The House of Representatives and the Senate Appropriations Committee have passed woefully inadequate funding plans for operating the Social Security Administration (SSA), which would substantially weaken customer service, hurting seniors and people with disabilities and hampering the agency’s ability to pay benefits promptly and accurately.

Years of SSA cuts have already taken their toll, leading to long waits on the phone and in field offices for taxpayers and beneficiaries, as well as record-high disability backlogs. Yet House-approved legislation would freeze SSA’s operating funds another year, even as the agency’s costs rise. Even worse, the Senate Appropriations Committee proposed another $400 million cut, nearly 4 percent of SSA’s operating budget — which would bring the total cut since 2010 to 16 percent, after inflation. The final 2018 appropriation needs to increase resources for basic operations to keep pace with inflation and the aging of the baby boomers.

SSA has already been forced to make cuts in customer service to operate under extremely tight budgets by closing field offices, shortening field office hours, and shrinking its staff. At the same time, it has saved money by increasing automation and reducing the number of Social Security statements that it sends. But these efficiencies can’t make up for the fact that SSA serves an additional 1 million beneficiaries each year. As workloads and costs grow and budgets shrink, SSA’s service has worsened by nearly every metric. Further cuts would force the agency to freeze hiring, furlough employees, shutter more field offices, or further restrict field office hours, leading to yet longer wait times for taxpayers and beneficiaries who need help.

The cuts would have been even deeper if Congress had not reached bipartisan agreements to ease sequestration in both defense and non-defense programs, starting in 2014. These temporary agreements only lasted through 2017, however, and SSA is very unlikely to receive adequate funding unless Congress once again reaches an agreement to reduce sequestration cuts.

During his campaign, President Trump repeatedly promised to protect Social Security, saying, “We’re not going to hurt the people who have been paying into Social Security their whole life.”[1] Protecting Social Security benefits, however, isn’t sufficient. Cuts to SSA operating funding are hurting hard-working people who have earned benefits and paid for high-quality service.

While the money to administer Social Security comes from workers’ contributions to Social Security — not from the general treasury — Congress sets a limit on the amount SSA may spend on its operations each year in the annual appropriations process.[2] The funds Congress allows SSA to spend, in turn, count against the tight funding limits on non-defense discretionary funding set by the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA), which were further lowered by sequestration, also put in place by the 2011 law. The BCA allows additional funding each year for SSA’s cost-saving program integrity activities such as continuing disability reviews (CDRs).[3] The tight funding caps required by the BCA and sequestration have been in place since 2012 and have forced cuts in a broad range of appropriated programs, including SSA operating funds.

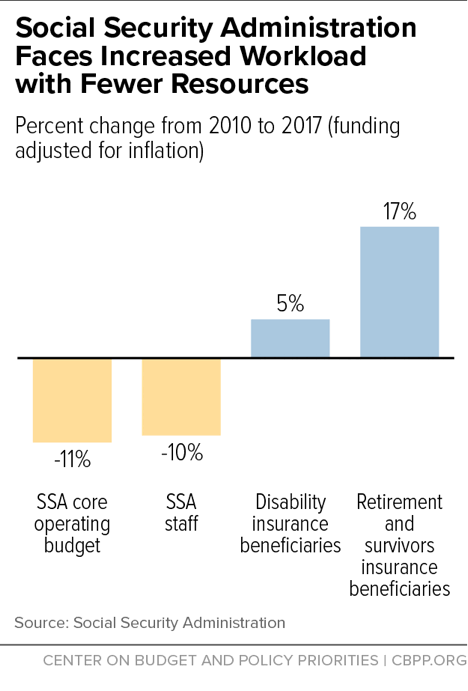

SSA’s operating budget shrank 11 percent from 2010 to 2017 in inflation-adjusted terms, just as the demands on SSA reached all-time highs as baby boomers reached their peak years for retirement and disability, as Figure 1 shows.[4] Budget cutting has squeezed SSA’s operating budget from an already low 0.9 percent of overall Social Security spending in 2010 to just 0.7 percent in 2016. The cuts have hampered SSA’s ability to perform its essential services, such as determining eligibility in a timely manner for retirement, survivor, and disability benefits; paying benefits accurately and on time; responding to questions from the public; and updating benefits promptly when circumstances change.

SSA’s 2017 appropriation provided the same funding for operating expenses as in 2016, plus $90 million in dedicated additional funding to hire the staff and make technological improvements needed to reduce the backlog in hearings for disability benefits — which helped, though the agency needed more than $150 million to implement its backlog reduction plan.

For 2018, the House has proposed flat funding, while the Senate Appropriations Committee has proposed cutting $400 million — nearly 4 percent — from SSA’s already inadequate operating budget. Even a small cut would have a noticeable negative impact on operations. SSA serves a growing population as baby boomers age — nearly a million more beneficiaries than a year ago.[5] In addition, SSA’s costs — for salaries, fringe benefits, contract services, rent, and so on — grow due to inflation, which flat funding also doesn’t cover. The agency has already cut significantly to operate under extremely tight budgets by closing field offices, shortening field office hours, and shrinking its staff. Further cuts would force the agency to freeze hiring, furlough employees, shutter more field offices, or further restrict field office hours, leading to yet longer wait times for taxpayers and beneficiaries who need help.

The public can conduct business at SSA field offices in almost every community in America. Social Security field staff assisted 43 million visitors in 2016.[6] People visit field offices to apply for benefits, replace lost Social Security cards, report changes in their names (due to a marriage or divorce, for example), and for other reasons.

Since the end of fiscal year 2016, SSA has lost over 1,000 field office staff, bringing the total loss since 2010 to 3,500.[7] Unless SSA gets adequate funding, staff losses will keep mounting. The budget cuts — and the intermittent hiring freezes that result — have taken a toll on customer service. Field offices must serve nearly the same number of visitors with fewer staff (and in fewer hours, because of previous cuts to field office hours).[8] Over 16,000 visitors to SSA’s field offices waited more than an hour for service each day in August 2017, and another 8,000 left without being served.[9] Visitors must wait weeks for an appointment. One in five calls to field offices go unanswered. As staff losses snowball, customer service will worsen.

SSA’s national toll-free telephone number is the gateway to the agency’s services, fielding an estimated 35 million calls in 2017. [10] Agents take claims for benefits, set up appointments, and answer questions about SSA’s programs; automated services are also available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

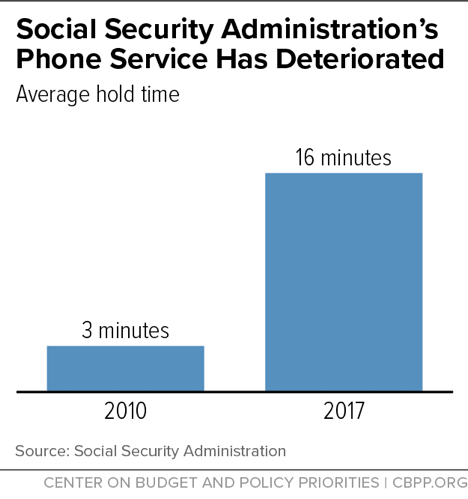

As of December 2016, SSA’s teleservice centers have 400 fewer agents than they need to handle current call volume.[11] Due to staff shortages, most callers to SSA’s national 800 number don’t get their questions resolved. Nearly half of callers hang up before connecting. Another 12 percent of callers get busy signals — compared to 5 percent in 2010.[12] For those who do get through, the average wait time to talk to an agent is over 16 minutes — compared to 3 minutes in 2010 (see Figure 2). Phone service has worsened considerably between 2016 and 2017.

SSA provides disability benefits through the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) programs to workers with impairments severe enough that they can’t support themselves and their families.[13] The average processing time for initial claims has held fairly steady in recent years at three to four months. Denied applicants who appeal — including many who ultimately qualify for benefits — must typically wait nearly two years before an administrative law judge decides their case.

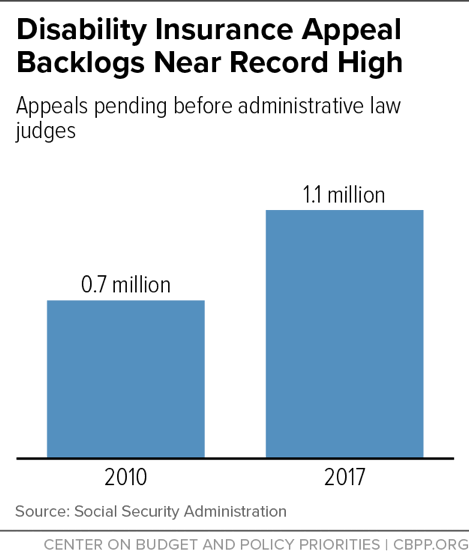

SSA rejected a record number of disability applicants during the Great Recession, and then struggled to decide the record-high number of appeals that followed on a shrinking budget, which caused hearings backlogs to mount. [14] The number of pending cases was shrinking until 2011 — the year of the Budget Control Act — but climbed nearly 60 percent, as Figure 3 shows, from about 700,000 in 2010 to about 1.1 million in 2017.[15] Meanwhile, the average wait for a hearing decision has reached an all-time high of 21 months in 2017.[16]

The hearings backlog has a high human cost. Waiting nearly two years for a final decision, as a typical appellant does, causes financial and medical hardship.[17] Some applicants lose their homes or must declare bankruptcy while waiting. Their health often worsens, and some die.[18]

SSA’s 2017 appropriation provided $90 million in dedicated funds to reduce the hearings backlog — which helped, but was far short of what the agency requested for its multi-year plan to eliminate the backlog and halve wait times. [19] Because of inadequate funding, SSA was forced to rewrite its backlog reduction plan, putting many initiatives on hold and delaying the target date for eliminating the backlog by two years, from 2020 to 2022. And hitting that delayed timeframe depends on a modest increase in funding in 2018, as proposed in the President’s budget.

To make significant progress on the disability appeals backlog, SSA must hire hundreds of new judges and the staff they need to write decisions, schedule hearings, compile files, and perform the other tasks needed to properly adjudicate claims and make accurate decisions. More hearings also will require more contracts with medical experts, vocational experts, and interpreters. In addition, SSA’s backlog reduction plan calls for management improvements, sophisticated data analytics, and IT investments. All of these improvements require more resources than the appropriations bills provide for.

Policymakers Can Spare Beneficiaries and Taxpayers Further Harm

With more investment, SSA can reduce its backlogs and improve service. Failing to invest in customer service, in contrast, is penny wise and pound foolish. As President George W. Bush’s Social Security Commissioner, Michael Astrue, told the Senate in 2012, “At some point, we will have to handle every claim that comes to us, every change of address, every direct deposit change, every workers’ compensation change, every request for new or replacement Social Security cards. The longer it takes us to get to this work, the more it costs to do.”