Extend CARES Act Eviction Moratorium, Combine With Rental Assistance to Promote Housing Stability

End Notes

[1] Sharon Parrott et al., “More Relief Needed to Alleviate Hardship: Households Struggle to Afford Food, Pay Rent, Emerging Data Show,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 21, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/more-relief-needed-to-alleviate-hardship.

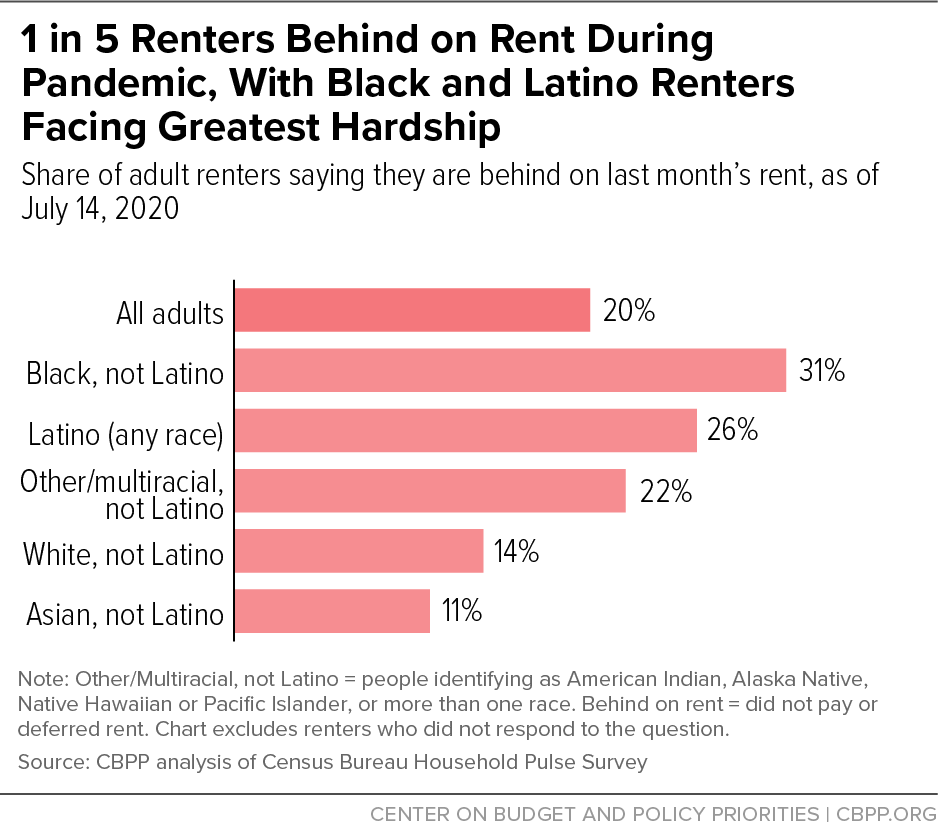

[2] Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey data, Housing Table 1b. Last Month’s Payment Status for Renter-Occupied Housing Units, by Select Characteristics: United States, for data collected July 9-14, 2020, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp11.html.

[3] Sarah Stein and Nisha Sutaria, “Housing Policy Impact: Federal Eviction Protection Coverage and the Need for Better Data,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, https://www.frbatlanta.org/community-development/publications/partners-update/2020/covid-19-publications/200616-housing-policy-impact-federal-eviction-protection-coverage-and-the-need-for-better-data.aspx.

[4] Debby Mayne, “Ten Biggest Expenses of the American Family,” PocketSense, October 31, 2018, https://pocketsense.com/ten-biggest-expenses-of-the-american-family-5646654.html.

[5] The legislation differentiates between mortgages for single-family properties, which have 1-4 units, and multifamily properties, which have 5 or more units, but tenants have the same protections regardless of the building’s size.

[6] Stein and Sutaria, op. cit; Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, “America’s Rental Housing 2020,” January 31, 2020, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2020.pdf.

[7] Federal Housing Finance Agency, Press Release, June 17, 2020, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Extends-Foreclosure-and-Eviction-Moratorium-6172020.aspx#.

[8] For more information on state eviction moratoriums, Eviction Lab has created a detailed scorecard for each state: https://evictionlab.org/covid-policy-scorecard/.

[9] See Eviction Lab’s eviction tracking at https://evictionlab.org/eviction-tracking/.

[10] Cary Spivak, “Predicted surge comes true: Eviction filing jump over 40% in Milwaukee County and state,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 15, 2020, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/investigations/reports/2020/06/15/evictions-milwaukee-and-wisconsin-jump-over-40/3177897001/.

[11] Micaela Watts, “9,000 eviction hearings stalled by coronavirus resume Monday. Advocates say it’s the beginning of a crisis,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, June 14, 2020, https://www.commercialappeal.com/story/news/2020/06/14/evictions-stalled-coronavirus-resume-monday-memphis/5328897002/.

[12] Eviction Lab, “Eviction Tracking,” updated July 11, 2020, https://evictionlab.org/eviction-tracking/.

[13] Jenny Schuetz, “Halting evictions during the coronavirus crisis isn’t as good as it sounds,” Brookings Institution, March 25, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/03/25/halting-evictions-during-the-coronavirus-crisis-isnt-as-good-as-it-sounds/.

[14] Matthew Desmond, “Unaffordable America: Poverty, housing, and eviction,” Institute for Research on Poverty at University of Wisconsin-Madison, March 2015, https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/fastfocus/pdfs/FF22-2015.pdf.

[15] Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey data, Housing Table 1b. Last Month’s Payment Status for Renter-Occupied Housing Units, by Select Characteristics: United States, for data collected July 9-14, 2020, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp11.html.

[16] “Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Prevalence in Homeless Shelters — Four U.S. Cities, March 27-April 15, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 1, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6917e1.htm?s_cid=mm6917e1_w.

[17] Carey L. Biron, “Closed bathrooms afflict U.S. homeless in coronavirus lockdown,” Reuters, May 26, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-usa-homelessness-f/closed-bathrooms-afflict-u-s-homeless-in-coronavirus-lockdown-idUSKBN2321FX.

[18] Marybeth Shinn et al., “Long-Term Associations of Homelessness with Children’s Well-Being,” American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 51, No. 6, February 2008; Linda C. Berti et al., “Comparison of Health Status of Children Using a School-Based Health Center for Comprehensive Care,” Journal of Pediatric Health Care, Vol. 15, September/October 2001.

[19] Berti et al., op. cit.

[20] Stanley K. Frencher et al., “A Comparative Analysis of Serious Injury and Illness among Homeless and Housed Low Income Residents of New York City,” Trauma, Vol. 69, No. 4, October 2010.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Jelena Obradovic et al., “Academic Achievement of Homeless and Highly Mobile Children in an Urban School District,” Development and Psychopathology, 2009.

[23] Natasha Menon, “A Comparative Analysis of Urban Eviction Prevention Policies in New York City, Philadelphia, and San Francisco,” University of Pennsylvania, April 27, 2020, https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1039&context=ppe_honors.

[24] Desmond, op. cit.

[25] Kathleen Ziol-Guest and Ariel Kalil, “Frequent Moves in Childhood Can Affect Later Earnings, Work, and Education,” MacArthur Foundation, March 2014, https://housingmatters.urban.org/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/How-Housing-Matters-Policy-Research-Brief-Frequent-Moves-in-Childhood-Can-Affect-Later-Earnings-Work-and-Education.pdf.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Order of Reversal (https://www.nhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020-CW-0531-Notice-Judgment-and-Disposition.pdf), Application (https://www.nhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/1st-Circuit-Writ-ADA.pdf), and Amicus Brief (https://www.nhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020.6.23-Amicus-BQ.pdf) litigation materials from Louisiana concerning a trial court’s denial of a woman’s request to hear an eviction case remotely due to a disability, which rendered her unable to attend an in-person hearing due to a higher risk of serious consequences as a result of possible COVID-19 infection. The justice of the peace court denied to order a remote hearing, and the tenant filed an application for review in the Louisiana Court of Appeals, granted in the order above. NHLP, “COVID-19 Litigation Resources,” July 8, 2020, https://www.nhlp.org/campaign/protecting-renter-and-homeowner-rights-during-our-national-health-crisis-2/.

[28] Congressional Budget Office, “Interim Economic Projections for 2020 and 2021,” May 19, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56351.

[29] Some states and cities have realized this and utilized existing state-funded rental or housing assistance programs or federal fiscal relief to provide limited rental and mortgage assistance, but the resources have gone quickly and left many people without any help. See: David Roeder, “Citing huge need, city officials start issuing $1,000 grants for housing costs,” Chicago Sun Times, April 7, 2020, https://chicago.suntimes.com/coronavirus/2020/4/7/21212348/chicago-rent-mortgage-relief-housing-assistance-grants; Liz Navratil, “Minneapolis receives more than 7,800 requests for rental assistance,” Star Tribune, April 27, 2020, https://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-receives-more-than-7-800-requests-for-rental-assistance/569991162/; Tony Gorman, “DSHA halts renters relief program after being swamped with applications,” Delaware Public Media, April 27, 2020, https://www.delawarepublic.org/post/dsha-halts-renters-relief-program-after-being-swamped-applications; Marisa Kendall, “Three days after launch $11 million Santa Clara County coronavirus relief fund runs out of money,” Mercury News, March 27, 2020, https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/03/27/three-days-after-launch-11-million-coronavirus-relief-fund-runs-out-of-money/.

[30] Center for Evidence-based Solutions to Homelessness, “Homelessness Prevention: A Review of the Literature,” January 2019, http://www.evidenceonhomelessness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Homelessness_Prevention_Literature_Synthesis.pdf.

[31] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “The 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress,” December 2016, https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2016-AHAR-Part-2.pdf.

[32] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics Summary,” U.S. Department of Labor, February 26, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.nr0.htm.

[33] This is the cost over five years. Representative Maxine Waters (D-CA) and Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) both introduced proposals (H.R. 7084 and S. 4164, respectively) to provide $10 billion for 200,000 new vouchers.

[34] Vouchers for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness may also be helpful for people transitioning from publicly funded institutional care settings — such as nursing homes — or from jail or prison and who were homeless prior to entering the facility or lack the resources needed to prevent becoming homeless upon returning to the community. See 24 CFR § 576.2.

[35] Will Fischer, Douglas Rice, and Alicia Mazzara, “Research Shows Rental Assistance Reduces Hardship and Provides Platform to Expand Opportunity for Low-Income Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 5, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/research-shows-rental-assistance-reduces-hardship-and-provides-platform-to-expand.

[36] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Three Out of Four Low-Income At-Risk Renters Do Not Receive Federal Rental Assistance,” updated August 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/three-out-of-four-low-income-at-risk-renters-do-not-receive-federal-rental-assistance.

[37] Among households with a voucher, 48 percent are headed by a person identifying as Black, non-Hispanic, 18 percent by a Hispanic person of any race, 3 percent by someone non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, and 1 percent by someone Native American, non-Hispanic. See Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Picture of Subsidized Households,” 2019, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/assthsg.html.

[38] Roughly 38 percent of Black, non-Hispanic low-income renter households in need of federal rental assistance receive it, compared to 25 percent of all low-income renter households in need. Regardless of race, funding limitations prevent most renters in need of assistance from getting help. CBPP analysis of HUD custom tabulations of the 2017 American Housing Survey; 2017 HUD administrative data; FY2018 McKinney-Vento Permanent Supportive Housing bed counts; 2017-2018 Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS grantee performance profiles; and the USDA FY2018 Multi-Family Fair Housing Occupancy Report.