BEYOND THE NUMBERS

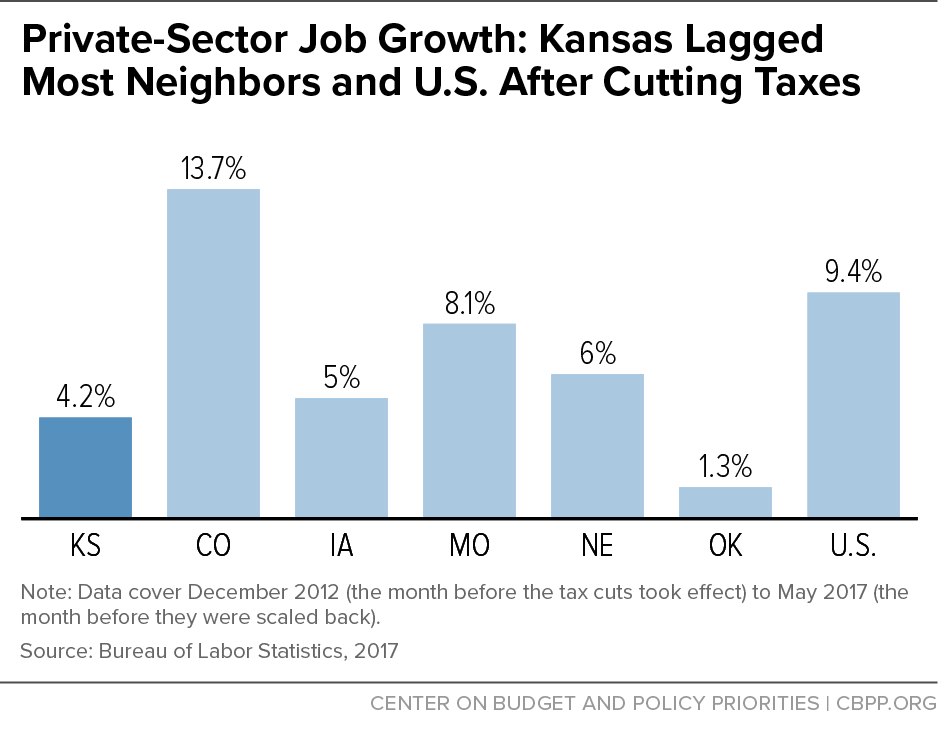

With Kansas Governor Sam Brownback’s confirmation this week as ambassador at large for international religious freedom, it’s an appropriate time to evaluate his legacy as governor — particularly his huge tax cuts enacted in 2012. At the time, he and other proponents helped sell the tax cuts with “supply-side” claims that cutting taxes on high-income people and businesses would spur exceptional growth by boosting job creation, work, and new business formation. It didn’t work. While the tax cuts were in effect, private-sector job growth was slower in Kansas than in the United States as a whole and in all but one of its neighboring states (see graph).

Now that the Republican-controlled state legislature has repealed (over Brownback’s veto) a large part of the tax cuts, which produced massive budget problems instead of faster growth, some of those former proponents now claim that the experiment was tainted and offers no lessons about state-level supply-side economics. But their three main arguments are unconvincing, as our major new report — which also reviews Kansas’ economic record under the tax cuts — explains:

- Kansas sharply constrained spending after enacting the tax cuts. Some conservatives argue that the tax cuts failed because lawmakers didn’t follow through with spending cuts. For example, American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) Vice President Jonathan Williams claimed: “Spending reductions necessary to implement the plan were eschewed in favor of other tax increases, making any honest judgement of the original plan’s success or failure impossible.” But state policymakers did, in fact, tightly constrain state spending following the tax cuts. Between fiscal years 2012 and 2016, General Fund spending rose only 0.3 percent without adjusting for inflation and fell 5.5 percent after adjusting for inflation and population growth.

If Kansas had cut spending more deeply, its economic performance would have been even worse. Fewer private-sector jobs would have been created, as teachers, nursing home aides paid with Medicaid funds, and road maintenance contractors would have had less money to spend in local stores. The state avoided deeper program cuts by draining its reserves (the General Fund balance fell from $709 million to an estimated $50 million between fiscal years 2013 and 2017).

- Downturns in agriculture, energy, and airplane manufacturing weren’t major factors. Heritage Foundation economist Stephen Moore, who helped design the tax cuts, wrote: “The state has underperformed on jobs and growth compared with the national average, but this is in part due to steep declines in the price of oil and gas (Kansas is an energy state) and the hit to farmers from historically low commodity prices.” Similarly, a 2017 ALEC report cited declines in Kansas’ energy and aviation sectors to help explain the state’s poor economic performance.

But the aircraft manufacturing and energy sectors are too small a part of the Kansas economy for their downturns to appreciably affect the state’s job creation record. The two sectors lost 2,500 and 3,100 jobs, respectively, between 2012 and mid-2017 — well under 1 percent of the state’s total employment.

And, while combined earnings of farm proprietors and employees fell by 9.6 percent in Kansas between 2012 and 2016, all of Kansas’ neighbors except Nebraska experienced even bigger declines, as did the United States overall. Yet Kansas’ job growth still lagged behind all but one of its neighbors.

- Kansas’ exemption of “pass-through” income from the income tax led to only modest tax avoidance. In 2017, the Cato Institute stated: “By completely eliminating the income tax on pass-through businesses, the Governor significantly increased opportunities for tax avoidance for individuals working in certain types of company. The take up of this provision was much, much higher than expected.”

The exemption for pass-through income — that is, income that the owners of businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships report on individual tax returns — did create an incentive for various kinds of tax avoidance strategies. As one example, employees could quit their jobs and go out on their own as self-employed (sole proprietor) contractors to their former employers, thereby exempting all their income from Kansas income tax. The currently available evidence suggests, however, that taxpayers adopted these sorts of strategies only to a modest extent. For example, a sophisticated statistical analysis found no evidence of artificial formation of S corporations or partnerships and only minor evidence of artificial formation of sole proprietorships.

Regardless of how much tax avoidance occurred, if supply-side theory were valid, the exemption should have prompted the formation of many new businesses. It didn’t.

In sum, contrary to supporters’ excuses for the tax cut failure, the Kansas experience adds to the already compelling evidence that cutting taxes does little if anything to improve state economic performance.