment rates reflect the full cost of delivering high-quality services so providers can hire qualified staff and pay them dignified wages that also can support retention and care continuity. Policymakers should also fully fund public housing agencies that run rental federal assistance programs and Continuums of Care that coordinate local or regional homelessness services, in order to support adequate staffing levels needed to implement best practices.

Other policies can also support ending homelessness, such as: raising wages for the lowest earners; improving public benefits such as Supplemental Security Income for older adults and people with disabilities or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; increasing tax credits for households with low incomes; enhancing tenant protections to address rising rent costs, landlord-imposed junk fees, discrimination, and evictions; preserving existing affordable housing; and building new units in communities with inadequate housing stock.

We know what works to help people afford and maintain housing — that is what communities and government at all levels should be focused on.