BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The federal government has been operating under stopgap funding measures (continuing resolutions or CRs) since fiscal year 2022 began on October 1, and Republicans’ failure thus far to join negotiations over 2022 appropriations bills raises the prospect that a CR largely freezing program funding at last year’s levels could remain in place for the rest of this fiscal year. That would reverse the progress over the past few years in alleviating the squeeze on non-defense appropriations resulting from the deep cuts required by the 2011 Budget Control Act. In fact, such a full-year CR would leave non-defense appropriations outside veterans’ medical care about 12 percent below their 2010 level, after adjusting for inflation and population growth. It would also block needed increases for a wide range of priorities.

The House Appropriations Committee has approved all 12 regular appropriations bills for 2022 and the full House has passed nine of them. The Senate Appropriations Committee has approved three 2022 appropriations bills and Committee Chair Patrick Leahy has released proposed texts of the remaining nine. However, appropriations bills will need 60 votes in the Senate to avoid a filibuster, so Senate passage will require some bipartisan cooperation.

The Democratic chairs of the House and Senate Appropriations committees have called for bipartisan negotiations and are urging the Republican side to put forward specific proposals of their own as a basis for discussion. But the Republican leaders of the two committees haven’t yet agreed to enter negotiations. Rather, Republicans reportedly are demanding that Democrats first agree to extensive changes in their spending bills, including much less funding for non-defense priorities, more funding for defense, and major changes to legislative provisions.

If the process remains stalled, 2022 appropriations could end up governed by a full-year CR, with funding for most programs frozen at 2021 levels. Normally, CRs are temporary measures, adopted at the start of a fiscal year to continue funding at the prior year’s level until Congress enacts the regular appropriations bills. An initial CR was in effect until December 3, and last week Congress extended that CR through February 18 to allow further time for negotiations. But once that time runs out, if congressional negotiators can’t draft appropriations bills that can pass the Senate as well as the House, the most likely result is a CR lasting through the fiscal year.

While a full-year CR would have funding adjustments in some program areas, funding for most areas would likely be frozen at prior-year levels. Some congressional Republicans have suggested this would be an acceptable outcome. That raises the concern that Republicans might agree to only extremely limited funding adjustments within a full-year CR.

A full-year-freeze CR could create all sorts of problems. A freeze is effectively a cut, as rising costs mean fewer services can be provided with the same amount of money. Further, a freeze would lock in last year’s funding priorities and ignore this year’s new needs. It would also fail to provide for the many important investments in the President’s 2022 budget and the committee-approved House and Senate appropriations bills, including in public health, education, services for veterans, environmental protection, scientific research, and resources for agencies like the Social Security Administration to properly serve the public. The chairs of the House and Senate Appropriations committees and the Office of Management and Budget have detailed many of these consequences.

A full-year-freeze CR would be especially harmful given the considerable austerity in non-defense appropriations caused by the Budget Control Act, which set caps on overall defense and non-defense appropriations for each year from 2012 through 2021. Beginning in 2013, those caps were further reduced by a “sequestration” process triggered when Congress failed to agree on other deficit-reduction measures; the caps were then gradually raised as both parties recognized they were too tight to meet national needs.

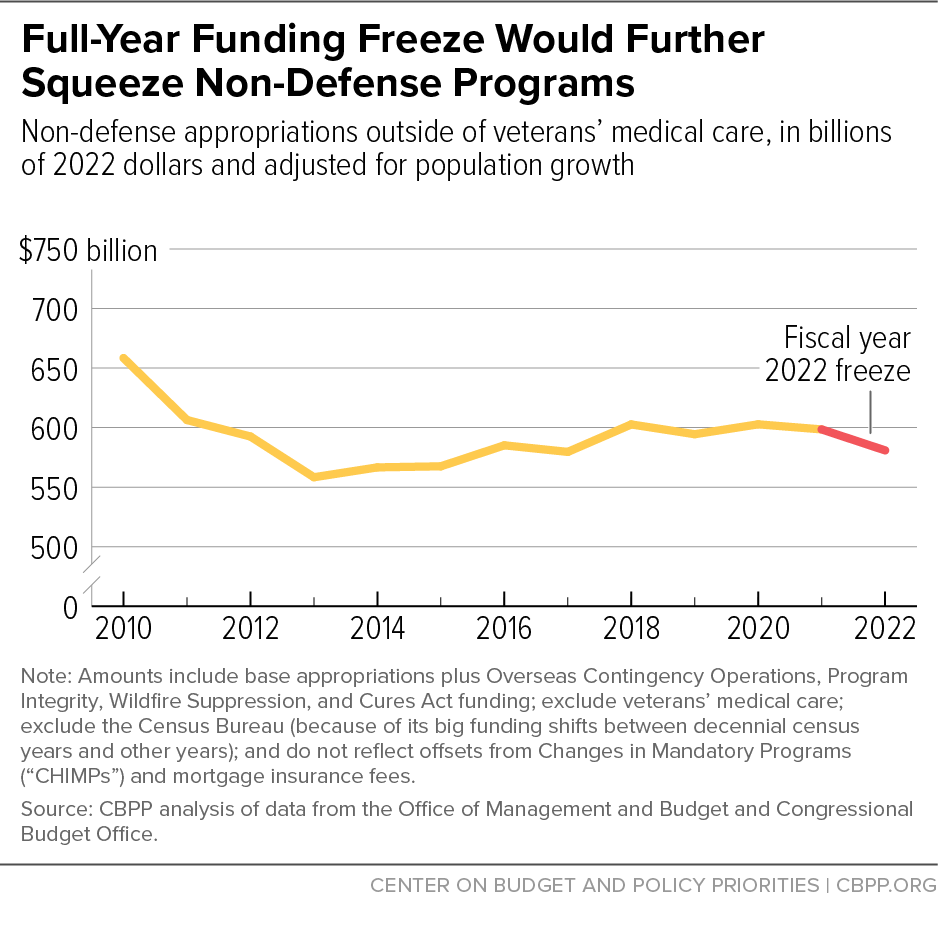

After adjustment for both inflation (which increases program operating costs) and population growth (which increases the number of people the federal government serves), overall non-defense funding fell by about 3 percent between 2010 — the year before the cuts began — and 2021. And for most non-defense programs the constraints were significantly tighter due to the large funding increases needed to maintain and improve medical care for veterans — a very high priority for Congress. Veterans’ medical care is the largest non-defense appropriated program, accounting for roughly one-seventh of all regular funding in 2021, and its funding grew substantially between 2010 and 2021. As a result, funding for non-defense programs other than veterans’ medical care fell by 9 percent between 2010 and 2021, after adjustment for inflation and population growth.

For these non-defense programs outside of veterans’ medical care, a full-year CR freezing funding at 2021 levels would leave 2022 appropriations even further below the 2010 level — about 12 percent below 2010, after adjusting for inflation and population. (See graphic.) It would set funding below the 2018 level after both adjustments, rolling back the cap increases enacted for the past four years.

Further, if the CR is extended through the end of the current fiscal year, it’s likely to be extended into the next fiscal year, pending the outcome of the midterm elections. And if differences still aren’t resolved, it could be extended for all of 2023, increasing shortfalls and locking in place old priorities.

Congress should enact appropriations for 2022 adequate to address the nation’s needs, rather than punt by imposing a full-year freeze.