BEYOND THE NUMBERS

States Should Strengthen Unemployment Insurance Systems to Weather Possible Downturn Ahead

A recession may or may not be around the corner, but the chances are significant enough that states should be prudent and take steps to bolster their unemployment insurance (UI) systems and, in some cases, to reverse recent years’ policies that have weakened them. Investments in state UI programs should be prioritized over calls for wasteful tax cuts that will leave states underprepared for economic downturn.

States with too few maximum weeks of benefits should increase those maximums, and all states should raise their maximum benefit amounts. All states should also fix their outdated eligibility requirements, which leave out too many unemployed workers, particularly women, people of color, and people who are immigrants.

UI serves a vital role for workers and state economies by providing cash benefits to eligible workers who have been laid off from their jobs. The program becomes especially crucial during economic downturns, when more people lose their jobs and when declining household spending can deepen and lengthen the downturn. Following massive and rapid job losses at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, an expansive set of new UI benefits provided on an emergency basis by the federal government helped saved millions of people from severe hardship.

When workers are laid off, having some level of income through the UI system can help them avoid immediate financial distress and outcomes like eviction, food insecurity, and even homelessness. And UI benefits enable jobless workers to continue purchasing goods and services, helping to keep businesses afloat, to prevent additional layoffs, and to keep the recession from becoming worse.

While the federal government provides some minimal program requirements, states have significant flexibility over nearly every facet of basic UI policies. That includes benefit levels and duration, eligibility criteria, adjustment of employer tax rates, and the extent and duration of prior employment required to qualify for benefits. This broad flexibility has resulted in a patchwork of state UI systems with varied abilities to support workers when they lose their jobs, including during recessions. Policies some states have enacted over the past few years, such as cutting back on the duration of benefits, have significantly weakened their unemployment systems.

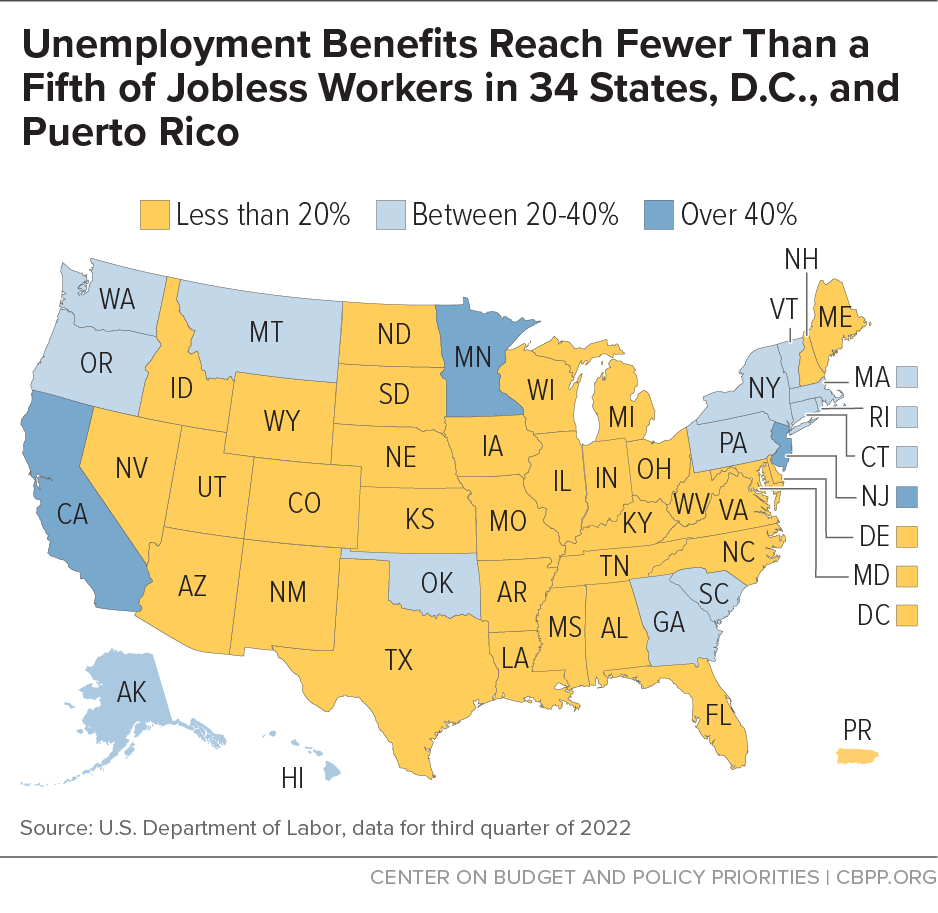

The result of these varied and often harmful policy approaches is that UI benefits currently reach fewer than 20 percent of jobless workers in 34 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. (See map.) In three states — Alabama, North Carolina, and South Dakota — less than 1 in 10 unemployed workers receive benefits. Conversely, California, Minnesota, and New Jersey are the only states in which more than 40 percent of eligible workers receive UI payments. Despite increased recipiency during recessions, no year since 1975 has seen national UI recipiency come close to reaching 50 percent until Pandemic Unemployment Assistance was temporarily established in 2020 to expand UI coverage to workers usually excluded from the program.

In the face of continued economic uncertainty, and with a possible downturn looming, states should bolster their UI systems this legislative session in the following ways:

- States with too few weeks of maximum benefits should increase those maximums. From the 1960s until recent years, every state provided a maximum of 26 weeks or more of benefits for eligible jobless workers. Since the Great Recession, many states have cut the maximum weeks allowed, regardless of economic conditions. In 2022 alone, four state legislatures enacted laws to reduce the number of weeks of unemployment benefits. Even in the pandemic, nearly half of states chose to stop providing federally funded emergency UI benefits before their scheduled end in September 2021, leaving millions of people without income for months and forfeiting an estimated $2 billion in consumer spending. Today, 12 states allow fewer than 26 weeks of UI benefits and two states — North Carolina and Florida — allow no more than 12 weeks, even in the worst recession. Short benefit duration can mean that a worker who is laid off from their job may lose UI benefits before they’re able to find a new role, or face pressure to take a job that’s a poor match for their skills and unlikely to keep them employed.

- All states should make UI eligibility more equitable. Most state UI systems also have outdated eligibility requirements that leave out many unemployed workers, particularly women, people of color, and immigrants. Few states offer UI benefits to people who need to leave their jobs for reasons such as to care for a sick family member. Many states require workers laid off from part-time jobs — including parents caring for young children — to seek full-time employment to qualify for UI. Because people of color are more likely to hold jobs that pay low wages, provide unstable hours, or fail to provide paid sick or family leave, these rules exacerbate racial inequity, especially for Black, Latina, and Native American women, who hold intersecting identities and face both racial and gender discrimination. Women in general are much likelier than men to work in part-time jobs and to leave work for caregiving responsibilities. In addition, Black workers are more likely than workers of other races to live in the South, where states have adopted some of the most restrictive UI eligibility rules in the country. Immigrants without documented status, meanwhile, are locked out of receiving UI benefits altogether. Several states made a commendable effort in the pandemic to offer them direct cash support, and Colorado has established a new program to do so permanently — more states should join it as they address the many inequities in UI eligibility.

- All states should raise benefit amounts. UI benefits that are too low to adequately replace workers’ lost wages make it harder for families to stave off hardship and for the broader economy to rebound from recession. States vary widely in the value of the average weekly UI benefit they provide: in 12 states and the District of Columbia, it’s only a quarter or less of the state’s average weekly wage, compared to it being nearly half the average weekly wage in Hawai’i, Iowa, Montana, and North Dakota. All states should raise benefits to more effectively support workers, and should make concerted efforts to address the potential effect of biases within the broader labor market on their UI systems. For example, Black workers at every education level are paid less than similar white workers, and lower-paid workers are less likely to meet monetary eligibility requirements for UI in many states. States could account for that bias and make their UI systems more equitable with some sensible reforms designed to lower or remove barriers to receiving benefits, as states like Massachusetts and Washington have done.

Improving UI systems by increasing benefits, lengthening their duration, and broadening eligibility to workers previously left out can strengthen the protective effects of UI for both workers and state economies. Common-sense reforms adopted today would help states face whatever lies ahead, whenever the next downturn might come.