Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance issued in January 2018 allows states — for the first time — to take Medicaid coverage away from people not engaging in work or work-related activities for a specified number of hours each month. CMS has already approved work requirement policies in Kentucky, Indiana, Arkansas, and New Hampshire — although a federal court vacated its approval of Kentucky’s proposal — and other states are seeking approval for similar approaches. The guidance follows unsuccessful attempts by congressional Republicans to allow states to tie Medicaid eligibility to work as part of bills to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

State proposals for Medicaid work requirements will cause many low-income adults to lose health coverage, including people who are working or are unable to work due to mental illness, opioid or other substance use disorders, or serious chronic physical conditions, but who cannot overcome various bureaucratic hurdles to document that they either meet work requirements or qualify for an exemption from them. These coverage losses will not only reduce access to care and worsen health outcomes, but will likely make it more difficult for many people to find or keep a job. Thus, Medicaid work requirements may be self-defeating on their own terms.

CMS argues that work requirements will “promote better… health” because they will increase employment and thereby improve health and well-being.[1] These claims, however, are not based on evidence and do not withstand scrutiny.

-

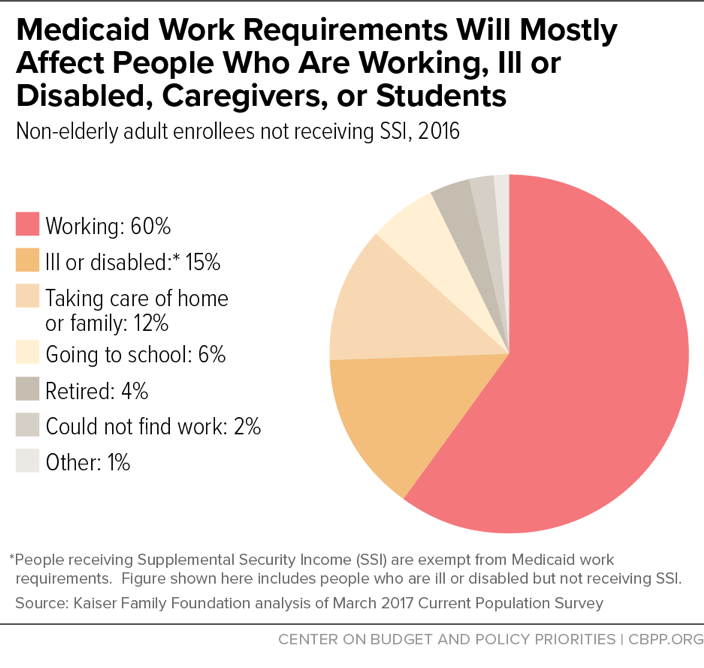

Work requirements will make it harder for most adult beneficiaries — the lion’s share of whom are already working or are ill, disabled, caregivers, or in school — to get and stay covered. Supporters of work requirements generally say that these policies target only people who are not working, actively seeking work, caregivers, in school, or unable to work because of an illness or disability. The CMS guidance, however, allows states to apply work requirements to nearly all non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees, except pregnant women and some people with disabilities. Of the roughly 25 million people nationally who could be subject to work requirements, 60 percent are already working (see Figure 1), and 79 percent have at least one worker in the family. Of those who aren’t themselves working, more than 80 percent are in school or report an illness, disability, or caregiving responsibilities that keep them from working. Yet states could require most of these 25 million enrollees to meet burdensome paperwork and documentation requirements to prove that they are working or volunteering sufficient hours each month or meet the criteria for an exemption.

The unfortunate reality is that, for the large majority of enrollees who are already working or face serious barriers to employment, work requirements have little or no possible benefit. But they will add red tape and bureaucratic hurdles that will cause some of these people to lose coverage. Documentation and paperwork requirements have been repeatedly shown to reduce enrollment in Medicaid across the board,[2] and people with serious mental illness or physical impairments may face particular challenges in meeting these new documentation and paperwork requirements.

Bearing out these concerns, studies of state Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) programs have found that state errors in administering work requirements are common, and people with disabilities, serious illnesses, and substance use disorders may be disproportionately likely to lose benefits, even when they should be exempt. Other enrollees could lose coverage because they are between jobs even though they are actively seeking work, or because their disability or illness— while a serious obstacle to work — does not meet the specific criteria for an exemption laid out in a state’s policies.

Still other enrollees may lose or see interruptions in coverage because their work hours fluctuate from month to month, sometimes falling below required thresholds. Fluctuating hours are particularly common in the two industries with the largest number of Medicaid enrollees: restaurant/food services and construction. Among working low-income adults who could be subject to Medicaid work requirements, nearly half would fail to meet an 80-hour-per-month work requirement like Kentucky’s in at least one month during the year.

Overall, a substantial majority of those losing coverage due to work requirements would be people who are working or who should qualify for exemptions, but fail to overcome the new documentation requirements and other hurdles to maintain their coverage, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis concluded.

-

Work requirements are unlikely to promote employment and may be counterproductive. The CMS guidance offers no evidence that Medicaid work requirements will increase employment. As discussed below, research on work requirements in other programs finds that they generally have only modest and temporary effects on employment, failing to increase long-term employment or reduce poverty.

Results in Medicaid are likely to be just as disappointing, and could be worse, for several reasons. First, as noted, most of those affected by the requirements are either already working or face major barriers to work. Second, Medicaid enrollees targeted by work requirement proposals already have a strong incentive to work: without working, they can get health care but usually little other assistance, and they generally are very poor. Enrollees who are seemingly able to work but aren’t employed typically lack not motivation, but work supports such as job search assistance, job training, child care, and transportation assistance; they may also face challenges such as an undiagnosed substance use disorder, domestic violence, the need to care for an ill family member, or a housing crisis. State Medicaid programs generally are not well equipped to provide or connect families with work support services, which are already oversubscribed in most states. Moreover, the CMS guidance does not require states to offer any work supports in tandem with instituting work requirements — in fact, it prohibits them from using federal Medicaid funding to do so.

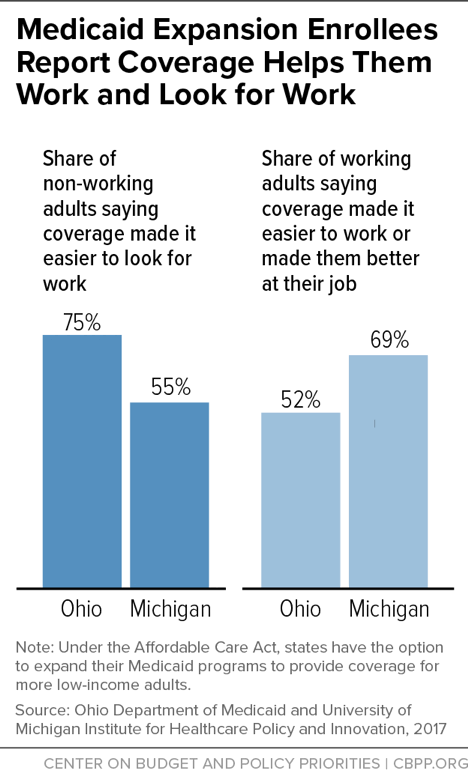

Finally, health coverage is itself an important work support. As a Kaiser Family Foundation review of the available research concludes, “access to affordable health insurance has a positive effect on people’s ability to obtain and maintain employment.”[3] Having health care helps people work and look for work, and taking it away will likely make it harder for some to keep and find work. For example, among non-working adults gaining coverage through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan, majorities said having health care made it easier to look for work. And among working adults, majorities said coverage made it easier for them to work or made them better at their jobs. (See Figure 2.) Moreover, health problems are a common cause of job loss; for example, a person coping with diabetes or depression may lose his or her job because the condition worsens. If job loss also leads to loss of health care and access to treatment, people will only find it harder to get back on their feet.

-

The primary effect of work requirements will be less access to care, worse health outcomes, and less financial security. States themselves project significant coverage losses from work requirements, with Kentucky estimating that 15 percent of all adult Medicaid enrollees — at least 97,000 people — will lose coverage due to work requirements and other provisions of its waiver. As discussed below, studies of both the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and pre-ACA coverage expansions find that they increased access to care — including preventive care, mental health and substance use treatment, and appropriate management of chronic conditions — and improved enrollees’ financial security and health outcomes. For those losing coverage due to work requirements, these gains will be reversed.

Moreover, two groups for whom coverage losses and interruptions in coverage are especially harmful — people with serious chronic health conditions, including mental illness, and people with substance use disorders — make up a large fraction of those likely to lose coverage due to work requirements. An Ohio study found that nearly one-third of adults enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion have a substance use disorder, while 27 percent have been diagnosed with at least one serious physical health condition, such as diabetes or heart disease, just since enrolling in Medicaid. A Michigan study found that among non-working Medicaid expansion enrollees, 72 percent have a serious chronic physical health condition, while 43 percent have a mental health condition, often depression.

For people with these conditions, even the temporary loss of access to medications or other treatment could be harmful or sometimes catastrophic. This is one reason why major physician organizations — including the American Medical Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association, and American Psychiatric Association — oppose Medicaid work requirements.[4]

CMS has already approved waivers in four states — Kentucky, Indiana, Arkansas, and New Hampshire — that would take Medicaid coverage away from people not meeting work requirements, although a federal court rejected CMS’ approval of Kentucky’s policy. These waivers require enrollees to demonstrate that they are working, participating in other qualifying activities, or meet the criteria for exemptions in order to maintain Medicaid coverage.

CMS’ guidance offers states wide latitude in designing work requirements. These policies can apply to nearly all non-elderly Medicaid enrollees, except pregnant women, people who are medically frail,a and those who qualify for Medicaid because they receive disability benefits from the Social Security Administration. (As a Kaiser Family Foundation study has found, almost 60 percent of non-elderly adults with disabilities who are covered by Medicaid — about 4.9 million people — do not receive disability benefits.b)

The guidance also gives states broad scope in determining what activities satisfy the work requirement. It notes that states are required to comply with all civil rights laws, including the Americans with Disabilities Act, which means that states are required to provide “reasonable accommodations” for people with disabilities who are subject to the work requirement. But the guidance does not specify what accommodations are required. And it does not require states to couple work requirements with services that could help people find and keep a job, such as job search assistance, job training, transportation, and child care — nor are states allowed to use federal Medicaid funds for such services.

The work requirement that CMS approved in Kentucky, for example, applies to most non-elderly adults who aren’t receiving disability benefits, taking care of a child or an adult with a disability, or full-time students. Enrollees subject to the work requirement must work or engage in qualifying work activities such as job training, job search, substance use treatment, or volunteer work for at least 80 hours per month to maintain Medicaid coverage. Enrollees are also treated as meeting Medicaid work requirements if they are enrolled in SNAP or TANF and are meeting or exempt from work requirements in those programs.

Other states’ pending and approved work requirement proposals are similar to Kentucky’s, with some differences in exemption criteria, qualifying work activities, and hours requirements.c

aMedicaid regulations define “medically frail” individuals as “individuals with disabling mental disorders (including children with serious emotional disturbances and adults with serious mental illness), individuals with chronic substance use disorders, individuals with serious and complex medical conditions, individuals with a physical, intellectual or developmental disability that significantly impairs their ability to perform one or more activities of daily living, or individuals with a disability determination based on Social Security criteria.” 42 CFR §440.315(f).

b MaryBeth Musumeci, Julia Foutz, and Rachel Garfield, “How Might Medicaid Adults with Disabilities be Affected by Work Requirements in Section 1115 Waiver Programs?” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 26, 2018, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-might-medicaid-adults-with-disabilities-be-affected-by-work-requirements-in-section-1115-waiver-programs/.

c MaryBeth Musumeci, Rachel Garfield, and Robin Rudowitz, “Medicaid and Work Requirements: New Guidance, State Waiver Details, and Key Issues,” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 16, 2018, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-and-work-requirements-new-guidance-state-waiver-details-and-key-issues/.

Work requirements ostensibly aim to affect only the small minority of non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees who are not working, in school, caregivers, or unable to work due to an illness or disability. In reality, however, these policies will create new documentation requirements and other burdens that will put coverage at risk for a much broader group of enrollees. As a result, as noted above, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis finds that the large majority of those likely to lose coverage due to work requirements are working people and people who should be eligible for exemptions, but who lose coverage due to administrative burdens or red tape.[5]

Most Medicaid enrollees who can work are already working. Nearly 80 percent of adults with Medicaid coverage live in working families, and 6 in 10 are working themselves.[6] But if a work requirement is imposed, beneficiaries who work or participate in other eligible activities will have to jump through bureaucratic hoops to establish compliance. They could lose coverage due to failure to submit the right paperwork on time, administrative errors, or if they cannot get enough hours one month or find themselves between jobs.

Some Medicaid enrollees who are working will lose coverage due to increased red tape. State work requirement policies generally require enrollees to demonstrate not just that they are working, but that they are working a sufficient number of hours each month (or each week). This means that they will need to regularly submit paystubs, timesheets, or other documents, potentially from multiple employers. While challenging enough for employees, such requirements will be even more burdensome for people who are self-employed, who may lack such documents altogether, and for people who are trying to prove that they are engaged in sufficient hours of job training, job search, or other qualifying work activities. Enrollees participating in non-work qualifying activities may also not realize that they can continue receiving Medicaid if they report these activities.[7]

Meeting the reporting requirements may also involve taking time off work to visit an eligibility office, waiting to get through to a caseworker, or using online portals that aren’t available to people without access to a computer. Backlogs in processing paperwork, which the additional administrative burdens related to work requirements will almost certainly worsen, can cause delays or mistakes affecting coverage for working individuals. Adding to these challenges, some states propose to vary the required number of hours of engagement over time, creating additional confusion and potential for error for both enrollees and caseworkers. Arkansas’ policy, meanwhile, requires beneficiaries to report their hours for the previous month by the fifth of each month; any hours reported after that date do not count toward the state’s minimum hourly requirement.[8] Under such a restrictive approach, some beneficiaries who are complying with the work requirement will likely still lose coverage. In the first month of implementation, fewer than 6 percent of those who were required to report successfully navigated Arkansas’ complex requirements and reporting structure to log their hours.[9]

Further, many Medicaid beneficiaries work in jobs with variable hours or experience spells of involuntary unemployment. For example, the two industries with the largest number of Medicaid enrollees are restaurant/food services (employing 1.5 million Medicaid enrollees in 2016) and construction (employing 1 million). These are industries in which work hours can fluctuate substantially from week to week and month to month.[10] Under Kentucky’s CMS-approved policy, which requires 80 hours of work activities per month, a restaurant worker who can get only 78 hours of work during a slow month could lose his Medicaid coverage — even if he worked 90 hours the previous month, and even if the employer required him to be available for 160 hours that month (40 hours each week) but only provided 78 hours of work. (To stay covered, he would have to work more than 80 hours the following month or pass a financial or health literacy course.) Likewise, a construction worker could lose coverage if she were unable to find work for a month or two, even if she consistently worked 80 or more hours the previous several months.

Overall, a large share of low-wage workers will fail to meet an 80-hour-per-month work requirement like Kentucky’s at least some of the time, analysis of 2012-2013 Survey of Income and Program Participation data shows. Among low-income working adults who could be subject to Medicaid work requirements, 46 percent worked fewer than 80 hours at least one month out of the year, putting them at risk of losing health coverage under Kentucky and other states’ approved or pending waivers. Even among those who worked at least 1,000 hours over the course of the year — or about 80 hours per month on average — 25 percent would have failed to meet Kentucky’s work requirement in at least one month.[11]

Most Medicaid beneficiaries who are not employed and therefore could lose coverage under a work requirement report significant barriers to employment. Among non-working non-elderly adults with Medicaid who aren’t eligible for disability benefits through the Social Security Administration, 36 percent report that an illness or a disability keeps them from working. Another 30 percent say they are taking care of home or family, and 15 percent are in school.[12]

Physical and behavioral health conditions that limit an individual’s ability to work are much more common among low-income households than among the general population, research shows.[13] The CMS guidance acknowledges that many people with Medicaid coverage have health conditions that prevent them from working, and it says states should design their waivers so that people don’t lose Medicaid coverage as a result. Yet the approved and proposed work requirement policies will not accomplish this. On paper, state policies exempt people who can’t work, including those with acute medical conditions documented by a doctor and those who are medically frail (see box). But in practice, these exemptions are insufficient to protect people who are unable to work, for several reasons.

First, some people with severe barriers to work, such as those with substance use disorders (SUDs) or other chronic conditions, may not be eligible for an exemption. The definition of medically frail is limited and excludes large numbers of people with serious health conditions that keep them from working or allow them to work only intermittently. Moreover, states largely rely on medical claims data to determine who is medically frail, but claims data won’t be an effective means of identification for some people, including those with insufficient claims history, untreated conditions, or multiple chronic conditions. The medically frail category may also fail to capture the many people with health conditions that sometimes allow them to work and sometimes don’t.

Likewise, people with SUDs such as opioid use disorder are often unable to work, and the CMS guidance says that work requirements should not be a barrier to coverage and care for these individuals. But Kentucky’s waiver, for example, does not, as a general rule, exempt people with SUDs from work requirements.[14] Instead, it allows them to count their SUD treatment as a qualifying activity. That means that, to meet Kentucky’s work requirement on this basis, people with SUDs would have to be in treatment 80 hours per month. That is likely to be feasible only if they are in residential treatment, which is often not the most appropriate form of treatment for their condition. People with SUDs who are receiving treatment in a non-residential setting, as well as people who exit a residential treatment program without immediately finding a job, are at high risk of losing their Medicaid coverage and with it access to the primary care, mental health services, and outpatient SUD treatment that could help them regain their health and rejoin the workforce. And people with undiagnosed SUDs may be unable to gain coverage — and with it, access to treatment — in the first place.

Second, state work requirement policies put the burden on beneficiaries to prove that they qualify for an exemption. Most Medicaid caseworkers don’t deal personally with applicants or beneficiaries, and (for good reason) they don’t have access to private medical records. Thus, low-income individuals would have to understand that they qualify for an exemption, get a doctor to document their condition, and submit the form for processing by state workers. Documentation and paperwork requirements have been shown to reduce enrollment in Medicaid across the board,[15] and the cumbersome process for claiming an exemption may pose a particular obstacle for enrollees with physical disabilities that limit mobility, substance use disorders, or mental health conditions. As Harvard Medical School Professor Richard Frank explains, “The burden of proving medical frailty in the Kentucky waiver program will generally fall on the recipient. In this case [of people with mental illness], that means it falls on a person with an illness that interferes with cognition, executive function and mood.”[16]

Third, experience in SNAP and TANF shows the difficulty of screening for exemptions from work requirements. A 2016 investigation by the USDA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that some states were failing to administer the SNAP work requirements effectively and accurately. State officials used terms such as “administrative nightmare” and “operational nightmare” to describe implementing the requirements. The OIG report highlighted instances of states improperly applying the requirements, resulting in the termination of SNAP benefits for individuals who qualified for an exemption.[17]

Another evaluation (in Ohio) of implementation of the SNAP work requirement for individuals not raising minor children found that more than 32 percent of the individuals who were subject to the requirement reported having a physical or behavioral health limitation that likely should have exempted them from the requirement.[18] Similarly, the evidence from TANF shows that families sanctioned due to noncompliance with work requirements were more likely than other families receiving TANF to have barriers that kept them from working, including having a child with a chronic illness or disability. Some studies have also found that health challenges such as substance use disorders and barriers such as experiencing domestic violence were more common among TANF enrollees who were sanctioned.[19]

As these studies show, state agencies administering work requirements in SNAP and TANF have struggled to appropriately exempt vulnerable individuals, even though SNAP and especially TANF eligibility workers often have substantial interactions with participants, including face-to-face or phone interviews. The results would likely be still more problematic in Medicaid, which has a streamlined eligibility determination process that relies heavily on online applications and electronic data verification; states are not permitted to require an interview, and few applicants apply in person. As a result, it would be nearly impossible for Medicaid agencies to accurately screen beneficiaries for exemptions and explain complex program requirements without significant additional resources and staff. If states fail to commit significant new resources for these purposes, as will likely be the case in many states, substantial numbers of errors could occur that adversely affect eligible individuals’ health coverage.[20]

In TANF, work requirements and sanctions have led to large declines in the number of families receiving basic assistance. States have a financial incentive to reduce TANF caseloads because doing so frees up funds they can use for other purposes. Similarly, states that want to reduce their spending on Medicaid could use work requirements and sanctions to shrink Medicaid enrollment. The more burdensome and unrealistic a state’s work requirements are, the less assistance that the state provides in helping individuals comply, the harder a state makes it for people to qualify for exemptions, and the more complicated a state’s paperwork requirements, the greater the number of people who will lose coverage — and the greater the Medicaid savings will be. (These savings, however, could be partially offset by higher uncompensated care costs, some of which will show up elsewhere in state budgets.)

Beyond harming people who are working or cannot work, work requirements are unlikely to increase employment among people who are looking for work or need additional services to be able to work. Instead, work requirements are likely to impede employment for some enrollees.

Employment increases for those subject to work requirements are generally modest and fade over time. [21] A RAND Corporation report synthesizing the evaluations of 13 programs imposing work requirements in TANF found that employment rose somewhat in the first two years, but these gains then faded. Moreover, in most of these programs, the impact of work requirements was modest even in the early years, in part because work was far more common among recipients than is generally understood.[22] Over a five-year period, evaluations consistently show that the vast majority of TANF recipients worked, irrespective of whether they were subject to work requirements.[23]

Moreover, stable employment proved the exception, not the norm, among those subject to work requirements.[24] Most TANF recipients would like to work and do look for employment, but the job market — and the challenges that many of these parents face — mean that they often have periods of unemployment. A study of a program designed to serve TANF parents with significant work barriers such as mental and physical conditions found that the vast majority of those subject to work requirements never found work. Many were sanctioned for noncompliance and ended up with neither TANF benefits nor income from work.[25]

To truly move individuals into stable long-term employment, programs need to invest in increasing the education and skills of participants, which TANF generally has not done — and which Medicaid-related work programs are similarly unlikely to do. This is especially true given that CMS has said that states may not use federal Medicaid funds for this purpose, even in states imposing work requirements on Medicaid enrollees.

Adult Medicaid enrollees already have a strong incentive to work: unless they work, they can usually obtain little assistance beyond health care, and they are typically very poor. Among non-working Michigan Medicaid expansion enrollees, for example, more than three-quarters have incomes below 35 percent of the poverty level.[26] The safety net provides no basic cash assistance to adults without serious disabilities who aren’t raising minor children, and for poor families with children, TANF has extremely low benefits and reaches just 23 such families for every 100 families with children in poverty. And SNAP benefits for most non-disabled, non-elderly adults not raising children are limited to three months in a 36-month period unless the individual is working or in job training at least 20 hours per week.

Rather than lack of motivation, Medicaid enrollees who seemingly could work but aren’t working often face serious barriers to employment, including low skills, criminal records, and lack of access to transportation, child care, and other needed work supports.

As discussed above, employment programs in TANF have shown disappointing results, even though participants have case managers who often meet with them and give at least a cursory look at their work histories and employment barriers. These programs also provide some, though often inadequate, resources for supportive services that can be essential for a beneficiary to work, such as transportation assistance or child care.

In contrast, state Medicaid programs do not provide these services or resources. And as noted, CMS’ guidance says states need not offer any work supports such as job training, transportation, or child care as a condition of implementing work requirements and may not use federal Medicaid funds for services. (CMS didn’t approve Indiana’s request to use a modest amount of Medicaid funding for this purpose.)

Nor can states rely on their existing TANF and SNAP employment programs to expand substantially to serve Medicaid applicants and beneficiaries. SNAP Employment and Training programs already struggle with limited resources and a shortage of work program slots for current SNAP participants. TANF funds can only be spent on families with children, and few states have funds in reserve that they have not already allocated to other state priorities, such as child welfare services and child care.

Indeed, Kentucky’s reliance on adult enrollees to find work or job training largely on their own — and its heavy emphasis on enrollees, themselves, finding volunteer positions as a way to meet the requirement, rather than the state establishing employment programs — points to the no-investment strategy underlying Kentucky’s and many other states’ proposals.

Another reason work requirements will likely be even less successful at promoting work in Medicaid than in other programs is that health care is itself a critical work support. As noted above, among non-working adults gaining coverage through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan, majorities said having health care made it easier to look for work; among working adults, majorities said coverage made it easier to work or made them better at their jobs. [27]

That’s not surprising, given the relationships between health care, health, and employment. As noted above, low-income adult Medicaid enrollees have high rates of chronic conditions and mental illness. When conditions like diabetes, heart disease, or depression are treated and controlled, individuals with these conditions may be able to hold a steady job. For example, a long-term randomized trial found that providing older adults with regular care for heart disease increased their earnings, likely by reducing their time out of work due to illness.[28] In contrast, if chronic conditions are untreated, or if they worsen in spite of treatment, work may become impossible. This means that work requirements can create a vicious cycle in which health setbacks lead to job loss, which in turn leads to loss of access to treatment, making it difficult or impossible to return to health and regain employment. Similarly, loss of coverage due to failure to document sufficient hours of work may lead to deteriorating health, causing job loss.

In addition, many low-income adults have undiagnosed physical or mental health conditions and receive treatment only after gaining coverage. Among Ohio Medicaid expansion enrollees, 27 percent were newly diagnosed with one or more serious physical health conditions after gaining coverage, with many then starting treatment.[29] Had they been forced instead to quickly find employment or participate in work activities in order to maintain their Medicaid coverage, some never would have gained access to treatment, making it less likely they would ever become consistently employed.

Reviewing the available evidence on health coverage, work, and health outcomes, Kaiser Family Foundation researchers conclude, “access to affordable health insurance and care, which may help people maintain or manage their health, promotes individuals’ ability to obtain and maintain employment.” Conversely, research shows that unmet need for health care, especially mental health or substance use treatment impedes employment.[30]

States requesting waivers to impose a Medicaid work requirement acknowledge that some enrollees will lose health coverage as a result. For example, Wisconsin projects that 27 percent of childless adult Medicaid enrollees with no income would lose coverage under the state’s work requirement proposal.[31] And the true coverage losses would likely be even larger, since the state’s estimate likely does not include those who meet the work requirements but lose coverage due to the burdens of documentation or administrative errors. Similarly, Kentucky projects that 15 percent of all adult Medicaid enrollees will ultimately lose coverage under its waiver, which includes a work requirement along with other burdensome changes.[32] These coverage losses will mean less access to care, less financial security, and worse health outcomes.

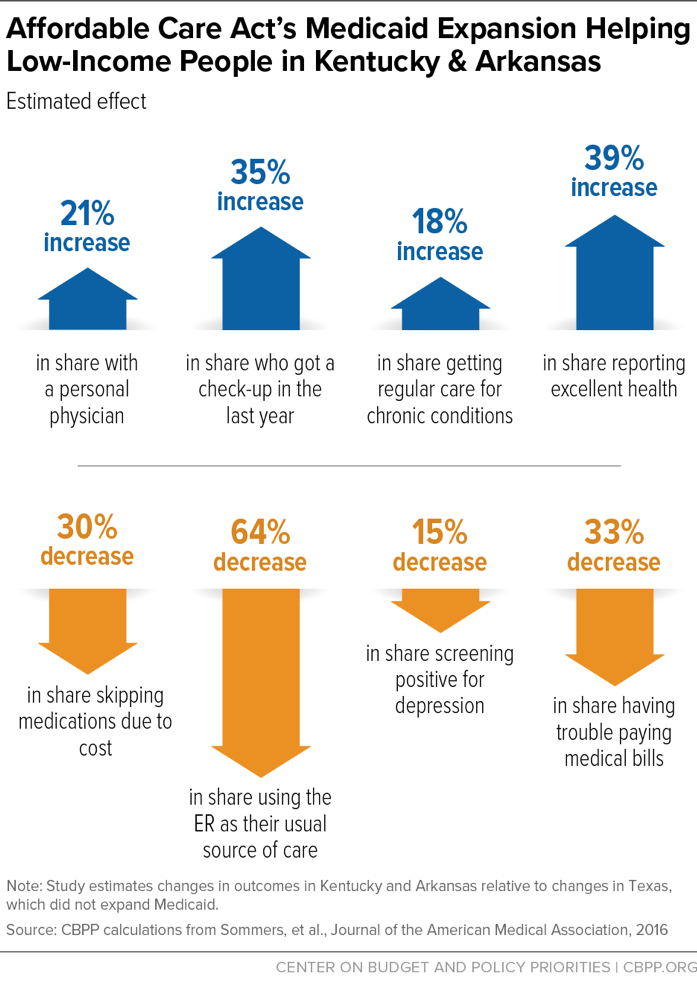

Gaining Medicaid coverage greatly improves access to care. (See Figure 3.) Studies find that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion resulted in increases in the share of people with a personal physician, the share getting check-ups, and the share getting recommended preventive care such as cholesterol and cancer screenings, along with decreases in the share of people delaying care due to costs, skipping medications due to costs, or relying on the emergency room for care.[33] The earlier Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, in which some low-income adults were randomly selected by lottery to receive Medicaid coverage, similarly found that gaining coverage led to increases in the share of adults with a usual source of care, receiving recommended preventive care, and reporting that they received all needed care.[34]

Improvements in access to care were especially important for certain groups. Among low-income adults with chronic conditions in Kentucky and Arkansas, the Medicaid expansion led to an 18 percent increase in the share receiving regular care for those conditions, compared to low-income adults in Texas, which did not expand Medicaid. Medicaid expansion also led to large increases in access to medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.[35]

Medicaid also improves financial security. People who gained coverage due to the Medicaid expansion are more likely to be financially secure than those who remained uninsured[36] and far less likely to have trouble paying medical bills.[37] Medicaid expansion led to reductions in medical debt, reductions in delinquencies, improvements in credit scores, and improved access to credit.[38]

There is also growing evidence that the improvements in access to care due to the ACA’s Medicaid expansion are translating into improvements in health. Studies have found improvements in self-reported overall health, reductions in the share of low-income adults screening positive for depression, and improvements in the quality of care received for surgical conditions.[39]

Studies of pre-ACA Medicaid expansions, which can look at outcomes over a longer period of time, also have found that these coverage expansions reduced premature deaths.[40]

Medicaid work requirements are ill-conceived: if imposed in all states currently seeking them, they would create new barriers to coverage for millions of low-income adults in an attempt to increase employment among a small minority of that group. They also are likely to be ineffective, and potentially counterproductive, on their own terms: evidence from other programs indicates that work requirements do not produce significant and sustained employment gains. And taking away people’s health coverage will likely impede employment for many.

More important, the evidence indicates that these policies will lead many people to lose or experience interruptions in coverage. As a result, far from promoting better health outcomes, they will lead to reduced access to care, disruptions in care for many people with serious health care needs, and, as a result, worse health.