BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The 2016 Labor-HHS-Education bill that the House Appropriations Committee is considering today would continue to force the Social Security Administration (SSA) — whose work touches nearly every American’s life — to do more with less.

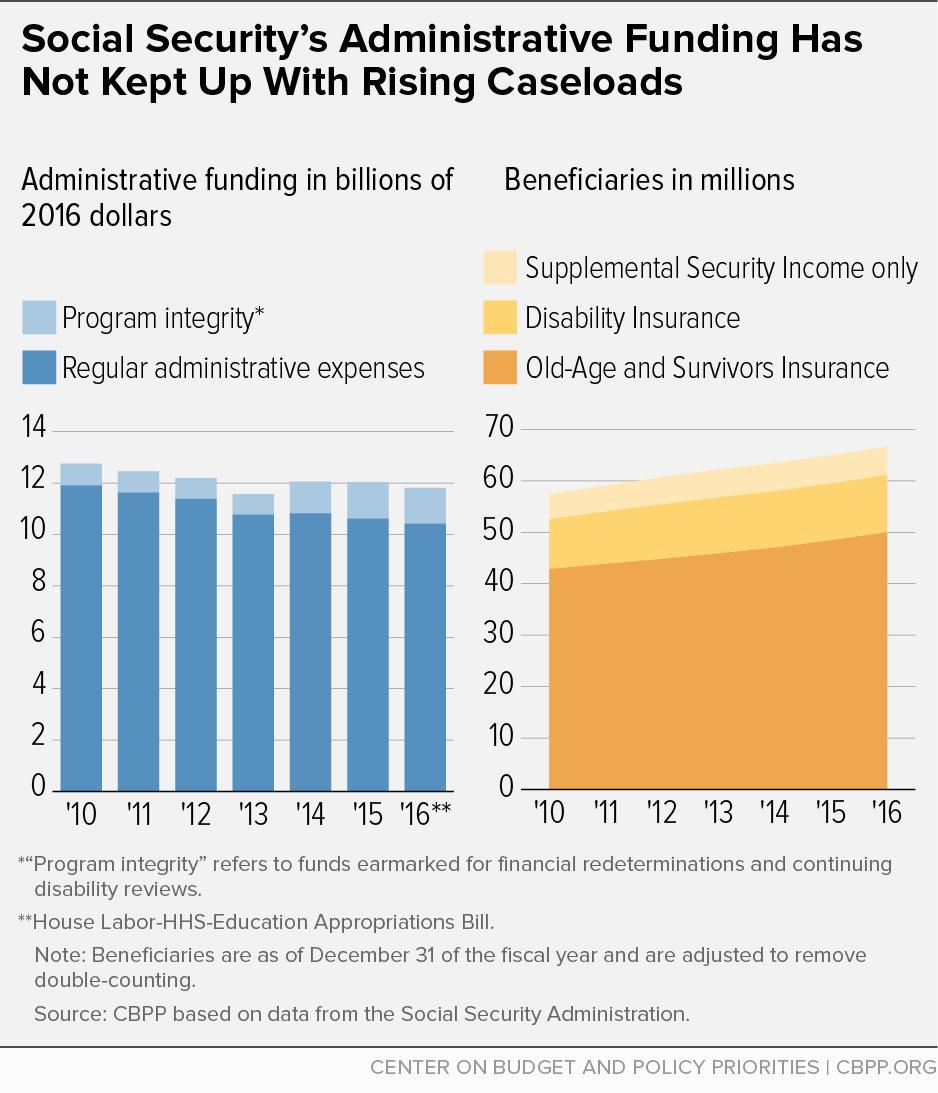

The 2011 Budget Control Act’s (BCA) tight funding caps, further reduced by sequestration, are squeezing Social Security. SSA’s “core,” or regular, administrative funding has fallen by over 10 percent since 2010 after adjusting for inflation, despite rising workloads as baby boomers retire. (See graph.) The 2016 House bill freezes funding at this year’s levels, failing to account for either inflation or rising workloads. (Along with core funding, appropriation bills can provide extra funds exclusively for program integrity work, a special adjustment that lies outside the BCA caps, but the bill doesn’t take full advantage of this option, providing only some of what’s allowable.)

SSA is widely viewed as well managed. It provides benefits to nearly 60 million retirees, disabled workers, dependents, and survivors, and a smaller number of Supplemental Security Income beneficiaries, and it responds to millions of inquiries from beneficiaries, workers, and employers. The demands on SSA have risen, particularly as baby boomers have aged into their peak years for disability and retirement; between 2010 and 2015, the number of beneficiaries rose by about 13 percent. Yet Congress keeps asking SSA to do more with less, in terms of both funding and staff. Since 2010, SSA has lost over 6,000 employees, nearly 10 percent of its staff. As a result, SSA’s service is suffering:

- Reduced field office hours. Starting in 2011, SSA cut the hours people can visit field offices. Field offices now close at noon on Wednesdays, and at 4 p.m. on other weekdays. Staff use the rest of the day to do behind-the-scenes work, like clearing backlogs.

- Increased wait times for appointments. SSA must handle the same number of appointments in less time, which has driven up wait times. Field office appointment calendars are often fully booked 60 days ahead. Wait times for walk-ins have more than doubled since before the reduction in hours began.

- Longer hold times. Wait times for Social Security’s 800 number have spiked to over 22 minutes — up from only 3 minutes in 2010. And that’s for people lucky enough to get through. The busy rate is over 13 percent. The situation is even worse for people who call local field offices.

- Cutbacks in Social Security Statements. In response to funding cuts, SSA stopped mailing annual Social Security Statements summarizing earnings and projected benefits to workers in 2011. After Congress restored some of SSA’s funding in 2014, SSA started sending statements every five years to workers who have not signed up to see their statements online.

- Backlogged Disability Insurance claims. The average processing time for an initial disability claim has held fairly steady at three to four months. However, denied applicants who appeal typically wait well over a year for a decision. Budget constraints contribute to the backlog.

- Delays in processing earnings reports. Some beneficiaries must report their earnings or other changes in circumstances to SSA, but SSA cannot keep up with these self-reports. When this happens, even people who honestly report their earnings to SSA may be overpaid and have their subsequent benefits withheld.

In sharp contrast to the House bill, the President proposes to increase the SSA budget by over $600 million, a 6 percent increase — enough to cover inflation and restore some of the ground lost since 2010. To make room for the funding increase, the President’s budget provides sequestration relief, offset with alternative savings. Congress should agree to provide sequestration relief, which would allow additional funding for essential services such as those the SSA provides.