- Home

- Medicaid Works For Women — But Proposed ...

Medicaid Works for Women — But Proposed Cuts Would Have Harsh, Disproportionate Impact

These cuts would have devastating consequences for the nearly 40 million women who rely on Medicaid.Republican leaders in Congress and the White House have proposed to deeply cut Medicaid by effectively eliminating the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion, and breaking the federal government’s decades-long guarantee to pay a set share of states’ Medicaid costs. These cuts would have devastating consequences for millions of Americans, including the nearly 40 million women who rely on Medicaid. Women would bear a disproportionate share of the burden because they make up a majority (53 percent) of Medicaid beneficiaries, are the primary utilizers of family planning and maternity care benefits, and are much more likely to use Medicaid’s long-term services and supports as they age. The Appendix tables at the end of this report provide state-specific data on Medicaid’s significant role in women’s health.

Medicaid Changes Have Expanded Women’s Access to Care

Originally, most adult women weren’t eligible for Medicaid: eligibility was limited almost exclusively to children, cash assistance recipients, seniors, and people with disabilities. Eligibility expansions in the 1980s and 1990s enabled many more low-income children, parents, and pregnant women in working families to qualify. Even with these changes, before the ACA, many low-income women were left out because they weren’t in a population category eligible for the program.[1]

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion changed that. In the 32 states that have expanded, women with incomes at or below 138 percent of the poverty line ($16,643 for a single person or $28,180 for a family of three in 2017) can enroll.

The Medicaid expansion gave women not raising children access to coverage and offered continuous coverage to new mothers who had qualified for Medicaid while pregnant but whose incomes were not low enough to qualify as a parent.[2] States that have yet to expand Medicaid have largely maintained Medicaid’s narrow eligibility criteria, preventing many low-income women from enrolling in Medicaid until they become pregnant and ending their eligibility 60 days after the birth of their child.[3]

Medicaid Provides Essential Health Services to Women of All Ages

Medicaid allows women to obtain the health care they need throughout their lives. Women have unique health care needs — they are the primary users of maternity care, family planning, and long-term care services — and nearly half of all women have an ongoing condition requiring regular monitoring, care, or medication.[4] Moreover, women use many other health benefits differently from men, such as mental health and substance use disorder treatment.

Women of reproductive age rely especially on Medicaid’s family planning and maternity care services. Medicaid covered 12.9 million women ages 15-44 in 2015 — 20 percent of all women in this age group and 48 percent of women in this age group with incomes below the poverty line.[5] Medicaid is also an essential support for women of color ages 15-44: 31 percent of African American women and 27 percent of Hispanic women in this age group are enrolled in Medicaid.[6]

Family Planning

Nearly all women use some form of family planning during their reproductive years, and Medicaid finances 75 percent of all publicly funded family planning services.[7] Family planning services are essential for women’s health: almost half of all pregnancies are unintended, and unintended pregnancies are associated with negative health and economic consequences for families as well as increased spending for states and the federal government.[8]

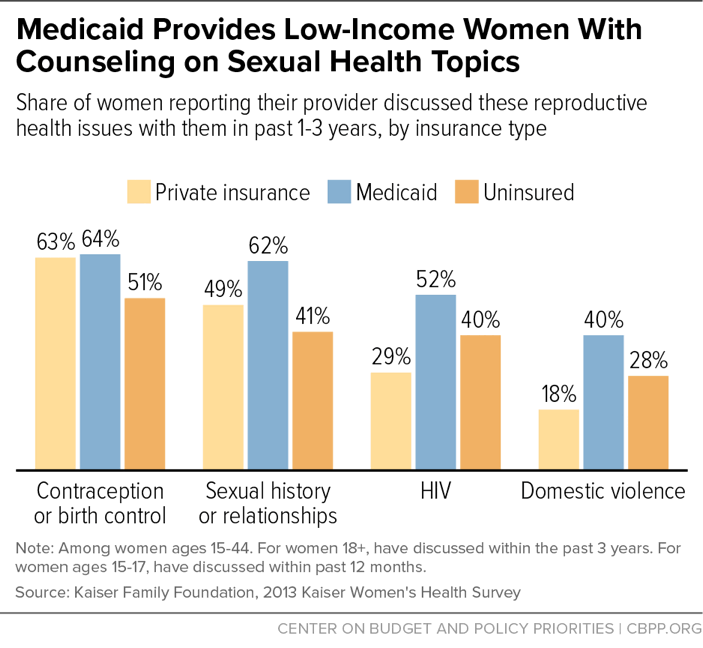

States must offer family planning services for women enrolled in Medicaid. The federal government funds 90 percent of the cost of these services — significantly higher than the 64 percent average federal match for most other Medicaid services. States have considerable flexibility deciding which family planning services to cover, but they generally cover contraceptive services and supplies, Pap smears, sexually transmitted disease testing, and counseling. These services are effective: in 2013, women with Medicaid coverage were more likely than women with private insurance to report they had spoken with a provider about sexual history, HIV, and intimate partner violence.[9] (See Figure 1.)

Medicaid’s family planning services have no cost-sharing charges, and women have “freedom of choice” of family planning providers. This means they can receive family planning services and supplies from any willing and qualified Medicaid provider.[10]

Texas Maternal Mortality Nearly Doubled After Family Planning Cuts

In 2011, the Texas legislature directed the state to prohibit organizations providing abortion from participating in the state’s Medicaid family planning waiver, even though Medicaid doesn’t cover abortion except in cases of rape or incest or danger to the woman’s life. In 2012, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services informed Texas that this prohibition deprived women of freedom of choice guaranteed by Medicaid law. Texas chose to end its federal family planning waiver rather than reverse the ban on providers that perform abortions. Although the state continues to provide limited funds for its family planning program, the number of family planning organizations receiving funds plummeted from 76 to 41 in two years,a and the use of long-acting, reversible contraceptives among Texas’ Medicaid beneficiaries declined more than one-third between 2011 and 2014.b

Also, an analysis of maternal mortality in Texas showed a near doubling in the reported rate of maternal deaths from 2011 to 2012. While the study’s authors didn’t examine the causes of increased maternal mortality (which the World Health Organization defines as death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days after pregnancy termination for causes related to the pregnancy), they cited access to women’s health services as a possible factor.c

a Usha Ranji, Yali Bair, and Alina Salganicoff, “Medicaid and Family Planning: Background and Implications of the ACA,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2016, http://kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-family-planning-the-aca-medicaid-expansion-and-family-planning/.

b Amanda J. Stevenson et al., “Effect of Removal of Planned Parenthood from the Texas Women’s Health Program,” The New England Journal of Medicine, February 2016.

c Marian MacDorman et al., “Recent Increases in the U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate: Disentangling Trends From Measurement Issues,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, September 2016, http://d279m997dpfwgl.cloudfront.net/wp/2016/08/MacDormanM.USMatMort.OBGYN_.2016.online.pdf

Over 20 years ago, states began using Medicaid waivers (technically known as section 1115 demonstration authority) to expand access to family planning services to women who would otherwise not qualify for Medicaid. These waivers provide family planning-related coverage to women with incomes above the state’s Medicaid limit, including those who lost Medicaid eligibility after having a baby. Before the ACA, 28 states used these waivers to provide family planning services to women.[11] More than half of states have used this authority to establish permanent family planning programs for people who would not otherwise qualify for Medicaid. Recognizing the success of these programs, the ACA allows states to permanently adopt their family planning programs as a state option without a waiver.[12]

Maternity Care

Medicaid provides health care for nearly half of all pregnant women, supporting them through their pregnancies and ensuring that their babies have a healthy start.[13] Medicaid has historically required states to cover pregnant women at much higher eligibility levels than other adults. All states must cover pregnant women up to 133 percent of poverty, and 34 states cover pregnant women with family incomes above 200 percent of poverty as of January 2017. Eligibility at these higher income thresholds extends through pregnancy and the 60 days after childbirth.[14]

The Medicaid expansion, by enabling states to bring other adults up to 138 percent of poverty without a federal waiver, has allowed many women to maintain continuous access to primary care and family planning services before and after pregnancy, and to avoid unintended pregnancy. When women have health coverage before becoming pregnant as well as between pregnancies, they are healthier during pregnancy and their babies are more likely to be healthy at birth, research shows. Between the birth of one child and the conception of another, health coverage gives women access to care that can improve the outcomes of subsequent pregnancies. This can include treatment for diabetes and hypertension; clinical interventions focused on combating family violence, depression, and stress; and other forms of parental support.[15]

States’ coverage of pre- and post-natal services varies significantly. Most states cover prenatal vitamins, ultrasounds, and prenatal testing such as amniocentesis, as well as substance use disorder treatment services for pregnant and postpartum women. Some states also offer education services to support childbirth, infant care, and parenting and to help women initiate and maintain breastfeeding, including breast pumps and lactation counseling.[16]

Infants born to women on Medicaid are automatically enrolled in the program until their first birthday.[17] This immediate and uninterrupted coverage is essential: research shows that people who had Medicaid during early childhood have better long-term health and achievement in adulthood than those who were uninsured.[18]

Medicaid can also play an important role in identifying children whose mothers experience depression and connecting mothers and children to the help they need. Guidance that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released in 2016 cites evidence showing that between 5 and 25 percent of all pregnant, postpartum, and parenting women have some type of depression; for mothers with low incomes, rates of depressive symptoms are between 40 and 60 percent. More than half of infants living in poverty are being raised by mothers with some form of depression.[19]

The guidance clarifies that states can include screening mothers for maternal depression as part of well-child visits even if the mother isn’t enrolled in Medicaid, because of evidence that maternal depression can place children at risk of adverse health consequences.[20]

Long-Term Care

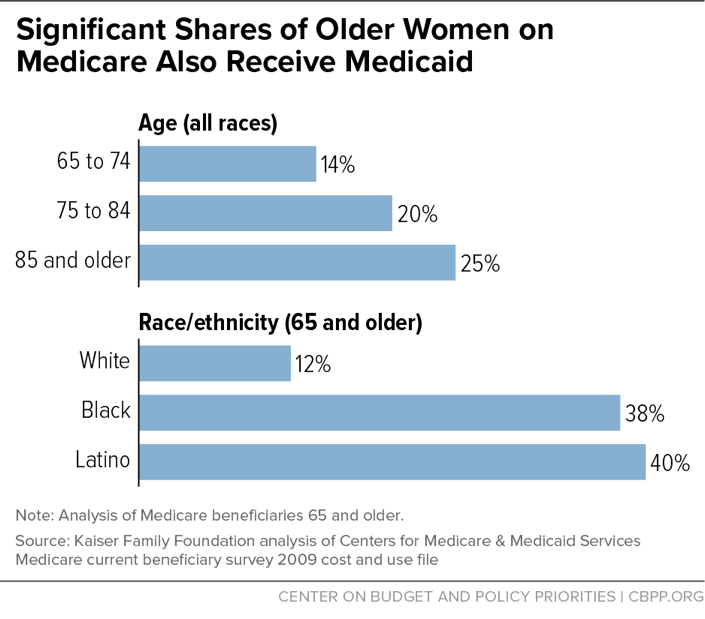

Medicaid helps women as they age, even when they become eligible for Medicare. Women live longer than men and are significantly more likely to need long-term care services through Medicaid. Sixty-nine percent of the 9 million dually eligible beneficiaries — people covered by both Medicare and Medicaid — are women. “Duals” are typically over 65 years of age or younger low-income individuals with disabilities who have significant health care needs. Medicaid plays an especially critical role for older women of color, covering nearly 40 percent of Latina and African American women over 65 who are also enrolled in Medicare.[21] (See Figure 2.)

Medicaid pays for half of the nation’s long-term services and supports,[22] and women make up seven in ten nursing home residents and over two-thirds of people receiving home and community based care.[23] Medicaid offers these services and supports in institutional settings like nursing homes as well as care in people’s homes, usually referred to as home- and community-based services (HCBS). HCBS include case management, home health aides, personal attendant services to help with daily living activities such as bathing and dressing, and adult day health.

Enormous progress has been made over the decades to increase access to care in home- and community-based settings, which are less expensive and where many seniors and people with disabilities prefer to live. In 2013, for the first time in the program’s history, Medicaid spent more on home- and community-based care than on institutional care.[24]

Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, coupled with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, have dramatically improved access to treatment for people with substance use disorders. Improved access is essential in addressing these disorders, which have received greater attention due to the opioid epidemic.

Prescription painkiller overdoses have increased precipitously in recent years and are a growing problem among women: more than five times as many women died from opioid overdoses in 2010 as in 1999 (6,631 versus 1,287). About 42 women die every day from substance use overdoses, including opioid overdoses. More than 200,000 women visited the emergency department for opioid-related conditions, or statistically one every three minutes.a

Women are more likely than men to report chronic pain and to be prescribed prescription painkillers; they also are given higher doses and use them for longer periods of time than men.b

Hundreds of thousands of people with substance use disorders have gained Medicaid coverage through the Medicaid expansion. This has had dramatic results. In states that expanded Medicaid, the share of people with substance use or mental health disorders who were hospitalized but uninsured fell from about 20 percent in 2013 to 5 percent by mid-2015.

a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Prescription Painkiller Epidemic Among Women,” https://www.cdc.gov/media/dpk/prescription-drug-overdose/prescription-painkiller-epidemic/index.html.

b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Prescription Painkiller Overdoses,” https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/prescriptionpainkilleroverdoses/index.html.

Medicaid Cuts Would Disproportionately Harm Women

The House Republican bill to repeal the ACA, the American Health Care Act (which passed the House on May 4), would radically restructure and deeply cut Medicaid, reducing enrollment by 14 million people by 2026. While the cuts would jeopardize care for all Medicaid beneficiaries, they would disproportionately affect women due to the higher proportion of women who rely on Medicaid and the specific services at risk of cuts.

The bill would cut $839 billion in federal spending from Medicaid over ten years by effectively eliminating the Medicaid expansion and permanently capping annual funding for states, regardless of the cost of services for their Medicaid beneficiaries.[25]

The legislation also specifically targets access to women’s health care services by barring states from reimbursing Planned Parenthood for its preventive health and family planning services for women and men enrolled in Medicaid. This would cause thousands of low-income women to lose access to care and raise state and federal Medicaid costs related to unplanned pregnancies. Fifteen percent of women on Medicaid who rely on Planned Parenthood for family planning services would lose access to those services, the Congressional Budget Office estimates.[26]

The bill also permits states to impose work requirements on Medicaid beneficiaries, which would penalize those least able to get and hold a job while keeping others from improving their health and participating in the workforce. Almost two-thirds of the 11 million beneficiaries who risk losing coverage from a work requirement are women.[27] Many of these are women with a disability or chronic health condition or who are caring for a family member. Many others have low-wage jobs that don’t offer health coverage.

The Republican bill isn’t the only threat to women’s health coverage. Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price, and CMS Administrator Seema Verma recently notified governors that the Trump Administration will give states greater flexibility to limit access to Medicaid enrollment and access to care.[28] CMS could allow states to waive many legal requirements and consumer protections that could disproportionately affect women and their access to coverage, including family planning services. These waivers would be a sharp departure from the family planning waivers discussed above, which enabled states to expand access to coverage.

Several states are considering seeking waivers to impose premiums and cost-sharing as a condition of Medicaid eligibility for people in poverty, which would limit access to care for many women.[29] States are also considering drug-testing Medicaid beneficiaries, setting time limits on Medicaid benefits, and requiring people to work or search for work in order to maintain their benefits. These proposals fail to advance Medicaid’s core objective of delivering health care to vulnerable populations who can’t otherwise afford it, as federal law requires of Medicaid waivers, and they would significantly restrict access to care for millions of women who rely on Medicaid as an essential support.

House Bill Would Also Harm Women with Private Insurance

The House bill also includes several provisions that are especially harmful to women with private insurance. For example, it would allow states to opt out of the ACA’s Essential Health Benefits (EHB) standard, leaving many women without affordable access — or any access — to maternity coverage. (Before the ACA, nearly two-thirds of people in the individual market had plans that lacked maternity coverage.a) The bill also would give states the option of allowing insurers to base premiums on people’s health status and medical history; insurers could charge far higher premiums to people who are pregnant, have had a c-section, take fertility drugs, were treated for injuries resulting from domestic violence, or have experienced irregular monthly periods.b

Moreover, allowing states to weaken or eliminate the EHB standard could effectively eliminate protections against high out-of-pocket costs for people with employer coverage. Women could once again face annual and lifetime caps on the amount their employer plans will pay out in benefits for particular services such as maternity care, or they might find their plans no longer cap the amount enrollees must pay each year for certain covered items and services.c

a Sarah Lueck, “If ‘Essential Health Benefits’ Standards Are Repealed, Health Plans Would Cover Little,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 23, 2017.

b National Partnership for Women and Families, “Why the Affordable Care Act Matters for Women: Summary of Key Provisions,” September 2015.

c Matthew Fiedler, “Allowing states to define “essential health benefits” could weaken ACA protections against catastrophic costs for people with employer coverage nationwide,” Brookings Institution, May 2017; Gary Claxton et al., “Pre-existing Conditions and Medical Underwriting in the Individual Insurance Market Prior to the ACA,” Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2016.

| TABLE 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Women and Girls Below the Poverty Line | ||

| State | Women and girls in poverty | Share of all women and girls in poverty |

| United States | 25,553,670 | 16.0% |

| Alabama | 494,820 | 20.2% |

| Alaska | 38,590 | 11.2% |

| Arizona | 627,260 | 18.5% |

| Arkansas | 301,940 | 20.4% |

| California | 3,186,480 | 16.4% |

| Colorado | 330,000 | 12.3% |

| Connecticut | 203,210 | 11.4% |

| Delaware | 64,490 | 13.5% |

| District of Columbia | 61,620 | 18.4% |

| Florida | 1,721,750 | 16.8% |

| Georgia | 960,060 | 18.7% |

| Hawaii | 77,380 | 11.1% |

| Idaho | 131,350 | 16.1% |

| Illinois | 948,920 | 14.8% |

| Indiana | 529,430 | 16.2% |

| Iowa | 204,320 | 13.4% |

| Kansas | 198,710 | 13.9% |

| Kentucky | 443,290 | 20.2% |

| Louisiana | 512,190 | 21.8% |

| Maine | 94,660 | 14.3% |

| Maryland | 330,940 | 10.9% |

| Massachusetts | 424,880 | 12.6% |

| Michigan | 844,630 | 17.1% |

| Minnesota | 298,900 | 11.1% |

| Mississippi | 361,100 | 23.9% |

| Missouri | 492,310 | 16.3% |

| Montana | 77,810 | 15.5% |

| Nebraska | 129,960 | 14.0% |

| Nevada | 223,690 | 15.6% |

| New Hampshire | 60,260 | 9.2% |

| New Jersey | 529,350 | 11.7% |

| New Mexico | 218,390 | 21.1% |

| New York | 1,663,960 | 16.7% |

| North Carolina | 898,200 | 17.8% |

| North Dakota | 43,500 | 12.2% |

| Ohio | 933,270 | 16.1% |

| Oklahoma | 338,690 | 17.6% |

| Oregon | 328,570 | 16.4% |

| Pennsylvania | 910,140 | 14.3% |

| Rhode Island | 78,900 | 15.1% |

| South Carolina | 445,210 | 18.1% |

| South Dakota | 63,660 | 15.4% |

| Tennessee | 594,620 | 17.9% |

| Texas | 2,354,740 | 17.3% |

| Utah | 178,950 | 12.2% |

| Vermont | 34,000 | 11.1% |

| Virginia | 513,610 | 12.3% |

| Washington | 462,810 | 13.1% |

| West Virginia | 179,800 | 19.7% |

| Wisconsin | 372,470 | 13.1% |

| Wyoming | 35,890 | 12.6% |

Source: American Community Survey, 2015

| TABLE 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| More Than 40 Million Women and Girls Are Enrolled in Medicaid | |||

| State | Female Medicaid Enrollees | Female Medicaid Enrollees as Share of Medicaid Population | Females as Share of Total Population |

| United States | 40,412,400 | 53.9% | 50.8% |

| Alabama | 491,300 | 55.0% | 51.6% |

| Alaska | 90,400 | 51.1% | 47.3% |

| Arizona | 920,000 | 52.9% | 50.4% |

| Arkansas | 507,400 | 53.5% | 51.0% |

| California | 6,584,400 | 53.1% | 50.4% |

| Colorado | 735,100 | 53.0% | 49.7% |

| Connecticut | 413,000 | 54.3% | 51.2% |

| Delaware | 133,200 | 55.1% | 51.9% |

| District of Columbia | 150,000 | 56.6% | 52.3% |

| Florida | 2,348,900 | 54.2% | 51.2% |

| Georgia | 968,300 | 55.2% | 51.3% |

| Hawaii | 181,100 | 52.3% | 49.6% |

| Idaho | 156,900 | 52.3% | 50.0% |

| Illinois | 1,679,700 | 54.8% | 51.0% |

| Indiana | 824,000 | 54.6% | 50.8% |

| Iowa | 339,700 | 54.6% | 50.4% |

| Kansas | 209,300 | 51.2% | 50.2% |

| Kentucky | 666,000 | 54.1% | 50.8% |

| Louisiana | 766,400 | 54.1% | 51.0% |

| Maine | 143,900 | 53.4% | 50.9% |

| Maryland | 704,000 | 54.9% | 51.7% |

| Massachusetts | 890,300 | 53.8% | 51.4% |

| Michigan | 1,229,200 | 52.8% | 50.9% |

| Minnesota | 554,600 | 52.8% | 50.3% |

| Mississippi | 377,600 | 55.2% | 51.6% |

| Missouri | 537,300 | 55.0% | 51.0% |

| Montana | 129,200 | 52.7% | 49.7% |

| Nebraska | 137,400 | 56.4% | 50.3% |

| Nevada | 330,300 | 53.0% | 50.0% |

| New Hampshire | 98,600 | 51.5% | 50.4% |

| New Jersey | 972,000 | 54.1% | 51.1% |

| New Mexico | 418,300 | 54.0% | 50.3% |

| New York | 3,470,600 | 54.1% | 51.4% |

| North Carolina | 1,128,100 | 54.1% | 51.3% |

| North Dakota | 51,600 | 54.5% | 48.7% |

| Ohio | 1,610,100 | 55.3% | 51.0% |

| Oklahoma | 426,900 | 53.1% | 50.5% |

| Oregon | 523,200 | 53.1% | 50.6% |

| Pennsylvania | 1,611,900 | 55.2% | 51.1% |

| Rhode Island | 162,500 | 54.5% | 51.6% |

| South Carolina | 553,000 | 55.5% | 51.3% |

| South Dakota | 65,400 | 54.5% | 49.7% |

| Tennessee | 901,000 | 55.0% | 51.3% |

| Texas | 2,556,800 | 53.3% | 50.4% |

| Utah | 159,500 | 51.3% | 49.6% |

| Vermont | 87,600 | 51.8% | 50.5% |

| Virginia | 544,500 | 54.8% | 50.9% |

| Washington | 957,600 | 52.7% | 50.0% |

| West Virginia | 312,900 | 55.2% | 50.7% |

| Wisconsin | 554,200 | 53.4% | 50.3% |

| Wyoming | 32,600 | 52.7% | 50.0% |

Source: American Community Survey, 2015 and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2016 (https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/downloads/updated-december-2016-enrollment-data.pdf)

Method: ACS data are used to estimate the share of Medicaid enrollees in each state that are female. Then, these estimates are applied to the most recent available Medicaid administrative enrollment figures from CMS.

| TABLE 3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race and Ethnicity of Women and Girls Enrolled in Medicaid | ||||||||||||

| State | Total | White | African- American | Asian/ Pacific Islander | Hispanic | Other | % White | % African- American | % Asian/ Pacific Islander | % Hispanic | % Other | |

| United States | 40,412,400 | 17,497,800 | 8,158,700 | 1,845,700 | 11,046,500 | 1,863,600 | 43% | 20% | 5% | 27% | 5% | |

| Alabama | 491,300 | 227,900 | 215,500 | 3,300 | 30,000 | 14,700 | 46% | 44% | 1% | 6% | 3% | |

| Alaska | 90,400 | 39,100 | 6,600 | 6,700 | 4,100 | 33,800 | 43% | 7% | 7% | 5% | 37% | |

| Arizona | 920,000 | 326,300 | 53,900 | 17,200 | 429,700 | 92,900 | 35% | 6% | 2% | 47% | 10% | |

| Arkansas | 507,400 | 314,900 | 126,600 | 5,200 | 38,900 | 21,800 | 62% | 25% | 1% | 8% | 4% | |

| California | 6,584,400 | 1,476,200 | 495,300 | 734,700 | 3,635,100 | 243,200 | 22% | 8% | 11% | 55% | 4% | |

| Colorado | 735,100 | 359,500 | 52,700 | 19,800 | 274,100 | 29,000 | 49% | 7% | 3% | 37% | 4% | |

| Connecticut | 413,000 | 186,300 | 73,300 | 9,400 | 130,800 | 13,200 | 45% | 18% | 2% | 32% | 3% | |

| Delaware | 133,200 | 57,900 | 46,800 | 2,300 | 19,200 | 7,000 | 43% | 35% | 2% | 14% | 5% | |

| District of Columbia | 150,000 | 4,600 | 126,300 | 1,300 | 14,400 | 3,400 | 3% | 84% | 1% | 10% | 2% | |

| Florida | 2,348,900 | 875,500 | 592,400 | 35,300 | 775,000 | 70,800 | 37% | 25% | 2% | 33% | 3% | |

| Georgia | 968,300 | 357,800 | 451,100 | 21,100 | 109,700 | 28,500 | 37% | 47% | 2% | 11% | 3% | |

| Hawaii | 181,100 | 23,900 | 1,300 | 52,000 | 29,600 | 74,300 | 13% | 1% | 29% | 16% | 41% | |

| Idaho | 156,900 | 113,400 | 300 | 400 | 31,900 | 10,900 | 72% | 0% | 0% | 20% | 7% | |

| Illinois | 1,679,700 | 655,900 | 475,500 | 61,100 | 443,100 | 44,000 | 39% | 28% | 4% | 26% | 3% | |

| Indiana | 824,000 | 540,300 | 153,700 | 13,300 | 83,400 | 33,400 | 66% | 19% | 2% | 10% | 4% | |

| Iowa | 339,700 | 257,800 | 22,400 | 6,300 | 34,500 | 18,700 | 76% | 7% | 2% | 10% | 6% | |

| Kansas | 209,300 | 120,900 | 23,500 | 5,400 | 45,700 | 13,800 | 58% | 11% | 3% | 22% | 7% | |

| Kentucky | 666,000 | 535,900 | 80,500 | 5,900 | 24,600 | 19,100 | 80% | 12% | 1% | 4% | 3% | |

| Louisiana | 766,400 | 297,500 | 398,000 | 9,300 | 36,500 | 25,000 | 39% | 52% | 1% | 5% | 3% | |

| Maine | 143,900 | 130,100 | 3,500 | 1,500 | 2,700 | 6,200 | 90% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 4% | |

| Maryland | 704,000 | 237,800 | 308,300 | 31,100 | 96,100 | 30,600 | 34% | 44% | 4% | 14% | 4% | |

| Massachusetts | 890,300 | 463,100 | 112,600 | 57,900 | 223,800 | 33,000 | 52% | 13% | 7% | 25% | 4% | |

| Michigan | 1,229,200 | 727,300 | 335,600 | 23,600 | 90,100 | 52,600 | 59% | 27% | 2% | 7% | 4% | |

| Minnesota | 554,600 | 345,200 | 92,500 | 35,100 | 52,100 | 29,800 | 62% | 17% | 6% | 9% | 5% | |

| Mississippi | 377,600 | 141,900 | 216,100 | 1,800 | 10,300 | 7,500 | 38% | 57% | 0% | 3% | 2% | |

| Missouri | 537,300 | 350,200 | 130,400 | 3,800 | 29,400 | 23,500 | 65% | 24% | 1% | 5% | 4% | |

| Montana | 129,200 | 98,100 | 200 | 900 | 6,200 | 23,800 | 76% | 0% | 1% | 5% | 18% | |

| Nebraska | 137,400 | 76,800 | 18,100 | 3,000 | 30,000 | 9,400 | 56% | 13% | 2% | 22% | 7% | |

| Nevada | 330,300 | 124,100 | 47,900 | 18,300 | 116,400 | 23,800 | 38% | 15% | 6% | 35% | 7% | |

| New Hampshire | 98,600 | 83,900 | 2,000 | 1,500 | 7,200 | 3,900 | 85% | 2% | 2% | 7% | 4% | |

| New Jersey | 972,000 | 335,600 | 204,100 | 65,600 | 339,100 | 27,600 | 35% | 21% | 7% | 35% | 3% | |

| New Mexico | 418,300 | 99,300 | 6,400 | 4,200 | 245,100 | 63,300 | 24% | 2% | 1% | 59% | 15% | |

| New York | 3,470,600 | 1,229,000 | 711,900 | 344,500 | 1,072,600 | 112,600 | 35% | 21% | 10% | 31% | 3% | |

| North Carolina | 1,128,100 | 501,700 | 395,000 | 14,200 | 158,900 | 58,200 | 44% | 35% | 1% | 14% | 5% | |

| North Dakota | 51,600 | 36,000 | 2,100 | 600 | 1,300 | 11,600 | 70% | 4% | 1% | 3% | 22% | |

| Ohio | 1,610,100 | 1,016,900 | 400,000 | 21,500 | 93,100 | 78,600 | 63% | 25% | 1% | 6% | 5% | |

| Oklahoma | 426,900 | 234,200 | 35,100 | 5,600 | 62,600 | 89,400 | 55% | 8% | 1% | 15% | 21% | |

| Oregon | 523,200 | 347,800 | 18,000 | 17,900 | 105,600 | 34,000 | 66% | 3% | 3% | 20% | 6% | |

| Pennsylvania | 1,611,900 | 923,000 | 339,000 | 49,500 | 234,700 | 65,700 | 57% | 21% | 3% | 15% | 4% | |

| Rhode Island | 162,500 | 86,000 | 14,600 | 5,700 | 45,600 | 10,600 | 53% | 9% | 4% | 28% | 7% | |

| South Carolina | 553,000 | 241,400 | 251,500 | 4,500 | 32,000 | 23,600 | 44% | 45% | 1% | 6% | 4% | |

| South Dakota | 65,400 | 41,500 | 1,400 | 500 | 3,100 | 18,900 | 63% | 2% | 1% | 5% | 29% | |

| Tennessee | 901,000 | 544,000 | 248,800 | 7,200 | 63,400 | 37,700 | 60% | 28% | 1% | 7% | 4% | |

| Texas | 2,556,800 | 599,900 | 422,700 | 65,000 | 1,414,800 | 54,400 | 23% | 17% | 3% | 55% | 2% | |

| Utah | 159,500 | 108,600 | 2,600 | 3,500 | 35,800 | 9,100 | 68% | 2% | 2% | 22% | 6% | |

| Vermont | 87,600 | 79,500 | 1,000 | 2,600 | 1,700 | 2,800 | 91% | 1% | 3% | 2% | 3% | |

| Virginia | 544,500 | 242,200 | 189,900 | 20,500 | 67,800 | 24,200 | 44% | 35% | 4% | 12% | 4% | |

| Washington | 957,600 | 549,200 | 52,400 | 61,200 | 206,000 | 88,800 | 57% | 5% | 6% | 22% | 9% | |

| West Virginia | 312,900 | 283,100 | 15,400 | 900 | 6,800 | 6,700 | 90% | 5% | 0% | 2% | 2% | |

| Wisconsin | 554,200 | 343,600 | 96,800 | 18,800 | 67,800 | 27,100 | 62% | 17% | 3% | 12% | 5% | |

| Wyoming | 32,600 | 24,000 | 600 | 100 | 5,200 | 2,800 | 74% | 2% | 0% | 16% | 9% | |

Source: American Community Survey 2015 and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2016 (https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/downloads/updated-december-2016-enrollment-data.pdf)

Method: ACS data are used to estimate the share of Medicaid enrollees in each state that are female and the race and ethnicity of these female Medicaid enrollees. Then, these estimates are applied to the most recent available Medicaid administrative enrollment figures from CMS. Note, percentages may not add to 100 percent due to rounding.

| TABLE 4 | |

|---|---|

| Share of Total Births Financed by Medicaid, 2010 | |

| State | Percent |

| United States | 45% |

| Alabama | 53% |

| Alaska | 53% |

| Arizona | 53% |

| Arkansas | 67% |

| California | 48% |

| Colorado | 37% |

| Connecticut | 31% |

| Delaware | N/A |

| District of Columbia | 68% |

| Florida | 49% |

| Georgia | 42% |

| Hawaii | 24% |

| Idaho | 39% |

| Illinois | 52% |

| Indiana | 47% |

| Iowa | 40% |

| Kansas | 33% |

| Kentucky | 44% |

| Louisiana | 69% |

| Maine | 63% |

| Maryland | 26% |

| Massachusetts | 27% |

| Michigan | 45% |

| Minnesota | 44% |

| Mississippi | 65% |

| Missouri | 42% |

| Montana | 35% |

| Nebraska | 31% |

| Nevada | 44% |

| New Hampshire | 30% |

| New Jersey | 28% |

| New Mexico | 53% |

| New York | 46% |

| North Carolina | 54% |

| North Dakota | 29% |

| Ohio | 38% |

| Oklahoma | 64% |

| Oregon | 45% |

| Pennsylvania | 33% |

| Rhode Island | 46% |

| South Carolina | 50% |

| South Dakota | 36% |

| Tennessee | 51% |

| Texas | 48% |

| Utah | 31% |

| Vermont | 47% |

| Virginia | 30% |

| Washington | 39% |

| West Virginia | 52% |

| Wisconsin | 50% |

| Wyoming | 38% |

Source: Anne Markus et al., "Medicaid Covered Births, 2008 Through 2010, in the Context of the Implementation of Health Reform," George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services, October 2016, http://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(13)00055-8/pdf.

End Notes

[1] All states also offered limited coverage for uninsured women ineligible for Medicaid who have a diagnosis of breast or cervical cancer, however these programs do not offer consistent access to primary and preventive care, inpatient care, or long-term care services, see: Judith Solomon, “Medicaid Works: A Critical and Evolving Pillar of U.S. Health Care,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-works-a-critical-and-evolving-pillar-of-us-health-care.

[2] Usha Ranji, Yali Bair, and Alina Salganicoff, “Medicaid and Family Planning: Background and Implications of the ACA,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 3, 2016, http://kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-family-planning-medicaid-family-planning-policy/; prior to the Medicaid expansion, the median eligibility level for parents in 2013 was 61 percent; see Marcha Heberlein, Tricia Brooks, and Joan Alker, “Getting into Gear for 2014: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP, 2012–2013,” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2013.

[3] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid’s Role for Women Across the Lifespan: Current Issues and the Impact of the Affordable Care Act,” December 2012.

[4] Alina Salganicoff et al., “Women and Health care in the Early Years of the Affordable Care Act: Key Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey,” Kaiser Family Foundation, May 2014.

[5] Adam Sonfield, “Why Protecting Medicaid Means Protecting Sexual and Reproductive Health,” Guttmacher Policy Review, March 2017.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Op cit., Kaiser Family Foundation 2012; Kimberly Daniels, William Mosher, and Jo Jones, “Contraceptive Methods Women Have Ever Used: United States, 2982-2010,” National Health Statistics Reports, February 2013, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr062.pdf.

[8] Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020 Topics & Objectives: Family Planning, https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/family-planning.

[9] Op cit., Ranji 2016.

[10] States may not exclude providers due to criteria unrelated to their ability to provide family planning services, such as whether the provider also performs privately funded abortions (federal funds can’t be used for abortion except in cases of danger to the life of the mother, rape, or incest). This guarantee has recently been upheld by several federal courts in light of recent state attempts to prohibit Medicaid funding for services provided at Planned Parenthood.

[11] Op cit., Ranji 2016.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Op cit., Solomon 2016.

[14] Op cit., Ranji 2016.

[15] Michael C. Lu, et al., “Preconception Care Between Pregnancies: The Content of Internatal Care,” Maternal and Child Health Journal, July 2006; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Expanding Medicaid Will Benefit Both Low-Income Women and Their Babies,” April 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Fact-Sheet-Impact-on-Women.pdf.

[16] Kathy Gifford et al., “Medicaid Coverage of Pregnancy and Perinatal Benefits: Results from a State Survey,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2017.

[17] States must evaluate the eligibility for newborns before their first birthday to ensure they stay covered if they remain eligible.

[18] Edwin Park et al., “Frequently Asked Questions About Medicaid,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated March 29, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/frequently-asked-questions-about-medicaid.

[19] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Maternal Depression Screening and Treatment: A Critical Role for Medicaid in the Care of Mothers and Children,” May 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib051116.pdf.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicare’s Role for Women,” May 16, 2013, http://kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/medicares-role-for-older-women/.

[22] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicaid and CHIP: Strengthening Coverage, Improving Health,” January 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/downloads/accomplishments-report.pdf.

[23] Op cit., Kaiser 2012.

[24] Op cit., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2017.

[25] Edwin Park, Judith Solomon, and Hannah Katch, “Updated House ACA Repeal Bill Deepens Damaging Medicaid Cuts for Low-Income Individuals and Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 21, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/updated-house-aca-repeal-bill-deepens-damaging-medicaid-cuts-for-low-income.

[26] Congressional Budget Office, “Cost Estimate: American Health Care Act,” March 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52486.

[27] Leighton Ku and Erin Brantley, “Medicaid Work Requirements: Who’s At Risk?” Health Affairs, April 2017.

[28] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, letter to governors, March 2017, https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/State-Innovation-Waivers/Downloads/March-13-2017-letter_508.pdf.

[29] Jessica Schubel and Judith Solomon, “States Can Improve Health Outcomes and Lower Costs in Medicaid Using Existing Flexibility,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 9, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-can-improve-health-outcomes-and-lower-costs-in-medicaid-using-existing.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise