Chairman Whitehouse, Ranking Member Grassley, and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Kathleen Romig; I am the director of Social Security and disability policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, an independent, nonprofit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income individuals and families.

Social Security, the nation’s most effective poverty reduction and social insurance program, faces a funding shortfall about a decade from now. It is critical that policymakers fill Social Security’s financing gap — and that they do so in a way that keeps the program’s promises to workers and beneficiaries and does more to protect people with low incomes from hardship.

Social Security is the cornerstone of U.S. economic security policy. It touches the lives of nearly every person nationwide, from the 183 million workers paying into the system to the 67 million retirees, survivors, disabled workers, and their families who are receiving benefits.[1] In the 87 years since its passage, Social Security has been tremendously successful, providing a foundation of income in retirement, dramatically reducing poverty, and financially protecting workers and their families against the financial risks of premature death or disability. Some key facts about Social Security’s critical impact include:

- Social Security is the largest source of income for most retirees. For 4 in 10 retirees, Social Security provides at least half of their income, and for 1 in 7 it provides at least 90 percent.[2]

- Social Security benefits are much more modest than many people realize. The average retirement benefit is about $1,800 per month, or about $22,000 per year. For a person with average earnings, retiring at age 65, Social Security benefits replace about 37 percent of past earnings — and that’s before Medicare premiums are deducted.[3]

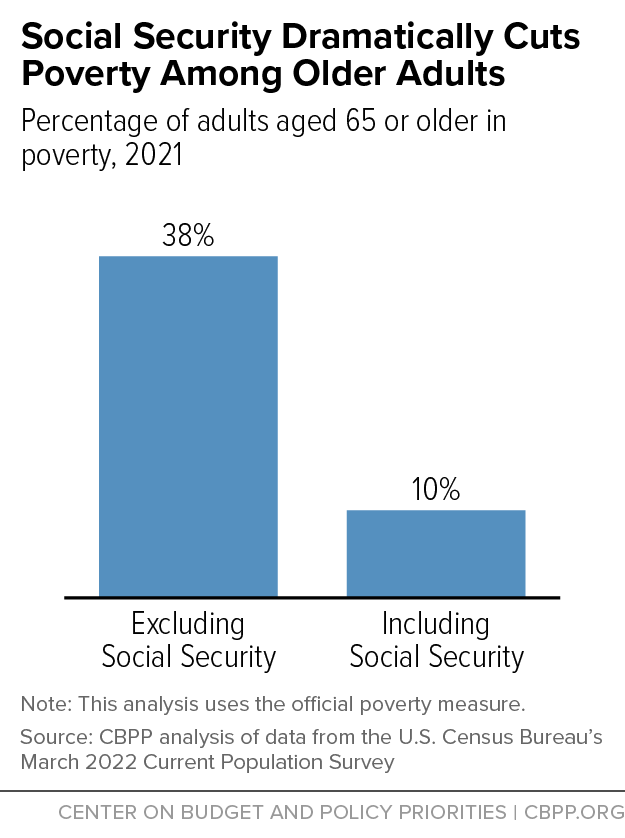

- Social Security benefits play a vital role in reducing poverty. Without Social Security benefits, a staggering 38 percent of older adults would have incomes below the poverty line, all else being equal; with Social Security benefits, 10 percent do, using the official poverty measure.[4] (See Figure 1.) Social Security benefits lift more than 22 million people above the poverty line, including 1 million children. Still, large numbers of seniors have modest incomes — 1 in 3 have incomes below twice the poverty line.

- Social Security is not just a retirement program. It also provides important life insurance and disability insurance protection. One in five beneficiaries receive disability benefits or are young survivors of workers who died prematurely.

- Social Security is especially important for people of color, who are more likely than white seniors to face financial insecurity in retirement due to persistent economic barriers, such as being more likely to be paid low wages, and less likely to be offered workplace retirement plans. Rates of disability and premature death are much higher for Black workers, in particular, than for other workers. The high rates of economic instability, disability, and premature death often have their roots in racism and other forms of discrimination that have systematically limited opportunity in education, labor market, and asset building.

In short, Social Security is critically important and vital to preserve for future generations. Despite sensational rhetoric, Social Security is not going bankrupt. However, it does face a long-term financing challenge. Though Social Security has amassed trust fund reserves of about $2.8 trillion, its costs are growing as more baby boomers retire. The program’s trustees estimate that, if policymakers take no further action, Social Security’s trust funds will be depleted in 2034. At that point, Social Security could still pay three-fourths of scheduled benefits, relying on Social Security taxes as they are collected. The long-term gap between Social Security’s projected income and promised benefits is estimated at 1.3 percent of GDP over the next 75 years, and the gap is fairly steady over the long term.

Alarmists who claim that Social Security won’t be around when today’s young workers retire either misunderstand or misrepresent the projections. However, policymakers must act to fully finance the Social Security program that people want and deserve. Senator Whitehouse’s Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act shows us that it is possible to shore up Social Security's financing without benefit cuts.

Social Security’s shortfall is real, but manageable. There are two primary ways to close the gap: cutting Social Security benefits or increasing contributions to the trust funds.

Cutting Social Security could hurt the millions of beneficiaries who rely on benefits as the foundation of their income. Because most retirees have modest incomes, save for some at the top of the income spectrum, most benefit cut proposals would reach low- and middle-income beneficiaries, undermining their financial security. About 1 in 4 older households live on incomes of less than $20,000; about half live on less than $50,000; more than 3 in 4 live on less than $100,000.[5] Most low-income older adults have very little pension income, if any.[6]

Some policymakers have proposed deep and broad Social Security cuts. For example, an often-discussed House Republican Study Committee proposal would raise Social Security’s full retirement age to 69 or 70, which would cut benefits by 20 percent. Raising the retirement age would cut benefits for all new retirees — and those cuts would fall hardest on lower- and middle-income beneficiaries because they rely most heavily on Social Security benefits. For example, a retiree with income at the 90th percentile receives, on average, about one-seventh of their income from Social Security, with ample income from pensions, earnings, or retirement accounts. A 20 percent cut in Social Security benefits for this retiree would result in just a 3 percent reduction in total income.[7] But for a retiree who relies solely on Social Security, a 20 percent benefit cut means a 20 percent reduction in total income. As this example makes clear, raising the age at which people receive full retirement benefits is a regressive benefit cut.

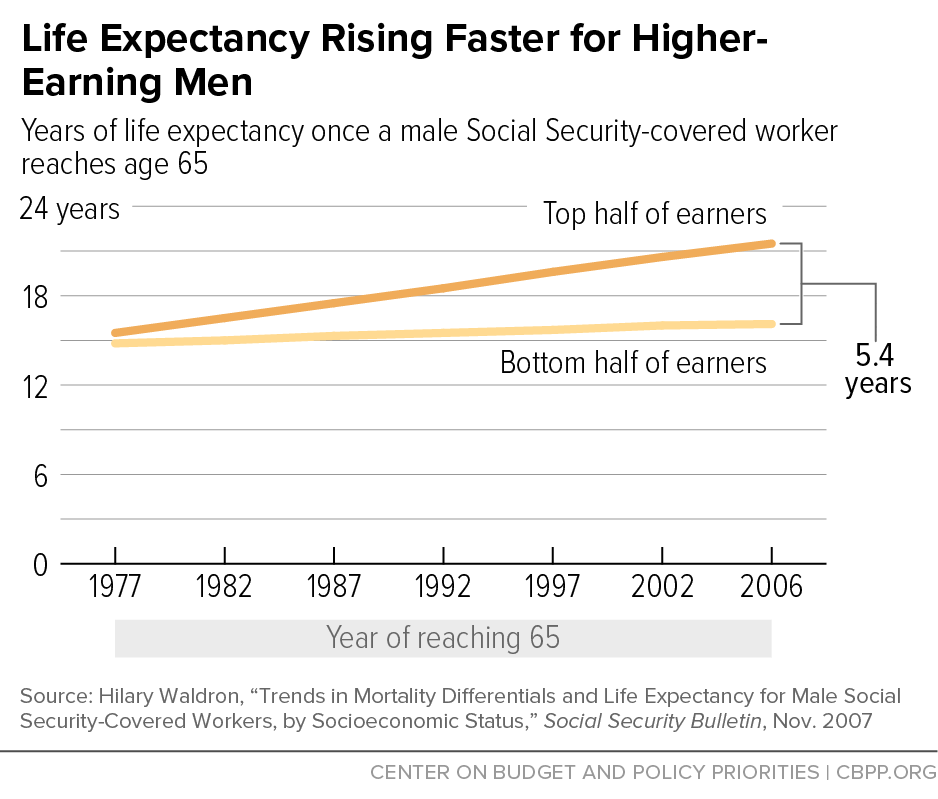

Proponents of raising the retirement age often justify the proposal by pointing to life expectancy gains, effectively arguing that people can expect to receive benefits for more years than previous generations did. However, low-income beneficiaries typically have not seen the life expectancy gains that higher-income people have experienced.

It’s also important to understand that benefit cuts would take many years to generate substantial savings for Social Security. If policymakers did choose to cut benefits, they would likely allow workers time to prepare for reduced benefits by exempting current and near-retirees and phasing in changes gradually. For example, many proponents of raising the retirement age would do so only for workers under 40 — or even under 30.[8] These cuts would not save any money for decades — but Social Security’s shortfall is about ten years away.

Policymakers should address Social Security’s long-term shortfall primarily by increasing Social Security’s tax revenues. Because the U.S. population is older than it was in previous generations, maintaining Social Security will necessarily require a larger share of our nation’s resources.

Trends over the past 40 years also justify boosting Social Security’s income — especially from those with high incomes and wealth, who can most afford to contribute more. Since the last time policymakers addressed Social Security financing, in 1983, inequality in the United States has skyrocketed — in longevity, in earnings, and especially in wealth. Policymakers should take these stark increases in inequality into account when deciding how to secure Social Security’s future:

- Higher-income people now enjoy significantly longer retirements. Among male workers, Figure 2 shows that longevity for the bottom half of earners has stagnated. Some groups are even living shorter lives than their parents or grandparents.[9] Longevity has also increased more among high-income women than lower-income women. Because of these differences, higher-income beneficiaries receive benefits for more years on average than lower-income beneficiaries. Longevity gains among high-income workers do not justify increasing the retirement age — and cutting benefits — for all.

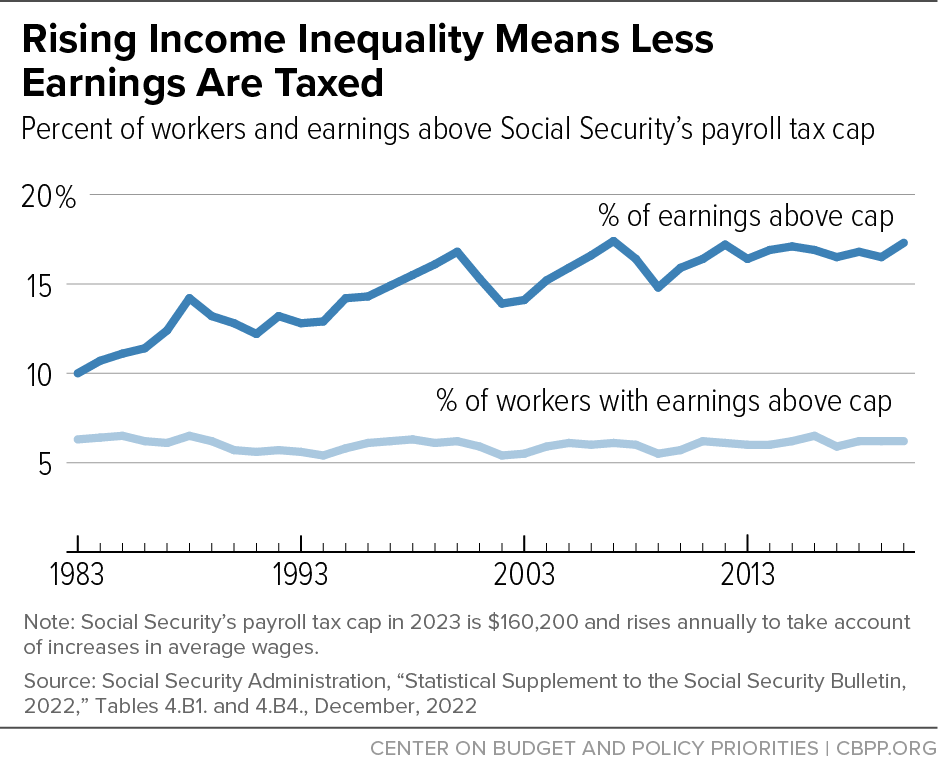

- Wages have grown more among high earners than middle and lower earners, even taking into account recent trends that have seen stronger wage growth among lower-paid workers. Earnings of the top 1 percent — and especially the top 0.1 percent — have grown rapidly, resulting in an increasing share of earnings above Social Security’s tax cap.[10] (See Figure 3.) This growing inequality should be addressed by expanding Social Security’s payroll tax base.

- A large and increasing share of the richest Americans’ income comes from investment and “pass-through” business income — not the paychecks that almost all other workers rely on, and from which Social Security gets the lion’s share of its funding.[11] As my colleagues at CBPP have explained, much of the income of very wealthy people is either not taxed or enjoys preferential rates.[12] The ultra-wealthy should pay more to address a broad range of the nation’s needs and create a fairer tax code, and shoring up Social Security could be one use for this revenue.

For these reasons, the majority of people in the U.S. — of all political stripes — oppose cuts to Social Security and support strengthening the program by raising more in taxes.[13]

While filling Social Security’s financing gap is a key task for policymakers, it is not enough. When policymakers update Social Security for the next generation, they should also improve benefits for those who need them most.

Social Security is a powerful anti-poverty program, lifting more people above the poverty line than any other government program. However, significant poverty and hardship remains among the older and disabled people Social Security is designed to help. The elderly poverty rate is 10 percent (6 million people), and the poverty rate among non-elderly adults with disabilities is even higher — 25 percent (4 million people).[14]

And even more beneficiaries are near poverty — almost 30 percent of seniors (16 million people) have incomes of less than 200 percent of the poverty line. Poverty is significantly higher among older women, because they tend to earn less than men, take more time out of the paid workforce, live longer, accumulate less savings, and receive smaller pensions.[15] Poverty among Black and Latino older adults is roughly two times as high as for older white adults, due in large part to a significant racial retirement wealth gap.

Social Security needs to be more generous to beneficiaries with the lowest incomes. Its “special minimum benefit” for long-term low earners failed to reach many poor seniors even at its peak, and today, because its value has dramatically eroded, it helps almost no one. Its design narrowly focused on long-term low earners, so it did little for low-income beneficiaries whose benefits are low because they had career interruptions, often because of caregiving, poor health, or job losses.

This group includes large numbers of women who took time out of the labor market to care for children as well as older or disabled family members. Women disproportionately provide unpaid family caregiving, which leads them to have lower Social Security benefits than men, contributing to higher poverty rates among female beneficiaries. To make a significant impact on poverty among seniors and disabled people, policymakers must target additional support to low-income beneficiaries whose benefits are low for a variety of reasons, not just persistent low wages.

In closing, now is the time to generate ideas to strengthen Social Security for generations to come. Senator Whitehouse’s new bill shows that raising revenue is key to protecting Social Security for future generations, without making devastating cuts that put people’s economic well-being at risk.

Thank you for inviting me to be part of the conversation about Social Security’s future.