BEYOND THE NUMBERS

We’ve written a lot about the Social Security Disability Insurance program, which pays modest benefits (averaging $1,100 a month) to people who have worked substantially in the past but can’t anymore because of a severe and long-lasting medical impairment. But, in the face of continuing questions about the program, here’s something else to keep in mind:

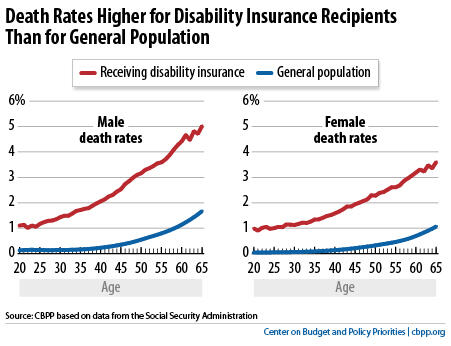

People who collect DI are at least three times as likely to die as other people their age (see chart).

For some DI recipients, the health diagnoses are bleak: cancer, emphysema, congestive heart failure or kidney failure. Many other recipients’ primary diagnoses, including mental disorders and impairments that affect their bones, muscles, and joints, aren’t usually fatal by themselves — though often recipients suffer from multiple conditions that can complicate their health.

Moreover, DI beneficiaries typically have low income, limited education, and a history of poor access to the health care system.

Here’s another way to look at their mortality: the Social Security actuaries estimate that about one-fifth of men who get DI, and nearly one-sixth of women, die within five years after they start collecting benefits.

(And an unknown, but significant, number die during the five-month waiting period, when DI benefits are unavailable and claimants must rely on sick leave, savings, help from family members, or — for the truly destitute — needs-tested Supplemental Security Income benefits. The very sickest applicants may get fast-track consideration under the compassionate allowances program, but even that process doesn’t waive the five-month wait.)

Many new beneficiaries have costly health care needs. DI recipients can obtain Medicare 24 months after they qualify for cash benefits, regardless of their age. A pilot study that offered selected beneficiaries medical coverage during that normal two-year wait found that the average participant cost $30,000, and 9 percent bumped against the pilot’s $100,000 ceiling.

DI’s critics should remember that it chiefly helps older workers with severe impairments, high health care costs, limited education and skills — and high mortality. In short, it works as policymakers intended.