Opponents of Medicaid expansion claim that states need flexibility to promote personal responsibility, ensure appropriate use of health care services, and require work. These critics seek to impose premiums, cost-sharing charges, and work requirements that go well beyond what the Medicaid statute allows.

A robust body of research shows that imposing premiums and cost-sharing charges on people with low incomes doesn’t ensure appropriate use of health care, but instead keeps people from enrolling in coverage or from getting necessary care. And work requirements are not appropriate for Medicaid, a program intended to provide health care services to people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to get the care they need. Most adult Medicaid beneficiaries are already working, and many of those who aren’t could benefit from the access to health services that Medicaid coverage provides, which in some cases may help them obtain or maintain employment.

States can, however, use Medicaid to employ a number of strategies to promote personal responsibility and work and ensure appropriate use of health care, which would also help lower Medicaid spending and improve beneficiary health outcomes. These alternatives focus on improving the delivery of care instead of imposing harsh requirements that prevent people from getting care in the first place. Many states have already taken advantage of Medicaid’s existing flexibility to move in this direction.

Before health reform, the few states that provided Medicaid coverage to low-income adults without children used section 1115 of the Social Security Act, which allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to approve demonstration projects (also referred to as waivers) to test policies not otherwise permitted under Medicaid by waiving certain provisions of Medicaid law. Such demonstration projects must be “likely to assist in promoting the objectives” of the Medicaid program and must be budget neutral for the federal government (meaning the federal government cannot spend more under a demonstration project than it would have spent if the demonstration hadn’t been approved). This requirement has meant that states often have limited their overall waiver costs by imposing enrollment caps and limits on benefits, and in some cases by charging premiums that generally were not otherwise allowed under Medicaid.[1]

While the Supreme Court made health reform’s Medicaid expansion a state-by-state decision, the expansion provides an explicit pathway for states to provide coverage to all non-elderly adults with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line. States no longer need to use section 1115 waivers to expand eligibility to these people, but waivers are still being used to make other programmatic changes, especially as states continue to consider the Medicaid expansion. The programmatic flexibility a waiver can provide, however, is limited. While HHS has approved the use of premiums in Medicaid expansion waivers, it has not allowed states to condition coverage for beneficiaries with incomes below the poverty line on payment of premiums. Moreover, it hasn’t allowed states to impose cost-sharing charges beyond what Medicaid rules already allow unless the state meets the criteria for cost-sharing waivers set forth in the Medicaid statute.

Supporters of the expanded use of premiums and cost-sharing in Medicaid expansion waivers argue that individuals receiving Medicaid coverage should have some “skin in the game” and be responsible for some of their health care costs. However, research from pre-health reform waivers and other state-funded programs for low-income people shows that charging premiums to low-income people results in many eligible people forgoing or delaying coverage and remaining uninsured. For those with coverage, co-pays and other cost-sharing charges have been shown to keep low-income people from accessing needed care.[2]

Some recent waiver proposals have also sought to impose work or work-search requirements on newly eligible adults. These proposals have ignored the fact that most newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries are working but don’t have access to, or cannot afford, employer-based coverage. Other Medicaid beneficiaries have serious barriers to work, and work requirements could bar them from Medicaid when coverage could increase their chances of becoming and staying employed.

Medicaid expansion waivers approved in Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, and Pennsylvania require newly eligible adults to pay monthly premiums as a condition of coverage.[3] These waivers are supposed to test whether monthly premiums will result in more efficient use of health care services without harming beneficiary health or access to care. For example, Indiana’s Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) 2.0 waiver will test the theory that HIP 2.0 beneficiaries with premiums “…will exhibit more cost-conscious healthcare consumption behavior…” than beneficiaries not subject to premiums.[4] Iowa will use its Medicaid expansion waiver to show how “…the monthly premium does not pose an access to care barrier.”[5]

States are testing the use of premiums despite a longstanding and robust body of research that shows premiums create a barrier to coverage for low-income individuals, especially those living below the poverty line. For example, based on data on the impact that sliding-scale premiums had on low-income people in four states, researchers in a 1999 study developed a model to forecast the effect that premium increases would have on uninsured low-income individuals’ enrollment in coverage. The model estimates that raising premiums from 1 percent to 3 percent of family income will cause the share of eligible, uninsured low-income people who enroll in coverage to fall substantially, from 57 percent to 35 percent.[6]

Evidence from older Medicaid waivers (those that were approved before health reform) shows the harmful effects that premiums have on low-income individuals. For example, in February 2003, HHS approved Oregon’s request to amend its Medicaid waiver to increase premiums on individuals participating in its Medicaid waiver program.[7] A 2004 study found that following these changes, total enrollment in Oregon’s waiver program dropped by almost half. Enrollment of beneficiaries with no income (who were previously exempt from paying premiums) dropped by 58 percent, from 42,000 enrollees in 2002 to 17,500 in October 2003. Nearly one-third of the lowest-income individuals (those with income below 10 percent of the poverty line) found it difficult to pay their monthly premiums, and of those who lost coverage, nearly one-third reported that they lost it because they could not afford to pay their share of the cost. The study found that two-thirds of those who lost coverage remained uninsured at the end of the study period in February 2004.[8]

Utah and Washington had similar experiences. Under an earlier version of its Medicaid waiver, Utah required individuals below 150 percent of the poverty line, including childless adults with no income and parents with income as low as 45 percent of the poverty line, to pay an annual $50 enrollment fee (payable both at initial enrollment and each subsequent year when the individual re-enrolled).[9] A 2004 study found that of those who lost coverage at the time of re-enrollment, nearly one-third cited financial barriers as the primary reason they did not re-enroll. Most of that group said they could not afford the $50 enrollment fee.[10]

In 2002, Washington moved about 25,000 individuals with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line who weren’t eligible for Medicaid to its state-funded Basic Health Plan from other state-funded health insurance programs.[11] About 36 percent of the people being transitioned lost their coverage because they didn’t pay the new premiums, which ranged from $10 to $158 a month based on the individual’s income.[12]

Imposing monthly premiums can negatively affect state budgets as well. Collecting and monitoring monthly premiums can result in higher state administrative costs that outweigh the premiums the state collects. Arkansas legislators recently suspended collecting premiums from adults with incomes between 50 and 100 percent of the poverty line who participate in the state’s “Private Option” Medicaid waiver. The state’s Medicaid agency projects that the waiver’s administrative costs will be cut in half — from $12 million to $6 million — as a result.[13]

The projected savings in Arkansas are consistent with findings of a feasibility study in Arizona. In 2006, Arizona’s Medicaid agency conducted a fiscal impact study for the state legislature to determine how much the state could save from charging premiums as well as the higher co-pays allowed by the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005.[14] The fiscal impact study showed that it would cost the state about $15.8 million to collect premiums and cost-sharing charges while raising only about $2.9 million in premiums and $2.7 million in co-pays.[15]

Medicaid critics often claim that Medicaid beneficiaries use the emergency room (ER) more frequently than adults with other forms of coverage. While this is true, most of these visits are for serious medical problems and not for treatment of non-emergency conditions. In fact, only about 10 percent of ER visits paid by Medicaid in 2008 were for non-emergency conditions — only slightly more than the share of ER visits by people with private insurance (7 percent).[16]

Yet some states continue to propose steep co-pays for Medicaid beneficiaries who use the ER for non-emergency care. The theory behind these co-pays is that they will lead beneficiaries to use more appropriate settings for non-emergency care, such as primary care providers, instead of the ER. A recent study shows, however, that co-pays don’t work in this way. Co-pays for non-emergency use of the ER didn’t change beneficiaries’ use of the ER or primary care.[17]

A large body of research — going back to the 1970s — also shows that cost-sharing for services outside of the ER negatively affects low-income individuals’ use of care. RAND’s Health Insurance Experiment study found that low-income individuals who were subject to cost sharing were significantly less likely to receive effective acute care than those not subject to cost-sharing. In Washington, 20 percent of those enrolled in the state-funded Basic Health program — a program that covered low-income adults with incomes up to 200 percent of the poverty line who were not eligible for Medicaid — went without needed care over a five- to six-month period as a result of the program’s increased cost-sharing requirements in January 2004.[18]

Cost-sharing can pose significant financial strain on individuals who have limited resources. In Washington, the increased co-pays caused one-third of those enrolled in the state’s Basic Health program to skip or make smaller payments on other bills.[19] Similarly in Utah, where co-pays under the state’s waiver were slightly above Medicaid’s permissible amounts, 40 percent of those participating in the state’s Medicaid waiver in 2003 said that the co-pays weren’t affordable.[20]

As with collecting premiums, the substantial administrative costs associated with charging co-pays for non-emergency use of the ER can outweigh the revenue the co-pays generate. For example, in 2008, Texas conducted a fiscal analysis on the cost effectiveness of charging a co-pay for non-emergency use of the ER in its Medicaid program. While the state estimated it would save about $153,000 over a two-year period from ER diversions, it would have cost the state $2.9 million to collect the payments.[21] The state ultimately decided notto institute the co-pays.

Despite the fact that HHS recently stated that “…work initiatives are not the purpose of the Medicaid program and cannot be a condition of Medicaid eligibility,” some governors and state legislators continue to promote linking Medicaid coverage to work or work-search requirements.[22]

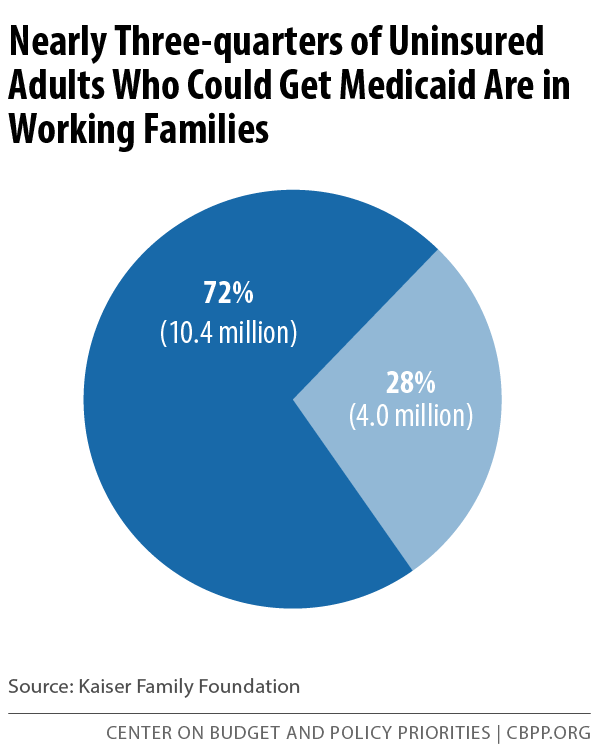

Work requirements conflict with Medicaid’s basic purpose of providing health care to people who can’t otherwise afford it, and such requirements are not necessary to ensure that many beneficiaries are employed: 72 percent of uninsured adults who are eligible for Medicaid coverage live in a family with at least one full-time or part-time worker.[23] (See Figure 1.)

More than half (57 percent) of these adults are working full- or part-time themselves.[24] The overwhelming majority of workers earning less than 138 percent of poverty — 81 percent — don’t have coverage through their employer because their employer either doesn’t offer it or it is unaffordable to them.[25]

Moreover, tangible reasons, such as having a chronic condition or serious mental illness, can preclude many of the remaining adults from joining the workforce. The Kaiser Family Foundation recently looked at the main reasons for not working among unemployed, uninsured adults likely to gain Medicaid coverage if their state adopted the Medicaid expansion. It found that 29 percent were taking care of a family member, 20 percent were looking for work, 18 percent were in school, 17 percent were ill or disabled, and 10 percent were retired.[26]

States can employ a variety of approaches to ensure appropriate use of health care services and encourage work without creating barriers to coverage and care. Many of these approaches have been shown to improve health outcomes for beneficiaries and lower spending. Many states are taking advantage of these options to deliver more coordinated care, often focusing on beneficiaries with chronic conditions who use the most care. (See the appendix for the technical details of the Medicaid options that allow states to achieve these results.)

A relatively small number of Medicaid beneficiaries’ ER visits are for non-emergencies; most ER visits are for serious problems, the evidence shows. Recent efforts indicate, however, that states can reduce ER use by expanding access to primary care services and targeting interventions at populations that frequently use the ER.

- Georgia. Using a $2.5 million grant from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Georgia implemented an ER diversion project. The project established four primary care sites in rural and underserved areas of the state with extended or weekend hours to help redirect care from the ER to more appropriate settings. The four cities served about 33,000 patients and saved the state about $7 million over a three-year period, according to CMS.[27]

- Indiana. Indiana’s successful effort to reduce inappropriate use of the ER started in 2010, well before HHS approved its new waiver allowing the state to charge $25 co-pay for non-emergency use of the ER. All managed care plans in Indiana participate in the effort, known as the Right Choices Program, which is designed to prevent unnecessary and inappropriate use of care by those Medicaid beneficiaries who use the most services. Primary care providers coordinate all specialty care, hospital, and prescription services for these beneficiaries. As a result of this initiative, Wellpoint, one of Indiana’s Medicaid managed care plans, has seen ER use among its Medicaid enrollees decrease by 72 percent.[28]

- Minnesota. Building upon its existing managed care program, Minnesota implemented an innovative model to lower Medicaid spending and improve beneficiary health outcomes. The state allows its Medicaid health plans to partner with different types of organizations to deliver integrated medical, behavioral, and social services. One such organization is Hennepin Health, an accountable care organization that comprises a wide variety of providers — from primary care doctors to nutritionists to housing counselors — and treats patients based on their individual needs.[29] This initiative is still relatively new, but preliminary data show that Hennepin Health has reduced ER use. ER visits by Hennepin Health’s members dropped by 9.1 percent between 2012 and 2013.[30]

Hennepin Health also implemented a separate initiative to target members who frequently use the ER or have high inpatient hospital admission rates. Since partnering with the Hennepin County Medical Center Coordinated Care Clinic to provide comprehensive care to this group, Hennepin Health has seen a 50 percent drop in hospitalizations. [31]

- New Mexico. In 2006, New Mexico created a statewide 24/7 nurse advice hotline, which is available to all state residents regardless of their coverage status. The state has saved more than $68 million in health care expenditures with 65 percent of callers diverted from the ER. The advice line has been used by 75 percent (1.5 million) of the state’s roughly 2 million residents, and the vast majority of callers (85 percent) have followed the nurses’ instructions. The nurse advice line has also been instrumental during public health crises. During the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009, nurses were able to effectively stem the spread of the disease in the state. By contacting on-call doctors to prescribe Tamiflu to callers presenting flu symptoms, the nurses kept thousands of patients out of the ERs and doctor’s offices.[32]

- Washington. In June 2012, Washington moved Medicaid beneficiaries from fee-for-service to managed care and required hospitals to adopt seven best practices aimed at reducing unnecessary ER use.[33] By June 2013, ER visits among Medicaid beneficiaries had dropped by 9.9 percent, and non-emergency ER visits by the group had fallen 14.2 percent. The adoption of the seven best practices, in combination with the rollout of Medicaid managed care, saved the state about $34 million in state fiscal year 2013.[34]

- Wisconsin. The Milwaukee Health Care Partnership, an organization composed of local and state government, medical providers, and hospitals that serves mostly Medicaid enrollees and uninsured individuals, began an initiative to reduce inappropriate ER use in 2007. Under the initiative, the Partnership identifies frequent ER users, makes primary care appointments for them, and educates them on proper ER use. In 2012, the Partnership reduced ER visits by 44 percent among those who kept their scheduled primary care appointment.[35]

States can lower Medicaid spending by improving the care and health outcomes for individuals with chronic conditions who use a lot of health care services. About 1 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries account for 25 percent of total Medicaid expenditures. Within this group, 83 percent have at least three chronic conditions, and more than 60 percent have five or more.[36] Several states have lowered their Medicaid spending by improving health care service use (and beneficiary health outcomes) through managed care, the implementation of health homes, and other models.[37]

- Missouri. In 2011, CMS approved Missouri’s health homes initiative, which targets individuals with a mental illness and one of the following chronic conditions: diabetes, asthma/pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, developmental disability, obesity, and tobacco use. Over a two-year period, among individuals enrolled in health homes, blood pressure dropped by six points and LDL (bad cholesterol) fell by 10 percent. Hospitalizations of patients enrolled in the state’s Community Mental Health Center (CMHC) health home dropped from 33.7 percent in 2011 to 24.6 percent in 2012. The CMHC health home saved $15.7 million in its first 18 months.[38]

- North Carolina. Approximately 80 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries in North Carolina are enrolled in the Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC) program, a network of community health providers that links beneficiaries to a medical home. The state pays the primary care practices a management fee to coordinate each individual’s care. According to one study, the CCNC program cut the number of ER visits for children with asthma by 8 percent, and the number of hospitalizations among the same group by 34 percent, in its first year.[39] The program is projected to save North Carolina $160 million per year.

The state has also established a CCNC Transitional Care program to prevent hospital readmissions by providing recently discharged patients with support, such as medication management, patient education, and appropriate follow-up care. As a result of this program, hospital readmissions have fallen by 20 percent. Moreover, data have shown that the program’s success is evident a year after the patient’s discharge, with reduced likelihood of a second and third readmission during the following year.[40]

- Vermont. In 2011, Vermont implemented the Vermont Chronic Care Initiative, a statewide program that provides care coordination and case management services to beneficiaries with one or more chronic conditions such as asthma, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and mental health and substance use disorders.[41] The state reported that individuals participating in the program improved their adherence to proven care regimens relative to people with the same conditions who didn’t participate in the program. The state also reported that ER use and inpatient hospital admissions dropped by 10 percent and 14 percent, respectively, among participants.[42]

Many Medicaid beneficiaries who are not working have some underlying reason, such as a disability or a chronic condition that makes it difficult for them to find and maintain employment. The unemployment rate in 2012 for individuals with mental illness was 17.8 percent. The National Alliance for Mental Illness has concluded that six in ten unemployed adults with mental illness could succeed at work with appropriate employment supports such as job training, but only 1.7 percent of adults receiving state mental health services also received supportive employment services in 2012.[43]

States can offer supportive employment services to individuals with mental illness through their Medicaid programs. In 2007, Iowa became the first state to receive CMS approval to amend its Medicaid state plan to include a supportive employment program. Under Iowa’s program, the state receives federal Medicaid dollars to help such individuals find and maintain employment. Other states have followed Iowa’s lead, including California, Delaware, Mississippi, and Wisconsin.

Each state’s approach to supportive employment services is modeled off of evidence-based programs, such as the Individual Placement and Support model, which have been shown to help participants find and maintain employment. States provide an array of services to qualifying individuals, such as skills assessment, assistance with job search and completing job applications, job development and placement, job training, and negotiation with prospective employers. Some states even help individuals interested in self-employment by helping the individual identify potential business opportunities and develop a business plan.

Some recent Medicaid expansion proposals run counter to the objectives they seek to promote. Charging low-income people premiums and excessive co-pays does little to improve use of health services, while erecting barriers to coverage and access to needed care and pushing up administrative costs. Imposing work requirements on low-income adults is inappropriate and can be counter-productive; placing such requirements on people who aren’t working due to a chronic condition or mental illness can cause them to remain out of Medicaid and uninsured, with the result that they miss out on mental health, substance abuse, or other treatment that might help them become more employable.

States should focus on the opportunities they have to transform Medicaid service delivery. Improvements in the coordination and integration of care can increase appropriate use of the health care system, lower Medicaid spending, and improve health and employment outcomes.

Appendix

Existing Medicaid Delivery and Payment Reform Flexibilities

The health reform law created health homes to give states a way to improve the health of individuals with chronic conditions and to lower program costs through reductions in ER use and hospital admissions and readmissions. Health home providers are interdisciplinary teams of health care providers, which can include physicians, nurses, social workers, and other professionals. Health homes bring together and coordinate all primary, acute, and behavioral health (including treatment for mental illness and substance use disorders), as well as home care and other services for individuals with chronic conditions.

States have flexibility in designing their health home programs; they can include individuals with both a persistent physical health condition such as heart disease or diabetes and serious mental illness, two or more chronic conditions, and those with one chronic condition and risk of a second.[44] Missouri’s health home initiative, for example, is targeted to individuals with a mental illness who also use tobacco or have at least one chronic physical condition including diabetes, asthma/pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, developmental disability, and obesity.[45]

States also have considerable flexibility in how they pay for health home services. While most states pay participating health home providers a flat monthly per-beneficiary amount, they can provide different payments according to the severity of an individual’s chronic conditions or the capacity and performance of the health home in caring for the sickest beneficiaries. Oregon, for example, uses a tiered approach with three tiers that correspond to the health home’s ability to meet state standards in areas such as access to care, accountability, ability to provide comprehensive whole-person care, and integration to care. The health homes are then paid based on how well they meet the standards.

States implementing health homes receive federal funds at a 90 percent match rate for expenditures for health home services such as care management, care coordination, and referrals to community and social support services. The enhanced match is only available for the first eight fiscal quarters that a health home’s state plan amendment (SPA) is in effect. States can also receive federal match (at the state’s regular match rate) for activities needed to plan and implement health home initiatives, such as conducting feasibility studies, obtaining provider and other stakeholder feedback, and outreach activities, regardless of whether the state ultimately decides to implement a health home. [46]

More information on health homes is in CMS guidance at http://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/medicaid-state-technical-assistance/health-homes-technical-assistance/health-home-information-resource-center.html.

Integrated care models (ICMs) encompass several health care delivery and payment reforms, including health homes that reward coordinated, high-quality care. ICMs are designed to move states away from the volume-based fee-for-service system in which providers get paid for each service they deliver. These initiatives reward providers who lower costs while improving beneficiary health.

States can deliver Medicaid services through an ICM in several ways in addition to health homes:

- Patient-centered medical home. Patient-centered medical homes provide coordinated and integrated care based on an individual’s health needs. A lead physician arranges appropriate care with other physicians as well as support services that address both health care and other needs such as nutrition and housing that can affect health. The key difference between a patient-centered medical home and a health home is that patient-centered medical homes are available to all individuals but only individuals with chronic conditions can enroll in a health home.

- Accountable care organization. An accountable care organization (ACO) is a provider-run organization in which participating providers are collectively responsible for coordinating the care of enrollees in the ACO. An ACO is similar to a managed care plan, except that providers, not a health plan or insurer, are in charge of care coordination. The participating providers may also share in savings that result from improved efficiency and improvements in quality of care.

An example of an ICM is a program in Minnesota that combines traditional Medicaid managed care with an ACO. Metropolitan Health Plan, one of Minnesota’s four Medicaid managed care plans, partners with Hennepin Health, the ACO, to provide health care services to the ICM’s target population, low-income adults newly eligible for Medicaid who reside in Hennepin County (the state’s most populous county as well as where Minneapolis is located).

States have flexibility as to how they pay providers participating in ICMs. States can pay case managers a capitated monthly amount to coordinate and locate health care services for individuals and to monitor delivery of the services to their patients. States can also combine these monthly capitated amounts with additional incentive payments tied to improved performance on quality and cost measures. These incentive payments come from the savings that result from improvements in quality and reduced costs and are shared among the highest-performing providers, which is why this type of arrangement is referred to as a shared-savings model.

States may also allow participating providers to use the savings to invest in expanded services with the expectation that providing these additional services will further reduce future health care costs. Minnesota, for example, allows Hennepin Health to use its savings to invest in services that Medicaid doesn’t ordinarily cover, such as intensive behavioral health care management or placement in stable housing. In addition to reducing future health care costs, the state expects these investments to also lower costs in other service areas, such as emergency shelters, detoxification centers, and jails.[47]

Implementing an ICM requires an amendment to a state’s Medicaid state plan. However, if a state wants to target an ICM to specific populations, geographic areas, or vary services for different groups, the state needs a Medicaid waiver. Oregon has a Medicaid waiver that allows it to contract with Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs), which in most cases, only operate within certain areas of the state. Moreover, the waiver allows CCOs to offer different services to members based on their specific health care needs.

More information on ICMs is in a series of State Medicaid Director Letters and State Health Official Letters from CMS:

- SMDL# 12-001 - http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SMD-12-001.pdf

- SMDL #12-002 - http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SMD-12-002.pdf

- SMDL #13-005 - http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/Downloads/SMD-13-005.pdf

- SHO #13-007 - http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SHO-13-007.pdf

Targeted Case Management (TCM) allows states to provide case management services that help eligible individuals obtain needed medical, social, education, and other services. TCM allows states to receive federal matching funds to pay for case managers who assess individuals’ needs, develop care plans, refer individuals to services, and monitor health care use. TCM differs from care coordination in that it allows case managers to coordinate education and social services — not just health services — that may be needed to deal with a beneficiary’s health care condition. For example, a case manager could help relocate a family when a child has elevated blood lead levels.

1915(i) Home- and Community-Based Services

The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 authorized this option to allow states to provide home- and community-based services (HCBS) to individuals who don’t meet the standards for receiving care in an institution such as a nursing home. Before enactment of 1915(i), states could only provide HCBS through a waiver and then only when a beneficiary would need institutional care in the absence of the HCBS. The option allows Medicaid beneficiaries in need of long-term services and supports to receive these services in their own home or community before they get to the point of needing institutional care. These programs serve a variety of populations, including individuals with disabilities. To implement this option, states must submit a SPA specifying their eligibility criteria and which services they intend to offer.

This option is particularly important in allowing states to provide HCBS to individuals with mental health and substance use disorders. Because Medicaid generally doesn’t cover care in institutions for people with mental illness and substance use disorders, these beneficiaries were shut out of HCBS waiver programs that require individuals to show that they would be eligible for and receive institutional care covered by Medicaid but for the provision of HCBS.

Using 1915(i), states can offer HCBS to specific, targeted populations, such as individuals with HIV/AIDS or chronic mental illness, and can vary the benefit packages in order to tailor the services to best suit the needs of the target populations. For example, states such as Iowa, Delaware, and Wisconsin provide supportive employment services to help encourage work and work opportunities for their 1915(i) service populations.

More information on 1915(i) HCBS is in CMS guidance at http://medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Long-Term-Services-and-Supports/Home-and-Community-Based-Services/Home-and-Community-Based-Services-1915-i.html.

States have increasingly used managed care since the early 1980s to deliver health care to Medicaid beneficiaries. As the name implies, managed care plans seek to manage how health care services are delivered and used in order to reduce program costs and improve health care quality and health outcomes. States generally contract with a managed care organization that accepts a set payment per member per month — called a capitation payment — to deliver a defined package of Medicaid benefits to beneficiaries enrolled in the plan.[48]

While 39 states including the District of Columbia already use managed care to deliver comprehensive Medicaid services, the role of managed care in Medicaid continues to grow.[49] States currently using fee-for-service are starting to shift some groups to managed care and states already using managed care are expanding to new areas of the state as well as to beneficiaries with higher health care needs, such as those who receive long-term services and supports.

More information on managed care options is in CMS guidance at http://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/delivery-systems/managed-care/managed-care-site.html.

In July 2014, CMS launched the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program (IAP), which provides technical assistance to states interested in reforming their delivery and payment systems. While the IAP doesn’t fund reform initiatives, it provides states with recommendations, strategically targeted resources, and other technical assistance in four areas: (1) identification and advancement of new models; (2) data analytics to target interventions and maximize efficiencies; (3) improved quality measurements; and (4) best practices. In the July 2014 guidance, CMS noted that IAP’s first focus area would be on beneficiaries with substance use disorders, but it recently announced that IAP will also focus on helping states address the needs of beneficiaries using a high level of services, move beneficiaries receiving long-term services and supports out of institutions and back into the community, and assist with initiatives that integrate physical and mental health.

More information on the IAP is in CMS guidance at http://medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/innovation-accelerator-program/innovation-accelerator-program.html

For more information on how to target Medicaid beneficiaries with high health care use, refer to the CMCS Informational Bulletin at: http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/CIB-01-16-14.pdf

For more information on how to reduce non-emergent use of the ER, refer to the CMCS Informational Bulletin at: http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/CIB-01-16-14.pdf