The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the nation’s largest anti-hunger program, helps more than 40 million people put food on the table each month. While two-thirds of participants are children, adults over age 60, and people with disabilities, who are not expected to work, SNAP also plays an important role in supplementing workers’ low or fluctuating wages or helping them during periods of unemployment. As policymakers look toward the reauthorization of SNAP in the next farm bill, they should preserve the program’s vital role for workers and their families and reject proposals that would weaken SNAP benefits as participants cope with the realities of the low-wage labor market.

Many workers and their families participate in SNAP while they are working or are looking for work. SNAP helps workers by supplementing low or fluctuating earnings or supporting them temporarily while they are between jobs. SNAP provides assistance during short bouts of unemployment and income loss, but it also helps those with persistently low earnings, including those who have long-term barriers to employment and may need assistance in affording groceries over longer periods of time.

Adults who receive SNAP often work in occupations and industries with low pay or unstable hours that cause income volatility, such as important frontline service or sales roles like cashiers, cooks, or home health aides. Many of these jobs often lack benefits such as paid family leave — or even paid sick days — which means that a worker’s own illness or an illness in the family can lead to job loss.

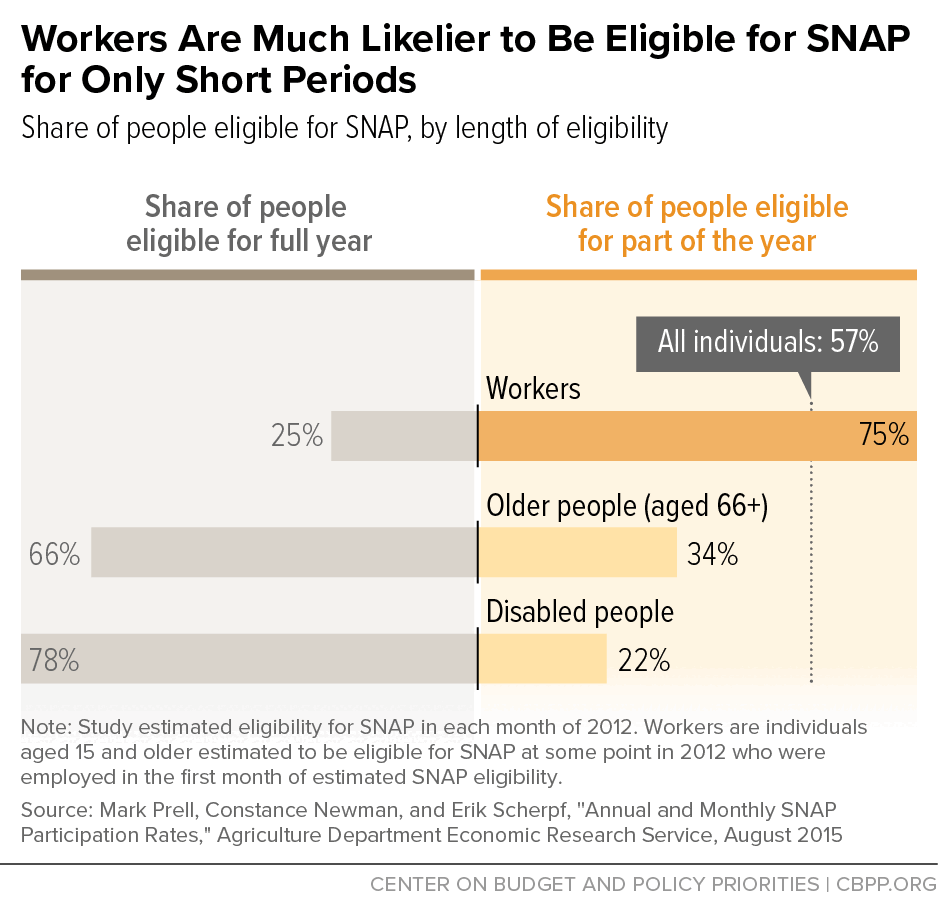

Many working-age adults participate in SNAP for part of the year and stop participating when they are earning more. Three-quarters of workers with low incomes who were eligible for SNAP at some time during the year were eligible for only part of the year, an Agriculture Department (USDA) study found.

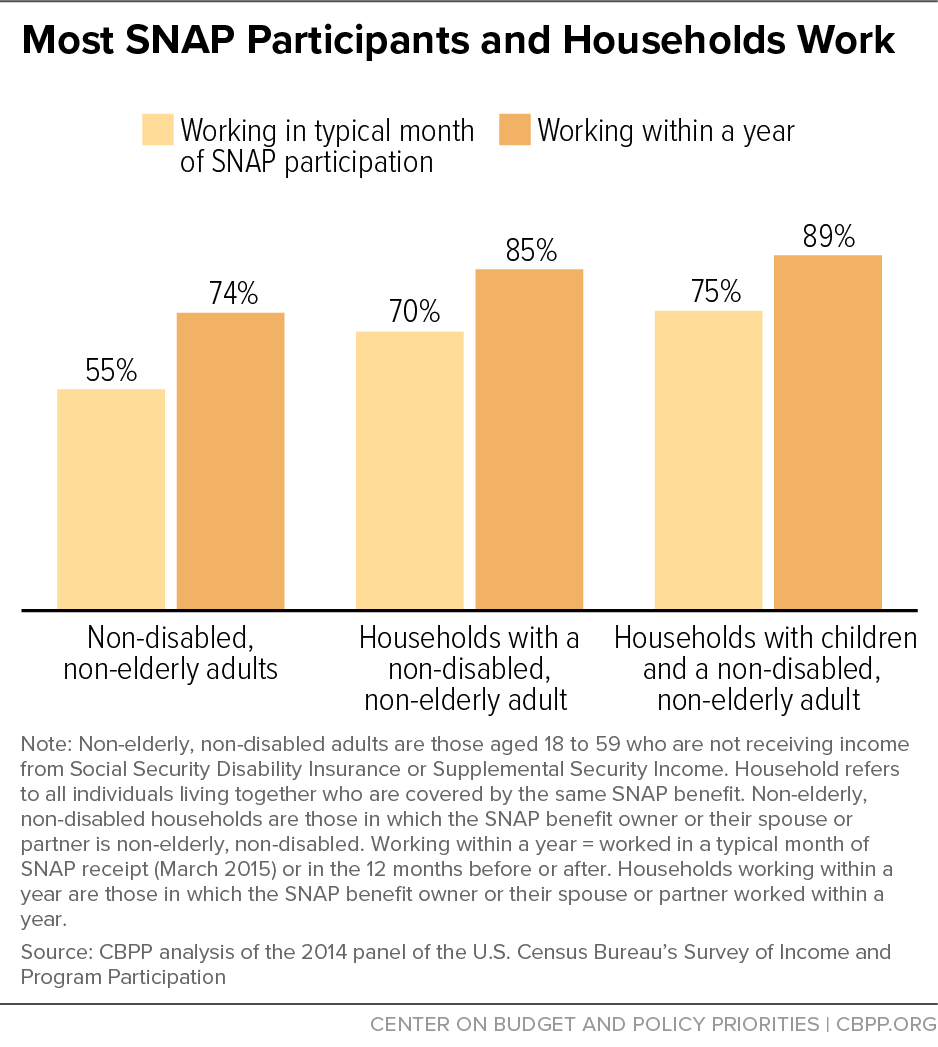

Most SNAP participants who can work do so. Over half of working-age, non-disabled people who participated in SNAP in a typical month in 2015 were working in that month, based on U.S. Census Bureau data. Further, 74 percent worked in the 12 months before or after that month.

Rates were even higher when including work among other household members: 89 percent of households with children and a working-age, non-disabled adult included at least one member who worked in this 25-month period. Many SNAP participants who did not work over the 25-month period reported caregiving responsibilities or faced barriers to work, including an injury or health condition.

More recent annual Census data also show that most SNAP households who are able to work do work. Among households with working-age adults who don’t live with minor children, did not receive disability benefits, and reported receiving SNAP at some point in 2021, 86 percent had earnings during the year, based on our analysis of 2021 American Community Survey data.

SNAP’s structure supports workers in a volatile labor market. SNAP benefits phase out slowly as earnings rise and include a 20 percent deduction for earned income to reflect the cost of work-related expenses and to further assist workers. As a result, SNAP benefits fall by only 24 to 36 cents for each additional dollar of earnings for most households. SNAP provides crucial support for unemployed workers because they can apply when their incomes drop and receive benefits quickly and on a monthly basis, unlike some other programs that have waiting lists or provide benefits annually. Benefits are quite modest. If a household has no income, benefits will average only about $8-$9 per person per day.

But the program includes an ineffective policy that takes away food assistance from certain adults aged 18 through 54 who do not have minor children in the home, do not receive disability benefits, and can’t meet a 20-hour-a-week work-reporting requirement. These individuals will lose their food assistance benefits after three months if they cannot show that they are working or engaged in a qualifying work program for 20 hours or more a week or secure an exemption. Numerous studies have shown that this harsh policy does not increase employment or earnings — it just cuts people off from the food assistance they need to buy groceries. Policymakers must reject proposals to broaden these requirements in the forthcoming farm bill. In fact, they should seek to eliminate this failed policy altogether.

SNAP, the nation’s largest anti-hunger program, provides over 40 million low-income people with the means to purchase food in a typical month. SNAP is broadly available to people who meet the program’s eligibility requirements and serves a large cross-section of people with the lowest incomes.

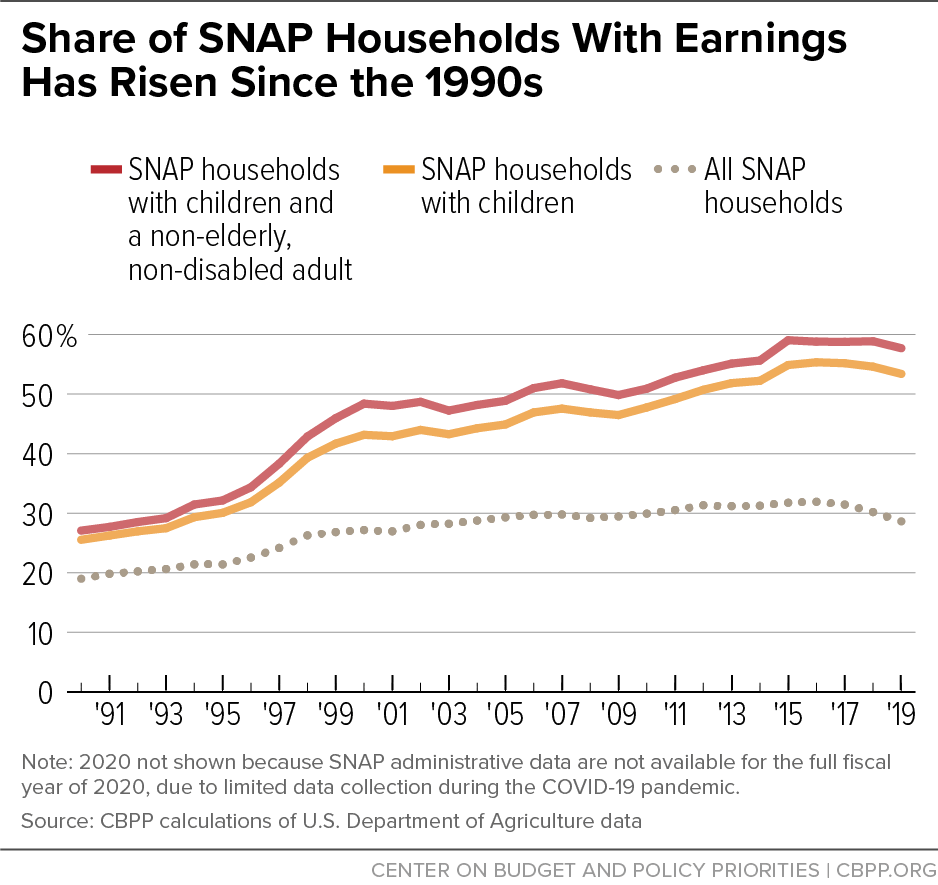

The share of SNAP households with earnings has grown since the 1990s. The share of all households with earnings in an average month while participating in SNAP rose from 19 percent in 1990 to 28 percent in 2020. (See Figure 1.) USDA data from program participants show that among households with children and a non-elderly, non-disabled adult, about 60 percent have earnings while participating in SNAP.

The share of SNAP households with earnings has declined slightly in recent years. This may be due, in part, to a greater share of participants who are older, retired adults, mirroring an overall aging trend in the U.S. population.[1] The share of SNAP participants aged 60 or older doubled between 2010 and 2020, rising from 8 percent to about 16 percent of participants.[2]

More than two-thirds of SNAP participants at a point in time are not expected to work, primarily because they are children, older adults, or disabled people. Most SNAP participants who can work do so. Many workers participate in SNAP for part of the year, while they are between jobs or during periods when their earnings or their work hours are low, and they stop participating when they are earning more.

As a result, a snapshot of work among SNAP participants undercounts workers, as many workers only participate in SNAP when they are not working, and workers may cycle in and out of eligibility. The share of SNAP households with earnings in an average month is lower than the share of households who reported receiving SNAP in a given year and also had earnings during the year.

Census data show that among households who reported receiving SNAP at any point during 2021 with at least one working-age (18- to 59-year-old), non-disabled adult, 86 percent had earnings during the year.[3] Three-quarters of workers with low incomes who were eligible for SNAP at some time during the year were eligible for only part of the year, a USDA study found. (See Figure 2.) In contrast, the majority of eligible people who had more stable and often fixed incomes, such as older adults and people with disabilities, were eligible for the full year.[4]

Among non-disabled, non-elderly adults participating in SNAP in a typical month in 2015, over half worked in that month, according to a CBPP analysis of employment and SNAP participation based on U.S. Census Bureau longitudinal data (which tracks survey respondents over time).[5] Further, 74 percent worked in the 12 months before or after that month. Rates were even higher when including work among other household members: 89 percent of households with children and a non-disabled adult included at least one member who worked in this 25-month period.[6] (See Figure 3.)

Joblessness is often temporary, as shown by the higher rate of work among SNAP participants when measured over a longer period rather than a single month snapshot. Examining work status among participants at a given point in time (for example, the USDA’s point-in-time estimates) substantially overstates their joblessness because these estimates do not capture SNAP participation patterns or work patterns over time. (Other reasons for discrepancies between data sources include who is sampled and how well earnings are captured.)[7]

The animation below in Figure 3A shows a stylized example of people who participate in SNAP as they move in and out of work. As described above, looking at any given month doesn’t tell the whole story, because work is often unstable, with SNAP participants moving in and out of work and often using SNAP as a short-term support. Most participants only receive SNAP for part of a given time period and move in and out of SNAP participation over time.

Figure 3A

In a typical month of SNAP participation, about half of non-disabled adults under 60 are working.

But many SNAP participants move in and out of work frequently.

Most will have worked at some point over the course of a year.

Note: Individual dots are for illustrative purposes and do not correspond to real survey participants.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities |

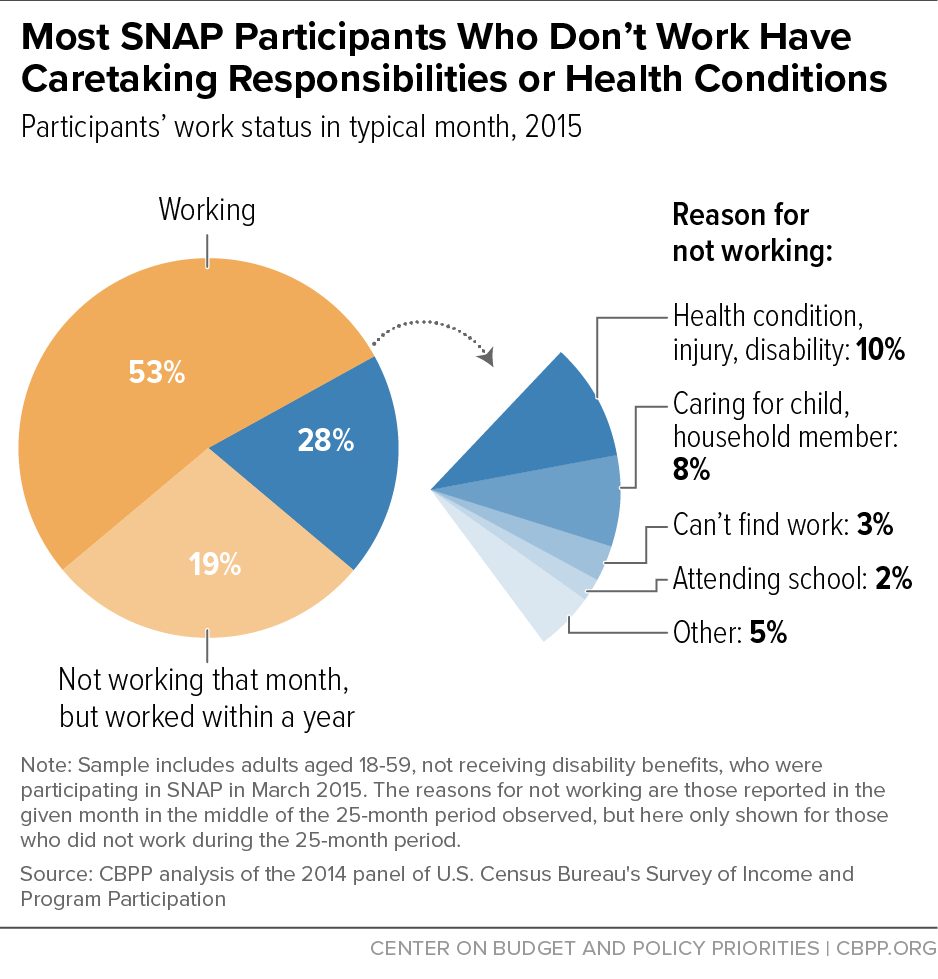

cbpp.orgWork is substantial for employed participants, though it may not always occur in the months when the individuals participate in SNAP. When participants work, they typically work at least half time and usually full time. Those who did not work over the 25-month period studied most frequently reported they had health issues that affected their ability to work, had caregiving responsibilities, couldn’t find work, or were attending school. (See Figure 4.) These adults were also more likely than those who worked to lack a high school diploma or to report a disability or health condition for which they did not receive disability assistance, both of which may present barriers to work.[8]

SNAP provides crucial support for workers because they can apply when their incomes drop and receive benefits quickly and on a monthly basis — unlike other programs, where applicants may face a waiting list for benefits. SNAP must provide benefits to eligible applicants within 30 days, and they often receive them much sooner. SNAP benefits average only $6 per person per day. If a household has no income, its benefits average only about $8-9 a day.

SNAP benefits are designed to support workers. The SNAP benefit formula bases benefits on a household’s income and expenses, phases out benefits slowly as earnings rise, and includes a 20 percent deduction for earned income to reflect the cost of work-related expenses and to further assist workers. As a result, for most households, SNAP benefits fall by only 24 to 36 cents for each additional dollar of earnings. (While SNAP falls as earnings rise, the Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC] increases as earnings rise from very low levels, particularly for families with children, offering a counterbalance to declining SNAP.)

In addition, workers whose pay fluctuates can qualify for higher benefits when their earnings decline, which can help smooth out income for workers with variable hours and pay.[9] SNAP also serves as an important complement to the EITC and Child Tax Credit, which provide crucial income for low-income families with children but in the form of annual tax credits, while SNAP can support families on a monthly basis when needed.[10]

As this paper describes, SNAP serves as an important support for many working-age individuals and their families. While many are experiencing temporary unemployment, SNAP also helps those with persistently low earnings, including those who have long-term barriers to employment, who may need assistance in affording groceries over longer periods of time. An ineffective policy that takes food assistance away from many people who can’t meet a work-reporting requirement ignores these realities.

SNAP’s policy that takes food assistance away from certain people who can’t meet a work-reporting requirement has returned this summer in many parts of the U.S., after being paused during the COVID-19 public health emergency. This will mean that people who are between jobs, who have health conditions or caregiving responsibilities that impede work at least temporarily, whose work hours fluctuate, or who face challenges navigating the red tape of the reporting and exemption systems will be at risk of losing the food assistance they need to buy groceries.

Adults aged 18-49 without minor children in the home and who do not receive disability-related benefits and are therefore subject to the work-reporting requirement must show that they are working or engaged in a qualifying work program for 20 hours or more a week or secure an exemption. If they can’t, or they do not live in an area where this requirement is waived, they will lose their food assistance benefits after just three months. As a result, about 500,000 — and possibly closer to 1 million — of the nation’s lowest-income adults will be cut off from SNAP beginning in October 2023.[11]

The recent debt ceiling agreement expands the existing, failed SNAP work-reporting requirements to older adults aged 50-54, while exempting veterans, people experiencing homelessness, and former foster youth from the policy.[12] The policy holds little potential to increase work among this population and carries a high risk of increasing hardship among workers.

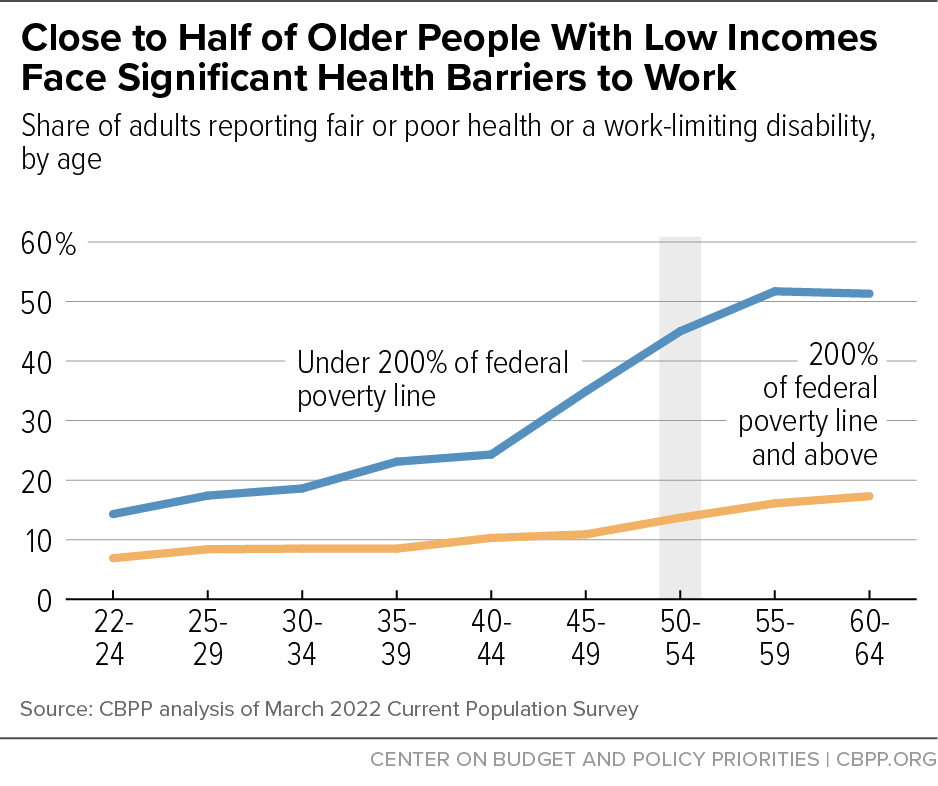

The older adults who would be newly subject to this work-reporting requirement may be particularly vulnerable to losing benefits due to age-related employment challenges. The prevalence of health conditions rapidly increases for low-income adults starting in their 40s, and nearly half of low-income adults aged 50-54 report a health barrier to work. (See Figure 5.) The share of older adults with incomes below twice the poverty line who have health conditions is three times higher than the share of those with incomes above this level.

SNAP’s existing work-reporting requirement has proven to be a failure. It is based on false assumptions rooted in unfounded stereotypes around race, gender, disability status, and class. And strong evidence shows that it does not increase employment or earnings but does cause many people to lose food assistance.[13] Recent studies have found that the time limit cut SNAP participation among those subject to it by as much as 53 percent, with no evidence of improvement in employment.[14]

Those who will be newly at risk of losing food assistance have very low incomes — typically well below the poverty line — and would be pushed even deeper into poverty if they lost SNAP. The new exemptions are positive, but improvements for some do not justify expanding a failed policy to others.

As Congress prepares to reauthorize SNAP in the pending farm bill, proposals put forward by some House Republicans would further harm SNAP participants by making already harsh work requirements even stricter, putting even more people — including children — at risk of losing at least some of their food benefits. Policymakers should recognize the realities of how SNAP serves workers and their families and reject proposals to make work requirements stricter. Indeed, given the strong evidence that the policy is a failure, policymakers should be working to eliminate this failed policy.