Tapping More People’s Capacity to Innovate Can Help States Thrive

End Notes

[1] Alex Bell et al., “Who Becomes an Inventor in America? The Importance of Exposure to Innovation,” Opportunity Insights, revised November 2018, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/losteinsteins/2018. Harvard economist Raj Chetty is among the authors in this and other Opportunity Insights research.

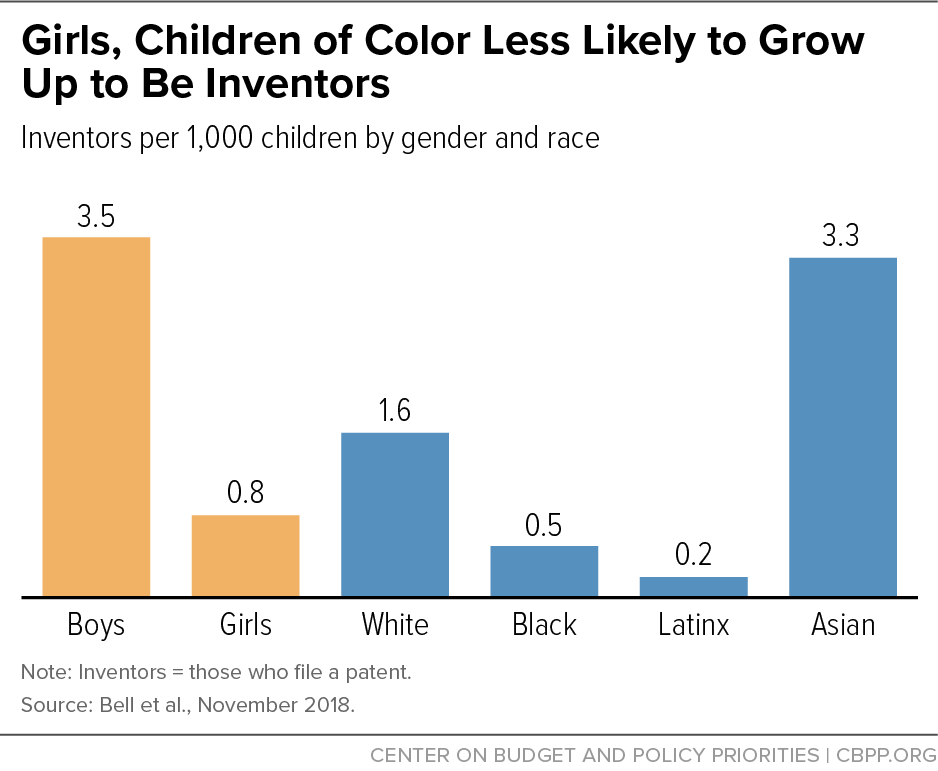

[2] The Lost Einsteins analysis includes estimates of invention levels by race, gender, and family income, though publicly available data do not allow replication of the combined racial, gender, and income calculation at the state level. Nonetheless, because people of color are overrepresented at lower levels of wealth and income, eliminating income disparities in innovation would inherently provide them disproportionate gains.

[3] For example, the creation of assembly line production cut the time to produce the Model T Ford by 68 percent over six years. More recently, information technology transformed the way companies produce and sell their goods and services, while tapping new markets and new business models. Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney, “A Dozen Economic Facts About Innovation,” Hamilton Project, August 5, 2011, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/a_dozen_economic_facts_about_innovation.

[4] Audre Biciunaite, “Economic Growth and Life Expectancy — Do Wealthier Countries Live Longer?” Euromonitor International, March 14, 2014, https://blog.euromonitor.com/economic-growth-and-life-expectancy-do-wealthier-countries-live-longer/.

[5] Not all innovations are beneficial to human well-being, and even generally positive innovations can lead to substantial negative spillover effects, for example, advances in weaponry and chemical development, and the cotton gin which played a pivotal role in the United States’ westward expansion of slavery. Innovations such as fossil fuel extraction or tobacco cultivation may have bolstered economic growth but also caused critical harm to the environment and public health. Creative destruction is therefore a necessary but insufficient component of human progress — it must be accompanied by policies and value systems that enhance fairness, health, and overall well-being.

[6] See, for example, Charles I. Jones, “Sources of U.S. Economic Growth in a World of Ideas,” American Economic Review, Vol. 92, No. 1, 2002: 220-239; and Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction,” Econometrica, Vol. 60, No. 2, 1992: 323-351.

[7] Both the Lost Einsteins work and some other research in the field characterizes “star inventors” as those in the top 5 percent of the distribution when it comes to patent citations. Citations are widely used as a measure of a patent’s scientific or economic impact, because they show the extent to which additional, later inventions in a field are building on that prior breakthrough.

[8] As the Opportunity Insights team describes, “Scientific progress is largely driven by a few star inventors who are highly compensated for their work by the market.” Their data indicate that only about 1 out of every 10,000 children grow up to reach the star inventor threshold, compared to 22 out of every 10,000 children who become inventors generally.

[9] Researchers often define “gazelle” firms as those that produce average annual job growth of at least 20 to 25 percent. Michael Mazerov and Michael Leachman, “State Job Creation Strategies Often Off Base,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 3, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-job-creation-strategies-often-off-base.

[10] See, for example, Ryan A. Decker et al., “Where Has All The Skewness Gone? The Decline In High-Growth (Young) Firms In The U.S.,” NBER Working Paper No. 21776, January 2016, https://www.nber.org/papers/w21776; and Michael Mandel, “A Historical Perspective on Tech Job Growth,” Progressive Policy Institute, January 10, 2017, https://www.progressivepolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/tech-job-boom-1-12c-17-formatted.pdf.

[11] Jonathan Rothwell et al., “Patenting Prosperity: Invention and Economic Performance in the United States and its Metropolitan Areas,” Brookings Institution, February 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/patenting-prosperity-rothwell.pdf.

[12] Ufuk Akcigit, John Grigsby, and Tom Nicholas, “The Rise of American Ingenuity: Innovation and Inventors of the Golden Age,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 17-063, 2017, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=52130.

[13] The same analysis estimated that a low-patenting metro area could gain $4,300 more per worker over a decade if it became a high-patenting metro area. See Rothwell et al., pp. 17-19.

[14] See, for example, Mark Muro and Robert Maxim, “Big tech’s role in regional inequality,” Brookings Institution, October 9, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/10/09/big-techs-role-in-regional-inequality/; and Jonathan Rothwell, “Regional Inequality and ‘The New Geography of Jobs,’” Brookings Institution, August 7, 2012, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2012/08/07/regional-inequality-and-the-new-geography-of-jobs/.

[15] Atul Gawande, “Why Americans Are Dying from Despair,” New Yorker, March 16, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/03/23/why-americans-are-dying-from-despair.

[16] See, for example, Darrell M. West, “How the innovation economy leads to growth,” Brookings Institution, April 25, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/how-the-innovation-economy-leads-to-growth/; and Bruce Katz and Julie Wagner, “The Rise of Innovation Districts,” May 2014, Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/essay/rise-of-innovation-districts/.

[17] Nicholas Bloom, John Van Reenen, and Heidi Williams, “A Toolkit of Policies to Promote Innovation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2019, pp. 163–184, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.33.3.163.

[18] Lisa D. Cook, “Policies to Broaden Participation in the Innovation Process,” Hamilton Project, August 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Cook_PP_LO_8.13.pdf.

[19] For a concise overview of how recent improvements in data and methods are allowing for a more sophisticated analysis of innovation, see pp. 4-6 of Alex Bell et al., “Do Tax Cuts Produce More Einsteins? The Impacts of Financial Incentives vs. Exposure to Innovation on the Supply of Inventors,” Opportunity Insights, January 2019, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/do-tax-cuts-produce-more-einsteins-the-impacts-of-financial-incentives-vs-exposure-to-innovation-on-the-supply-of-inventors/.

[20] Bell et al., 2018. As noted, Chetty is among the authors in this and other Opportunity Insights research.

[21] For concise overviews of the Lost Einsteins study and its implications, see Matthew Yglesias, “Groundbreaking empirical research shows where innovation really comes from,” Vox, updated December 5, 2017, https://www.vox.com/2017/12/4/16706352/innovation-inequality-race-gender; and Alana Semuels, “America’s Lost Einsteins,” Atlantic, December 4, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/12/innovation-income-chetty/547202/.

[22] See, for example, Gerald Carlino and William R. Kerr, “Agglomeration and Innovation,” NBER Working Paper No. 20367, 2014, https://www.nber.org/papers/w20367.pdf; and Aaron Chatterji, Edward L. Glaeser, and William R. Kerr, “Clusters of Entrepreneurship and Innovation,” NBER Working Paper No. 19013, 2013, https://www.nber.org/papers/w19013.

[23] Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas, pp. 10-13.

[24] In 1975 almost half of all counties had no patent activity at all, and today patenting is highly concentrated in metropolitan areas and near research universities. Ryan Nunn, Jana Parsons, and Jay Shambaugh, “The Geography of Prosperity,” Brookings Institution, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/PBP_FramingChapter_compressed_0928.pdf.

[25] Rothwell et al., 2013.

[26] Ibid. Another 25 percent of metro area patents during that span were in an area with at least one science program (not top-ranked), while just 14 percent came from metro areas with zero doctoral programs in science — a group that contains 27 percent of the metropolitan population.

[27] Kristy Buzard and Gerald A. Carlino, “The Geography of Research and Development Activity in the U.S.,” FRB of Philadelphia Working Paper No. 09-16, August 12, 2009, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1448025.

[28] An estimated 59 percent of inventors between 1880 and 1940 were interstate migrants, according to one study, compared to 43 percent of the total population. States most likely to receive new inventors were those with higher levels of population density or a well-established financial sector, such as California and New York. Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas, p. 9.

[29] As one study focused on research and development dollars describes, “A high geographic concentration of R&D labs creates an environment in which ideas move quickly from person to person and from lab to lab. Locations that are dense in R&D activity encourage knowledge spillovers, thus facilitating the exchange of ideas that underlies the creation of new goods and new ways of producing existing goods” (emphasis added). Buzard and Carlino.

Another study focused on African American inventors highlights the importance of social capital in fostering innovation, namely that inventors tend to be most prolific in settings where they can develop social ties to fellow inventors and readily share ideas through venues such as civic organizations or professional networks. Lisa D. Cook, “Inventing Social Capital: Evidence From African American Inventors, 1843-1930,” Michigan State University, May 2011, https://msu.edu/~lisacook/pats_great_paper_0511_final.pdf.

[30] Endeavor Insight, “What Do the Best Entrepreneurs Want in a City? Lessons from the Founders of America’s Fastest Growing Companies,” February 2014, p. 6, https://issuu.com/endeavorglobal1/docs/what_do_the_best_entrepreneurs_want.

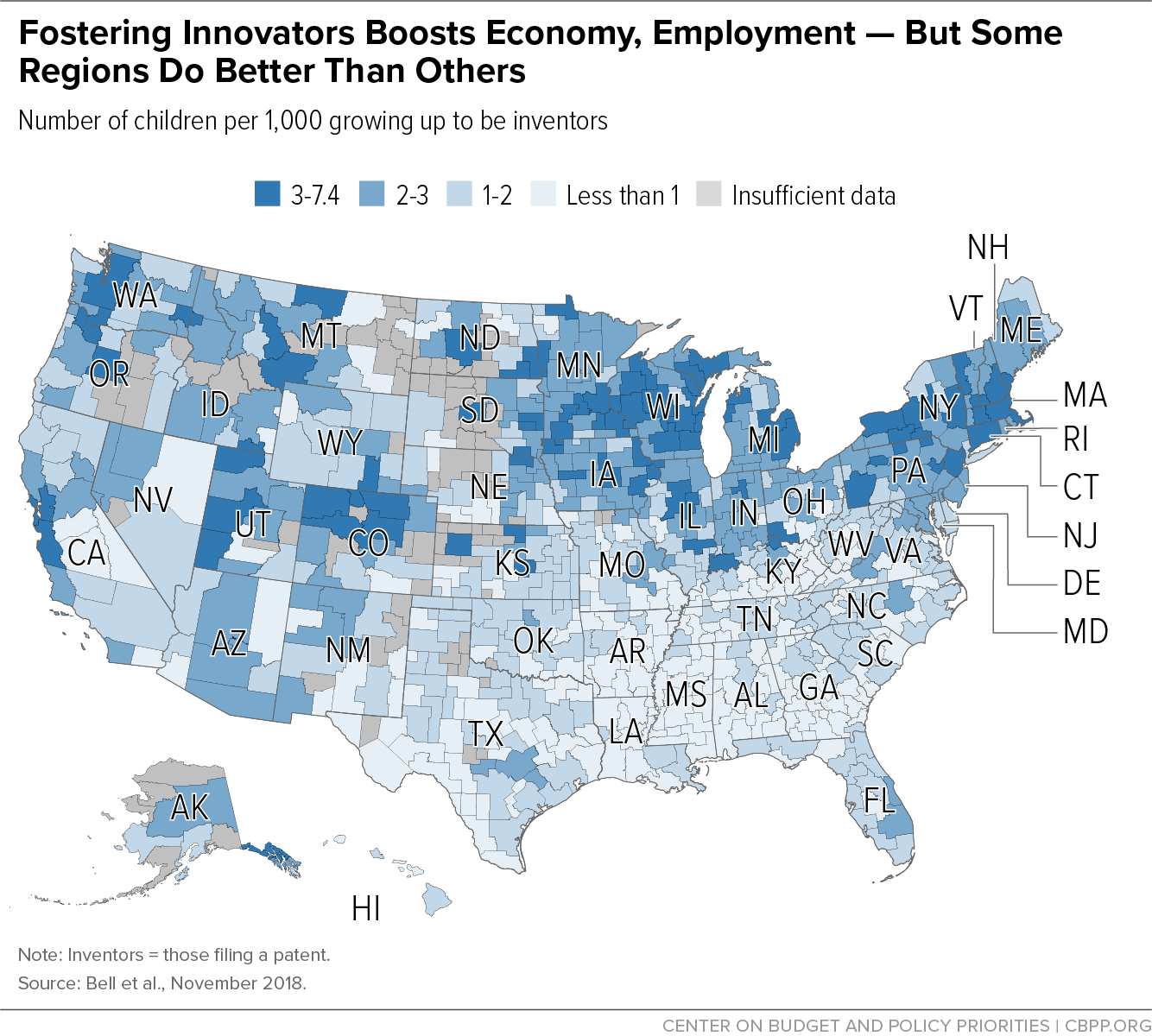

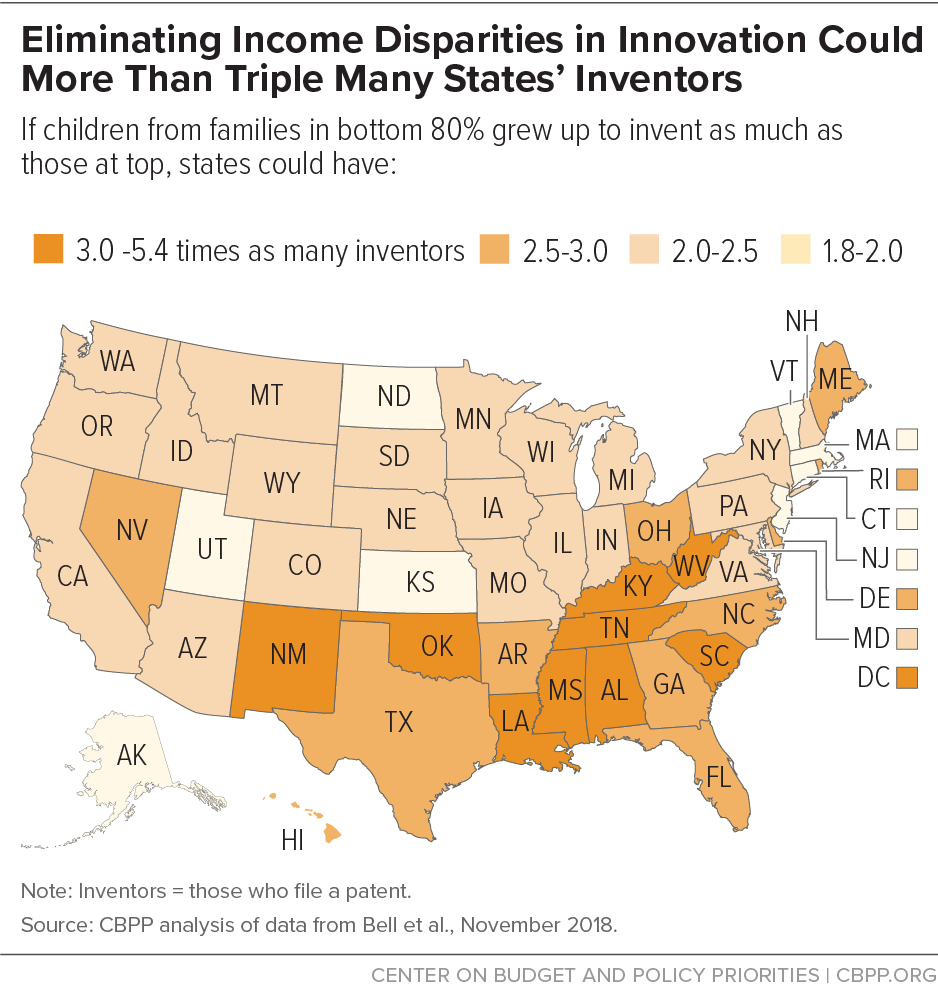

[31] CBPP analysis of data from Opportunity Insights, available at https://opportunityinsights.org/data/?geographic_level=0&topic=0&paper_id=520#resource-listing.

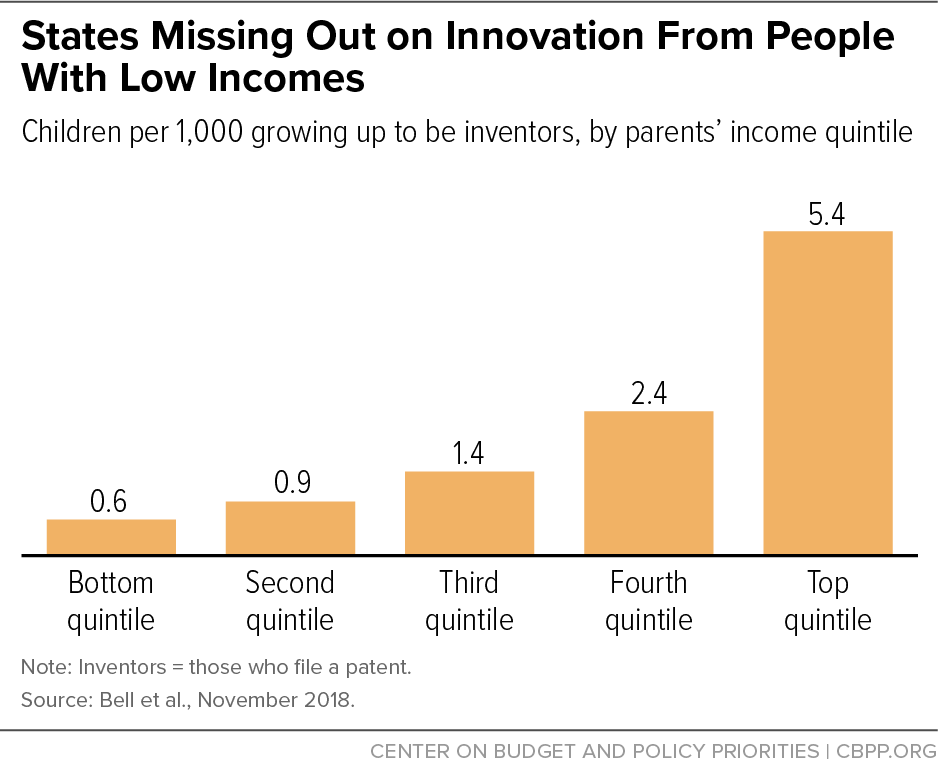

[32] As the authors describe it, “Low-income children start out on relatively even footing with their higher-income peers in terms of innovation ability, but fall behind over time, perhaps because of differences in their childhood environment.” This finding is mirrored by prior research in the field indicating that low-income children struggle to reach their full economic potential due to systemic barriers, even when they stand out as high achievers in school or early in their careers.

[33] One widely cited 2017 study of patenting and family income in Finland found that people with fathers at the very top of the income distribution were about ten times likelier to become inventors than people with fathers from the bottom of the income distribution, but that this effect fell by about two-thirds once controlling for IQ and parents’ educational level. The authors contend that a large portion of the observed income effect may be explained by an indirect benefit of additional education, in that more educated people also tend to have higher incomes as adults. Philippe Aghion et al., “The Social Origins of Inventors,” NBER Working Paper No. 24110, December 2017, https://www.nber.org/papers/w24110.

Also, a 2015 study looking at U.S. census data back to 1930 found that people from richer backgrounds are more likely to become inventors, whereas those from simply more educated backgrounds are not. Murat Alp Celik, “Does the Cream Always Rise to the Top? The Misallocation of Talent in Innovation,” University of Pennsylvania, August 2015, https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/filevault/event_papers/Celik_JMP.pdf

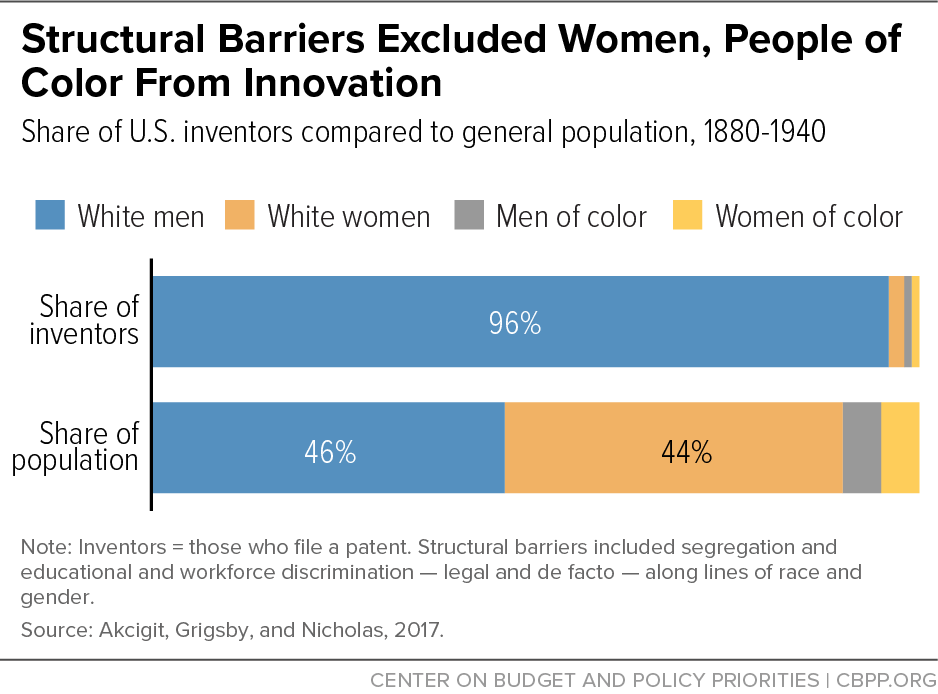

[34] Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas, p. 9. It is worth noting that analyses of historical patent data are limited by the fact that not all inventions reach the final stage of filing a formal patent, due to factors including explicit racial or gender discrimination and lack of resources. For example, one study details the struggles that African Americans faced in accessing the formal patent system, especially when living in places marked by high levels of legal segregation, and describes evidence that some Black inventors sought to disguise their racial identity in order to see their ideas come to fruition or avoid negative repercussions. See Cook, 2011.

[35] B. Zorina Khan and Kenneth L. Sokoloff, “Institutions and Democratic Invention in 19th-Century America: Evidence from ‘Great Inventors,’ 1790-1930,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 2, May 2014. As cited in Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas.

[36] A new study posits that much of the racial disparity was driven by oppressive institutions in the South, and that Black Americans living outside that region invented nearly as frequently as white Americans, relative to their share of the population. Jonathan Rothwell, Andre M. Perry, and Mike Andrews, “The Black innovators who elevated the United States: Reassessing the Golden Age of Invention,” Brookings Institution, November 23, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-black-innovators-who-elevated-the-united-states-reassessing-the-golden-age-of-invention/?.

[37] See, for example, Susan Dominus, “Women Scientists Were Written Out of History. It’s Margaret Rossiter’s Lifelong Mission to Fix That,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/unheralded-women-scientists-finally-getting-their-due-180973082/.

[38] Although Asian American children grow up to invent at significantly higher rates than all other racial and ethnic groups in the Einsteins study, national research consistently points to sizable disparities within this racial category, which aggregate estimates often mask. For example, a 2016 analysis from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth notes that while 51 percent of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders had a bachelor’s degree or higher at the time — an average share well above white Americans — that fact hid sizable differences among various subgroups. For example, rates ranged from highs of about 75 percent for Taiwanese and 73 percent for Indians to lows below 20 percent for groups such as Cambodians, Hmong, and Laotians. See “How data disaggregation matters for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders,” Washington Center for Economic Growth, December 2016, https://equitablegrowth.org/how-data-disaggregation-matters-for-asian-americans-and-pacific-islanders/.

[39] Bell et al., 2018.

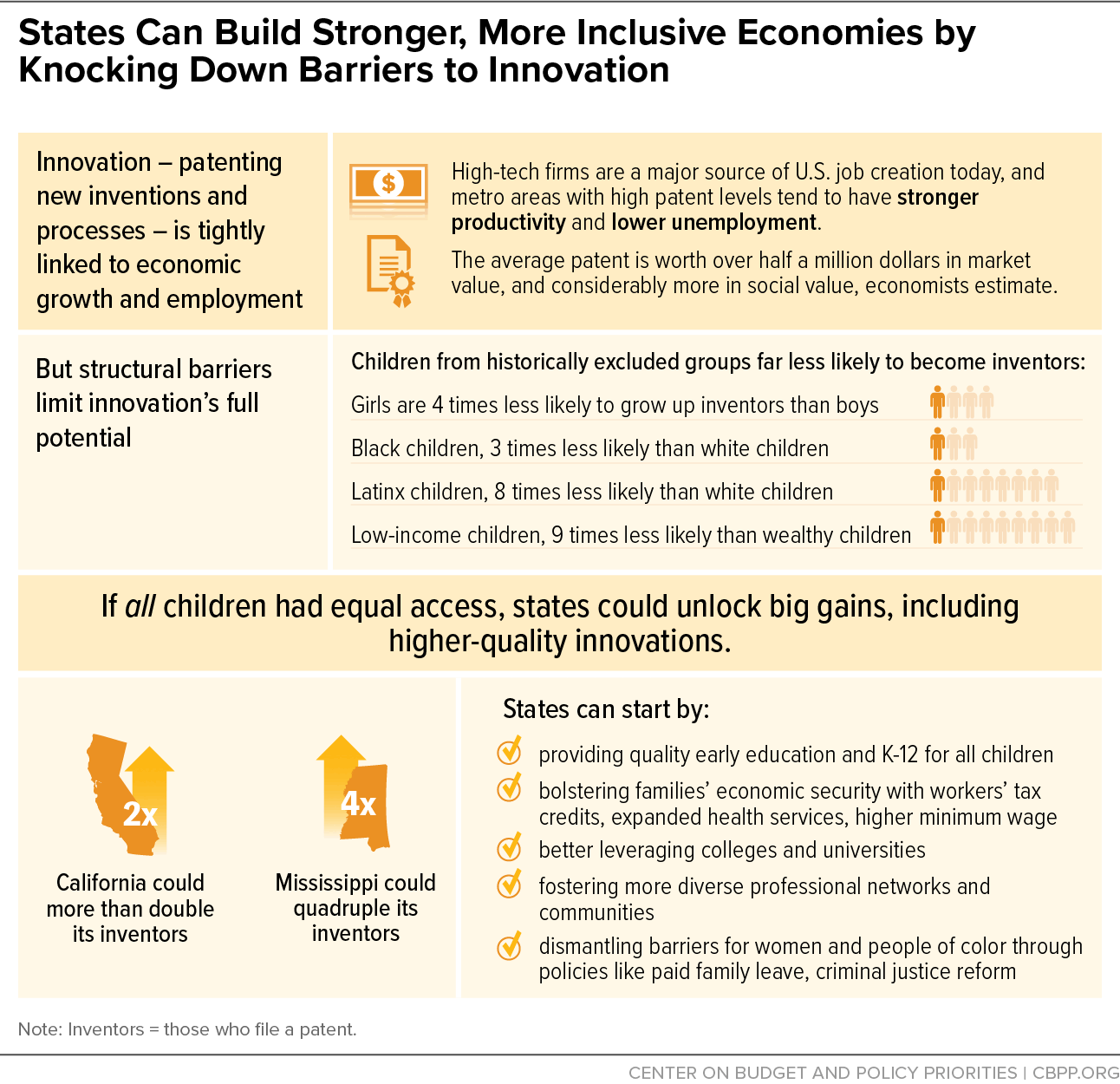

[40] The Lost Einsteins study includes estimates of potential inventor gains from eliminating disparities by race, gender, and family income. Due to various constraints of the publicly available data, we choose to only replicate the income piece of the calculation at the state level. Their analysis estimates that the national effect of equalizing invention rates for poor children, women, and people of color would be four times as many inventors. Our state-level analysis finds that achieving that end for non-rich children (regardless of race or gender) would boost the number of inventors by 2.4 times, so about 60 percent of the estimated nationwide increase.

[41] The extent to which diversifying the field of innovation would lead to more breakthroughs, and hence stronger economic growth, is a question of some debate. On one hand, attracting new entrants could expand the overall quantity of economic innovation, if new innovators bring new ideas and products that would have otherwise not been created. On the other hand, it is possible that innovation more closely resembles a zero-sum game, where additional innovation by people newly enticed into the field simply replaces innovation that would’ve already taken place, perhaps in another time or place. In that scenario, breaking down barriers for women, people of color, and low-income families would still have worthwhile benefits for economic equity, but wouldn’t necessarily enhance overall growth. Though even in this case, it would likely help a state or country grow more economically competitive relative to its rivals, both by tapping a broader pool of human talent and providing a more attractive locale for a diverse array of groups.

[42] As the Opportunity Insights team describes, “We caution … that this finding does not necessarily imply that aggregate welfare would be higher if these individuals were to enter innovation, as they might currently be pursuing other careers that also have substantial social returns.” Bell et al., 2018, p. 5.

[43] See Chang-Tai Hsieh et al., “The Allocation of Talent and U.S. Economic Growth,” University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2019-93, June 18, 2019, pp. 29 and 33, https://bfi.uchicago.edu/working-paper/the-allocation-of-talent-and-u-s-economic-growth/.

[44] Jennifer Hunt et al., “Why Don’t Women Patent?” NBER Working Paper No. 17888, March 2012, https://www.nber.org/papers/w17888?ntw.

[45] Cook, 2020.

[46] See James Heckman, “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children,” Science, June 2006, http://jenni.uchicago.edu/papers/Heckman_Science_v312_2006.pdf; and Timothy J. Bartik, “Investing in Kids: Early Childhood Programs and Local Economic Development,” W.E. Upjohn Institute, 2011, https://research.upjohn.org/up_press/207/ .

[47] Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, “Does Diversity Actually Increase Creativity?” Harvard Business Review, June 28, 2017.

[48] Richard B. Freeman and Wei Huang, “Collaborating with People Like Me: Ethnic Coauthorship within the United States,” Journal of Labor Economics, July 2014, https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/20453995.

[49] “Interactions among inventors are strongly correlated with higher subsequent inventor productivity (i.e., inventor innovation quality), even after including several detailed controls, such as inventor fixed effects. Inventors learn from each other to produce better innovations.” And, “We find that interactions are crucial in explaining individual productivity and aggregate growth.” Ufuk Akcigit et al., “Dancing with the Stars: Innovation Through Interactions,” NBER Working Paper No. 24466, March 2018, https://www.nber.org/papers/w24466.

[50] Cristina Díaz-García, Angela González-Moreno, and Francisco Jose Sáez-Martínez, “Gender diversity within R&D teams: Its impact on radicalness of innovation,” Innovation, December 2014, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.5172/impp.2013.15.2.149.

[51] Jennifer Schmidt et al., “The Edge Effect,” NPR: Hidden Brain, July 2, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/07/02/625426015/the-edge-effect. These creative benefits are strongest in cases where people have a deep, ongoing relationship with those from other backgrounds, such as dating, working together in close proximity, or growing up in the same neighborhood, rather than just occasional contact. For further reading, see Jackson G. Lu et al., “‘Going Out’ of the Box: Close Intercultural Friendships and Romantic Relationships Spark Creativity, Workplace Innovation, and Entrepreneurship,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 102, No. 7, 2017, https://bit.ly/2J0cIZW.

[52] Richard Florida, “The Particular Creativity of Dense Urban Neighborhoods,” CityLab, November 2019, https://www.citylab.com/life/2019/11/neighborhood-population-density-cities-innovation-creativity/601258/.

[53] Case in point, an estimated 93 percent of the world’s recent patent applications were filed by inventors living in metropolitan areas with just 23 percent of the world’s population. Jonathan Rothwell, “Global Innovation: The Metropolitan Edition,” New Republic, March 16, 2012, https://newrepublic.com/article/101780/global-innovation-the-metropolitan-edition.

[54] Douglas Medin, Carol D. Lee, and Megan Bang, “Point of View Affects How Science Is Done,” Scientific American, October 1, 2014, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/point-of-view-affects-how-science-is-done/.

[55] For example, a 2011 study found that among applicants to National Institutes of Health (NIH) project grants, only 1.5 percent self-identified as African American or Black and only 3.3 percent as Hispanic. Yet these groups are also significantly more likely than white Americans to report poor health outcomes, and infant mortality rates are more than twice as high for Black mothers (11.4 deaths per 1,000 births) than white mothers (4.9 deaths). National Institutes of Health, “NIH-commissioned study identifies gaps in NIH funding success rates for Black researchers,” August 18, 2011, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-commissioned-study-identifies-gaps-nih-funding-success-rates-black-researchers. For more on this topic, see Jennifer Sullivan, “Better State Budget, Policy Decisions Can Improve Health,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 21, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/better-state-budget-policy-decisions-can-improve-health.

[56] Angela Glover Blackwell, “The Curb-Cut Effect,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2017, https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_curb_cut_effect.

[57] Caroline M. Hoxby and Christopher Avery, “The Missing ‘One-Offs’: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low Income Students,” NBER Working Paper No. 18586, December 2012, pp. 24-27, https://www.nber.org/papers/w18586.

[58] Exposure effects also vary by geography and type of invention; for instance, a child who grew up in Silicon Valley or whose parents or neighbors invented in computer programming is likely to become a tech-based inventor as well, rather than innovating in some other field. This helps explain why some areas of the country have carved out niches when it comes to innovation, as well as children’s likelihood to invent in specific fields, such as medical devices in Minneapolis or automobile advancements in Detroit.

[59] Hua-Yu Sebastian Cherng and Peter F. Halpin, “The Importance of Minority Teachers: Student Perceptions of Minority Versus White Teachers,” Educational Researcher, Vol. 45, No. 7, pp. 407–420, October 1, 2016, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.3102/0013189X16671718. On teacher expectations, see Seth Gershenson, Stephen B. Holt, and Nicholas W. Papageorge, “Who Believes in Me? The Effect of Student-Teacher Demographic Match on Teacher Expectations,” Upjohn Institute Working Paper 15-231, 2015, https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1248&context=up_workingpapers.

[60] Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas.

[61] For a detailed analysis of how state tax and budget policies have contributed to structural racism, see Michael Leachman et al., “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/advancing-racial-equity-with-state-tax-policy.

[62] See, for example, Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, Harvard University Press, 2016; Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, New Press, 2010; and Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Liveright, 2017.

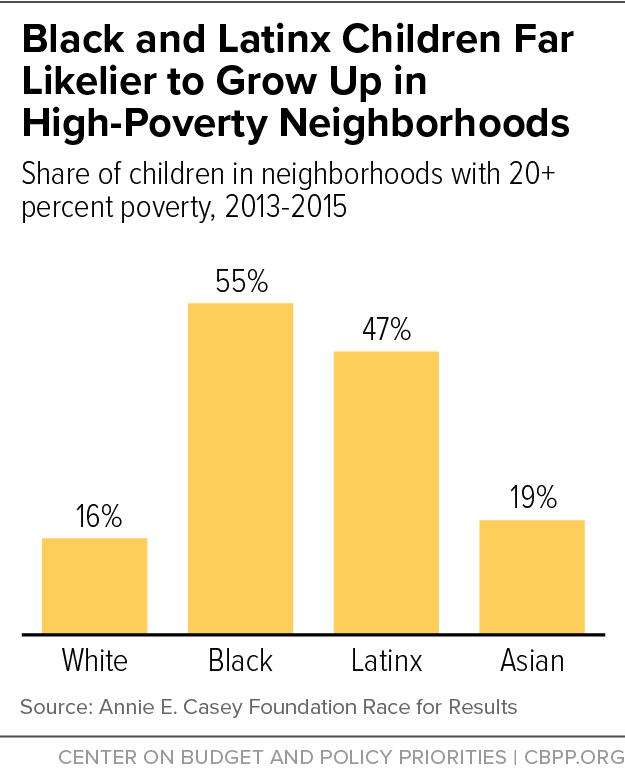

[63] Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Kids of Color More Likely to Live in High-Poverty Neighborhoods Now Than During Great Recession,” May 10, 2018, https://www.aecf.org/blog/kids-of-color-more-likely-to-live-in-high-poverty-neighborhoods-now/.

[64] K.A. Kilday, “How Does Toxic Stress Affect Low-Income and Black Children?” CityLab, May 8 2019, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2019/05/children-stress-neighborhoods-health-wellness-parent-study/589027/.

[65] Michael Mitchell et al., “State Higher Education Funding Cuts Have Pushed Costs to Students, Worsened Inequality,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 24, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-higher-education-funding-cuts-have-pushed-costs-to-students.

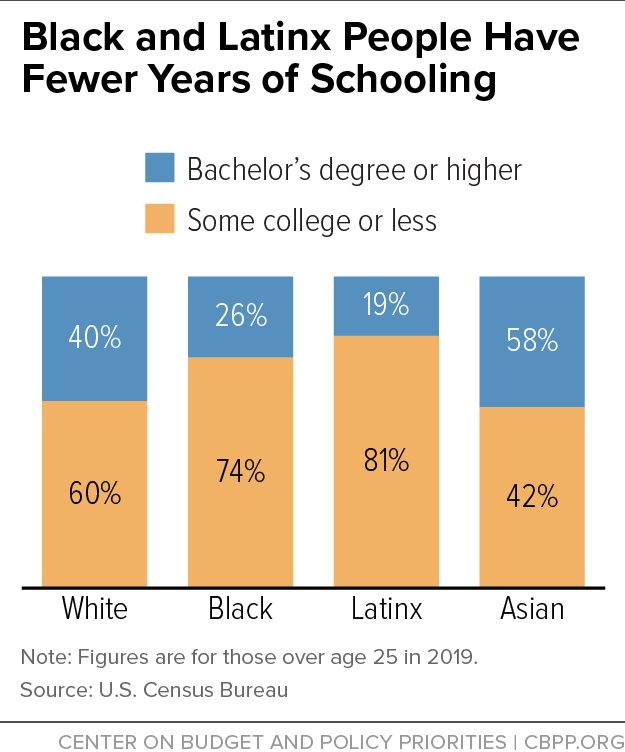

[66] Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas, p. 18. That analysis — which focused on historical innovation from 1880 to 1940 — found that people with a college degree were four times likelier to become an inventor than those with a high school diploma; an estimated 40 percent of inventors in 1940 had a college degree, versus only 10 percent of the non-inventor population.

[67] See, for example, Jonathan Rothwell, “Black Students at Top Colleges: Exceptions, Not the Rule,” Brookings Institution, February 3, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/social-mobility-memos/2015/02/03/black-students-at-top-colleges-exceptions-not-the-rule/.

[68] See United States v. Fordice, 505 U.S. 717, decided June 1992, and Debbie Elliott, “Integrating Ole Miss: A Transformative, Deadly Riot,” NPR, October 1, 2012, https://www.npr.org/2012/10/01/161573289/integrating-ole-miss-a-transformative-deadly-riot.

[69] See Jayne O’Donnell and David Robinson, “After decades of effort, African-American enrollment in medical school still lags,” USA Today, February 28, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2019/02/28/medical-school-student-african-american-enrollment-black-doctors-health-disparity/2841925002/; and Shankar Vedantam et al., “People Like Us: How Our Identities Shape Health And Educational Success,” NPR: Hidden Brain, June 3, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/06/03/729275139/people-like-us-how-our-identities-shape-health-and-educational-success.

[70] Amy Harmon, “For a Black Mathematician, What It’s Like to Be the ‘Only One,’” New York Times, February 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/18/us/edray-goins-black-mathematicians.html.

[71] fwd.us, “Estimates of Family Incarceration by Race and Ethnicity,” https://everysecond.fwd.us/chapter-3/#chapter3-5 (accessed July 2019).

[72] Erica Williams et al., “Inclusive Approach to Immigrants Who Are Undocumented Can Help Families and States Prosper,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 19, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/inclusive-approach-to-immigrants-who-are-undocumented-can-help.

[73] Bill Hathaway, “Implicit bias may help explain high preschool expulsion rates for Black children,” Yale News, September 2016, https://news.yale.edu/2016/09/27/implicit-bias-may-explain-high-preschool-expulsion-rates-black-children.

[74] Shawn Fremstad and Melissa Boteach, “Valuing All Our Families,” Center for American Progress, January 2015, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2015/01/12/104149/valuing-all-our-families/.

[75] Justin Wolfers, David Leonhardt, and Kevin Quealy, “1.5 Million Missing Black Men,” New York Times, April 20, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/04/20/upshot/missing-black-men.html.

[76] Tamara Gilkes Borr, “How the War on Drugs Kept Black Men Out of College,” Atlantic, May 15, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/05/war-drugs-made-it-harder-black-men-attend-college/588724/.

[77] Raj Chetty et al., “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective,” NBER Working Paper No. 24441, revised June 2019, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/race/. Less than 5 percent of Black children grow up in areas with a poverty rate below 10 percent and where more than half of fathers are present, compared to 63 percent of white children. To be clear, the study stresses that it’s the presence of fathers in a neighborhood as a whole, as opposed to in each individual home, that appears linked to a child’s likelihood of success. Rather than prescribing any particular family structure, this would seem to reinforce the importance of children having access to a diverse pool of adult role models — whether a parent, neighbor, or otherwise — with different lived experiences. As the authors put it, “The association with father presence is driven by a characteristic of the neighborhood in which the child grows up, not simply a direct effect of the marital status of one’s own parents.”

[78] Sarada Sarada, Michael J. Andrews, and Nicolas L. Ziebarth, “Changes in the demographics of American inventors, 1870-1940,” Explorations in Economic History, October 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0014498318301888; and Bell et al., 2018.

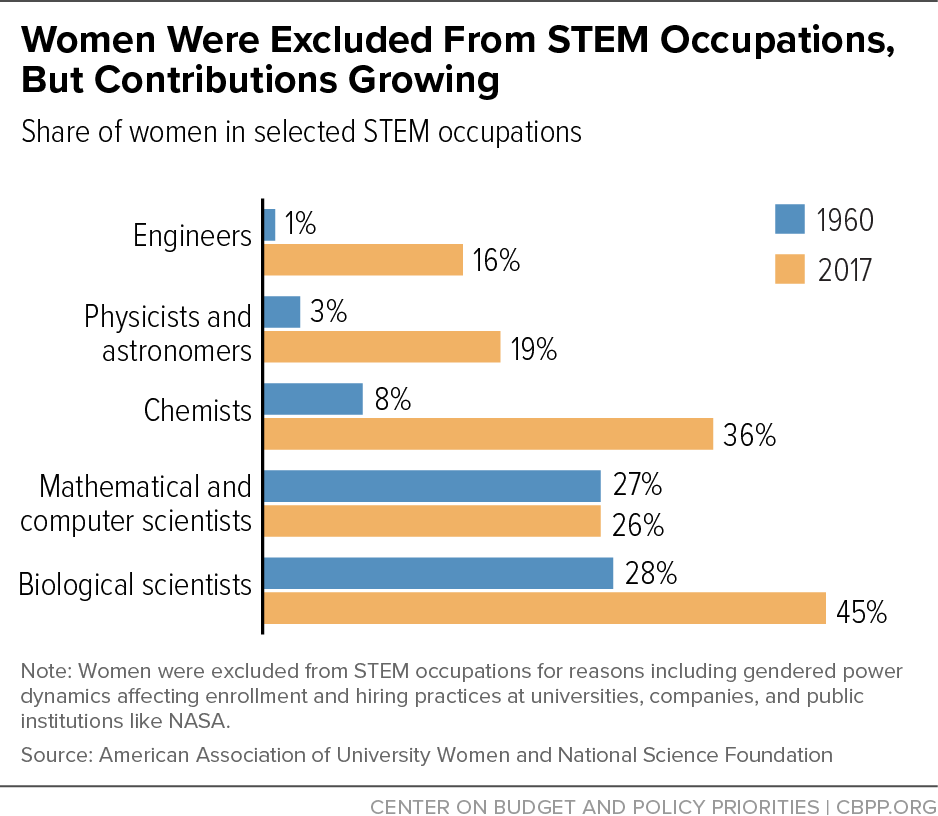

[79] Table S3-12, Employed Scientists and Engineers, by sex and occupation: 2017, “The State of U.S. Science and Engineering 2020,” National Science Board, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20198/data.

[80] NASA Office of Diversity and Equal Opportunity, “NASA Equal Employment Opportunity Strategic Plan: FY 2017-19: FY 2017 Annual Report and Update,” October 2018, https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy_2018_nasa_md-715_report_508.pdf.

[81] Christianne Corbett and Catherine Hill, “Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women’s Success in Engineering and Computing,” American Association of University Women, 2015, https://www.aauw.org/app/uploads/2020/03/Solving-the-Equation-report-nsa.pdf.

[82] National Women’s History Alliance, “Timeline of Legal History of Women in the United States,” https://nationalwomenshistoryalliance.org/resources/womens-rights-movement/detailed-timeline/ (accessed July 2019).

[83] Nina Banks, “Black women’s labor market history reveals deep-seated race and gender discrimination,” Economic Policy Institute, February 19, 2019, https://www.epi.org/blog/black-womens-labor-market-history-reveals-deep-seated-race-and-gender-discrimination/.

[84] Today, 78 percent of Black moms with children are employed compared with an average of just 66 percent of white, Asian American, and Latinx moms. Yet, in 2017, the median annual earnings for Black women working full time year-round was just over $36,000 — an amount 21 percent lower than white women. Valerie Wilson, “10 years after the start of the Great Recession, Black and Asian households have yet to recover lost income,” Economic Policy Institute, September 12, 2018, https://www.epi.org/blog/10-years-after-the-start-of-the-great-recession-black-and-asian-households-have-yet-to-recover-lost-income/.

[85] Catherine Hill, Christianne Corbett, and Andresse St. Rose, “Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics,” American Association of University Women, February 2010, https://www.aauw.org/app/uploads/2020/03/why-so-few-research.pdf.

[86] Association of American Medical Colleges, “Medical Students, Selected Years, 1965–2015,” https://www.aamc.org/download/481178/data/2015table1.pdf (accessed June 2019).

[87] Ernesto Reuben, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales, “How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 111, No. 12: 4403–08 (2014a).

[88] Recent research of standardized test scores for third- and eighth-graders in nearly every district in the country suggests that local norms may also play some role in disparities by gender. Specifically, while young girls perform better than boys on English tests regardless of their parents’ socioeconomic status, they tend to underperform boys in math but only in affluent communities. There is nearly no gender gap in math on average. Girls perform slightly better than boys in about a quarter of districts, particularly those that are predominantly African American and low income. Boys do slightly better in the rest, and much better in high-income and mostly white or Asian American districts. Claire Cain Miller and Kevin Quealy, “Where Boys Outperform Girls in Math: Rich, White and Suburban Districts,” New York Times, June 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/06/13/upshot/boys-girls-math-reading-tests.html.

[89] Joseph Cimpian, “How our education system undermines gender equity,” Brookings Institution, April 23, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2018/04/23/how-our-education-system-undermines-gender-equity/, and Joseph P. Robinson-Cimpian, Sarah Theule Lubienski, and Colleen M. Ganley, “Teachers’ Perception of Students’ Mathematics Proficiency May Exacerbate Early Gender Gaps in Achievement,” Developmental Psychology, Vol. 50, No. 4, 1262-1281, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0709/f13ba582e510689449b942610a5218761461.pdf.

[90] Janelle Gaines, “Women in Male-Dominated Careers,” Cornell HR Review, May 3, 2017, https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1099&context=chrr.

[91] Cimpian.

[92] The only low-innovation state today that does not meet this definition is West Virginia, which while technically part of slaveholding Virginia at the start of the Civil War, had negligible levels of slavery within its own territory.

[93] For one example, see Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen, “The Political Legacy of American Slavery,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 78, No. 3, May 2016, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/msen/files/slavery.pdf.

[94] Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas.

[95] See, for example, Alana Semuels “Why It’s So Hard to Get Ahead in the South,” Atlantic, April 4, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/04/south-mobility-charlotte/521763/; and Gareth Cook, “The Economist Who Would Fix the American Dream,” Atlantic, August 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/08/raj-chettys-american-dream/592804/.

[96] As the author notes, “More segregation corresponds to lower assigned-patent activity, whether considering total assigned patents or shares. Multiracial social networks, among other networks, became illegal, precarious, or infeasible. Increasing segregation, as measured by cumulative segregation laws, made some social networks illegal and others more precarious, which also erode previously integrated economic relations.” Cook, 2011, p. 19.

[97] See Rothwell, Perry, and Andrews.

[98] Nikole Hannah-Jones, “It Was Never About Busing,” New York Times, July 12, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/12/opinion/sunday/it-was-never-about-busing.html.

[99] Research Triangle Park, “The Transformative Impact of The Research Triangle Park — A Case Study,” February 15, 2018, https://www.rtp.org/transformative-impact-research-triangle-park-case-study/.

[100] Brian Lyman, “A permanent wound: How the slave tax warped Alabama finances,” Montgomery Advertiser, February 4, 2017, https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/politics/southunionstreet/2017/02/05/permanent-wound-how-slave-tax-warped-alabama-finances/97447706/.

[101] For more on this subject, see Trevor D. Logan, “Whitelashing: Black Politicians, Taxes, and Violence,” NBER Working Paper No. 26014, June 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26014; and Pavithra Suryanarayan and Steven White, “Slavery, Reconstruction, and Bureaucratic Capacity in the American South,” January 26, 2019, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2951964.

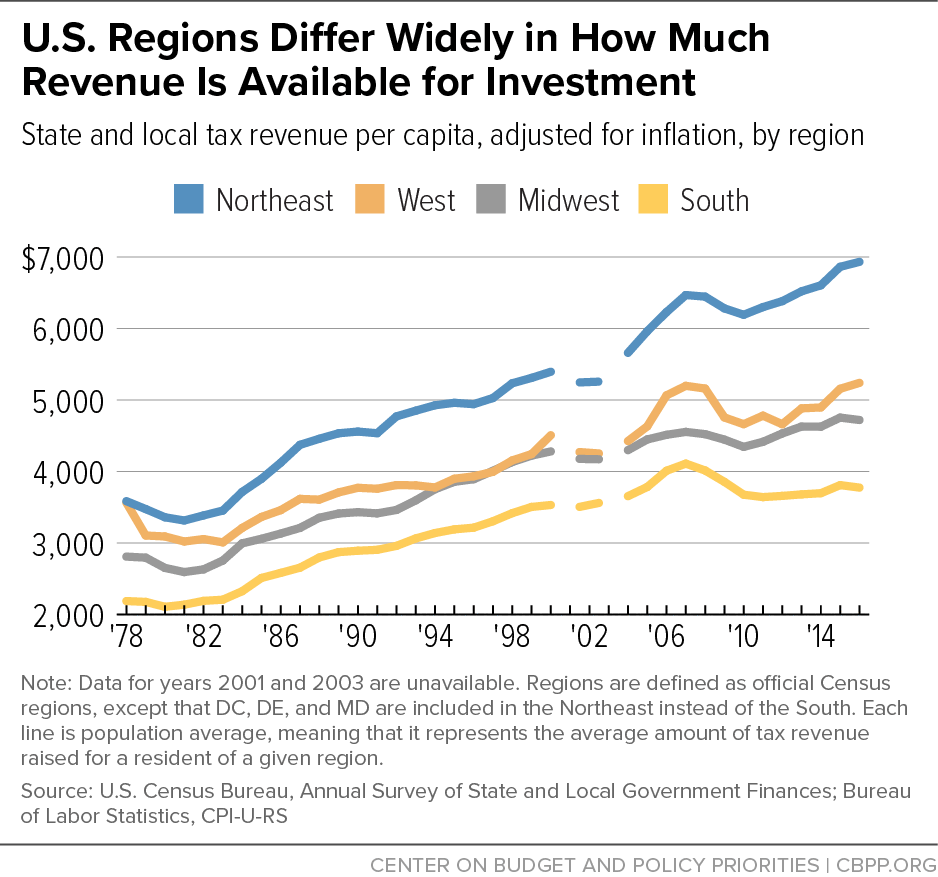

[102] The chart shows state and local tax revenue per capita from 1977 to 2016, adjusted for inflation. Each line is a population average, meaning that it represents the average tax revenue raised for a resident of a given region. This same regional trend in state and local tax revenue also appears in other metrics, including revenue as a share of GDP (1997-2016) and revenue as a share of personal income (1977-2016).

[103] See, for example, Daron Acemoglu, Ufuk Akcigit, and Murat Alp Celik, “Young, Restless and Creative: Openness to Disruption and Creative Innovations,” NBER Working Paper No. 19894, revised August 2015, https://www.nber.org/papers/w19894; and Richard Florida, “The Economic Geography of Talent,” Annals of Association of American Geographers, Vol. 92, No. 4, 2002, http://creativeclass.com/rfcgdb/articles/5%20The_Economic_Geography_of_Talent.pdf.

[104] Natalia Nollenberger, Núria Rodríguez-Planas, and Almudena Sevilla, “The Math Gender Gap: The Role of Culture,” American Economic Review, Vol. 106, No. 5, pp. 257-261, May 2016, https://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aecrev/v106y2016i5p257-61.html.

[105] Devin G. Pope and Justin R. Sydnor, “Geographic Variation in the Gender Differences in Test Scores,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 24, No. 2: 95-108, Spring 2010, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.24.2.95.

[106] As Chetty notes in an interview, “For whites, there are much lower rates of upward mobility throughout the South than you see in the rest of the country.” Ezra Klein, “You have a better chance of achieving ‘the American dream’ in Canada than in America,” Vox, August 15, 2019, https://www.vox.com/2019/8/15/20801907/raj-chetty-ezra-klein-social-mobility-opportunity.

[107] Edward J. Smith and Shaun R. Harper, “Disproportionate impact of K-12 school suspension and expulsion on Black students in southern states,” University of Pennsylvania, Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, 2015, https://web-app.usc.edu/web/rossier/publications/231/Smith%20and%20Harper%20(2015)-573.pdf.

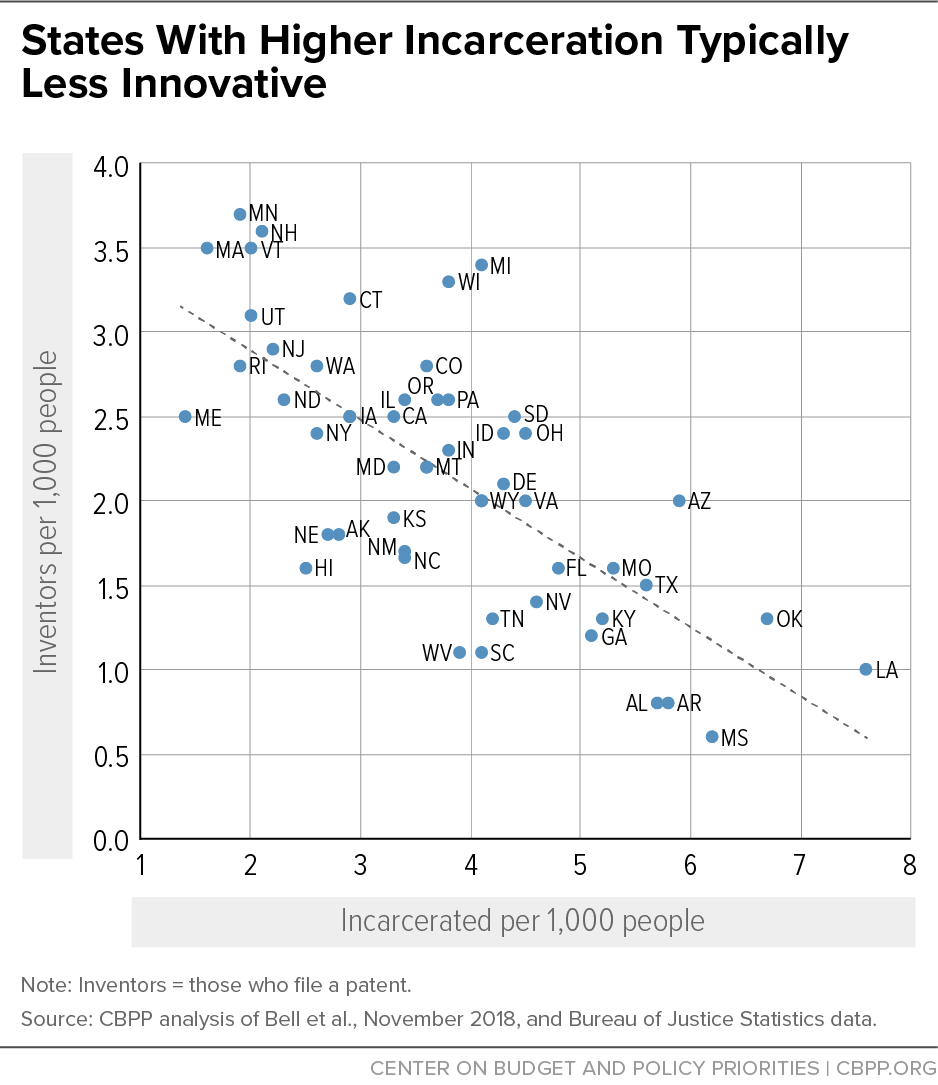

[108] CBPP analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics data.

[109] Thomas Breda et al., “Can female role models reduce the gender gap in science? Evidence from classroom interventions in French high schools,” PSE Working Papers halshs-01713068, HAL, 2018, https://ideas.repec.org/p/hal/psewpa/halshs-01713068.html.

[110] Charles M. Becker et al., “Can a summer make a difference? The impact of the American Economic Association Summer Program on minority student outcomes,” Economics of Education Review Vol. 53, pp: 46–71, 2016, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775715300819.

[111] Andy Reed, “Evolving tax incentives: A shared value approach to economic development in Portland,” Brookings Institution, May 29, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/05/29/evolving-tax-incentives-a-shared-value-approach-to-economic-development-in-portland/.

[112] Noah Smith, “America Lets Too Much Young Talent Go to Waste,” Bloomberg, February 6, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-02-06/america-neglects-talent-of-too-many-of-its-best-and-brightest.

[113] Michael Leachman and Eric Figueroa, “K-12 School Funding Up in Most 2018 Teacher-Protest States, But Still Well Below Decade Ago,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 6, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/k-12-school-funding-up-in-most-2018-teacher-protest-states-but-still.

[114] Louisa Diffey, “50-State Comparison: State Kindergarten-Through-Third-Grade Policies,” Education Commission of the States, June 2018, https://www.ecs.org/kindergarten-policies/.

[115] As of 2017, the share of 4-year-olds served ranges from over 75 percent in Oklahoma to just 10 percent in Arizona, and enrollment rates are far lower among 3-year-olds, even in the best-practice states.

[116] In other words, low-income children fall behind over the course of childhood and adolescence due to factors other than raw intelligence, such as neighborhood environment and education quality. Bell et al., 2018, p. 16.

[117] Jeff Guo, “These kids were geniuses — they were just too poor for anyone to discover them,” Washington Post, September 22, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/09/22/these-kids-were-geniuses-they-were-just-too-poor-for-anyone-to-discover-them/?noredirect=on.

[118] Bruce D. Baker, “Does Money Matter in Education?” Second Edition, Albert Shanker Institute, April 2019, http://www.shankerinstitute.org/resource/does-money-matter-second-edition.

[119] More specifically, this nationwide study examined the relationship between school funding and student outcomes from the early 1970s to 2011 and found that low-income children whose school districts received a 10 percent increase in per-pupil spending before they began their 12 years of public school had 10 percent higher earnings (and 17 percent higher family income) in adulthood, were likelier to complete high school, and were less likely as adults to be poor. C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker C. Johnson, and Claudia Persico, “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 131, Issue 1, February 1, 2016, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/131/1/157/2461148?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[120] California’s ambitious funding reform was paired with an influx of new revenues from a sizable tax increase, and appears to already be paying dividends for students and communities, in particular those of color. The formula appears to be producing substantial gains in educational outcomes for low-income students and students of color, which could have been greater if all districts had targeted all funding as intended to primarily benefit these populations. Learning Policy Institute, “California’s Local Control Funding Formula Is Increasing Student Achievement and Graduation Rates,” February 2, 2018, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/press-release/californias-local-control-funding-formula-increasing-student-achievement. See also Julia E. Koppich and Daniel C. Humphrey, “The Local Control Funding Formula (LCCF): What Have We Learned After Four Years of Implementation?” Getting Down to Facts II, September 2018, https://gettingdowntofacts.com/sites/default/files/2018-09/GDTFII_Report_Koppich-Humphrey.pdf.

[121] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “State Tax Codes as Poverty Fighting Tools: 2018 Update on Four Key Policies in All 50 States,” September 2018, https://itep.org/state-tax-codes-as-poverty-fighting-tools-2018/.

[122] Sullivan.

[123] See Gareth Olds, “Food Stamp Entrepreneurs,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 16-143, June 2016, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=50692; and Robert Fairlie et al., “Is Employer-Based Health Insurance a Barrier to Entrepreneurship?” American Society of Health Economists, June 2010, https://ssrn.com/abstract=1880523.

[124] Jun Koo, Young Jun Choi, and Iljoo Park, “Innovation and welfare: the marriage of an unlikely couple,” Policy and Society, August 2019, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14494035.2019.1641380.

[125] Michael Mitchell et al., “Unkept Promises: State Cuts to Higher Education Threaten Access and Equity,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 4, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/unkept-promises-state-cuts-to-higher-education-threaten-access-and.

[126] Otto Toivanen and Lotta Väänänen, “Education and Invention,” Center for Economic Policy Research, Discussion Paper No. 8537 (2011), http://aalto-econ.fi/toivanen/Toivanen_Vaananen_REStat16.pdf.

[127] The Lost Einsteins study suggests that strengthening local networks of innovation could provide a powerful tool over time — moving a child from an area at the 25th percentile of exposure to inventors, such as New Orleans, to one at the 75th percentile, such as Austin, Texas, would increase the child’s chances of growing up to invent by as much as 50 percent.

[128] Andre M. Perry and Rodney Sampson, “STEM talent exists in the South, but investment is appallingly lacking,” Brookings Institution, July 16, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2019/07/16/stem-talent-exists-in-the-south-but-investment-is-appallingly-lacking/. For one example of how strengthening HBCUs could help boost access to innovation, see Nikole Hannah-Jones, “A Prescription for More Black Doctors,” New York Times Magazine, September 9, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/13/magazine/a-prescription-for-more-black-doctors.html.

[129] Jonathan Gruber and Simon Johnson, “Policy Summary: Jump-Starting America,” 2019, https://www.jump-startingamerica.com/policy-summary.

[130] Hoxby and Avery.

[131] Scott Jaschik, “Attracting the Missing Students,” Inside Higher Ed, April 1, 2013, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/04/01/research-suggests-top-colleges-could-attract-many-more-high-achieving-low-income.

[132] That analysis found that people with a father or mother with a STEM Ph.D. are more than six times as likely to invent as those whose father or mother has only a base education (which the authors define as up to nine years of schooling), and that having a parent with a STEM instead of a non-STEM Ph.D. increases the probability to invent by more than 50 percent. Aghion et al., p. 39.

[133] Erin Sparks and Mary Jo Waits, “Growing State Economies: Twelve Actions,” National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, July 2012, https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/11HEINEMAN12ACTIONS.pdf. Also, while a full exploration of the issue is beyond the scope of this report, it is well established that women and people of color with entrepreneurial or innovative ideas face barriers to accessing venture capital and small business loans relative to their white male counterparts. Increased attention to this disparity by both policymakers and private lenders could help bolster equitable access to innovation as well. See Ben Hecht, “Why Entrepreneurs of Color Are Struggling,” CityLab, April 23, 2018, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/04/closing-the-racial-startup-gap/557012/.

[134] An estimated 25 percent of incubator clients on average are women and people of color, according to one estimate. JPMorgan Chase & Co. and the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, “Creating Inclusive High-Tech Incubators and Accelerators: Strategies to Increase Participation Rates of Women and Minority Entrepreneurs,” May 2016, http://icic.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/ICIC_JPMC_Incubators_updated_post.pdf.

[135] Ibid. For further reading on the St. Louis example, see Maria Altman, “Report highlights BioSTL as example for building on city’s strengths,” St. Louis Public Radio, June 27, 2017, https://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/report-highlights-biostl-example-building-city-s-strengths#stream/0. For more reading on additional models focused on enhancing access for women, see Elyse Shaw and Cynthia Hess, “Closing the Gender Gap in Patenting, Innovation, and Commercialization: Programs Promoting Equity and Inclusion,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, July 2018, https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/C471_Programs-promoting-equity_7.24.18_Final.pdf.

[136] Katherine W. Phillips, “How Diversity Makes Us Smarter,” Scientific American, October 1, 2014, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter/.

[137] Amy Stuart Wells, Lauren Fox, and Diana Cordova-Cobo, “How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students,” Century Foundation, February 9, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/?agreed=1&agreed=1. See also Century Foundation, “The Benefits of Socioeconomically and Racially Integrated Schools and Classrooms,” April 29, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/facts/the-benefits-of-socioeconomically-and-racially-integrated-schools-and-classrooms/.

[138] K.J.R. Phillips et al., “Integrated Schools, Integrated Futures? A Case Study of School Desegregation in Jefferson County, Kentucky,” in From the Courtroom to the Classroom: The Shifting Landscape of School Desegregation, C.E. Smrekar and E.B. Goldring eds., 2009, pp: 239-70.

[139] Rebekah Bastian, “How School Segregation Leads to Inequitable Career Opportunities: An Interview With Nikole Hannah-Jones,” Forbes, December 13, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/rebekahbastian/2019/12/13/how-school-segregation-leads-to-inequitable-career-opportunities-an-interview-with-nikole-hannah-jones/#3088732b52db.

[140] Sean F. Reardon et al., “Is Separate Still Unequal? New Evidence on School Segregation and Racial Academic Achievement Gaps,” Stanford Center for Policy Analysis, 2019, https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/separate-still-unequal-new-evidence-school-segregation-and-racial-academic-achievement-gaps.

[141] Racism and discriminatory public policies have played a central role in the creation and persistence of neighborhoods of extreme poverty, which are home primarily to people of color, particularly African Americans. These factors also contributed to the creation and persistence of high-opportunity neighborhoods, which are home primarily to white people. See, for instance, Rothstein and Sharkey, 2013, op. cit. For this reason, it is important to recognize that many of the characteristics of extreme-poverty neighborhoods that harm children’s health and chances of success are entangled with the forces of racism.

[142] Nationwide, districts that serve the most students of color receive about $1,800, or 13 percent, less per student than districts serving the fewest students of color. Ivy Morgan and Ary Amerikaner, “Funding Gaps: An Analysis of School Funding Equity Across the U.S. and Within Each State, 2018,” Education Trust, February 2018, https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/FundingGapReport_2018_FINAL.pdf.

[143] While we have much to learn about which interventions are effective in transforming low-income areas at a substantial scale, researchers have identified some successful examples of such changes, as well as promising efforts to improve outcomes for families in poor communities by targeting them with intensive services and supports for families. See, for example, Margery Austin Turner et al., “Opportunity Neighborhoods: Building the Foundation for Economic Mobility in America’s Metros,” US Partnership on Mobility From Poverty, February 2018, https://www.mobilitypartnership.org/opportunity-neighborhoods.

[144] State incarceration rates have risen primarily because states are sending a much larger share of offenders to prison and keeping them there longer. Michael Mitchell and Michael Leachman, “Changing Priorities: State Criminal Justice Reforms and Investments in Education,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 28, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/changing-priorities-state-criminal-justice-reforms-and-investments-in-education.

[145] Anne-Marie Slaughter, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” Atlantic, August 2012, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/07/why-women-still-cant-have-it-all/309020/.

[146] Dhruv Khullar, “Being a Doctor Is Hard. It’s Harder for Women,” New York Times, December 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/07/upshot/being-a-doctor-is-hard-its-harder-for-women.html.

[147] Bell et al., 2019.