- Home

- Federal Budget

- Boosts In Non-Defense Appropriations Nee...

Boosts in Non-Defense Appropriations Needed Due to Decade of Cuts, Unmet Needs

Congress and the President, no longer bound by multi-year caps on discretionary funding, have the opportunity this year to reset non-defense discretionary funding levels to remedy existing shortfalls; improve services to people; and make investments that will help redress inequalities, strengthen education and science, protect the environment, and build a stronger and more equitable economy.

Non-defense appropriations — often referred to as “non-defense discretionary” (NDD) funding — support a wide range of important services. They fund aid to education, medical care for veterans, scientific and medical research, housing and other assistance for families in need, public health measures, treatment for substance use disorders, national parks and forests, weather forecasting, the Coast Guard, international assistance, air traffic control, rural development programs, upgrades to wastewater and drinking water treatment, job training, and many other things.

Some of these activities have received substantial additional funding over the past year in response to urgent needs arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting recession. This paper, however, focuses on regular annual NDD funding to address the wide range of ongoing priorities just described, and on the decisions about future NDD funding that Congress and the President will be making in the coming months.

For the past decade, appropriations have been limited by statutory caps on defense and non-defense appropriations that were set by the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and expire at the end of the current fiscal year. The caps were established in advance for a ten-year period and subsequently reduced by a process called sequestration, which was triggered by policymakers’ failure to agree on additional deficit reduction measures.

Within a few years, Congress recognized that the caps were too tight and began amending the BCA to raise them somewhat. Nevertheless, significant austerity in most appropriated programs resulted. For NDD programs other than veterans’ medical care — the largest single NDD program — inflation-adjusted regular funding in 2021 is 3 percent lower than it was 11 years ago. If also adjusted for population growth, the decrease is 10 percent. Moreover, the reductions were larger in the earlier years under the BCA before being gradually reversed, producing a loss of services and investments that has yet to be recovered. By contrast, funding for veterans’ medical care rose by 67 percent on an inflation-adjusted basis between 2010 and 2021, reflecting congressional determination to fix serious problems in the system, keep up with rising medical care costs, and improve care for veterans.

These topline numbers translated into cuts and shortfalls in a wide range of NDD-funded programs. To give just three examples, regular appropriations for federal aid to K-12 education — which is largely targeted to increasing opportunity and promoting success for disadvantaged students and students with disabilities — has decreased by 11 percent since 2010. (All percent changes in this paragraph are on an inflation-adjusted basis.) Appropriations for operating the Social Security Administration have fallen by 13 percent over this period, while the number of beneficiaries has risen by 21 percent. And appropriations for loan funds that help communities replace aging or inadequate drinking water systems have fallen by 33 percent since 2010.

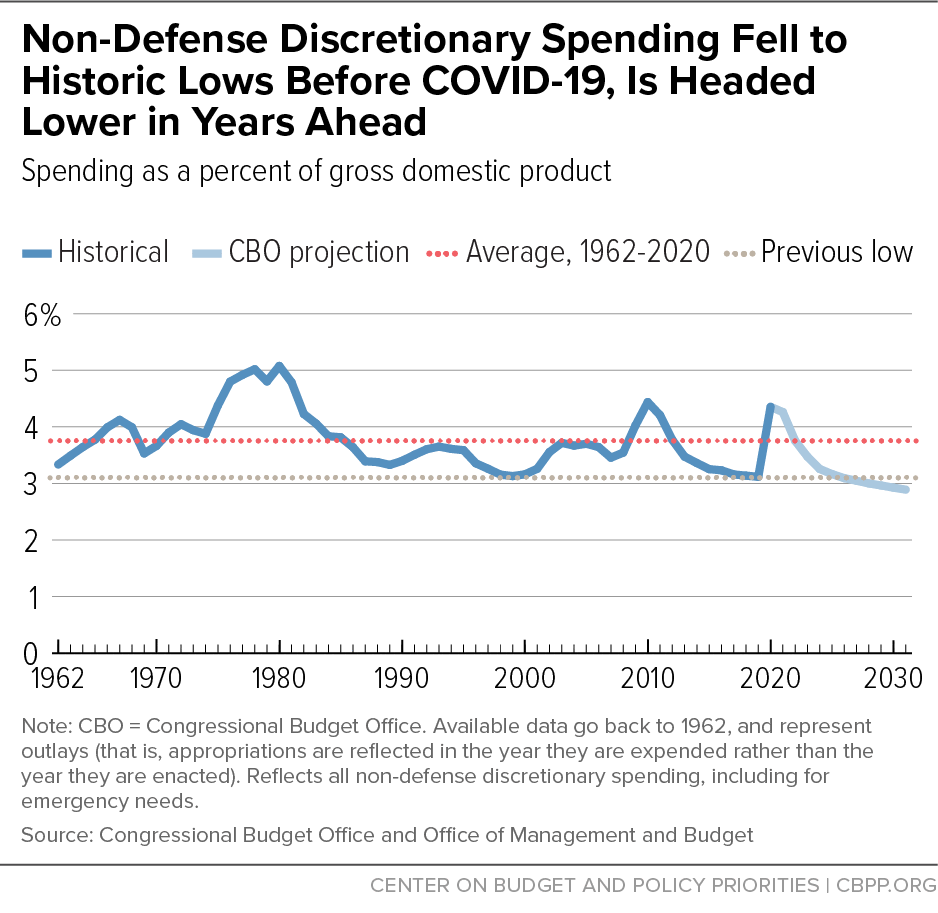

When we measure spending relative to the size of the economy — that is, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), a standard way of looking at longer-term budget trends — we see that the percentage rises during recessions, as recession relief spending increases while GDP falls. That trend has occurred during the current recession and public health emergency. But recession-induced NDD spending is temporary, and so fades as the economy recovers. The longer-term trend shows that spending on these programs has declined as a percentage of the economy for the last several decades.

The NDD portion of the federal budget entered the COVID-19 emergency from a historic low point, with NDD spending as a percentage of GDP in 2019 in a tie for the lowest on record since the data series began in 1962.Indeed, the NDD portion of the federal budget entered the COVID-19 emergency from a historic low point, with NDD spending as a percentage of GDP in 2019 in a tie for the lowest on record since the data series began in 1962. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections show the percentage gradually falling back to pre-recession levels as the economy recovers, absent increases that do more than just offset the effects of inflation.

Policymakers should use the expiration of the Budget Control Act’s arbitrary spending caps at the end of the current fiscal year as an opportunity to reconsider the needs that NDD appropriations serve and the funding levels required to meet those needs. Going forward, Congress should set appropriations toplines sufficient to address shortfalls, make necessary investments, and more fully assist those in need.

What’s Funded by Non-Defense Appropriations?

Non-defense appropriations — also known as non-defense discretionary funding — support a wide range of federal activities, investments, and assistance. The category is called “discretionary” because Congress has the discretion to set funding levels through the annual appropriations process, as distinct from entitlements and other “mandatory” programs where funding is determined by the underlying law governing the program. The analysis in this paper does not reflect any of the emergency appropriations for COVID-19 relief.[1] Rather, it focuses on regular appropriations for ongoing programs and services — as Congress will soon be considering for fiscal year 2022.

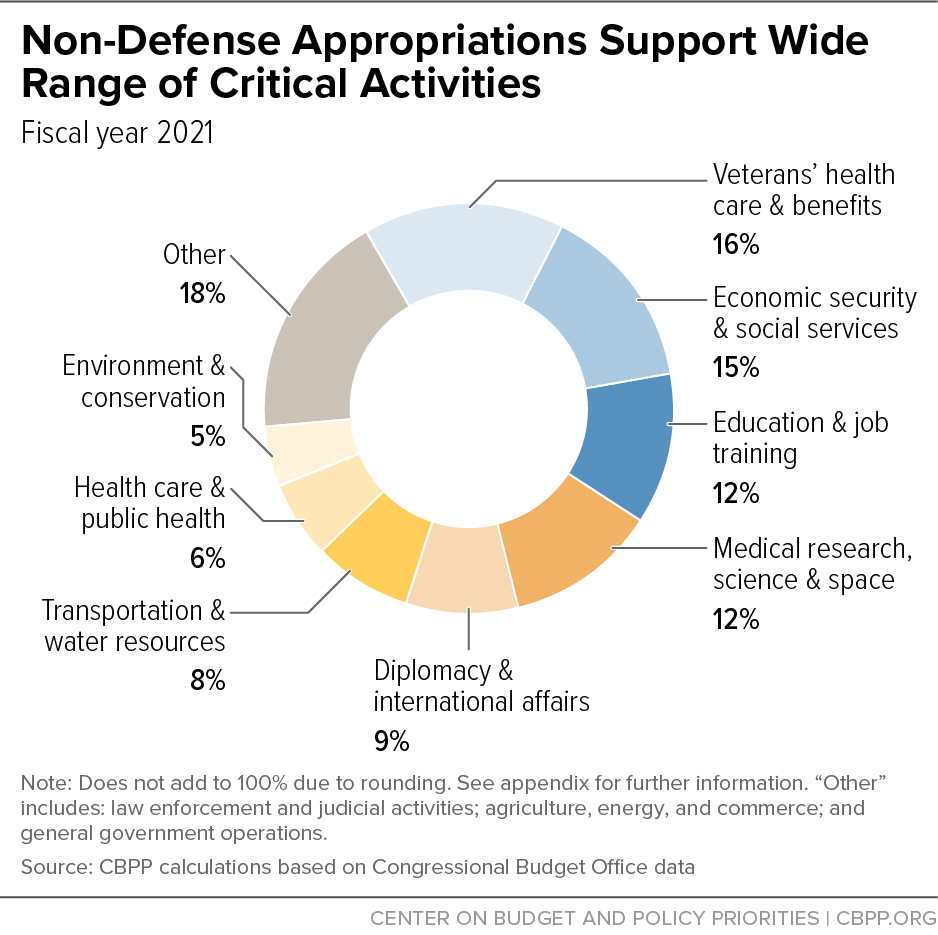

The following are some of the diverse and important program areas funded by NDD appropriations (see Figure 1 and Appendix Table 2):

- Health care and other services for veterans. This is now the largest category within non-defense appropriations, making up roughly one-seventh of the 2021 total. About 90 percent is for veterans’ medical care, which is currently funded entirely on the discretionary side of the budget. The remaining amounts are mostly for the operating expenses of the Department of Veterans Affairs, including administrative costs for benefits supported with mandatory funding.

- Education and job training. NDD appropriations provide almost all federal support for elementary, secondary, and vocational education and for job training, as well as about three-quarters of federal support for higher education (including Pell Grants and other student financial aid). About half of this year’s total is for K-12 education.[2]

- Economic security and social services. NDD appropriations also fund important low-income assistance and social services programs. Examples include housing assistance, Head Start, Low-Income Home Energy Assistance (LIHEAP), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Older Americans Act programs, along with part of child care assistance. This category also covers the administrative expenses of Social Security, other retirement programs, and Unemployment Insurance.

- Medical and scientific research and space exploration. This is another area where almost all federal funding comes through NDD appropriations. Of the total appropriated in 2021, more than half is for research and training at the National Institutes of Health and other health agencies. The rest is for NASA, the National Science Foundation, and Department of Energy labs.

- Public health and health services. NDD appropriations are also the main source of federal funding for public health programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other Department of Health and Human Services agencies. They also support grants for treatment of opioid addiction and other substance use disorders and for mental health services, as well as the Indian Health Service and various other health care programs.

- Transportation and water resources. NDD appropriations play an important role in infrastructure investments, including by funding the navigation, flood control, and other civil works projects of the Army Corps of Engineers and various programs at the Department of Transportation (such as air traffic facilities and equipment, mass transit capital funding, and railroad programs).[3] This category also includes operating expenses of those agencies.

- Environment, national parks, and conservation. About four-fifths of funding in this category comes through NDD appropriations. This funding goes to the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Park Service, the Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and several other conservation and land management agencies, as well as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In addition to the areas mentioned above, NDD appropriations support a wide variety of other important functions and services, such as law enforcement and federal courts; the State Department and international assistance programs; the Internal Revenue Service; agricultural research and services; the Census Bureau and other statistical agencies; and economic and community development programs.

The Budget Control Act’s Legacy: Austerity, Unmet Needs

For the past ten years, appropriations totals have been governed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 and a series of amendments to that law.

The BCA was a key element in resolving a standoff over the debt limit between the Obama Administration and congressional Republicans. Among other things, it established legally binding caps on appropriations for 2012 and each of the following nine years, to be enforced by automatic across-the-board cuts if breached. These caps superseded the usual process established by the Congressional Budget Act, which provides for setting discretionary appropriations totals year by year in congressional budget resolutions.

The basic BCA appropriations caps were set to hold funding below the levels needed to simply keep up with inflation. Their starting point was the enacted 2011 level, which already reflected substantial cuts that had been made after party control shifted in the House in January 2011. Thus, in effect the BCA began by locking in the cuts enacted in 2011.

A second element of the BCA added a further round of cuts, in an unsuccessful effort to create an incentive for Congress to enact revenue increases and cuts to mandatory programs. The BCA set up a bipartisan Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to recommend such measures, and provided that unless the Joint Select Committee made recommendations sufficient to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion over ten years and those recommendations were enacted into law by January 15, 2012, additional automatic cuts would take effect. Those would be imposed though a process termed “sequestration,” largely operating once again on discretionary appropriations, which would be divided into defense and non-defense categories for that purpose. The specified cuts were to be made across the board to programs in each of those two categories in 2013, and thereafter by reducing the caps that would otherwise apply for each of 2014 through 2021. Despite the threat of these further automatic cuts, the Joint Select Committee did not agree on deficit reduction legislation, putting the sequestration process into effect.

In short, the BCA created a series of tight caps on appropriations extending ten years into the future, which were further reduced by the additional cuts triggered by the failure of the Joint Select Committee. There was no particular policy or economic rationale for these cuts. Moreover, the sequestration cuts were intended to be so unacceptable as to produce a broader budget agreement. That strategy failed, leaving in place a series of appropriations limits that had been designed to be unacceptable.

Over the following decade, Congress gradually reduced the BCA cuts, mostly through a series of amendments covering two years at a time, but the BCA nevertheless produced substantial austerity in NDD appropriations over the period as a whole.

Prolonged Austerity in Appropriated Funding

The BCA caps and sequestration cuts produced a tight squeeze on programs and services that are supported through appropriations. The low point was in 2013, as the sequestration process triggered by failure of the Joint Select Committee began, leaving overall inflation-adjusted NDD funding 12 percent below its 2010 level.[4] (This paper compares BCA funding levels to those in 2010 because Congress began cutting NDD programs in 2011, and that initial round of cuts was the base for the BCA caps.)

NDD funding gradually increased in the years after 2013, reflecting the series of agreements that amended the BCA two years at a time. These amendments scaled back — but did not eliminate — the sequestration cuts for 2014 through 2017. Beginning in 2018 the amendments eliminated sequestration and also provided increases above the pre-sequestration caps. By 2021, inflation-adjusted NDD funding was 3 percent above its 2010 level. (See Appendix Table 1.)

Over that long a period, it is also useful to add an adjustment for population growth, to take note of the increasing number of people the federal government serves and as a general reflection of the nation’s growth. When adjusted for both inflation and the 7.5 percent growth in the U.S. population, NDD funding in 2021 is 4 percent below 2010.

For most of the programs within the NDD category, the constraints were somewhat tighter than the overall numbers suggest, because of substantial funding increases needed to maintain and improve veterans’ medical care. Appropriations for that purpose rose 67 percent between 2010 and 2021 on an inflation-adjusted basis. That increase was largely concentrated in the latter part of the period, with the annual inflation-adjusted growth reaching 12 percent in 2021 alone. These rising costs have a substantial effect on NDD as a whole because veterans’ medical care now accounts for about one-seventh of all NDD funding.

The growth in veterans’ medical funding reflects the high priority that Congress places on meeting veterans’ needs. Contributing factors include rising health care costs in general, demographic factors, and resources needed to fix serious problems in the system such as long waiting times for care. In addition, during the past decade Congress enacted legislation (the MISSION Act of 2018) expanding veterans’ access to health care from non-federal providers and adding additional services. These developments — largely unforeseen when the Budget Control Act was enacted 2011 — are a good illustration of the drawbacks to setting arbitrary targets for appropriations years into the future.

For all NDD programs other than veterans’ medical care, inflation-adjusted funding in 2021 was 3 percent below its level 11 years earlier. (See Figure 2 and Appendix Table 1.) After adjusting for population growth, which is important to take into account when looking over extended periods given the increasing needs of a growing population, the decrease from 2010 to 2021 was 10 percent.

Further, looking only at the net change between those two years doesn’t capture the much larger decreases that occurred in the early and middle parts of the decade before being partially reversed. For all years 2010-2021 taken together, NDD funding excluding veterans’ medical care was $496 billion below levels needed to keep up with inflation since 2010 and $757 billion below levels needed to keep up with inflation and population growth.

That gap translates into less investment in maintaining and upgrading technology and facilities, less progress in addressing inequalities in education or housing, less support for infrastructure investments, less scientific research, and poorer service to the public by government agencies, among other consequences. Some of that simply represents lost opportunities to assist and serve, but in many cases maintenance not done and investments in technology and infrastructure not made will also lead to higher costs in the future.

Reductions between 2010 and 2021 were spread broadly throughout the NDD budget. That can be seen in Figure 3, which shows funding changes over that period for broad groupings of federal programs, after adjustment for inflation and population growth. Apart from veterans’ programs, net funding fell for each of these categories between 2010 and 2021.

Many Shortfalls and Unmet Needs Exist

These high-level trends translate into numerous areas where significant cuts have occurred or serious unmet needs exist. Some of these cuts affect the ability of agencies like the Social Security Administration or the Internal Revenue Service to serve the public. Funding constraints also limit efforts to foster equity and improve opportunity for people of color in areas like education, or to assist low-income families with child care or housing. Still others affect public health or infrastructure investments. Consider the following examples, which reflect the wide range of programs funded through NDD appropriations, and the harm the BCA’s austerity has caused since 2010:

- Social Security Administration. Inflation-adjusted funding for the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) operating expenses fell by 13 percent between 2010 and 2021, while the number of beneficiaries grew by 21 percent. These cuts have hampered the agency’s ability to perform its essential services, such as timely determinations of eligibility for benefits, responding to questions from the public, and updating benefits promptly when circumstances change. Since 2010, the number of staff handling SSA’s national 800 number has fallen by 12 percent even as call volume has grown by 6 percent, resulting in more busy signals, more hang-ups, longer waits, and fewer calls answered. Fundamentally, cuts to the Social Security Administration’s budget mean reduced service to the public.

- IRS. The IRS budget, in particular its enforcement function, remains severely depleted following nearly a decade of funding cuts starting in 2011. In real terms, IRS funding has been cut by 19 percent since 2010. Over that same period, the IRS lost nearly a third of its enforcement staff. These cuts have caused the overall audit rate to drop by more than half. In particular, audits of high-income tax filers have plummeted, contributing to a projected tax gap of about $7.5 trillion over the next decade. At the same time, the IRS answers fewer than a quarter of calls from people seeking help with their taxes.[5]

-

Aid to elementary and secondary education. Appropriations for the federal government’s modest but important contribution to K-12 education fell by 11 percent between 2010 and 2021, adjusted for inflation. Most of this federal aid is for programs that promote equity and educational opportunity for disadvantaged students and students with disabilities.

Within the total, funding for “Title I” Aid to Disadvantaged Students fell 6 percent between 2010 and 2021, adjusted for inflation. This program provides grants to local school districts via the states to fund additional services and supports to help students from low-income families succeed. It assists roughly 25 million students in more than half of the nation’s schools. Federal aid also funds grants under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which help school districts cover the cost of special education services for more than 7 million children with disabilities. IDEA funding has fallen by 8 percent since 2010, adjusted for inflation. While the American Rescue Plan did invest resources to address challenges specific to COVID-19, these funds were not designed to address the equity and opportunity issues that should be addressed through regular discretionary funds — leaving these critical accounts underfunded compared to 2010 levels.

- Financial aid for college students. Pell Grants, which provide financial assistance to undergraduate students from low- and middle-income families, are funded primarily through NDD appropriations. About one-third of all undergraduate students receive Pell Grants, which vary in amount according to income and need and are designed to help ensure equal access to postsecondary education for all. The inflation-adjusted value of the maximum Pell Grant has fallen by 4 percent since academic year 2010-2011, while tuition and room and board costs have continued to rise, according to analysis by the College Board. In 2010-2011 the maximum grant covered 34 percent of average tuition and room and board costs at four-year public colleges. By 2020-2021 it covered just 29 percent.[6]

- Housing assistance. Federally supported rental assistance helps 10 million seniors, children, and others in 5 million households keep a roof over their heads, often by helping them afford rental housing they find in the private market. But many more struggle to pay rent without the help of federal aid. As of 2018, 11 million households paid more than half their income for rental costs, a severe financial burden that exacerbates families’ poverty and hardship and increases their risk of eviction and homeless — 47 percent more than in 2001.[7] Nearly 9 in 10 of these households had annual incomes of less than $30,000, and more than half had incomes of less than $15,000. Close to half of the households struggling to pay rent are Black or Latinx, a disproportionately high share. Because of inadequate funding, however, only 1 in 4 eligible households in need of assistance receives it, a lower share than in 2001. Renters’ struggles have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, and while federal aid has helped address some of this increased need, the large majority of eligible households still do not receive housing assistance.

- Child care. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States was facing a child care crisis, especially for young children. Child care is often prohibitively expensive, with one study finding that center-based child care would cost the median low-income family 28 percent of their income. Black and Latinx families are most likely to experience unaffordable child care.[8] These barriers have very real effects for both families and our society, forcing many mothers to leave the workforce. Though annual appropriations for Head Start and the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) have risen in recent years, significantly more funding is needed to match the scale of child care needs. In 2016, the last year with available data, just 12 percent of eligible children received subsidies through the CCDBG. Asian, Latinx, and American Indian and Alaska Native communities were particularly underserved, with only 5 percent, 8 percent, and 9 percent of eligible children receiving subsidies, respectively.[9]

-

Infrastructure for drinking water and wastewater treatment. The nation needs to invest in drinking water and wastewater treatment facilities to ensure access to safe drinking water and to reduce water pollution. The American Society of Civil Engineers’ latest Infrastructure Report Card gave the nation’s drinking water systems a grade of C- and wastewater systems a D+, noting among other things that major components of many systems are nearing the end of their useful life and are in need of repair or replacement.[10] The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has estimated that capital investment totaling $744 billion is needed over a 20-year period simply to meet health and environmental standards.[11]

To help meet the needs of communities that would otherwise have difficulty financing necessary investments, the EPA operates Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds. Appropriations provide capital for these funds, which states use to make low-interest loans to public wastewater and drinking water systems for constructing and upgrading facilities, with larger subsidies and partial loan forgiveness available in situations of particular need. Appropriations for the revolving loan funds have been cut substantially since 2010, however, with inflation-adjusted funding down by 36 percent for the clean water fund and 33 percent for the drinking water fund.

-

Disease control and public health. The COVID-19 pandemic has vividly illustrated the need for an effective public health system with strong capabilities in epidemiology, laboratory testing, contact tracing and other epidemic control measures, distribution and administration of vaccines, and public education, as well as in other public health functions such as addressing environmental health problems and promoting good health practices.

Nevertheless, appropriations for the primary national public health agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), fell by 7 percent between 2010 and 2021, after adjustment for inflation. The CDC is also an important source of funding for state and local health departments and other partners. One of its many ongoing grant programs is for state and local public health preparedness, designed to improve readiness to meet public health emergencies like the current one. Funding for those grants fell 20 percent from 2010 to 2021 on an inflation-adjusted basis.[12]

- Behavioral health services. Though funding for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has increased over the last decade, significant unmet needs remain. Nearly 1 in 5 U.S. adults live with some form of mental illness, and only half of them receive treatment, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.[13] Fewer than 13 percent of the 21 million-plus people who need substance use services get any.[14] Many factors contribute to this gap, including stigma, limited access to affordable mental health services, and a shortage of psychiatrists. The ripple effects of inaccessible behavioral health care contribute to job loss, homelessness, incarceration, and premature death. While Medicaid should be the foundation of behavioral health funding for people with low incomes, NDD grants through SAMHSA play an essential role in filling funding gaps.[15] Additional behavioral health grants are needed to serve people who are under- or uninsured, test new and emerging treatments, and fund training and other efforts to strengthen provider capacity. Grants are also needed to promote more equitable access to care, such as responding to trends in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids (such as fentanyl) that are a major driver in the recent uptick in opioid overdose deaths for Black and Latinx people.[16] To meet these needs, Congress should continue to strengthen SAMHSA’s funding.

NDD Spending Reached a Historic Low as a Share of the Nation’s Resources Under the BCA

A standard way of looking at budget trends over long periods of time is by measuring spending relative to the size of the economy — that is, as a percentage of GDP. These long-term data are based on expenditures (“outlays”) which often lag behind appropriations (or “budget authority,” the data used elsewhere in this paper). They include all NDD spending, including for emergencies, while the data used in elsewhere in this paper exclude emergency funding.[17]

Looking at spending relative to GDP is another way of taking into account the nation’s overall growth, as well as the growth in the nation’s economic resources.

Figure 4 shows NDD outlays as a percentage of GDP back to 1962. It also includes CBO projections for future years. Those projections assume that most NDD appropriations will increase from the 2021 level at a rate sufficient to keep pace with inflation. They do not, however, assume that emergency COVID-19-relief NDD appropriations enacted in 2021 will be repeated in future years.[18]

Three points emerge from these data and projections:

- Not surprisingly, NDD outlays as a percentage of GDP tend to rise during recessions, as recession-relief spending increases while GDP falls. The substantial increase in the ratio in 2020 and 2021 reflects that fact (including the substantial increase in spending to address the health emergency created by the pandemic). Similar trends can be seen in Figure 4 around the Great Recession of 2007-09.

- Outside of those periods, NDD spending relative to the size of the economy has been trending downward since the early 1980s. In the fiscal years immediately preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, 2018 and 2019, NDD spending was 3.1 percent of GDP, equal to the lowest level on record since the beginning of this data series in 1962.

- CBO’s projections show this percentage shrinking as the economy recovers, falling below the long-term historical average of 3.8 percent by 2023, returning to the historical low of 3.1 percent by 2026, and continuing to fall thereafter — even with NDD programs growing with inflation, as CBO projections assume.

In sum, the current levels of NDD spending relative to the economy are elevated, which is consistent with times of recession and emergency. But the NDD portion of the federal budget entered the COVID-19 emergency from a historically low point in that ratio. That suggests there will be room in coming years to strengthen support for some of the important services and investments funded through NDD appropriations.

The Need for Robust NDD Appropriations Going Forward

With the Budget Control Act and its caps expiring at the end of the current fiscal year, the rules for setting appropriations toplines will once again be those established by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. Those rules provide for Congress to set an appropriations total annually, through a congressional budget resolution.[19] In years when a budget resolution is not adopted, Congress has established a topline number through more informal processes.

Policymakers should use the occasion created by the BCA’s expiration to take a fresh look at appropriations and set totals that will be more adequate to meet national needs.

Given how central veterans’ medical care costs have become in the NDD total, the topline for the coming year should be set at a level sufficient to accommodate the increases necessary to continue fixing problems in the system and to provide high-quality care to all eligible veterans — and to do so without squeezing appropriations for other needs.

The topline should also be adequate to allow for the start of longer-term investments in strengthening and rebuilding various programs where funding has fallen short of what’s needed to provide adequate services, address inequalities, make necessary investments, and more fully assist those in need.

Appendix

Basis for Funding Data Used in This Paper

Except where the text indicates otherwise, numbers used in this paper for NDD appropriations represent funding subject to the caps set by the BCA, along with adjustments to better reflect actual programmatic funding. The adjustments are as follows:

- Two categories of offsets to appropriations are excluded from our figures. One is changes to mandatory programs made in appropriations bills (commonly known as “CHIMPs”), which provide savings to the discretionary appropriations measure that contains them and thereby allow higher program funding within the bill. The other is fee income derived from receipts from mortgage insurance at the Department of Housing and Urban Development (FHA/GNMA). Excluding these offsets (but not the funding they offset) better focuses the analysis on actual funding for appropriated programs.

-

Certain categories of funding not subject to the caps are included to provide a more complete picture of overall non-defense appropriations trends. These categories are overseas contingency operations (“OCO”) funding for certain war-related costs of the State Department and other international agencies (note that this reflects only the non-defense portion of OCO; the largest share of OCO flows to the Defense Department), program integrity funding intended to help identify and eliminate fraud and abuse in areas such as federal health care programs and disability benefits, and funding to support management and control of wildfires.

Two other categories of funding outside the caps — emergencies and disaster relief — are not included because their amounts fluctuate greatly from year to year, are unpredictable, and are not related to underlying NDD trends.

- Finally, the account that funds decennial censuses is also removed, to avoid distortions resulting from the fact that 2010 was a decennial census year while 2021 is not.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBPP Non-Defense Discretionary Funding Adjustment | ||||

| In billions of 2021 dollars |

Percent Change, 2010 - 2021 |

|||

| Non-Defense Discretionary Funding | 2010 | 2021 | Adjusted for Inflation | Adjusted for Inflation & Population |

| Budget Control Act cap (or 2010 comparable amount) | 644.5 | 626.5 | -2.8% | -9.5% |

| Remove major offsets: | ||||

| Changes in Mandatory Programs (CHIMPs) | 6.7 | 25.3 | ||

| FHA/GNMA fee income | 5.0 | 10.7 | ||

| Add funding not subject to the cap: | ||||

| Overseas contingency operations | 4.6 | 8.0 | ||

| Program integrity | 1.9 | |||

| Wildfire suppression | 2.4 | |||

| Remove account that funds decennial census | -8.3 | -0.8 | ||

| Programmatic Funding | 652.5 | 673.9 | 3.3% | -3.9% |

| Veterans' medical care | 56.9 | 95.2 | 67.1% | |

| Programmatic Funding, excluding Veterans’ Medical Care | 595.5 | 578.7 | -2.8% | -9.6% |

Source: CBPP analysis of data from the Office of Management and Budget and Congressional Budget Office.

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Further Detail on NDD Funding by Category | |||||

| Non-Defense Discretionary Funding, by Major Category | 2010 | 2021 | Adjusted for Inflation | Adjusted for Inflation & Population | 2021, Percent of Total NDD |

| Veterans’ Health Care & Benefits | 64.5 | 104.9 | 63% | 51% | 16% |

| Medical Research, Science, & Space | 74.9 | 78.5 | 5% | -2% | 12% |

| Law Enforcement & Judicial Activities | 64.1 | 67.0 | 5% | -3% | 10% |

| Health Care & Public Health | 39.5 | 40.9 | 4% | -4% | 6% |

| Economic Security & Social Services | 101.1 | 103.6 | 3% | -5% | 15% |

| Transportation & Water Resources | 51.5 | 50.6 | -2% | -9% | 8% |

| Education & Job Training | 91.1 | 83.8 | -8% | -14% | 12% |

| Environment, Parks & Conservation | 36.1 | 33.1 | -8% | -15% | 5% |

| Diplomacy & International Affairs | 65.9 | 57.5 | -13% | -19% | 9% |

| Agriculture, Energy, & Commerce | 38.7 | 31.3 | -19% | -25% | 5% |

| General Government Operations | 25.0 | 19.8 | -21% | -26% | 3% |

| Adjustment to reflect Congressional Budget Office (CBO) re-estimates* | 2.6 | ||||

| Total | 652.5 | 673.9 | 3.3% | -3.9% | 100% |

*These adjustments make the data used in this table (CBO baseline estimates released in February 2021) comparable to the estimates used in December 2020 in scoring the 2021 appropriations bills.

Note: The categories shown above are a simplified version of the standard functional classifications used in the federal budget.

Source: CBPP analysis of data from the Office of Management and Budget and Congressional Budget Office.

End Notes

[1] It excludes emergency appropriations provided in the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, Families First Coronavirus Response Act, CARES Act, and the December 2020 relief package. It also excludes COVID-19 relief funding provided in the American Rescue Plan Act for programs typically funded by appropriations.

[2] This analysis includes federal student loans. However, over time the loans that are made and the loan repayments plus interest that are repaid largely offset each other, and so have little effect on the total federal cost of higher education.

[3] This category does not include the highway and mass transit trust funds because that funding is considered mandatory.

[4] See the Appendix for an explanation of the numbers used for NDD funding in this paper. In general, they remove certain offsets and add certain ongoing funding outside the BCA caps, in order to focus on programmatic funding. These adjustments make the funding levels appear higher and the increase between 2010 and 2021 larger than it would be without them. The NDD levels used in this paper do not include funding outside the caps for disaster relief or to address other emergency needs, since that funding varies considerably from year to year in response to natural disasters and economic or health emergencies. In particular, they do not include any of the COVID-related emergency funding enacted during 2020 and 2021, as the focus of this paper is on funding for ongoing needs that will remain after the COVID-19 pandemic has receded.

[5] Chye-Ching Huang, “How Biden Funds His Next Bill: Shrink the $7.5 Trillion Tax Gap,” New York Times, March 10, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/10/opinion/deficits-taxes-biden-infrastructure.html.

[6] College Board, “Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2020,” October 2020, https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-college-pricing-student-aid-2020.pdf.

[7] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, “America’s Rental Housing 2020,” 2020, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2020.

[8] Maura Baldiga et al., “Child care is unaffordable for the majority of working parents, especially for low-income and black and Hispanic working parents,” Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy, Brandeis University, November 2018, https://www.diversitydatakids.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/child-care_update.pdf.

[9] Estimates refer to children eligible under each state’s eligibility limits. See Rebecca Ullrich, Stephanie Schmit, and Ruth Cosse, “Inequitable Access to Child Care Subsidies,” CLASP, April 2019, https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2019/04/2019_inequitableaccess.pdf.

[10] American Society of Civil Engineers, “2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure,” March 2021, https://infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/National_IRC_2021-report.pdf.

[11] The most recent reports are Environmental Protection Agency, “Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment,” March 2018, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2018-10/documents/corrected_sixth_drinking_water_infrastructure_needs_survey_and_assessment.pdf; and “Clean Watersheds Needs Survey 2012,” January 2016, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/cwns_2012_report_to_congress-508-opt.pdf.

[12] For a discussion of CDC budget trends and the effect on the national public health system, see Trust for America’s Health, “The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System,” April 2020, TFAH2020PublicHealthFunding.pdf.

[13] American Psychiatric Association, “Enhancing Public Health Investments Improve Access to Care,” March 9, 2019, https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/advocacy/federal-affairs/federal-funding; and National Institute of Mental Health, “Statistics,” https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/index.shtml.

[14] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” September 2020, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR1PDFW090120.pdf.

[15] Anna Bailey et al., “Medicaid Is Key to Building a System of Comprehensive Substance Use Care for Low-Income People,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 18, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-is-key-to-building-a-system-of-comprehensive-substance-use-care-for-low.

[16] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “The Opioid Crisis and the Hispanic/Latino Population: An Urgent Issue,” July 2020, https://store.samhsa.gov/product/The-Opioid-Crisis-and-the-Hispanic-Latino-Population-An-Urgent-Issue/PEP20-05-02-002; and “The Opioid Crisis and the Black/African American Population: An Urgent Issue,” April 2020, https://store.samhsa.gov/product/The-Opioid-Crisis-and-the-Black-African-American-Population-An-Urgent-Issue/PEP20-05-02-001.

[17] The outlay data include spending from the highway and mass transit trust funds because that spending is considered discretionary. In contrast, budget authority for these trust funds is considered mandatory, as mentioned in footnote 3, and so is not included in our analyses of NDD funding.

[18] These projections also do not include outlays for COVID-19 relief from the American Rescue Plan Act. All funds in that Act are classified as mandatory, not discretionary. They will raise spending overall, but on a temporary basis.

[19] The Congressional Budget Act calls for establishing a single topline total for discretionary appropriations (the “section 302(a)” allocation), encompassing both defense and non-defense programs. Since setting defense and non-defense totals separately has become customary under the BCA, it seems likely that budget resolutions will indicate the intended division of the total between the two parts, perhaps in the accompanying committee reports.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise