BEYOND THE NUMBERS

A Clear Policy Choice: Repeat Success by Expanding the EITC for Adults Without Children

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) provides a powerful wage boost. But for three decades, this bipartisan policy success has provided limited help to adults who work for low wages and who are not raising children in their homes. Policymakers expanded the EITC for these adults in the 2021 American Rescue Plan, boosting the incomes of more than 16 million people — more than double the number who benefited the year before the expansion. But the EITC expansion expired after 2021, leaving these adults with a paltry credit or no credit at all once again. Policymakers can repeat the Rescue Plan’s success by expanding the EITC as part of any tax package they consider this year.

People who do important jobs for low pay are integral to our communities. They deserve better than the flawed current EITC for adults without children, and policymakers can choose to fix it.

Under current law, for adults between the ages of 25 and 64 who are not raising children, the EITC phases in at a slow 7.65 cents per dollar of earnings up to $7,840 in earnings in 2023, and then quickly begins to phase out. This design suffers from three glaring flaws:

- The maximum 2023 credit is just $600 but relatively few filers even receive the max. A single filer who works full time at the federal minimum wage and earns $14,500 per year gets just $240.

- Childless adults who have modest earnings receive nothing due to the narrow income range of eligibility. No working adult without children making more than $17,640 today ($24,210 for married couples) receives a dime of EITC.

- Young adults aged 19 to 24, coming out of school and trying to get a toehold in the labor market, and those 65 and older, continuing to work to pay their bills, are ineligible for the EITC for adults without children.

Largely because the EITC for adults who aren’t caring for children is so paltry — or even zero for many — the federal tax code taxes more than 5 million adults aged 19 and older into, or deeper into, poverty each year. That’s because their EITC is too small to offset the payroll taxes they pay for Social Security and Medicare and any federal income tax liability they incur. These adults are disproportionately Black, Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) — groups who are overrepresented in low-paid work due to past and present hiring discrimination, inequities in educational and housing opportunities, and other sources of inequality.

The Rescue Plan temporarily expanded the EITC for workers without children for 2021, raising the incomes of more than 16 million adults, according to unpublished IRS data. This included about 9.4 million white, 2.9 million Latino, 2.6 million Black, 779,000 Asian, and 346,000 AIAN adults, we estimate, based on Census data.

The Rescue Plan addressed the EITC’s first two flaws by raising the maximum credit for workers without children in 2021 from about $500 to $1,500 and raising the income limit to qualify from roughly $16,000 to $21,000 (roughly $23,000 to $27,000 for married filers). It also addressed the credit’s third flaw, expanding the age range for eligible adults to include 3.8 million young adults aged 19-24 and 2.3 million people aged 65 and older for the first time, we estimate.

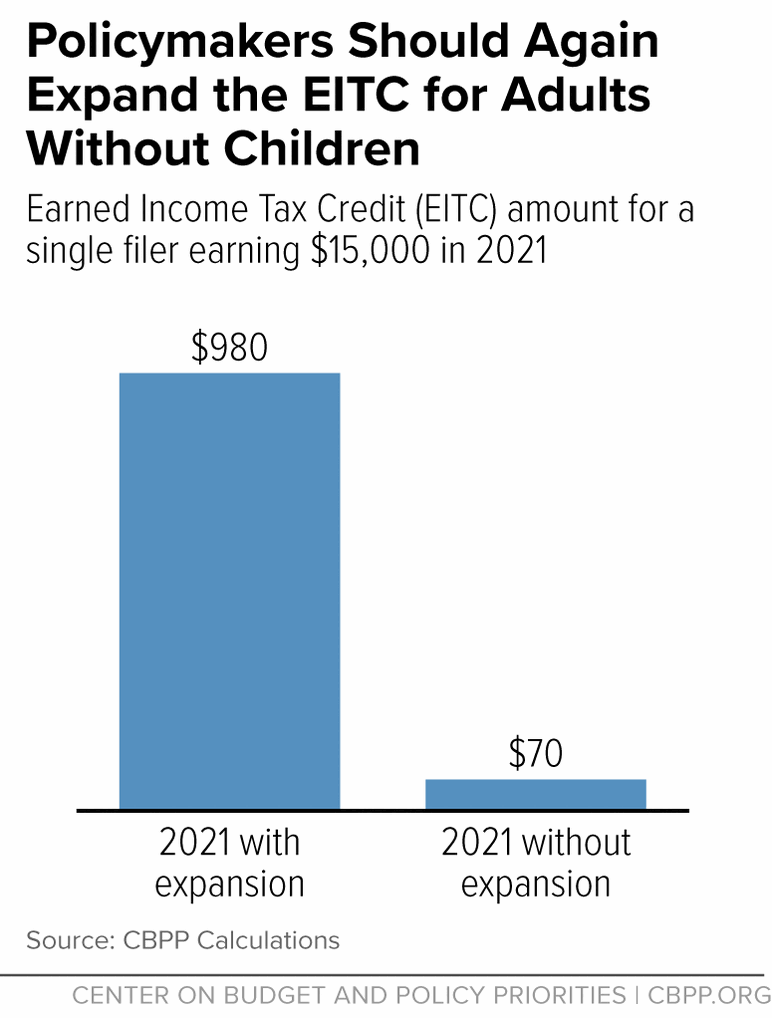

To see the difference this policy change made, picture a child care provider who worked 30 hours a week in 2021 earning an hourly wage of $10, or about $15,000 in annual earnings. Absent the Rescue Plan, her EITC would have been just $70. Instead, her EITC was $980 — a substantial difference she could use to help pay rent, buy groceries, or cover transportation costs to and from work. (See chart.)

The Rescue Plan expansion nearly eliminated the glaring policy failure that taxes millions of people into, or deeper into, poverty.

As they did in the Rescue Plan expansion, policymakers must recognize and address all of the current EITC’s flaws.

Consider two people working in a retail store: one a 22-year-old man who stocks shelves and covers the floor while another is a 68-year-old woman who checks out customers at the register. As in the chart above, both make $15,000 a year. In 2021, if policymakers had simply expanded the age range to include younger and older adults, each of these two people would have continued to receive a paltry $70 credit. It’s only because policymakers also addressed the other design flaws — the low maximum amount and income range — that each received $980 instead.

The EITC provides limited help or no help at all to the millions of adults — young, middle-aged, and older — who are not raising children and who do important jobs but get paid little. As policymakers consider tax legislation this year and beyond, they should choose to once again expand the EITC for this group.