BEYOND THE NUMBERS

After Years of Underinvestment, It’s Time to Rebuild the Social Security Administration

President Biden’s 2022 budget includes a long-overdue boost in the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) operating budget to improve customer service, but the 10 percent increase is still less than the agency says it needs to do its job effectively. SSA Commissioner Andrew Saul, a Trump appointee, recommended a 12 percent increase for 2022. (Federal law requires the commissioner to submit a budget request to Congress alongside the President’s request.) When policymakers turn to 2022 appropriations to fund the government, they should give SSA enough funds to meet its daunting workload, which has become even more challenging during the COVID-19 crisis.

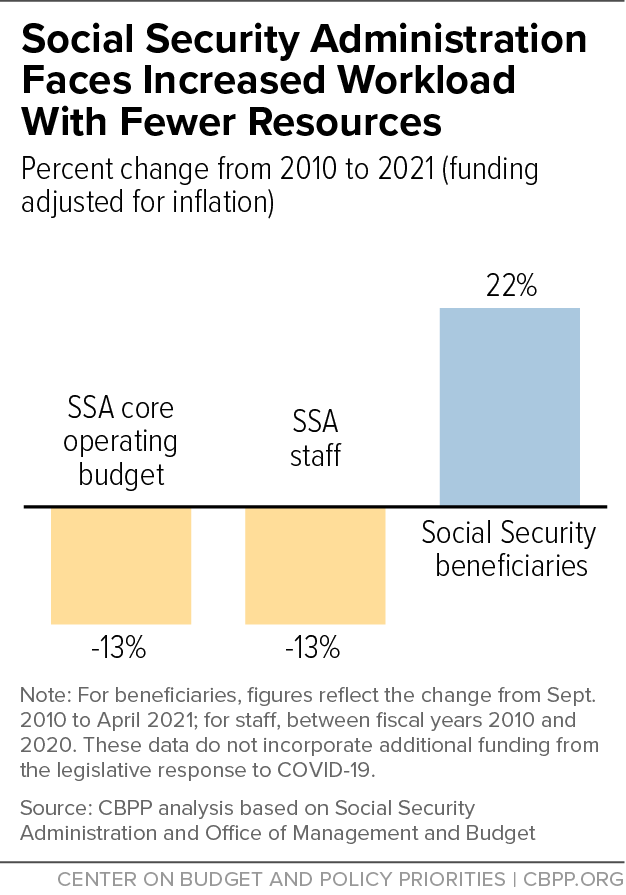

SSA customer service has suffered from over a decade of underinvestment. The agency’s operating budget fell 13 percent in inflation-adjusted terms from 2010 to 2021, even as the number of Social Security beneficiaries grew by 22 percent. Austere caps on discretionary funding contributed to the problem, but even when there was bipartisan agreement to raise the caps in 2020 and 2021, SSA’s operating budget didn’t keep up with inflation. Now that the caps have expired, policymakers should take the opportunity to rebuild critical government functions that have languished, like Social Security’s operations.

Budget cuts have hampered SSA’s ability to perform essential services such as determining eligibility in a timely manner for retirement, survivor, and disability benefits; paying benefits accurately and on time; responding to questions from the public; and updating benefits promptly when circumstances change. Since 2010, for example, SSA’s national 1-800 number staff shrank by 12 percent even as call volume grew 6 percent, resulting in more busy signals, more hang-ups, longer waits, and fewer calls answered, the SSA Inspector General found just before the pandemic. Busy rates tripled from 4.6 percent to 14.1 percent, while wait times increased six-fold from 3.4 to 20.4 minutes from 2010 to 2019.

The COVID-19 pandemic compounded the effects of long-term underinvestment in SSA. SSA closed its field offices to the public in March 2020 to protect its staff and its customers, who are largely elderly and disabled and at the highest risk of COVID-19 complications. Even now, field offices are only open on a very limited basis for in-person service, and the agency will need to take significant (and likely costly) precautions as it continues to reopen. SSA received supplemental funds to help support its short-term responses to the crisis, such as switching abruptly to teleservice and helping the IRS distribute economic impact (stimulus) payments, but that funding won’t be enough for the agency to deal with COVID-19’s longer-term fallout.

For example, applications for disability benefits have plummeted over the past year, especially among those who most need in-person assistance: people who are elderly, experiencing homelessness, or have limited English proficiency. SSA is starting more robust outreach to potential applicants but will need added funding to reach those left behind — before and during the pandemic. The President’s budget includes $75 million in new outreach funding for the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, which SSA administers.

Also, the long-term effects of COVID-19 will likely increase disability applications. COVID-19 has had disabling effects on many who contract it, including lung scarring, heart damage, and neurological and mental health effects. SSA will need to process these complicated new disability claims and any delayed claims from people who otherwise would have claimed in the past year.

Also, SSA already faces a backlog in appeals from people whose disability applications it denied, and the agency expects many more appeals stemming from the expected influx in applications. The President’s budget proposes to hire more staff to decide disability claims and appeals. It lays out a plan to increase the number of staff deciding initial claims by about 20 percent over the next two years, and sets a goal of eliminating the hearings backlog in 2022 and deciding future appeals promptly.

SSA has also been making necessary technological improvements to provide more options for applicants and beneficiaries (such as scheduling appointment online), update antiquated and inefficient IT systems, and improve payment accuracy. The President’s budget would invest an added $149 million in these long-term modernization projects.

During the pandemic, SSA necessarily suspended some non-essential work, like continuing disability reviews (CDRs) to determine whether disability beneficiaries are still eligible for benefits. But SSA must conduct CDRs on a certain schedule, so the agency — which reduced a previous CDR backlog before the pandemic using additional program integrity funding — now has a new backlog. The President’s budget requests $133 million in added funding for program integrity work.

By providing robust funding for essential SSA services in the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education appropriations bill for 2022, the President and Congress can make a down payment to rebuilding SSA and addressing new pandemic-related challenges.