States Have Flexibility to Move TANF Work Programs in an Antiracist Direction

End Notes

[1] For more on TANF’s racist history, see Ife Floyd et al., “TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance: Reimagined Program Should Center Black Mothers,” CBPP, August 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance.

[2] Ali Safawi and LaDonna Pavetti, “Most Parents Leaving TANF Work, But in Low-Paying, Unstable Jobs, Recent Studies Find,” CBPP, November 19, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/most-parents-leaving-tanf-work-but-in-low-paying-unstable-jobs.

[3] Ibid; Nina Banks, “Black women’s labor market history reveals deep-seated race and gender discrimination,” February 19, 2019, Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/blog/black-womens-labor-market-history-reveals-deep-seated-race-and-gender-discrimination/.

[4] Table 4B in Office of Family Assistance (OFA), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Department of Health & Human Services (HHS), “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Separate State Programs — Maintenance of Effort (SSP-MOE): Work Participation Rates and Engagement in Work Activities,” 2020, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ofa/wpr2020table04b.pdf.

[5] Laura Meyer, Ife Floyd, and LaDonna Pavetti, “Ending Behavioral Requirements and Reproductive Control Measures Would Move TANF in an Antiracist Direction,” CBPP, February 23, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/ending-behavioral-requirements-and-reproductive-control-measures.

[6] LaDonna Pavetti, “TANF Studies Show Work Requirement Proposals for Other Programs Would Harm Millions, Do Little to Increase Work,” November 13, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-studies-show-work-requirement-proposals-for-other-programs.

[7] American Public Human Services Association, “Core Principles for TANF Modernization,” April 2021, https://files.constantcontact.com/391325ca001/4251ff7a-5206-4cc3-8e3c-c360b320f9a6.pdf.

[8] Congressional Research Service (CRS), “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF): Welfare Waivers,” June 4, 2013, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42627/16.

[9] Liz Schott and LaDonna Pavetti, “Changes in TANF Work Requirements Could Make Them More Effective in Promoting Employment,” CBPP, February 26, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/changes-in-tanf-work-requirements-could-make-them-more-effective-in.

[10] Floyd et al., op. cit.

[11] Kendra Bozarth, Grace Western, and Janelle Jones, “Black Women Best: The Framework We Need for An Equitable Economy,” Roosevelt Institute and Groundwork Collaborative, September 2020, https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/RI_Black-Women-Best_IssueBrief-202009.pdf.

[12] American Public Human Services Association, “Core Principles for TANF Modernization: A Legislative Framework for TANF Reform,” March 2022, https://files.constantcontact.com/391325ca001/905334d8-53b0-4cae-89a3-7892d31c11b4.pdf.

[13] Floyd et al., op. cit.; Elisa Minoff, “The Racist Roots of Work Requirements,” Center for the Study of Social Policy, February 2020, https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Racist-Roots-of-Work-Requirements-CSSP-1.pdf.

[14] Ellen Mutari, Marilyn Power, and Deborah M. Figart, “Neither Mothers Nor Breadwinners: African-American Women’s Exclusion From US Minimum Wage Policies, 1912-1938,” Feminist Economics, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2002, p. 39, https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700210160988; Jill Quadagno, The Color of Welfare: How Racism Undermined the War on Poverty, Oxford University Press, 1994, pp. 17-32.

[15] Winifred Bell, Aid to Dependent Children, Columbia University Press, 1965, p. 34.

[16] Bell, op. cit., p. 46; Minoff, op. cit.

[17] Bell, op. cit., pp. 81-83.

[18] Susan W. Blank and Barbara B. Blum, “A Brief History of Work Expectations for Welfare Mothers,” The Future of Children, Vol. 7, No. 1, Spring 1997, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1602575.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Gene Falk, “The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: A Legislative History,” CRS, updated July 21, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44668.pdf.

[21] President Kennedy made two attempts at compromise: 1) creating the AFDC-Unemployed Parent (AFDC-UP) program, which allowed married couples with unemployed fathers to qualify for aid so long as the father entered work training; and 2) expanding psychosocial counseling and social services aimed at rehabilitating mothers. Neither initiative persuaded Southern Democrats that stricter work requirements weren’t needed, in part because they failed to lower the caseload. States had the option to implement these new polices, but no Southern states did so by the end of the decade. Years later, the federal government mandated that states create AFDC-UP programs. Eva Bertram, “Democratic Divisions in the 1960s and the Road to Welfare Reform,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 126, No. 4, Winter 2011-12.

[22] Premilla Nadasen, Jennifer Mittelstadt, and Marisa Chappell, Welfare in the United States: A History with Documents, 1935-1996, Routledge, 2009, pp. 46-47.

[23] Gene Falk, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF): Welfare-to-Work Revisited,” CRS, October 2, 2012, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42767/8.

[24] Minoff, op. cit.

[25] Minoff, op. cit.; Office for Human Services Policy, Office of Assistance Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), “A Brief History of the AFDC Program,” https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/167036/1history.pdf

[26] Bertram, op. cit.; “Herman Talmadge (1913-2002),” New Georgia Encyclopedia, August 14, 2020, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/herman-talmadge-1913-2002.

[27] Minoff, op. cit.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Leonard Goodwin, “What Has Been Learned from the Work Incentive Program and Related Experiences: A Review on Research with Policy Implications. Final Report,” National Technical Information Service, 1977, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED136011.pdf.

[30] “‘Welfare Queen’ Becomes Issue in Reagan Campaign,” New York Times, Reprinted from Washington Star, February 14, 1976, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1976/02/15/113445299.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[31] General Accounting Office, “Work and Welfare: Current AFDC Work Programs and Implications for Federal Policy,” January 29, 1987.

[32] Falk, 2020, op. cit.

[33] Paul Gorski, “The Myth of the Culture of Poverty,” from On Poverty and Learning, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228620924; Nadasen et. al., pp. 70-71.

[34] Bradley L. Hardy, “Income Instability and the Response of the Safety Net,” Contemporary Economic Policy, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2017; David A. Jaeger and Ann Huff Stevens, “Is Job Stability in the United States Falling? Reconciling Trends in the Current Population Survey and Panel Study of Income Dynamics,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 6650, 1998, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w6650/w6650.pdf.

[35] Banks, op. cit.; Martina Hund-Mejean and Marcela Escobari, “Our employment system has failed low-wage workers. How can we rebuild?” Brookings, April 28, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/04/28/our-employment-system-is-failing-low-wage-workers-how-do-we-make-it-more-resilient/.

[36] Janelle Jones, “Black Women Best,” Data for Progress, July 15, 2020, https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2020/7/15/black-women-best.

[37] Michael Dotsey, Shigeru Fujita, and Leena Rudanko, “Where Is Everybody? The Shrinking Labor Force Participation Rate,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Research Department, 2017, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/frbp/assets/economy/articles/economic-insights/2017/q4/eiq4_where-is-everybody.pdf; Bruce Western and Becky Pettit, “Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility,” Pew Charitable Trusts, 2010, https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf.

[38] Falk, 2020, op. cit.

[39] ASPE, op. cit.

[40] Lucy A. Williams, “Race, Rat Bites, and Unfit Mothers: How Media Discourse Informs Welfare Legislation Debate,” Fordham Urban Law Journal, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2011, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1440&context=ulj.

[41] Falk, 2020, op. cit.

[42] Michael Wiseman, “Welfare reform in the states: The Bush legacy,” Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin, https://irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus/pdfs/foc151b.pdf.

[43] See 1992 campaign ad by then-candidate Bill Clinton on “The Clinton Plan: Welfare to Work,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/politics/bill-clinton-in-1992-ad-a-plan-to-end-welfare-as-we-know-it/2016/08/30/9e6350f8-6ee0-11e6-993f-73c693a89820_video.html.

[44] Carol Harvey, Michael J. Camasso, and Radha Jagannathan, “Evaluating Welfare Reform Waivers Under Section 1115,” Journal of Economic Perspectives¸Vol. 14, No. 4, Fall 2000, pp. 165-188, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.14.4.165.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Minoff, op. cit.; Edward J. Rymsza, “The Contract With America: The Crystallization of the GOP’s Racial Agenda,” New York City Law Review, Vol. 1, 1996, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=clr.

[47] Andrew Glass, “Clinton signs ‘Welfare to Work’ bill, Aug. 22, 1996,” Politico, August 22, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/08/22/clinton-signs-welfare-to-work-bill-aug-22-1996-790321.

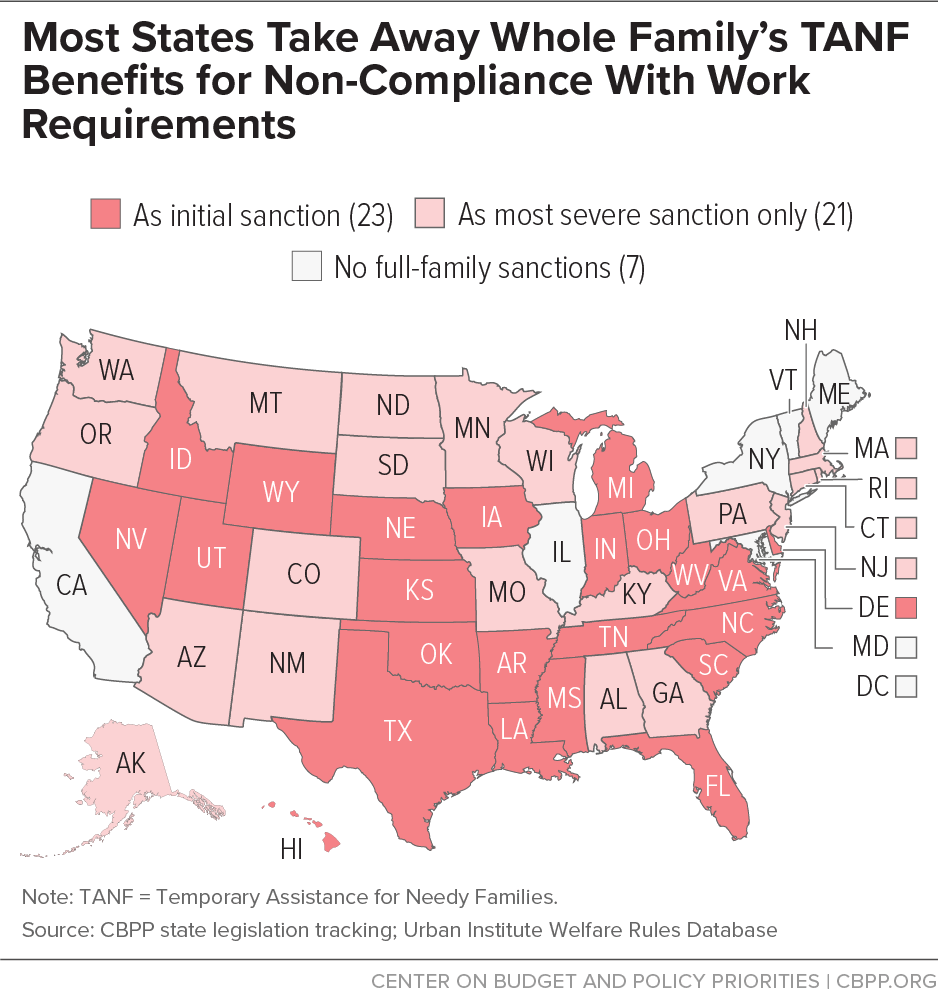

[48] Table III.B.2 in “Welfare Rules Databook: State TANF Policies as of July 2019,” Urban Institute, OPRE Report 2020-141, https://wrd.urban.org/wrd/Data/databooks/2019%20Welfare%20Rules%20Databook%20(final%2010%2019%202020).pdf.

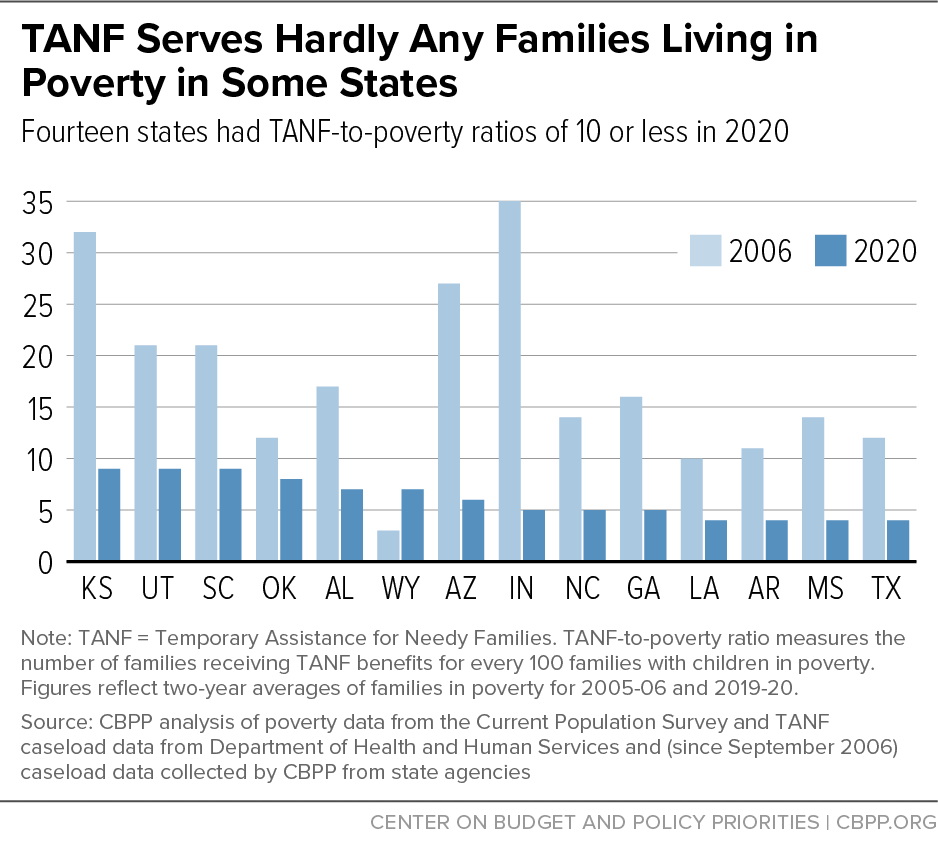

[49] Aditi Shrivastava and Gina Azito Thompson, “TANF Cash Assistance Should Reach Millions More Families to Lessen Hardship,” CBPP, updated February 18, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families-to-lessen.

[50] Blank and Blum, op. cit.

[51] Diana Azevedo-McCaffrey and Ali Safawi, “To Promote Equity, States Should Invest More TANF Dollars in Basic Assistance,” CBPP, updated January 12, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/to-promote-equity-states-should-invest-more-tanf-dollars-in-basic.

[52] Safawi and Pavetti, op. cit.

[53] Pavetti, op. cit.

[54] Floyd et al., op. cit.

[55] Banks, op. cit.

[56] Lincoln Quillian et al., “Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, October 10, 2017, Vol. 114, No. 41, https://www.pnas.org/content/114/41/10870/tab-article-info.

[57] Danyelle Solomon, Connor Maxwell, and Abril Castro, “Systematic Inequality and Economic Opportunity,” Center for American Progress, August 7, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2019/08/07/472910/systematic-inequality-economic-opportunity/.

[58] Marla McDaniel et al., “Identifying Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Human Services: A Conceptual Framework and Literature Review,” Urban Institute for Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, Department of Health and Human Services, November 2017, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/94986/identifying-racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-human-services_1.pdf.

[59] National Partnership for Women & Families, “Quantifying America’s Gender Wage Gap by Race/Ethnicity,” September 2020, https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/economic-justice/fair-pay/quantifying-americas-gender-wage-gap.pdf.

[60] Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “Fact sheet: Occupational segregation in the United States,” October 3, 2017, https://equitablegrowth.org/fact-sheet-occupational-segregation-in-the-united-states/; Will McGrew, “How workplace segregation fosters wage discrimination for African American women,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 28, 2018, https://equitablegrowth.org/how-workplace-segregation-fosters-wage-discrimination-for-african-american-women/; Kate Bahn and Will McGrew, “The intersectional wage gaps faced by Latina women in the United States,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, November 1, 2018, https://equitablegrowth.org/the-intersectional-wage-gaps-faced-by-latina-women-in-the-united-states/.

[61] Amanda Rossie, Jasmine Tucker, and Kayla Patrick, “Out of the Shadows: An Analysis of Sexual Harassment Charges Filed by Working Women,” National Women’s Law Center, August 2, 2018, https://nwlc.org/resources/out-of-the-shadows-an-analysis-of-sexual-harassment-charges-filed-by-working-women/; National Partnership for Women & Families, “By the Numbers: Women Continue to Face Pregnancy Discrimination in the Workplace: An Analysis of U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Charges (Fiscal Years 2011 – 2015),” October 2016, https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/economic-justice/pregnancy-discrimination/by-the-numbers-women-continue-to-face-pregnancy-discrimination-in-the-workplace.pdf.

[62] Jocelyn Frye, “On the Frontlines at Work and at Home: The Disproportionate Economic Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Women of Color,” Center for American Progress, (CAP) April 23, 2020, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/04/23/483846/frontlines-work-home/.

[63] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Women’s Health Insurance Coverage,” January 12, 2021, https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage/; Pronita Gupta et al., “Paid Family and Medical Leave is Critical for Low-wage Workers and Their Families,” Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), December 19, 2018, https://www.clasp.org/publications/fact-sheet/paid-family-and-medical-leave-critical-low-wage-workers-and-their-families.

[64] Banks, op. cit.

[65] Ava Kofman and Hannah Fresgues, “Black Workers Are More Likely to Be Unemployed but Less Likely to Get Unemployment Benefits,” Pro Publica, August 24, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/black-workers-are-more-likely-to-be-unemployed-but-less-likely-to-get-unemployment-benefits.

[66] Danilo Trisi and Matt Saenz, “Deep Poverty Among Children Rose in TANF’s First Decade, Then Fell as Other Programs Strengthened,” CBPP, February 27, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/deep-poverty-among-children-rose-in-tanfs-first-decade-then-fell-as.

[67] Safawi and Pavetti, op. cit.

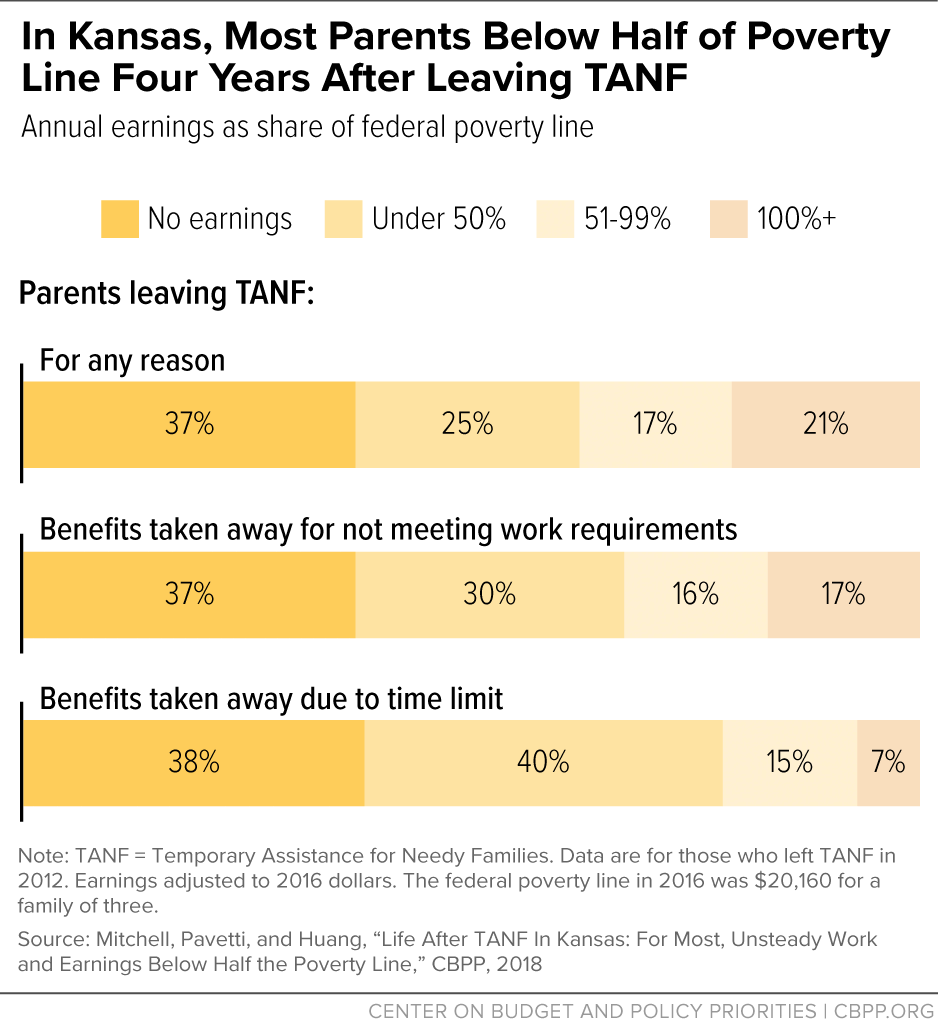

[68] See e.g. Rebecca McColl and Letita Logan Passarella, “Life After Welfare: 2019 Annual Update,” Ruth H. Young Center for Families and Children, University of Maryland School of Social Work, 2019, https://www.ssw.umaryland.edu/media/ssw/fwrtg/welfare-research/life-after-welfare/life2019.pdf.

[69] Tazra Mitchell, LaDonna Pavetti, and Yixuan Huang, “Life After TANF in Kansas: For Most, Unsteady Work and Earnings Below Half the Poverty Line,” CBPP, updated February 20, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/life-after-tanf-in-kansas-for-most-unsteady-work-and-earnings-below.

[70] Rework America Alliance, “Unlocking experience-based job progressions for millions of workers,” June 2021, https://www.markle.org/sites/default/files/Unlocking-Job-Progressions-Full-Report.pdf.

[71] Dan Bloom, Pamela J. Loprest, and Sheila R. Zedlewski, “TANF Recipients with Barriers to Employment,” Urban Institute, August 2011, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/25396/412567-TANF-Recipients-with-Barriers-to-Employment.PDF.

[72] Marla McDaniel et al., op. cit.; LaDonna Pavetti, Michelle K. Derr, and Heather Hesketh, “Review of Sanction Policies and Research Studies,” Mathematica Policy Research, March 10, 2003, https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-findings/publications/review-of-sanction-policies-and-research-studies-final-literature-review.

[73] Marla McDaniel et al., op. cit.; Lynda McDonnell, “Seven Years of Welfare Reform — Weighing the Results: A Summary of Research Findings on the Minnesota Family Investment Program,” Center for Urban and Regional Affairs and the Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare, University of Minnesota, December 2004, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED485767.pdf.

[74] Sanford F. Schram et al., “Deciding to Discipline: Race, Choice, and Punishment on the Frontlines of Welfare Reform,” American Sociological Review, January 2009, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27736070.

[75] Joe Soss et al., “Setting the Terms of Relief: Explaining State Policy Choices in the Devolution Revolution,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 45, No. 2, Apr. 2001, http://urban.hunter.cuny.edu/~schram/ssvosettingthetermsofrelief.pdf; Heather Hahn et al., “Why Does Cash Welfare Depend on Where You Live? How and Why State TANF Programs Vary,” Urban Institute, June 5, 2017, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/why-does-cash-welfare-depend-where-you-live.

[76] Valerie Wilson, “Black women face a persistent pay gap, including in essential occupations during the pandemic,” Economic Policy Institute, August 2, 2021, https://www.epi.org/blog/black-women-face-a-persistent-pay-gap-including-in-essential-occupations-during-the-pandemic/; authors’ analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Household Data Tables A2 and A3.

[77] Rework America Alliance, op. cit.

[78] U.S. departments of Labor, Commerce, Education, and Health and Human Services, “What Works in Job Training: A Synthesis of the Evidence,” July 22, 2014, https://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/jdt/jdt.pdf.

[79] Marla McDaniel et al., op. cit.

[80] Jennifer Stuber and Mark Schlesinger, “Sources of stigma for means-tested government programs,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 63, No. 4, August 2006, pp. 933-945, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.012.

[81] Schott and Pavetti, op. cit.

[82] 45 Code of Federal Regulations, §261.10 (a) (1).

[83] 45 Code of Federal Regulations, §261.10 (a) (2).

[84] State of Texas, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Work Verification Plan,” revised January 30, 2020, https://www.twc.texas.gov/files/partners/temporary-assistance-needy-families-work-verification-plan-twc.pdf#:~:text=On%20January%2031%2C%202012%2C%20TWC%E2%80%99s%20three-member%20Commission%20%28Commission%29,or%20received%20a%20high%20school%20equivalency%20%28HSE%29%20credential.

[85] Table 4B in OFA, op. cit.