Testimony of Michael Mitchell, Policy Analyst, Before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

End Notes

[1] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, April 2015.

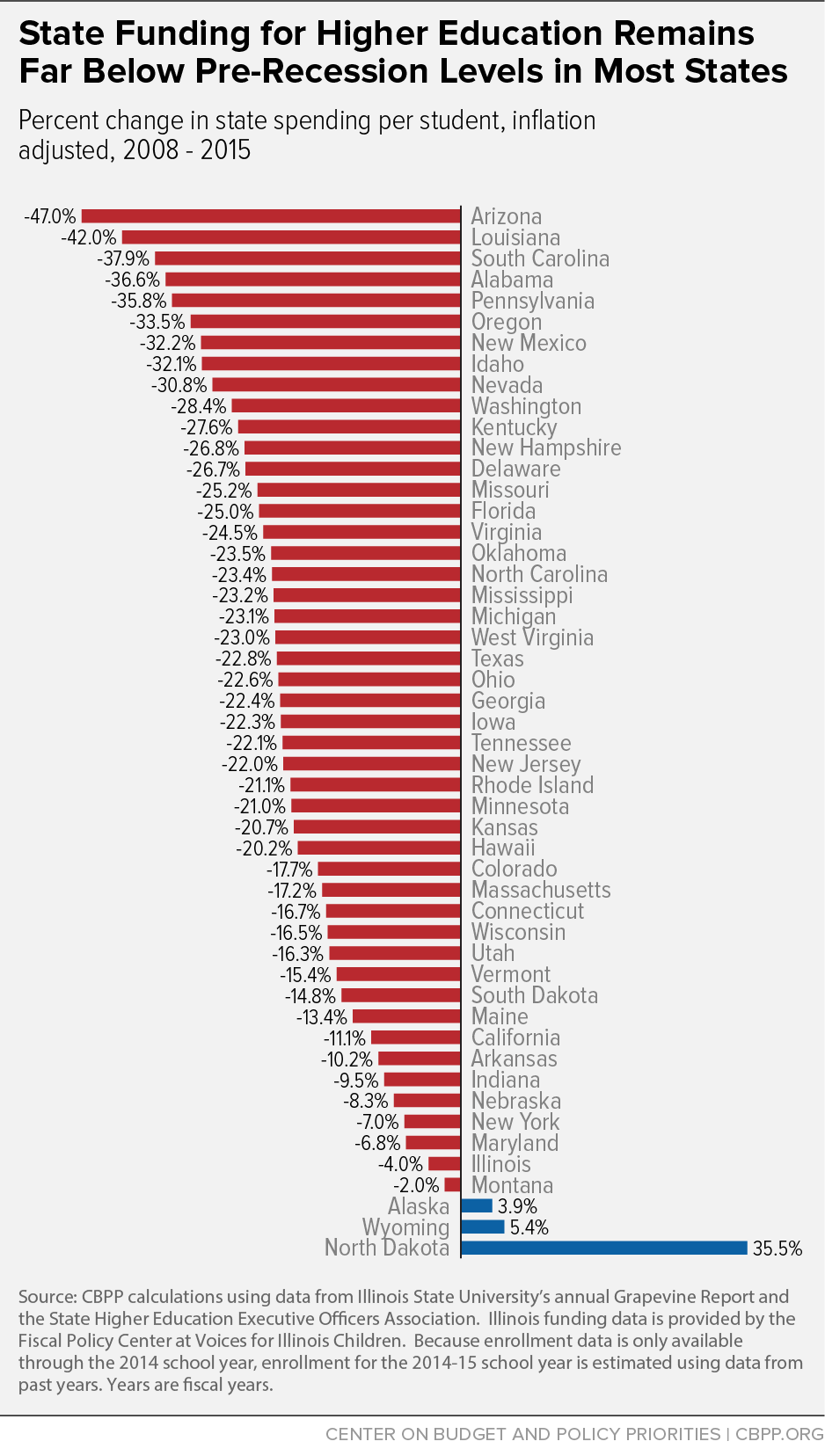

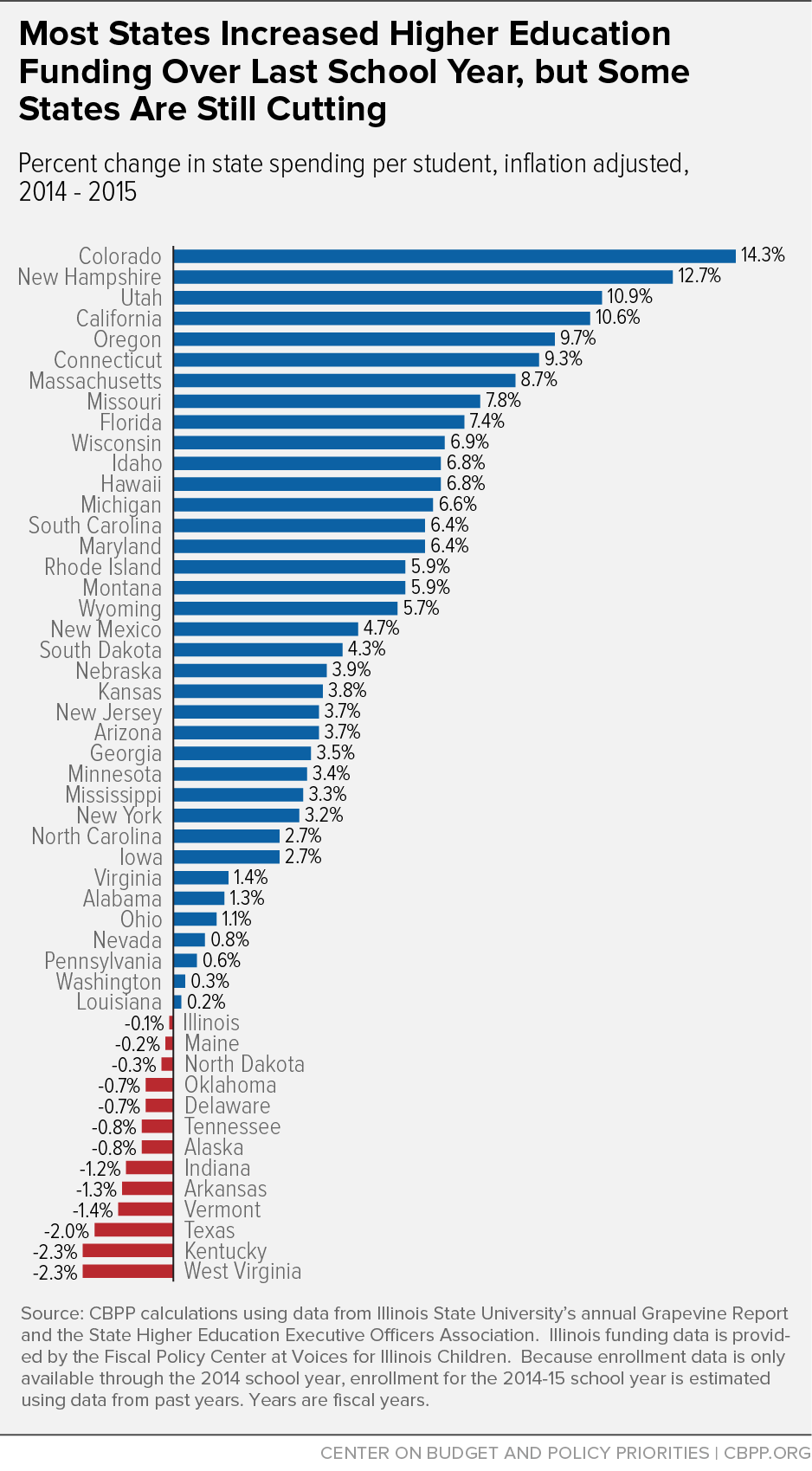

[2] CBPP calculation using the “Grapevine” higher education appropriations data from Illinois State University, enrollment and combined state and local funding data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, and the Consumer Price Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since enrollment data are only available through the 2012-13 school year, enrollment for the 2013-14 school year is estimated using data from past years.

[3] CBPP analysis of Census quarterly state and local tax revenue, http://www.census.gov/govs/qtax/.

[4] Nicholas Johnson, Phil Oliff, and Erica Williams, “An Update on State Budget Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 9, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/research/an-update-on-state-budget-cuts.

[5] CBPP calculation using the “Grapevine” higher education appropriations data from Illinois State University, enrollment and combined state and local funding data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, and the Consumer Price Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[6] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, April 2015. Note: while full-time-equivalent enrollment at public two- and four-year institutions is up since fiscal year 2008, between fiscal years 2012 and 2013 it fell by approximately 150,000 enrollees — a 1.3 percent decline.

[7] See, for example, “National Postsecondary Enrollment Trends: Before, During and After the Great Recession,” National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, July 2011, p. 6, http://pas.indiana.edu/pdf/National%20Postsecondary%20Enrollment%20Trends.pdf. A survey conducted by the American Association of Community Colleges indicated that increases in Fall 2009 enrollment at community colleges were, in part, due to workforce training opportunities; see Christopher M. Mullin, “Community College Enrollment Surge: An Analysis of Estimated Fall 2009 Headcount Enrollments at Community Colleges,” AACC, December 2009, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED511056.pdf.

[8] National Center for Education Statistics, Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by level and grade: Selected years, fall 1980 through fall 2023, Table 203.10, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_203.10.asp?current=yes.

[9] CBPP analysis of data from U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

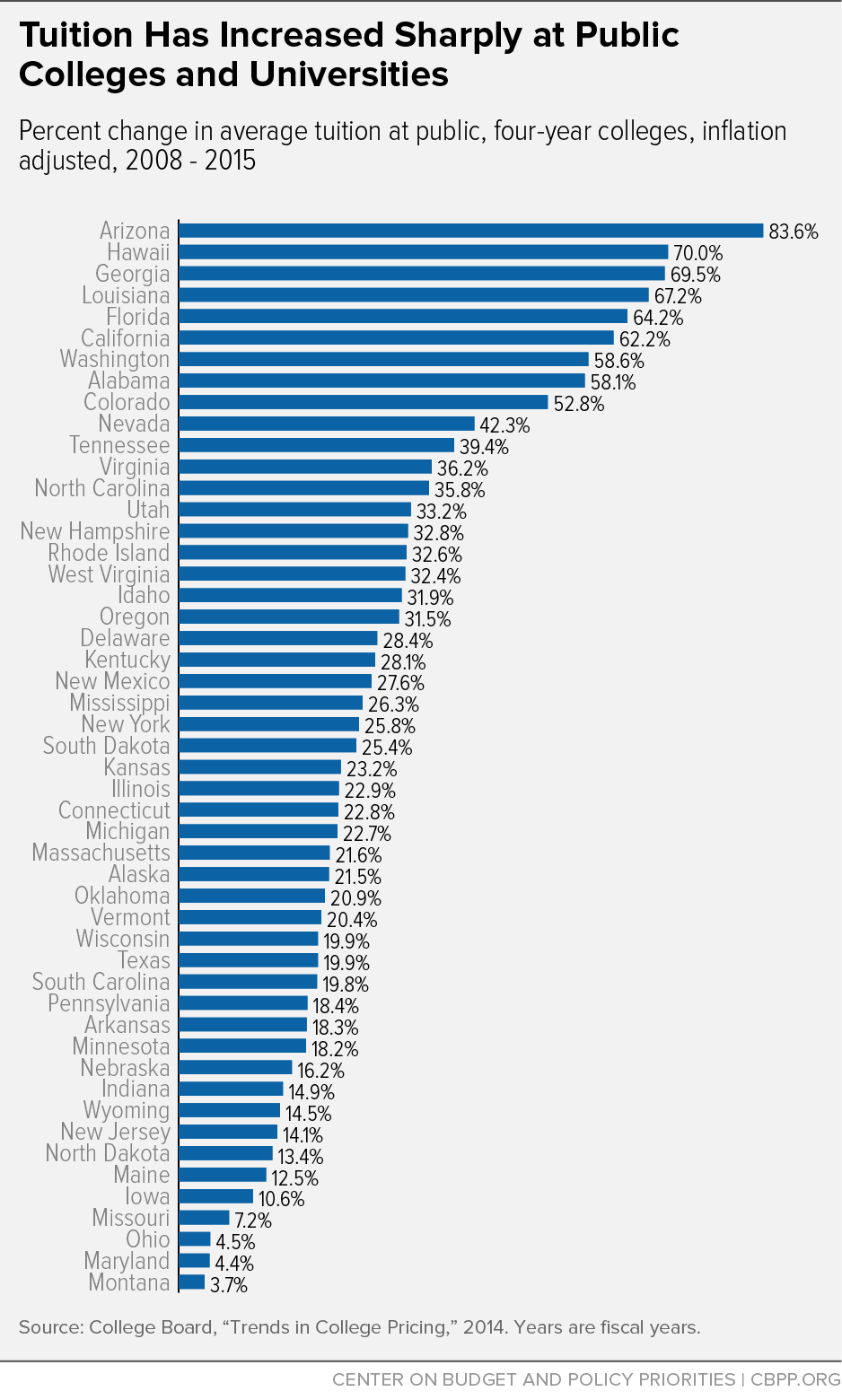

[10] CBPP analysis using the College Board’s “Trends in College Pricing 2014,” http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing/figures-tables/tuition-fees-room-board-time. Note: in non-inflation-adjusted terms, average tuition is up $2,948 over this time period.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Costs reported above include both published tuition and fees. Average tuition and fee prices are weighted by full-time enrollment.

[13] This paper uses CPI-U-RS inflation adjustments to measure real changes in costs. Over the past year the CPI-U-RS increased by 1.47 percent. We use the CPI-U-RS for the calendar year that begins the fiscal/academic year.

[14] CBPP calculation using the College Board’s “Trends in College Pricing 2013,” http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing. See appendix for fiscal year 2013-14 change in average tuition at public four-year colleges.

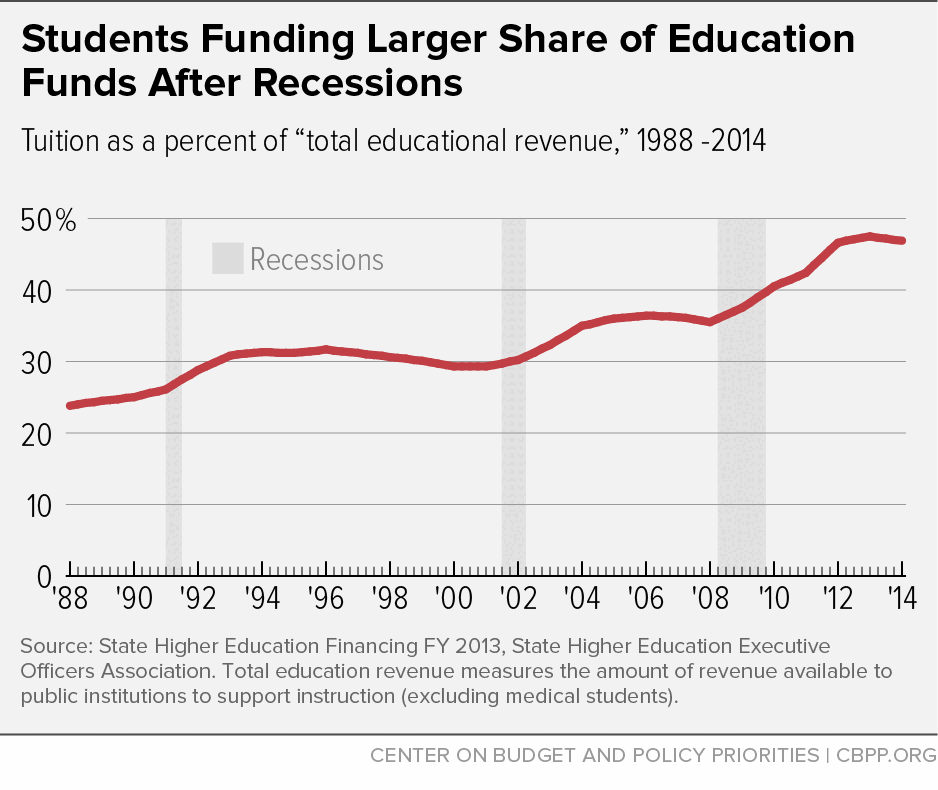

[15] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, “State Higher Education Finance: FY2013,” 2014, p. 22, Figure 4, http://www.sheeo.org/sites/default/files/publications/SHEF_FY13_04252014.pdf.

[16] State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, April 2015; government funding includes dollars from both state and local funding sources.

[17] See, for example, Steven W. Hemelt and Dave E. Marcotte, “The Impact of Tuition Increases on Enrollment at Public Colleges and Universities,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, September 2011; Donald E. Heller, “Student Price Response in Higher Education: An Update to Leslie and Brinkman,” The Journal of Higher Education, Volume 68, Number 6 (November-December 1997), pp. 624-659.

[18] Thomas J. Kane, “Rising Public College Tuition and College Entry: How Well Do Public Subsidies Promote Access to College?” National Bureau of Economic Research, 1995, http://www.nber.org/papers/w5164.pdf?new_window=1.

[19] Eric P. Bettinger et al., “The Role of Simplification and Information in College Decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA Experiment,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009, http://www.nber.org/papers/w15361.pdf.

[20] College Board, “Education Pays: 2013,” http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2013-full-report-022714.pdf.

[21] In a 2008 piece, Georgetown University scholar Anthony Carnavale pointed out that “among the most highly qualified students (the top testing 25 percent), the kids from the top socioeconomic group go to four-year colleges at almost twice the rate of equally qualified kids from the bottom socioeconomic quartile.” Anthony P. Carnavale, “A Real Analysis of Real Education,” Liberal Education, Fall 2008, p. 57.

[22] Christopher Avery and Caroline M. Hoxby, “The Missing ‘One Offs’: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low-Income Students,” National Bureau for Economic Research, Working Paper 18586, 2012, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/spring-2013/2013a_hoxby.pdf.

[23]Patrick T. Terenzini, Alberto F. Cabrera, and Elena M. Bernal, “Swimming Against the Tide,” College Board, 2001, http://www.collegeboard.com/research/pdf/rdreport200_3918.pdf.

[24] Eleanor W. Dillon and Jeffrey A. Smith, “The Determinants of Mismatch Between Students and Colleges,” National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19286. Additionally, other studies have found that undermatching is more likely to occur for students of color. In 2009 Bowen, Chingos, and McPherson found that undermatching was more prevalent for black students — especially black women — relative to comparable white students.

[25] Stacey Dale and Alan Krueger, “Estimating the Return to College Selectivity Over the Career Using Administrative Earning Data,” Mathematica Policy Research and Princeton University, February 2011, http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/PDFs/education/returntocollege.pdf.

[26] Christina Chang Wei, Laura Horn, and Thomas Weko, “A Profile of Successful Pell Grant Recipients: Time to Bachelor’s Degree and Early Graduate School Enrollment,” National Center for Education Statistics, July 2009, http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009156.pdf.

[27] See Susan Dynarski and Judith Scott-Clayton, “Financial Aid Policy: Lessons from Research,” The Future of Children, Spring 2013, http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/23_01_04.pdf.

[28] Brandon DeBot, “House Budget Would Reduce College Access by Cutting Pell Grants,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 25, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-budget-would-reduce-college-access-by-cutting-pell-grants.

[29] College Board, “Cumulative Debt of 2011-12 Bachelor’s Degree Recipients by Dependency Status and Family Income,” October 2014, http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing/figures-tables/net-prices-income-over-time-public-sector.

[30] College Board, “Trends in Student Aid, 2014: Median Debt Levels of 2007-08 Bachelor’s Degree Recipients by Income Level,” October 2014, Figure 2010_9, http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2014-trends-student-aid-final-web.pdf. Low-income dependent students are defined as students from families earning less than $30,000 annually, while high-income students come from families earning more than $106,000.

[31] The Institute for College Access and Success, “Pell Grants Help Keep College Affordable for Millions of Americans,” March 13, 2015, http://ticas.org/sites/default/files/pub_files/overall_pell_one-pager.pdf.

[32] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit,” February 2015, http://www.newyorkfed.org/householdcredit/2014-q4/data/pdf/HHDC_2014Q4.pdf.

[33] College Board “Trends in Student Aid,” Figure 13A, http://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid/figures-tables/average-cumulative-debt-bachelors-recipients-public-four-year-time.

[34] Brandon DeBot, “House Budget Would Reduce College Access by Cutting Pell Grants,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 25, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-budget-would-reduce-college-access-by-cutting-pell-grants.

[35] David Reich “Sequestration and Its Impact on Non-Defense Appropriations,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 19, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/sequestration-and-its-impact-on-non-defense-appropriations.

[36] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon DeBot, “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 3, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/eitc-and-child-tax-credit-promote-work-reduce-poverty-and-support-childrens-development?fa=view&id=3793.