BEYOND THE NUMBERS

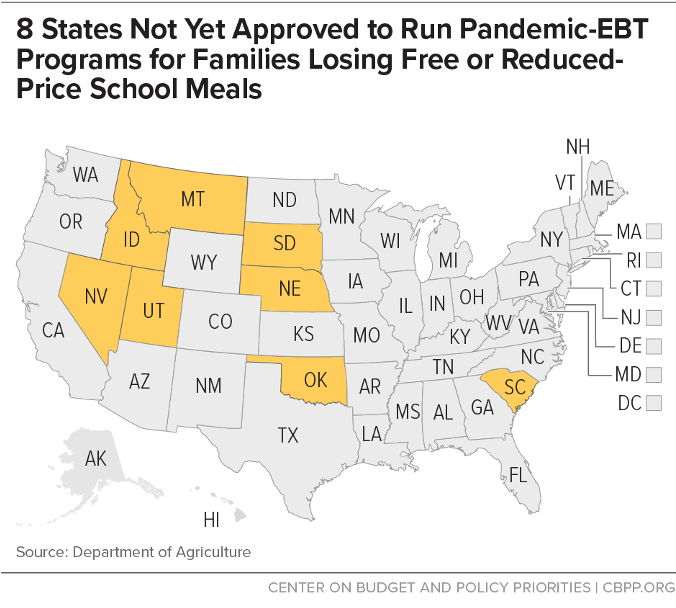

A staggering 1 in 3 families with children say they don’t have enough food, and that’s in part because schools where lots of children normally eat free or reduced-price meals are closed. A new federal program (Pandemic-EBT, or P-EBT) is beginning to compensate families for the added expense of feeding these children, but eight states — Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Utah — have yet to fully participate.

The other 42 states and the District of Columbia, with nearly 28 million (or 93 percent) of the nearly 30 million children approved for free or reduced-price school meals, have received federal approval to offer P-EBT. Benefits are now flowing in many of these states. For each day that schools are closed, families receive the $5.70 per child that otherwise would have gone to the school district to help cover the meals. For children who were previously approved for free or reduced-price meals, benefits are retroactive to the date that schools closed.

Providing additional food assistance to families with children through P-EBT and other programs is critical to mitigating the deepening racial and ethnic disparities resulting from COVID-19. Like many of the pandemic’s other devastating consequences, food insecurity isn’t affecting all groups equally. Food insecurity during the crisis is far more common among black (29 percent) and Hispanic (34 percent) families than white families (18 percent).

P-EBT is especially important for the 1.9 million families with school-age children who haven’t received a SNAP benefit increase during the pandemic because they were already poor enough to receive the maximum SNAP benefit. Without P-EBT benefits to compensate for missed school meals, many of the poorest families with children — a group that consists disproportionately of families of color, due to the impact of historical racism and ongoing discrimination — are receiving less food assistance during the pandemic than they did before.

For all these reasons, the 2.2 million children in the remaining eight states must receive P-EBT benefits. Some of these states have submitted plans to operate programs and others are working on applications, but it’s not clear whether every state intends to apply. If these states don’t ultimately provide P-EBT benefits, the families in question will lose out on about $114 per child for each month that a school is closed.

Launching a P-EBT program can prove challenging. States must compare databases across multiple programs and school districts to identify eligible children, obtain accurate addresses, load cards, and mail them. All that takes time, which is why states moved slowly in getting these programs going. But states can surmount these challenges, and all states must adopt this option to get additional food assistance to eligible children. Food insecurity among children is no small matter — it demands our leaders’ action.

Moreover, now that most states have launched P-EBT, federal policymakers should extend this highly efficient method of delivering food assistance to younger children, into the summer, and then into the next school year if necessary because of continued school and child care disruptions.