Federal rental assistance programs support work by enabling low-income households to live in stable homes and freeing up income to meet the additional costs of working, such as transportation to jobs. Nearly 90 percent of the more than 4.6 million households that receive rental assistance through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) are elderly, disabled, working (or worked recently), or likely had access to work programs under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. The typical working household receiving federal rental assistance is a family with two school-age children and a parent who works at a job that does not pay enough to cover the market rent for a modest apartment. Only a small share of non-elderly, non-disabled adults receiving assistance are persistently unemployed. These individuals face significant barriers to work due to low levels of education, serious health problems, or because they are providing full-time care for a pre-school child or family member with a disability or serious illness. These households are also more likely to live in areas of higher poverty and unemployment.

Section 1: Large Majority of HUD Households Are Seniors, Have Disabilities, or Work

Section 2: Employment Is Common Among Working-Age, Non-Disabled Households, but Their Income Is Inadequate to Pay Rent

Section 3: HUD-Assisted Households That Aren’t Working Likely Have Significant Employment Barriers

Section 4: External Factors Affecting HUD-Assisted Households That Aren’t Working

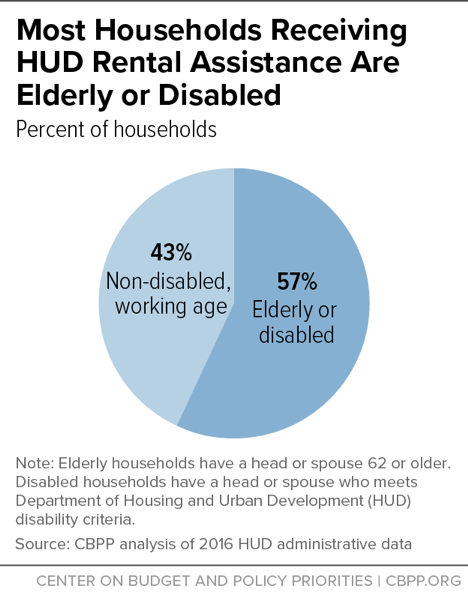

More than half — 57 percent — of the 4.6 million households receiving HUD rental assistance[1] have a head or spouse who is an elderly adult (defined by HUD as age 62 or older) or person with disabilities. [2] HUD considers these households to be elderly or disabled. Most HUD-designated elderly and disabled households do not work. Forty-three percent of assisted households would be considered potentially “work-able,” that is, the head or spouse is not elderly and not disabled.

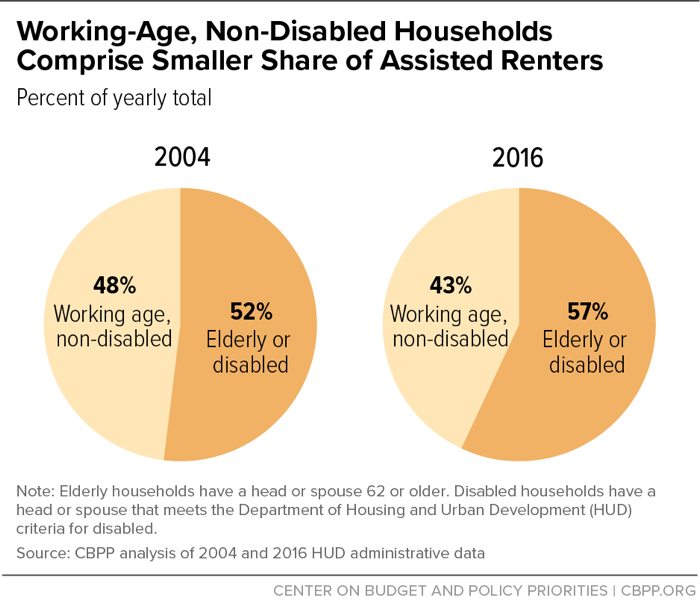

A shrinking share of HUD-assisted households are headed by working-age adults without disabilities. Working-age, non-disabled households represented 43 percent of all HUD-assisted households in 2016, down from nearly half of households in 2004. This is partly due to federal policymakers (and state and local housing agencies in some cases) primarily targeting homeless veterans and people with disabilities for newly available vouchers.[3]

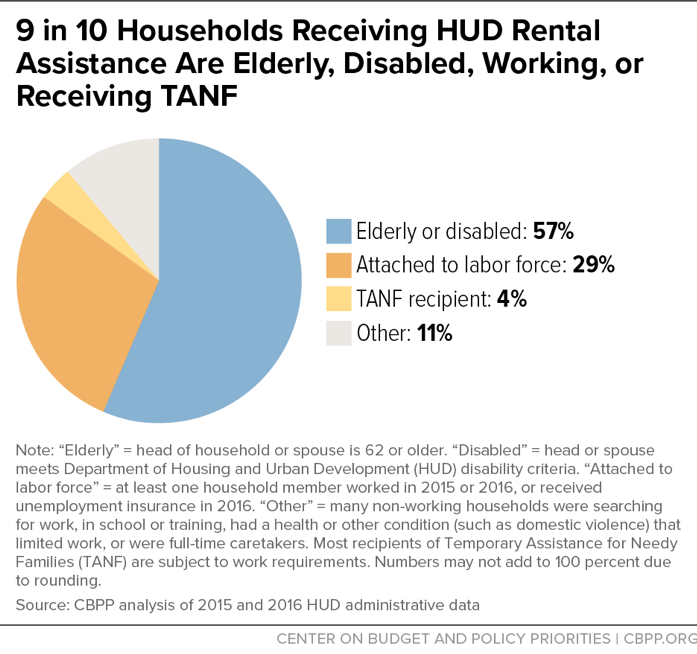

Of the roughly 4.6 million households receiving HUD rental assistance in 2016, 85 percent had a head or spouse that was elderly or disabled, or had at least one adult attached to the labor force.[4] Just 15 percent were not working, though some of those households likely were required to participate in work programs, such as job training or job search assistance, under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

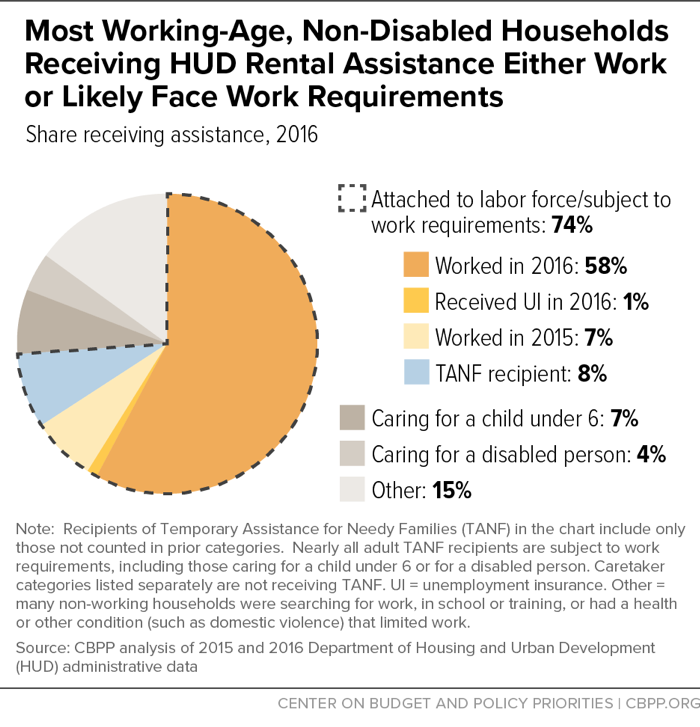

Two-thirds of working age, non-disabled HUD households are attached to the labor force, and an additional 8 percent likely were required to participate in work-related activities through TANF. Caretaking responsibilities likely prevent some households from working: in 2016, 7 percent of non-working households were caring for a child under 6 and 4 percent were caring for a family member with a disability. The adult in other non-working households may be searching for work, in school or training, or have severe or chronic health barriers to work, despite not being deemed disabled by HUD program administrators. (Only 6 percent of working-age, non-disabled HUD households that were not attached to the labor force or receiving TANF in 2016 had two or more adults.)

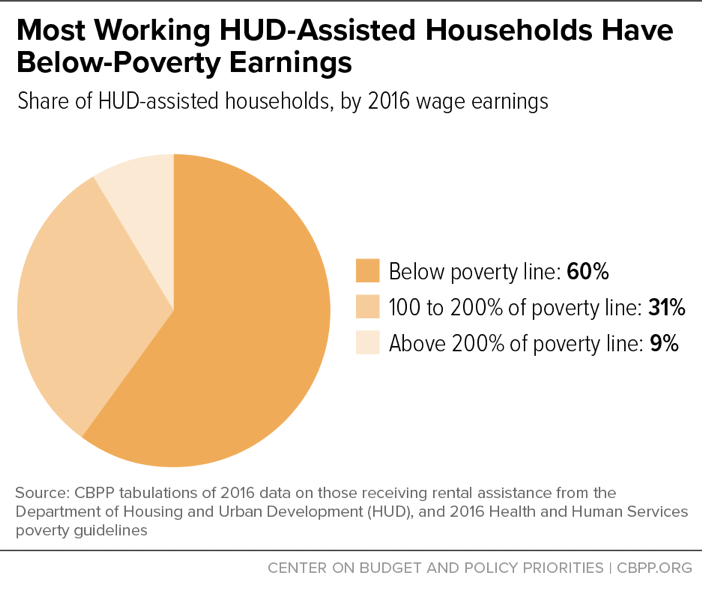

Fifty-six percent of working HUD households have earnings below the federal poverty line, which was $20,160 for a family of three in 2016.[5] Households with higher earnings remain eligible for rental assistance if their incomes are insufficient to pay market rents in the area.

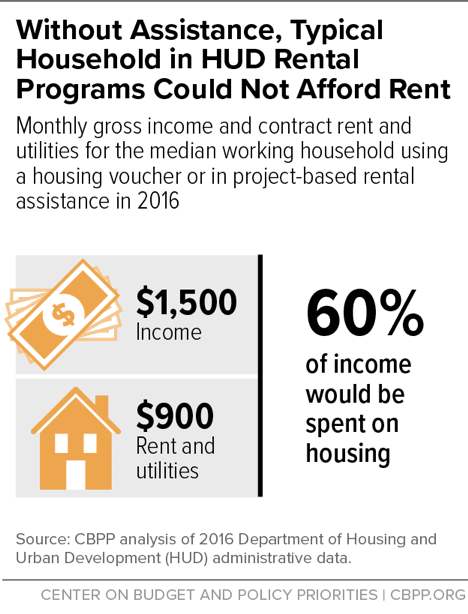

The typical working family receiving rental assistance is headed by a 38-year-old woman with two school-age children. She has an annual income[6] of roughly $18,200, the majority of which comes from working at a low-wage job. That means she can only afford to pay about $450 for rent and utilities and still have enough money available to get to work and cover other essential costs, based on HUD’s standard for affordability, which is set at 30 percent of a household’s income. But the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the United States is $963 per month,[7] which means that without rental assistance she cannot afford an apartment without paying over 30 percent of her monthly income. If she were to rent her current apartment without HUD assistance, she would pay 60 percent of her income for rent, leaving $600 to cover all her family’s remaining expenses for the month.

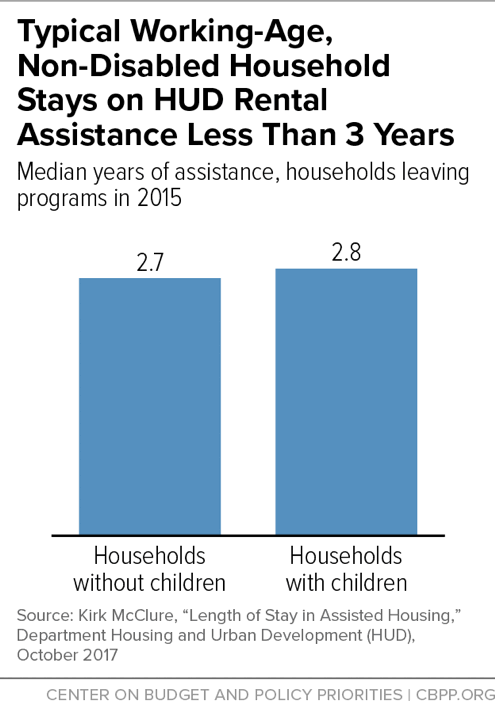

Despite low earnings, households that would reasonably be expected to work do not receive rental assistance for very long. The typical working-age, non-disabled household that left HUD rental programs in 2015 had received assistance for less than three years, compared to over three years for households headed by a person with disabilities and over six years for senior-headed households.[8]

HUD-assisted households that are not working, particularly those detached from the labor force for a long period, are more likely to face significant barriers to work, including chronic health problems, low levels of education, full-time caretaking responsibilities or domestic violence.

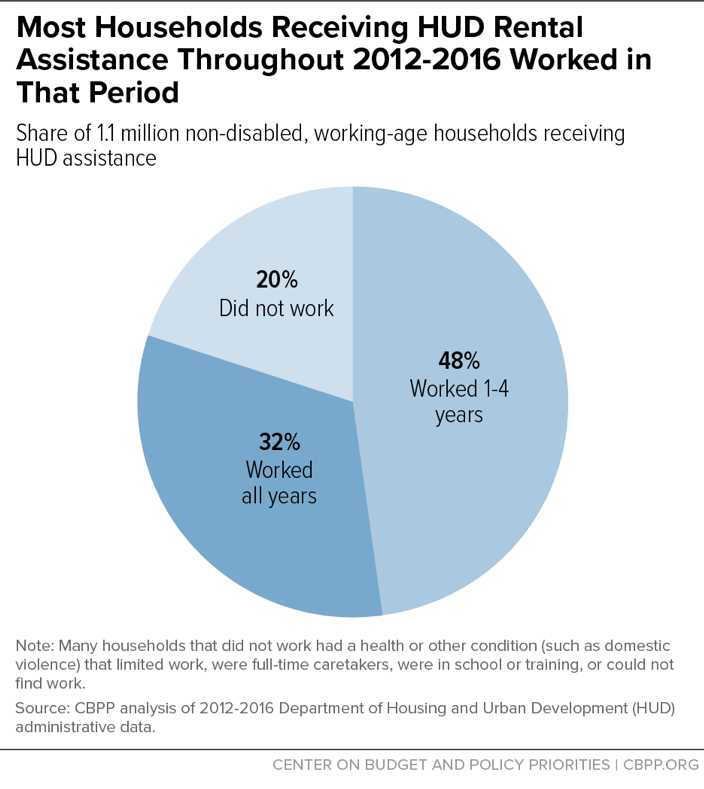

While the vast majority of working-age, non-disabled HUD-assisted households have a recent work history, most work in low-wage jobs, which often feature high turnover rates and few benefits like sick leave, contributing to unstable employment. Among households continuously receiving rental assistance between 2012 and 2016, 80 percent worked in at least one year out of the period. However, labor force attachment is tenuous for many of these households. About a third of households worked in each of the five years; about half worked in some years; and a fifth (227,000 households) did not work at all.

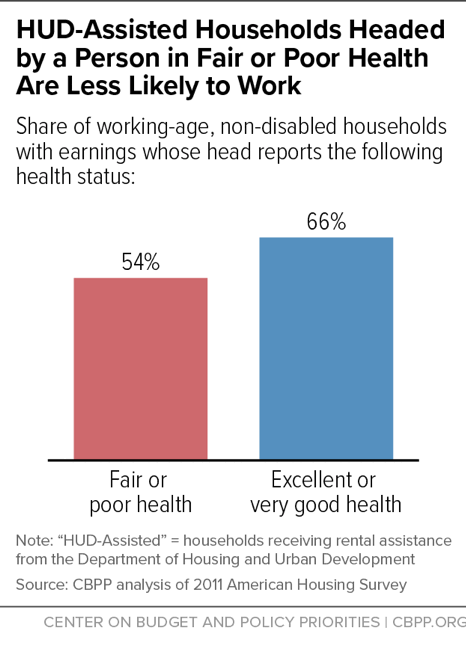

Non-working HUD households are more likely to struggle with health problems that make it difficult to find or sustain employment. Working-age, non-disabled HUD households whose heads report fair or poor health work at lower rates than those reporting very good or excellent health. Although these less healthy households have not met HUD’s eligibility criteria for a disability, which are very stringent, they can have serious health conditions that limit or prevent work. An MDRC survey of working-age, non-disabled public housing households at eight developments in seven cities found that 31 percent of households with no prior work history had a health condition that limited work, compared to 17 percent of households who were employed full-time. Additionally, 45 percent of working-age, non-disabled households with no employment history described their health as fair or poor, close to twice the rate of those working full-time.[9] Self-described health status, particularly a rating of fair or poor health, is associated with an increased risk of mortality, numerous studies show.[10]

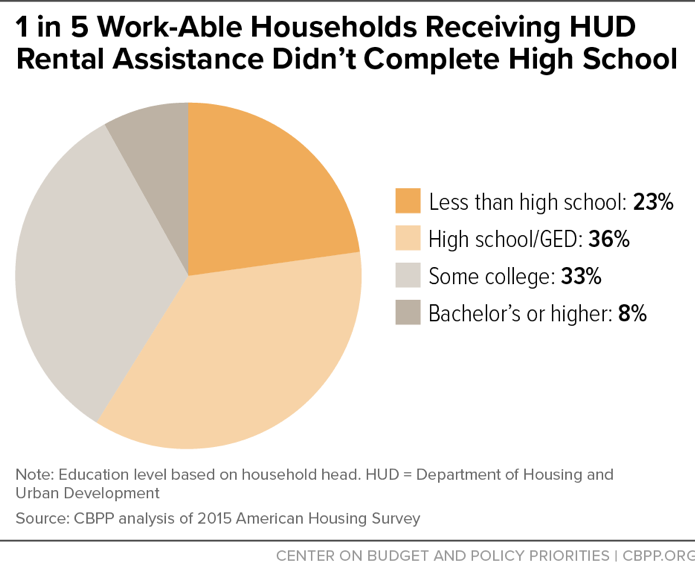

Many HUD households also have lower levels of education, which limits their job opportunities. Thirty-seven percent of working age, non-disabled household heads have a high school degree or equivalent and 22 percent did not finish high school. Those without a high school degree face particularly significant challenges in the labor market.[11] Half of working-age, non-disabled household heads with less than a high school education in public housing or the voucher program worked in 2015, compared to 72 percent of comparable household heads with a high school degree or GED.[12] The MDRC survey of working-age, non-disabled public housing residents also found that residents with lower levels of education were less likely to work, while those with higher levels of education were more likely to work. Among households with no prior work history, 70 percent had not completed high school or received a GED.[13]

HUD households report that not having enough education or training makes it difficult to find a job or find a better job. For example, 53 percent of working-age, non-disabled public housing residents in Boulder, Colorado and 57 percent of Housing Choice Voucher recipients in Charlotte, North Carolina cited lack of education or skills as a barrier to employment.[14]

Labor force attachment among HUD households varies by race and ethnicity. Our analysis considers a household attached to the labor force if any adult in the household had any wage earnings in 2016, received unemployment insurance in 2016, or had wage earnings in 2015 and did not work or receive unemployment insurance in 2016. (HUD does not collect data on hours worked or job search activities.) Most working-age, non-disabled HUD households are black or Hispanic/Latino, populations that typically face higher unemployment rates than white workers.[15] Despite this, roughly two-thirds of working age, non-disabled black and Hispanic/Latino households are attached to the labor force, compared to 63 percent of white, non-Hispanic households. Asian/Pacific Islander households have the highest rate of labor force attachment (83 percent), and Native American households have the lowest (58 percent), but relatively small numbers of either group receive rental assistance.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Household Characteristic |

% attached to the labor force |

# attached to the labor force |

|---|

| All non-elderly, non-disabled households |

66% |

2,010,100 |

| |

|

|

| Household head’s race/ethnicity |

|

|

| Asian/Pacific Islander alone |

83% |

39,800 |

| Black alone |

67% |

1,098,700 |

| Hispanic, any race |

66% |

416,200 |

| Native American alone |

58% |

14,300 |

| White alone |

63% |

409,100 |

| Family structure |

|

|

| Households with children |

67% |

1,463,600 |

| Single adult with children |

62% |

1,024,800 |

| Two or more adults with children |

78% |

438,800 |

| Households without children |

64% |

546,500 |

| Age of children |

|

|

| At least one child under 6 |

64% |

723,000 |

| All children are school-age |

69% |

740,600 |

Among working age, non-disabled households, families with children are more likely to be attached to the labor force than households without children, particularly if there are two adults in the household. Close to 80 percent of households with two or more adults raising children have at least one adult attached to the labor force, compared to 62 percent of single parents, indicating that access to child care significantly affects a household’s ability to stay in the labor force.

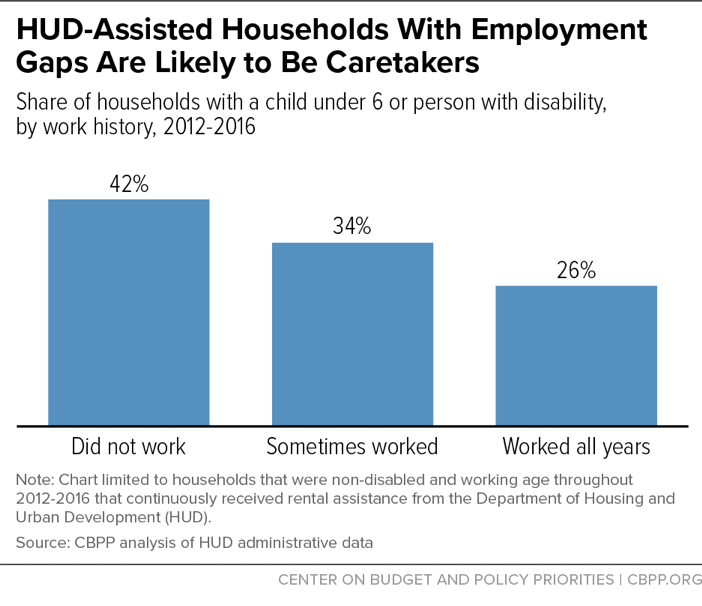

Full-time caretaking responsibilities can prevent otherwise work-capable households from getting and keeping a job. Low-income households receiving rental assistance do not necessarily have access to affordable care for children or for other household members with disabilities. Child care assistance programs serve less than 1 in 6 eligible children[16] because of a lack of funding and very little help is available to relieve caretaking responsibilities for those caring for adult family members with disabilities. Without access to affordable, safe care for children or adult family members with disabilities, work can be impossible. This can lead to gaps in employment or long periods of unemployment. Over 40 percent of working-age, non-disabled HUD households that did not work between 2012 and 2016 lived with a person with disabilities or a child under 6. A third of households with intermittent work histories between 2012 and 2016 had similar caretaking responsibilities, compared to just a quarter of households who worked the entire period.

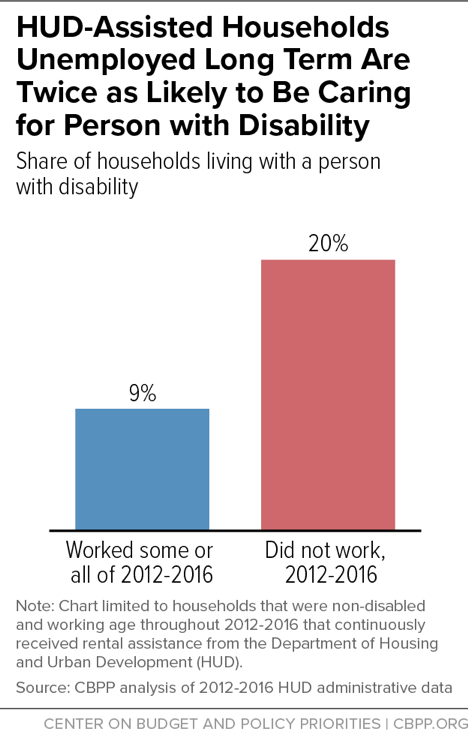

Caring for a person with a disability makes it particularly difficult for many HUD households to maintain an attachment to the workforce. This type of care may require significant amounts of time and energy, and can involve tasks that are physically, emotionally, or financially demanding. These demands are especially tough for low-income families, as low-wage workers are less likely to have jobs with flexible schedules, sick days, and paid family and medical leave, and more likely to work irregular schedules. Many parents of children with disabilities reduce their hours, make different job choices, or leave the workforce altogether.[17] Households with children or adults with a disability are more likely to not have earnings over a longer period. Households that were not working between 2012 and 2016 were twice as likely to be caring for a family member with a disability as those who worked for some or all of the period.

External factors, like local unemployment or neighborhood poverty, also affect HUD households’ ability to find and sustain employment.

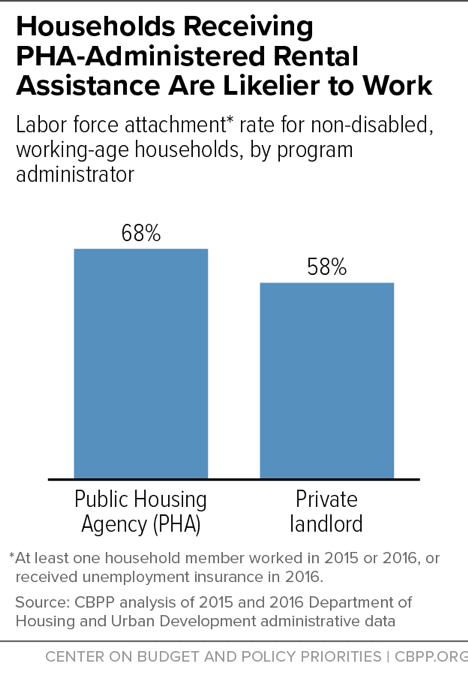

Nearly all working-age, non-disabled HUD households receive help from one of three major programs: Housing Choice Vouchers or Public Housing, which are administered by nearly 3,800 state and local public housing agencies, or Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA), which contracts with private landlords. Working-age, non-disabled households living in privately owned PBRA properties are less likely to work than their counterparts living in public housing or using a voucher administered by a public housing agency.

It is not clear why work is more prevalent among potentially work-able households in the programs that public housing agencies administer. One possible explanation is different levels of caretaking responsibilities. Among those potentially work-able, non-working PBRA households are twice as likely to have caretaking responsibilities that may prevent work as otherwise similar households in the public housing and housing voucher programs. Nineteen percent of non-working households in privately owned housing were caring for a child under 6 or a disabled family member, compared to just 9 percent of non-working households in housing administered by a public housing agency. Given that subsidized child care programs only have enough funding to serve a small share of eligible children and very little help is available to those caring for family members with disabilities, adults with these responsibilities can find it very difficult to work.

National and local unemployment and labor market conditions also impact HUD households seeking work. The share of working-age, non-disabled HUD households with an adult attached to the labor force has risen as the economy has recovered from the Great Recession. In 2016, 66 percent of working age, non-disabled HUD households were attached to the labor market, compared to 62 percent in 2010. While the national unemployment rate has improved, some HUD-assisted families live in communities with higher unemployment rates, affecting their job prospects. Households that did not have any working members in the last five years lived in counties with an average unemployment rate of 5.9 percent in 2016, 20 percent higher than the national unemployment rate of 4.9 percent.

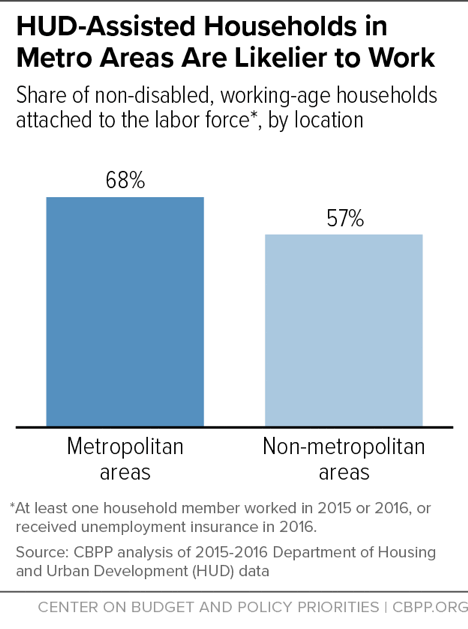

Differences in labor force attachment are especially pronounced among households living outside metropolitan areas, which typically have higher unemployment rates.[18] Fifty-seven percent of working-age, non-disabled HUD households in non-metropolitan areas were attached to the labor force in 2016, compared to 68 percent of their metropolitan counterparts. Non-metropolitan HUD households that did not have any working members in the last five years lived in counties with an average unemployment rate of 9.0 percent in 2016.

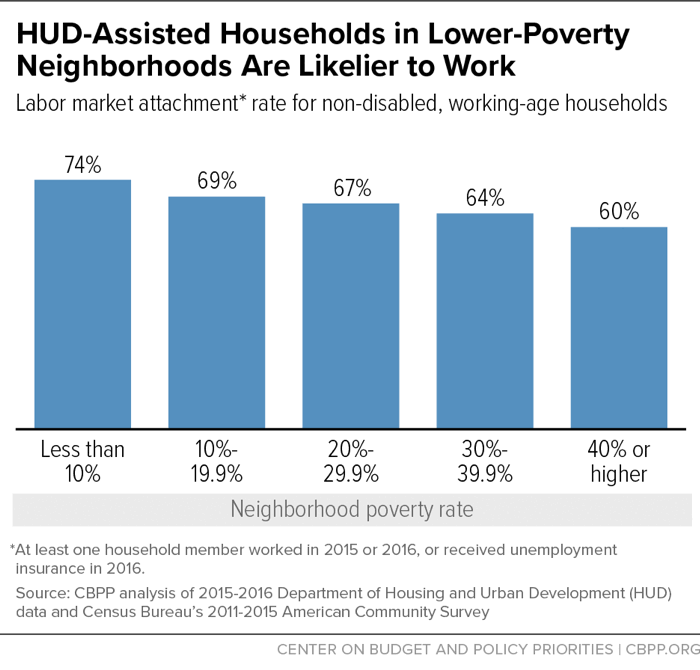

Of course, unemployment rates can vary widely within counties, and local factors, such as neighborhood quality, can also affect employment. Low-income families in low-opportunity neighborhoods may have a harder time securing employment, while families in high-opportunity neighborhoods may have better access to employment than the county-wide unemployment rate suggests. Nearly three-quarters of HUD-assisted households in low-poverty neighborhoods (where less than 10 percent of residents are poor) were attached to the labor force. Assisted households in extreme-poverty neighborhoods (where at least 40 percent of residents are poor) were least likely to work, with 60 percent of households attached to the labor force.

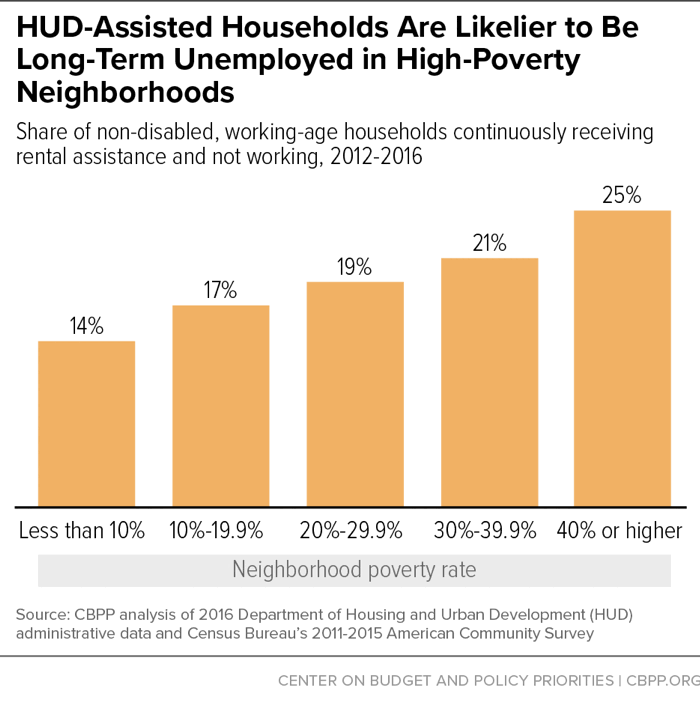

Living in an extremely poor neighborhood is also associated with higher rates of long-term unemployment. A quarter of working-age, non-disabled HUD households living in extreme-poverty neighborhoods did not work at all between 2012 and 2016, compared to just 14 percent of their counterparts in low-poverty neighborhoods.