The new proposal from Senators Mitt Romney, Richard Burr, and Steve Daines to expand the Child Tax Credit is a welcome development, showing that there is bipartisan support for strengthening this vital support for families with low incomes, which should be a top priority in any tax legislation later this year. At the same time, the proposal has significant weaknesses. Most notably, while it would increase the credit for most children in the lowest-income families, children in families without earnings in a year would get no credit at all, while millions of other children in families with very low earnings would get only a partial credit. And, low- and moderate-income families would have to pay for much of its cost through a large cut in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and other offsets, leaving millions of children worse off than they would be without the Romney plan. Nevertheless, the proposal includes some important improvements to the Child Tax Credit compared to current law and may help create an opening for enacting a meaningful expansion this year.

The 2021 American Rescue Plan expanded the Child Tax Credit temporarily, including delivering the same credit amount to children in low-income families as in higher-income ones for the first time. Prior to the Rescue Plan, roughly 27 million children received less than the full credit or no credit at all because their families earned too little; they included roughly half of all Black children, half of Latino children, roughly one-fifth of white children, one-fifth of Asian children, and roughly half of children living in rural areas. The expansion cut child poverty dramatically: measured by monthly income, child poverty in December 2021 was nearly 30 percent lower than it would have been without the expansion. But when it expired in December, monthly payments were taken away from millions of low-income families who had used the income boost to meet the rising costs of food, energy, and other basics.

The Romney proposal’s Child Tax Credit expansion falls short of the Rescue Plan expansion —and a prior version of Senator Romney’s Family Security Act released last year — by not making the full credit available to families with little or no income. Instead, it includes an earnings requirement and phases in the credit as earnings rise; families would have to earn $10,000 to qualify for the full credit (which the proposal would increase from $2,000 per child to $4,200 for children under age 6 and $3,000 for children aged 6-17) for each of their children. This is a serious flaw because the children denied the full credit are the very children who stand to benefit the most, in both the short and long term, from the additional income it could provide.

That said, the Romney plan (the Family Security Act 2.0) does include three important improvements over the current Child Tax Credit design. First, and most importantly, it phases in the credit much faster as a family’s earnings rise and does so for each child in a family simultaneously, or on a “per-child” basis. Under current law, the credit phases in at a slow 15 percent rate for the total credit, regardless of whether a family has one, two, or more children. Second, the plan phases in the credit beginning with a family’s first dollar of earnings; under current law, the first $2,500 of earnings does not count toward eligibility for the credit. Third, the plan eliminates the cap (currently $1,500 per child, established in the 2017 tax law) on the credit that a family can receive as a refund.

The Romney proposal would undo a substantial part of these improvements, however, by requiring families with low and moderate incomes to pay for more than half of the cost of expanding the credit. While the plan’s changes to the Child Tax Credit would lift an estimated 2.6 million children above the poverty line, two of its offsets, discussed below, would push roughly half of these children back into poverty. As a result, the combination of the Child Tax Credit changes and those two offsets would lift 1.3 million fewer children above the poverty line than the Child Tax Credit changes alone would.

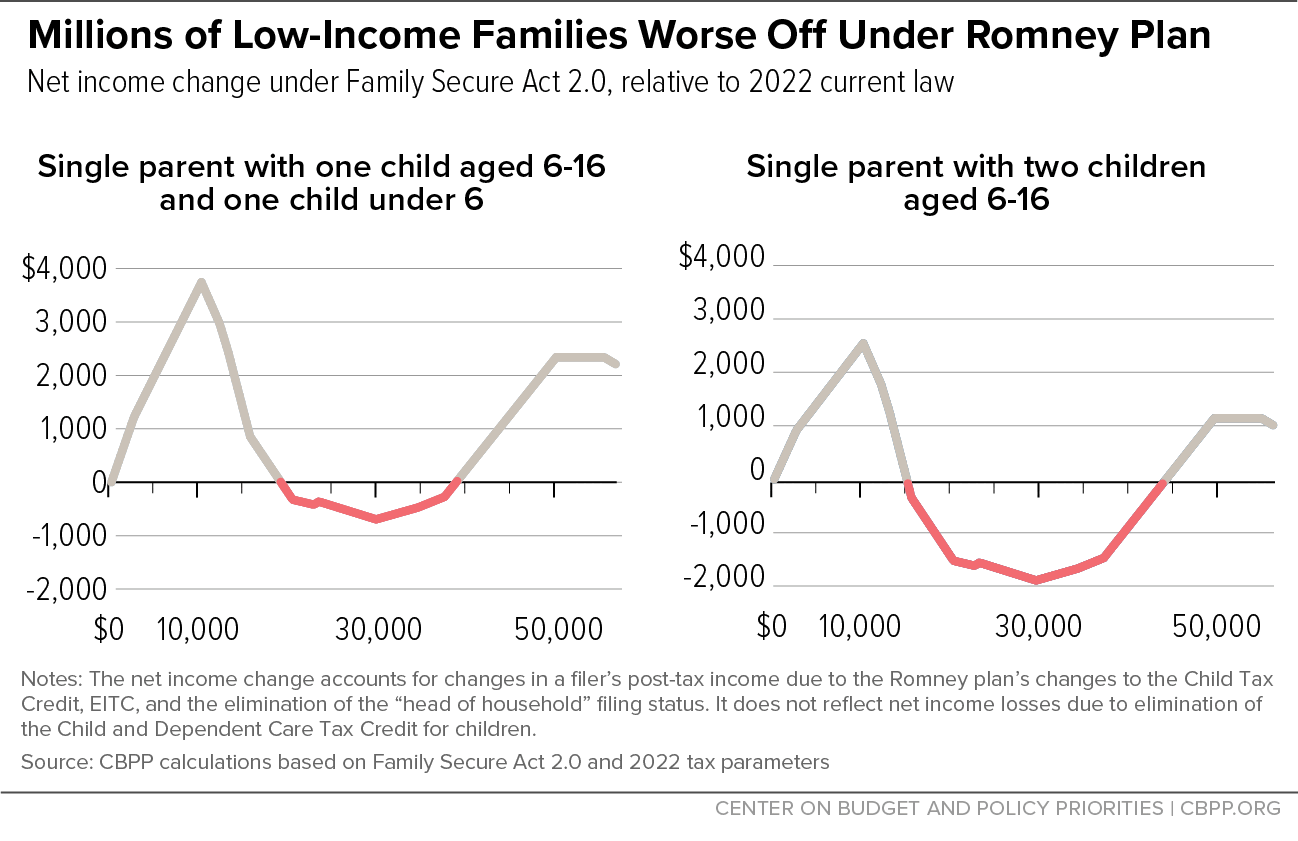

The Romney plan would dramatically cut the EITC, a credit that provides an income boost for workers with low and moderate incomes, and eliminate the “head of household” tax filing status, which millions of single parents who work at low-paying jobs use when they file their income tax returns. The cuts are so deep that about 7 million families making less than $50,000, with about 10 million children, would end up worse off under the Romney plan than under current law, with the typical (median) loss exceeding $800 per family. [1] These low- and moderate-income families — many of whom are single mothers working as home health aides, child care providers, or in food preparation jobs as cooks, servers, or cashiers — are the very families whom any Child Tax Credit expansion should target for the largest gains.

For example, consider a single mother who has a toddler and a daughter in second grade and works as a home health aide, making $25,000 a year. Her family’s Child Tax Credit would grow by $3,640 under the Romney plan, but they would lose $4,105 from the EITC cuts and the elimination of the head of household filing status, for a net income loss of $465. If both children were age 6 or older, the net income loss would be even larger: $1,665.

The EITC cuts and the elimination of the head of household filing status have an especially large impact on single-parent families, since the EITC cut for single-parent families is $1,000 larger than the cut for married families, and married families are unaffected by the elimination of the head of household filing status. The EITC cuts alone pay for roughly half of the total cost of the Child Tax Credit expansion; the two cuts together offset two-thirds of the cost.

At a time when some of the wealthiest people in the country benefit from tax preferences that enable them to pay little if any of their income in income tax, policymakers have no business asking people who work hard for low pay to foot most of the bill for a proposal that provides the full Child Tax Credit increase to married-couple families with incomes up to $400,000 and a partial increase for families even higher on the income scale. Congress should reject these offsets in bipartisan negotiations over expanding the Child Tax Credit.

The top priority in any expansion of the Child Tax Credit should be making the full credit available to all children in families with low incomes, as the reconciliation bill the House passed last year would do on a permanent basis. Short of that, Senator Romney’s proposed changes to the Child Tax Credit — but not his proposed offsets — would improve it compared to current law and, importantly, help create an opening for bipartisan action later this year.

The Romney proposal[2] would increase the maximum Child Tax Credit from $2,000 per child to $4,200 for children under age 6 and to $3,000 for children aged 6-17. (Children aged 17 would once again be eligible for the credit, as they were in 2021 due to the Rescue Plan.) In addition, parents could qualify for a $2,800 credit during pregnancy within four months of their due date, with the option to receive four $700 monthly payments.

To qualify for the maximum credit for each child in the family, families would need to have earned at least $10,000 in the prior year; this $10,000 threshold would be indexed to inflation. Families with earnings below $10,000 would receive a proportional credit. For example, a family earning $5,000 would receive 50 percent of the maximum credit for each child. The maximum credit would go to couples making up to $400,000 and single parents making up to $200,000, as under current law (which reflects the 2017 tax law’s expansion of the credit up the income scale). The credit would be delivered monthly — or annually, if a family prefers — by the Social Security Administration.

The $10,000 earnings requirement to receive the full credit would apply to all families, including parents with babies and young children, retired grandparents caring for their grandchildren, and parents with disabilities that may limit their ability to work. It would also newly require caregivers not only to live with the child but also to have legal custody of the child, which is stricter than current law and may disqualify many grandparents or other relatives who care for children from claiming the credit. And it would impose a new restriction for families that include immigrants: under current law, children must have a Social Security number (SSN) to qualify for the Child Tax Credit, but the proposal would impose an additional requirement that a parent also have an SSN, denying the credit to children who are U.S. citizens if their parents lack an SSN.

The major flaw in the current Child Tax Credit has been its denial of some or all of the credit to children in families with little or no income, even though they stand to benefit the most from the extra income. Prior to the Rescue Plan’s temporary expansion of the credit, roughly 27 million children received less than the full credit or no credit at all because their families earned too little. They included roughly half of all Black children, half of Latino children, roughly one-fifth of white children, one-fifth of Asian children, and roughly half of children living in rural areas.[3]

The Rescue Plan addressed this fundamental design flaw for 2021 by making the full credit available to children in families with low or no income, sometimes called making it “fully refundable.” This led to a sharp decline in child poverty, reducing child poverty by nearly 30 percent (measured by monthly income) in December 2021.[4]

The prior version of Senator Romney’s Family Security Act[5] adhered to the principle that children in families with low incomes should be eligible for the same maximum Child Tax Credit as children in families with higher incomes. Unfortunately, the new Romney proposal takes a step backward, requiring families to have at least $10,000 in earnings to receive the full credit. Had the new proposal maintained the full refundability principle of the prior proposal, its Child Tax Credit expansion would lift an additional 1.5 million children above the poverty line: 4.1 million versus 2.6 million.[6]

Denying the full credit to children based on their parents’ earnings would do virtually nothing to boost parental employment and would withhold help from the children who most need it, hurting their chances to improve their long-term health and educational outcomes and to increase their earnings as an adult:

- In more than 95 percent of families who benefit from making the credit fully refundable, the parent or other caretaker is working, between jobs, ill or disabled, elderly, or has a child under age 2.[7]

- Evidence from both the United States and Canada strongly indicates that giving the full credit to all children, including those whose families don’t have earnings in a year, won’t affect adults’ work participation to any large degree. Most estimates suggest around 99 percent of parents would continue to work under an expanded credit.[8]

- An earnings requirement hurts children whose parents are least able to meet basic needs, exposing these children to serious hardship.

- Research links additional income to better outcomes for children in families with low incomes. The added income could significantly improve their long-term health and how well they do in school, make it more likely they will finish high school and attend college, and boost their earnings as adults.[9]

The proposed earnings requirement is unfortunate, especially because it doesn’t include some exceptions that have been widely discussed. For example, it doesn’t exempt families with younger children (who often face more hurdles to working than families with older children and for whom child care is particularly expensive), children being cared for by grandparents or other relatives, or children whose parents have disabilities. And, it doesn’t allow parents who are temporarily out of work but who worked in prior years to claim the credit, just when their families need it the most.

If policymakers move toward a compromise on a Child Tax Credit expansion, the highest priority should be to make the credit fully refundable. But if that isn’t politically possible and an earnings requirement is included, important exemptions should be included as well. These issues are discussed in more detail below.

While the Romney plan would not provide the same Child Tax Credit to children in families with the lowest incomes as to those with higher incomes, it would, in addition to the positive step of providing the credit monthly, redesign and improve the rules for phasing in the credit for lower-income families as their incomes rise. This redesigned phase-in structure would make families with low incomes far better off than under current law. (As detailed below, however, the proposed cuts in the EITC and the elimination of the head of household status would claw back much or all of the gains for many families.)

The current-law credit’s phase-in structure has the following flaws:

- For low-income families, the credit phases in at a rate of 15 cents per dollar of earnings above $2,500 regardless of how many children they have. Put another way, the phase-in sets the amount the family receives in total, not the amount each child receives. So, for example, a family with $12,000 in income gets the same credit — $1,425 — regardless of whether they have one child or more than one. By contrast, middle- and higher-income families receive $2,000 per child.

- A family’s first $2,500 of earnings do not count toward calculating their credit. (This threshold for where the phase-in begins, first set at $10,000 in 2001, has been reduced over time on a bipartisan basis; the 2017 tax law cut it from $3,000 to $2,500 through 2025.)

- The 2017 tax law newly imposed a refundability cap on the credit, which limits the maximum credit for many low-income families below the maximum $2,000-per-child credit for families with higher incomes. The current refundability cap is $1,500 per child.

Because of these rules (especially the slow phase-in and lack of a per-child phase-in), a single parent with two children must earn at least $29,400 — and a married couple with two children must earn at least $35,900 — to receive the full $2,000-per-child credit for both children. These earnings levels are roughly twice what one parent working full-time at the minimum wage would earn. That is, under current law a parent with two children must earn at least twice the minimum wage to gain the same benefit from the Child Tax Credit that higher-income families receive.

The Romney plan would replace this flawed phase-in design with a significantly improved structure: families with one, two, or more children and with earnings of at least $10,000 (indexed for inflation) in the prior year would receive the full credit for each child, while families with earnings below $10,000 would receive a proportional credit. For example, a family earning $5,000 would receive 50 percent of the maximum credit for each child.

To see the impact of this change, consider a single mother with children ages 4 and 7 who works part time around her children’s schedule as a cashier in a convenience store, and makes $12,000. Under current law, her family receives a Child Tax Credit of $1,425 — effectively a partial credit for one child and no credit for the second child. Under the Romney plan’s phase-in structure, their credit would rise to $4,000, even without the proposal’s increase in the maximum credit. (Their credit would rise to $7,200 with the proposed increase in the credit amount.)

The Romney plan’s changes to the phase-in structure, combined with its increase in the maximum credit, extension of eligibility to 17-year-olds, and other changes, would lift a total of 2.6 million children above the poverty line and another 4 million children closer to the poverty line. However, the proposed offsets to pay for the Child Tax Credit expansion would reverse roughly half of this reduction in child poverty, as discussed below.

Plan Targets Low- and Moderate-Income Families to Largely Pay for Child Tax Credit Increase

The Romney proposal would make families with low and moderate incomes pay for a substantial portion of the cost of expanding the Child Tax Credit. Previous efforts by either Republicans or Democrats to expand the credit — in 2001, 2009, 2017, and 2021 — focused on boosting the incomes of families who work hard at low-paying jobs.[10] In stark contrast, the new Romney plan cuts the incomes of roughly 7 million families, with about 10 million children, who have incomes below $50,000, even though one would expect these families to be prime beneficiaries of a Child Tax Credit expansion. The typical (median) loss would exceed $800 per family.[11]

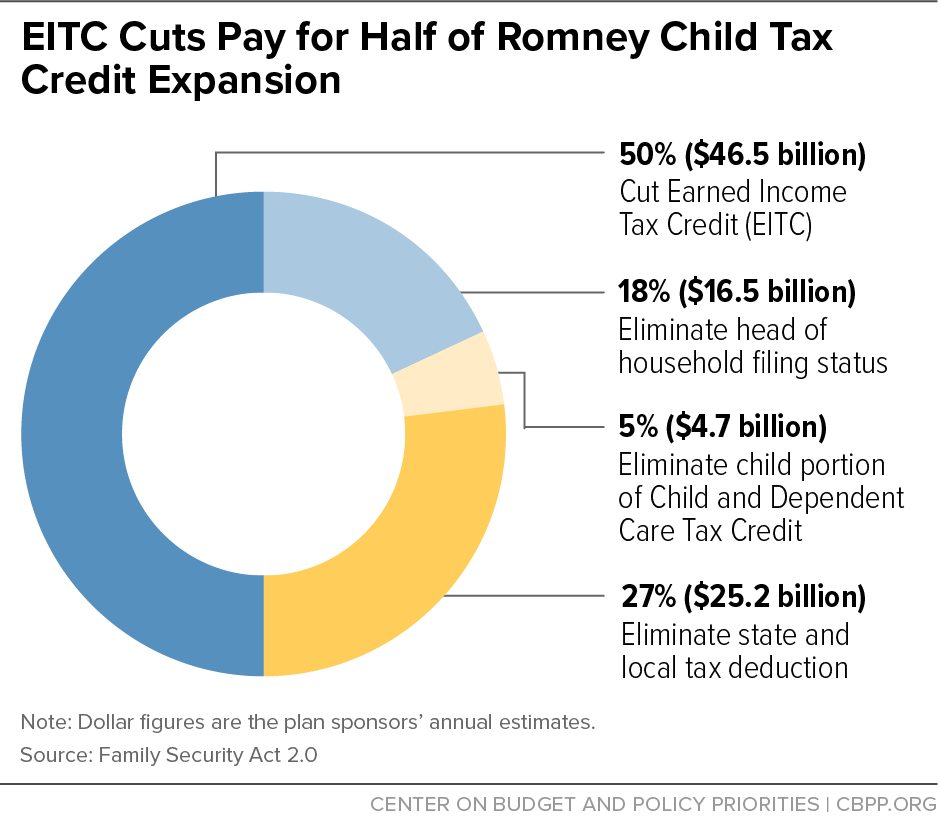

Deep cuts to the EITC would pay for fully half of the cost of the Romney proposal, according to Senator Romney’s figures. In addition, the Romney proposal would eliminate the head of household filing status, a change that on its own would make the tax code less progressive, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).[12] Together, these changes — which target single-parent families in particular, as discussed below — would offset two-thirds of the cost of the proposal, according to Romney. Eliminating the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit for children, which some families with lower and moderate incomes claim to help pay for child care (though its lack of refundability limits its use for this group), would also pay for a small part of the proposal. (See Figure 1.)

Because of these changes, parents working as home health aides, retail salespeople, cooks, cashiers, and child care workers would foot much of the bill for expanding the Child Tax Credit. One significant offset in the proposal that targets higher-income households is its elimination of the federal deduction for state and local taxes (SALT), but this would cover just 27 percent of the plan’s total cost, according to the Romney figures — only about half as much as the deep cuts to the EITC.

Targeting low- and moderate-income families, particularly single-parent families, for most of the offsets is particularly egregious given that the Romney proposal’s increase in the maximum Child Tax Credit would benefit families far up the income scale. Married couples with one younger and one older child, for example, would receive the full increase in the credit for incomes up to $400,000 and at least some increase for incomes up to about $540,000.[13]

| TABLE 1 |

| |

Romney EITC |

Current Law EITC |

Difference in EITC |

| Single parent with 1 child earning: |

| $15,000 |

$2,000 |

$3,733 |

-$1,733 |

| $25,000 |

$1,714 |

$2,955 |

-$1,241 |

| $35,000 |

$285 |

$1,357 |

-$1,072 |

| Single parent with 2 children earning: |

| $15,000 |

$2,000 |

$6,000 |

-$4,000 |

| $25,000 |

$1,714 |

$5,138 |

-$3,424 |

| $35,000 |

$285 |

$3,032 |

-$2,747 |

| Married parents with 1 child earning: |

| $15,000 |

$2,501 |

$3,733 |

-$1,232 |

| $25,000 |

$3,000 |

$3,733 |

-$733 |

| $35,000 |

$2,714 |

$2,336 |

+$378 |

| Married parents with 2 children earning: |

| $15,000 |

$2,501 |

$6,000 |

-$3,499 |

| $25,000 |

$3,000 |

$6,164 |

-$3,164 |

| $35,000 |

$2,714 |

$4,323 |

-$1,609 |

The EITC is a successful wage subsidy that phases in from the first dollar of earnings (at varying rates based on family size), plateaus at the maximum level, then phases out. The Romney plan would dramatically cut both the phase-in rate and the maximum EITC for single parents and married couples with children.[14] It would hit single parents especially hard by cutting the maximum EITC to $3,000 for married couples with children and $2,000 for single parents. (Currently, the maximum EITC ranges from $3,733 for families with one child to $6,935 for families with three or more children under current law, regardless of filing status.) For a single parent with two children, the credit would be fully phased out at an income of $37,000 under the Romney plan, compared to just under $50,000 under current law. Table 1 shows how deep the EITC cuts would be for various family types and incomes.[15]

Under current law, the standard deduction is $12,950 for single people without dependents and $25,900 for married couples; the standard deduction for heads of households (typically, single parents or other single people with dependents) is set between these two, at $19,400 in 2022.

The Romney plan’s elimination of the head of household filing status means single parents would claim the same standard deduction as single adults without children. That is, the threshold for when their earnings would be subject to income taxes would fall by $6,450 ($19,400 minus $12,950).

Single parents with incomes at or above $19,400 but not above the ceiling for the 10-percent income tax bracket for single filers ($23,225) would lose $645 (10 percent of $6,450). The income loss would be somewhat larger for single parents with incomes in the 12-percent bracket (that is, between $23,225 and $54,725) and somewhat smaller for single parents with incomes between $12,950 and $19,400.

Taken alone, the Romney plan’s Child Tax Credit changes would lift 2.6 million children above the poverty line. But its EITC and head of household offsets cut this figure roughly in half, to 1.3 million children.[16] Strikingly, that’s fewer than simply making the current $2,000-per-child credit fully refundable, which would lift 1.7 million children above the poverty line.

Moreover, due to the deep EITC cuts and elimination of the head of household filing status, about 10 million children in families with incomes below $50,000 would see their family’s income cut under the Romney plan, despite the increase in their Child Tax Credit.[17] The children who would be worse off under the Romney plan are disproportionately Black and Latino, largely because they are more likely than white children to live with single parents with low and moderate incomes.

For example, a single mother who has a daughter in fourth grade and a son in first grade and who makes $25,000 at a child care center would lose $1,665 under the Romney plan. Many single parents with incomes between roughly $16,000 and $40,000 would have their incomes cut by the plan. (See Figure 2.) Single parents in this income range, most of whom are single mothers, include many people who work hard for low pay in occupations that include home health aides, child care providers, and food preparation workers. These families should be among the prime beneficiaries of any Child Tax Credit expansion, not be made worse off.

To be sure, roughly 20 million children in families making less than $50,000 would be better off under the Romney plan than under current law. But there is no justification for making 10 million other children worse off while increasing the Child Tax Credit for households with incomes up to $400,000. A better designed plan, paid for by raising revenues on high-income households instead of cutting the EITC and standard deduction for single parents, would do more to reduce poverty among children and help families make ends meet.

Some proponents of tax changes that hurt single parents defend the changes as necessary to promote marriage. Sometimes two people who choose to marry pay more in taxes when married; sometimes they pay less. Research suggests, however, that such marriage incentives have at most modest effects on marriage decisions and that most people choose whether to marry for other reasons than tax incentives.[18] When studies find any effect of tax incentives on marriage, the effects are so limited in size that further lowering the after-tax income of low-income single-parent families would likely push many times more families into poverty (through direct income loss) than it would remove from poverty (through increased marriage). Moreover, policymakers on a bipartisan basis have addressed concerns about “marriage penalties” in the EITC without hurting single mothers who work for low wages, by increasing the income level at which the EITC phases out for married couples. They did so, for instance, in 2001 under President Bush and again in 2009 under President Obama, a change they made permanent in 2015 on a bipartisan basis.[19]

While policymakers should reject outright the Romney plan’s offsets targeting families with low and moderate incomes, its core changes in the Child Tax Credit — specifically, the faster phase-in and especially the per-child structure — would constitute advances over current law. But further improvements would strengthen the design. The main flaw of the plan’s redesigned Child Tax Credit is that the full credit would not be available to children in families with the lowest incomes. Thus, the single best improvement to this design would be to make the credit fully refundable, as the prior Romney plan did.

The lack of full refundability is particularly inappropriate for certain groups of people. These groups, which should be excluded from an earnings requirement if the credit is not made fully refundable, include:

- Parents of young children. Parents tend to work less when their children are young because they take time off to care for them. This means their incomes drop at the very time when, research tells us, economic stability is extremely important for children’s healthy development. The Romney plan already includes a larger Child Tax Credit for young children (under age 6) than for older ones, likely for this very reason. Policymakers should make the credit fully refundable for the children in this subgroup.

- Caregivers who are older, disabled, or receiving Social Security. Children should not be excluded from the Child Tax Credit simply because they live with parents or other relatives who are past the age at which many people work or are able to work, who have a work-limiting disability, or who receive Social Security survivors benefits. Policymakers should make the credit fully refundable for tax filers who are age 60 or older and those who receive Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, or veterans’ disability benefits.

- Other relatives caring for children. Relatives who step in to help care for children, such as grandparents or aunts and uncles, should not be subject to an earnings requirement. Providing such care is itself such a service — to the larger society as well as the child — that it alone should be qualification for the full Child Tax Credit. Moreover, some of these adults never intended to raise children and may not be working for many reasons.

- Students. Parents who are pursuing additional education to increase their earnings potential so they can better provide for their families should not be excluded from the Child Tax Credit.

Several other improvements to the Romney Child Tax Credit design are also worth making. First, policymakers should target the proposed increase in the credit. The Romney proposal would extend the full increase to married couples making $400,000 and single parents making $200,000. Any increase in the credit should instead begin phasing out at lower income levels. The Rescue Plan expansion, for example, began to phase down at incomes of $150,000 and $112,500 for married couples and heads of households.

In addition, one key way to improve the Romney plan’s earnings requirement would be to add a “lookback” feature that covers multiple years. If families need earnings to qualify for the Child Tax Credit, many will lose part or all of their credit if their work hours are cut or they become unemployed due to a recession. Moreover, even in good economic times, people can be out of work in a year for a number of reasons. That’s especially true in the low-wage job market, where workers have far less job security (simply getting sick can cost a worker their job, for example), little or no access to paid time off (let alone paid family and medical leave), and little or no market power compared to higher-paid workers. To account for such circumstances, any earnings requirement for the Child Tax Credit should allow parents to choose among the most recent two or three years of their earnings, not just the most recent year as under the Romney proposal.

Policymakers should reject the Romney proposal’s new requirement that caregivers not only live with the child but also have legal custody. This requirement, stricter than current law, could disqualify many grandparents and other relatives who care for children from claiming the credit.

Finally, a Child Tax Credit expansion ideally should allow children with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) rather than SSNs to receive the credit, as they could prior to the 2017 tax law and as they will again after 2025 under current law, in recognition of the importance of providing all children with the credit regardless of their immigration status. There is no reason to deny the Child Tax Credit to U.S. citizen children if their parents don’t have an SSN, as Romney proposes. The Romney proposal, even harsher than what Republicans enacted as part of the 2017 law, is directly at odds with the goal of expanding the Child Tax Credit and should be rejected.