BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Early data on rising food insecurity during the pandemic and deep economic crisis reveal how widespread the hardship is becoming, underscoring the need for a robust policy response — including raising maximum SNAP (food stamp) benefits and fixing SNAP limitations in the relief measures enacted thus far.

Nearly a third of non-elderly adults reported that their families spent less on food in the last month, according to a nationally representative Urban Institute survey with responses from late March and early April. That number rises to 46.5 percent among adults in families that experienced job or income loss. And it’s making it harder for families to get enough to eat: food insecurity is spiking, particularly among families with children.

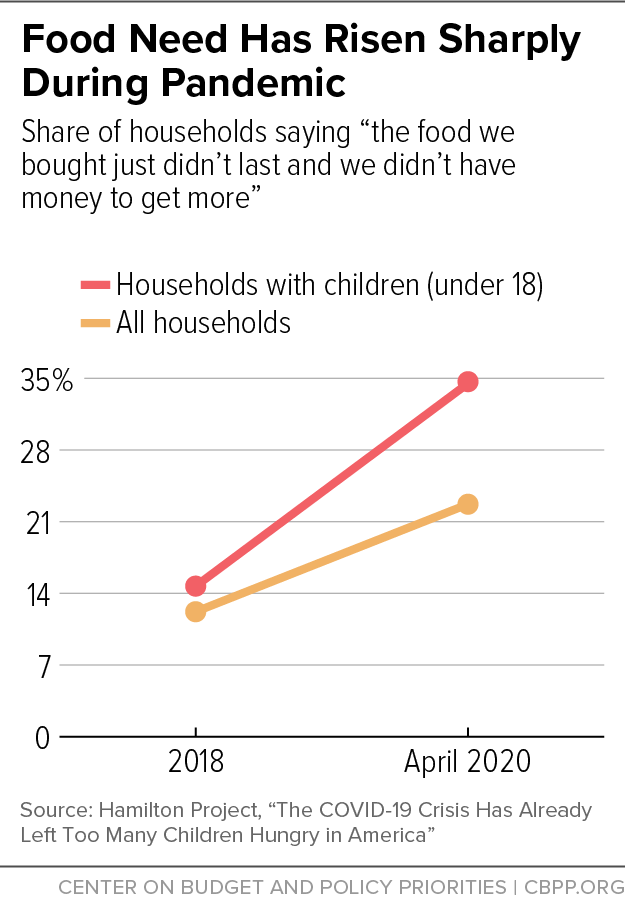

- Nearly 23 percent of households said the food they bought “just didn’t last” and they didn’t have the money to buy more, according to a national survey from late April. That compares to about 12 percent of households in 2018 and 16 percent during the worst point of the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009.

- Food needs have more than doubled from 2018 levels among households with children, with nearly 35 percent reporting that the food they bought didn’t last and they didn’t have the money to buy more, compared to 15 percent in 2018. (See chart.)

- Nearly 1 in 5 mothers of young children (12 and under) reported that their children weren’t eating enough — a level five times higher than in 2018 — because they couldn’t afford enough food, according to a nationally representative survey from late April. Because parents often skip meals or eat less themselves so their children have enough to eat, the share of children who don’t get enough to eat is usually far smaller than the share of households.

Hardship isn’t limited to food insecurity, the data show. Over two-thirds of adults in families with income at or below the poverty level reported experiencing one or more hardships, such as being unable to pay rent or a mortgage or skipping medical care due to cost. Low-income families, families with children, and communities of color are among the hardest hit. Many were already struggling to pay their rent and put food on the table, and they may have significant trouble weathering the crisis on their own.

We called raising SNAP benefits now a “no-brainer” because doing so during the Great Recession boosted income and reduced hardship while generating economic stimulus to help convert the recession into an economic recovery. The 2009 Recovery Act’s SNAP benefit increase reduced very low food security (when at least one household member has to skip meals or otherwise eat less) among SNAP recipients at a time when it was expected to rise due to income and job losses.

The new survey findings are troubling and, even though they may not yet reflect the receipt of recently enacted relief benefits, we know that a more robust policy response is needed. The measures enacted to date that were meant to help families and individuals during the pandemic don’t provide enough for those at the highest risk of health and hardship. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, for example, lets states raise households’ SNAP benefits to the current maximum amount, but that doesn’t help families already getting the maximum. About 40 percent of SNAP households with the lowest incomes won’t benefit.

An elevated need for food assistance and economic relief will persist far longer than the official health emergency, and many of the provisions enacted to date to help families and individuals during the pandemic will likely end before the economy recovers. If policymakers don’t take the necessary steps, the rise in hardship and food need among families will likely become only clearer as more data become available.