BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Despite Flaws, Romney Proposal on Child Tax Credit Creates Opening for Bipartisan Action

The new proposal from Senators Mitt Romney, Richard Burr, and Steve Daines to expand the Child Tax Credit includes some important improvements to the credit compared to current law and may help create an opening for enacting a meaningful expansion this year, our new analysis explains.

The plan’s Child Tax Credit expansion on its own (excluding its problematic offsets, which target single parents with low incomes as discussed below) would lift 2.6 million children above the poverty line. This figure would climb to 4.1 million children if policymakers also made the credit fully refundable — that is, made the full credit available to children in families with low or no income — as an earlier proposal from Senator Romney would. (The American Rescue Plan made the credit fully refundable for 2021 only.)

Imposing an earnings test means that some children who need the credit the most will be left out or get only a partial credit. And it’s especially unfortunate because the plan doesn’t include some exemptions that have been widely discussed, such as for low-income parents with young children, parents with disabilities, and grandparents caring for their grandchildren.

That said, the Romney plan’s Child Tax Credit design is much better than current law. The plan would create a new, significantly improved structure for phasing in the credit as family earnings rise: families with one, two, or more children and with earnings of at least $10,000 (indexed for inflation) in the prior year would receive the full credit for each child, while families with earnings below $10,000 would receive a proportional credit. For example, a family earning $5,000 would receive 50 percent of the maximum credit for each child. The plan would also increase the maximum credit to $3,000 for school-age children and $4,200 for children under age 6.

To see the impact of this change, consider a single mother with children aged 4 and 7 who works part time around her children’s schedule as a cashier in a convenience store and makes $12,000. Under current law, her family receives a Child Tax Credit of $1,425 — effectively a partial credit for one child and no credit for the second child. Under the Romney plan’s phase-in structure, even excluding the plan’s increase in the maximum credit, the family would receive $4,000. (With the plan’s increase in the maximum credit, the family would receive $7,200.)

Or consider a family with $6,000 of earnings in a year and two school-age children, who also would significantly benefit from the phase-in structure of the Romney plan. Under current law, this family receives just $525. Under the Romney plan (including the increase in the maximum credit), the family would receive $1,800 per child — less than the maximum credit of $3,000, but a significant increase over current law.

But the plan has several problematic elements, most notably its offsets to pay for its Child Tax Credit improvements. The plan would have families with low incomes — especially single-parent families — pay for a major share of a proposal that should put top priority on boosting their incomes and that its sponsors describe as a major advance for families and children.

The plan would dramatically cut the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which boosts the incomes of workers with low and moderate incomes; the cut would be much larger for single-parent families than for married-couple families. The plan also would eliminate the “head of household” tax filing status, which millions of single parents who work at low-paying jobs use when they file their income tax returns. (The head-of-household filing status provides a standard deduction that’s larger than for single individuals without dependents but smaller than for married couples.)

The EITC and head-of-household changes cut in half, from 2.6 million to 1.3 million, the number of children whom the plan would lift above the poverty line. By comparison, simply making the current maximum credit of $2,000 per child available to all poor children would lift 1.7 million children above the poverty line.

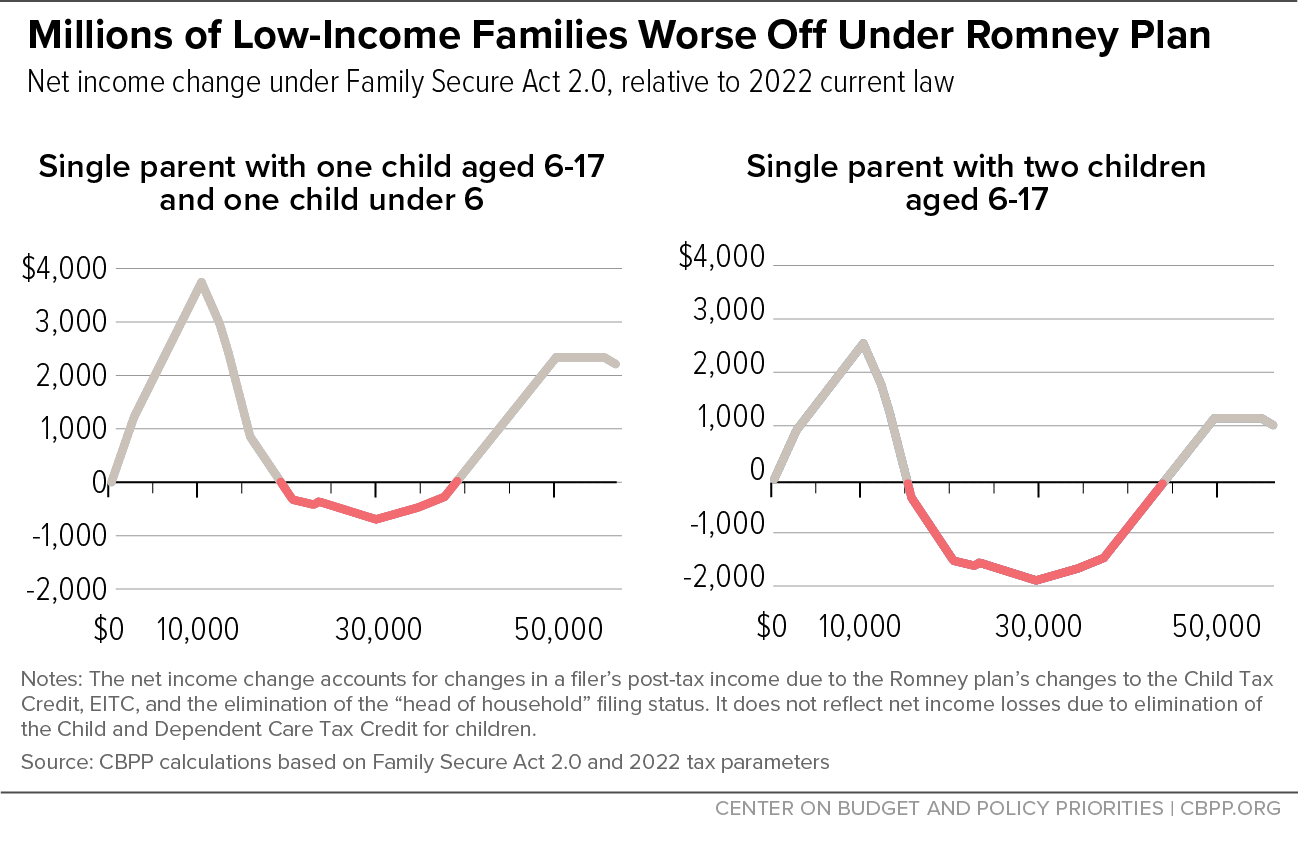

Because of those EITC and head-of-household changes, about 10 million children in families with incomes below $50,000 would see their family’s income cut under the Romney plan, despite the increase in their Child Tax Credit. For example, a single mother who has a daughter in fourth grade and a son in first grade and who makes $25,000 at a child care center would lose $1,665 under the Romney plan. A large majority of single parents with incomes between roughly $16,000 and $40,000 would have their incomes cut.

Even as the Romney plan would cut the incomes of millions of low- and moderate-income families, it would provide the full increase in the Child Tax Credit to married-couple families with incomes up to $400,000 and single-parent families with incomes up to $200,000. Some of these families would lose from the head-of-household change and the plan’s elimination of the non-refundable Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit for children, but many high-income married couples would benefit from the full increase in the maximum credit and face no offsetting tax increases.

In sum, the Romney plan falls short of providing full refundability for the Child Tax Credit, which should be the top priority in any expansion of the credit. Policymakers also should reject outright the plan’s offsets targeting single mothers, as well as a new restriction it would impose on families that include immigrants. (See our report for details.) But the Romney Child Tax Credit proposal itself, with its faster phase-in and higher maximum credit, is much better than current law and creates an opening for bipartisan action later this year, and our report explains how it could be improved in ways that could garner bipartisan support.