- Home

- Poverty And Inequality

- House Relief Package Would Help Millions...

House Relief Package Would Help Millions and Bolster the Economy

CBPP Staff

The House’s emerging economic relief package would provide needed help to tens of millions of people, reduce high levels of hardship, help school districts address student learning loss, and bolster the economy. While some modifications will likely be made as the legislation is finalized, Congress should move quickly to enact a relief package that reflects the priorities in this package, which is modeled on President Biden’s American Rescue Plan.

The economy remains weak, the jobs recovery has lost momentum, and there are nearly 10 million fewer jobs than in February of 2020.The economy remains weak, the jobs recovery has lost momentum, and there are nearly 10 million fewer jobs than in February of 2020.[1] Black and Latino unemployment is 9.2 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively, well above the white unemployment rate of 5.7 percent — which itself is too high. The economy won’t return to its full potential until 2025, the Congressional Budget Office projects; the number of people employed won’t return to pre-pandemic levels until 2024; and unemployment won’t fall below 4 percent until 2026.[2]

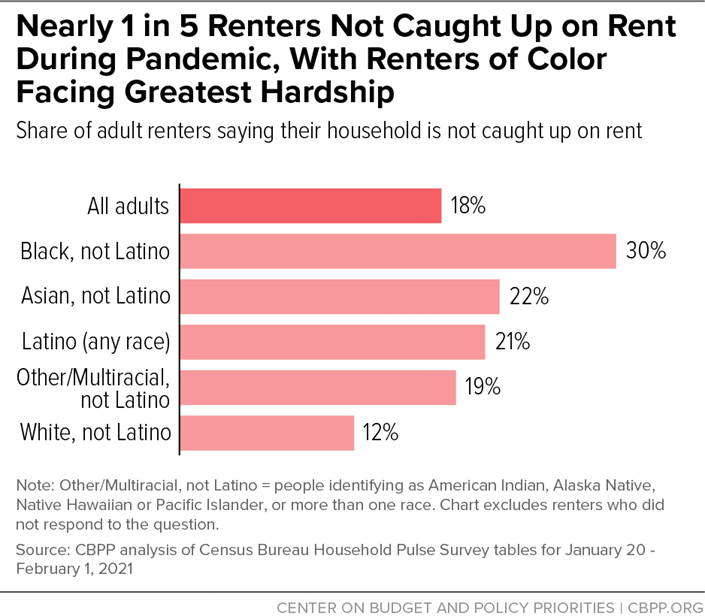

Hardship remains extraordinary; it’s particularly acute among Black, Latino, and Indigenous people and immigrants; and households with children also have been particularly hard hit.[3] Nearly 83 million adults (35 percent of all adults) reported between January 20 and February 1 that their household found it somewhat or very difficult to cover usual expenses in the past seven days, and that figure rises to 42 percent for adults living with children. Some 24 million adults (11 percent) said their household sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat, rising to 15 percent among adults in households with children. An estimated 13.2 million adults in rental housing (nearly 20 percent of adult renters) said they were not caught up on rent, rising to 26 percent among adult renters with children. The extent and severity of hunger, eviction, homelessness, and other hardship in the days ahead will depend on whether policymakers provide robust relief that reaches those in need (and on the pandemic’s trajectory and the economy’s pace of recovery).

It is critical that policymakers act to reduce high levels of hardship, take the public health steps needed to end the pandemic, and put the nation on the best possible path for a strong and equitable recovery.

The House package includes key provisions to meet these goals, including:

- Expanded and extended unemployment benefits;

- Expansions in the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit;

- Continuation of key food assistance provisions now in place and new investments in WIC;

- Expansions in health coverage;

- Increased housing assistance;

- Fiscal aid for states, territories, tribes, and localities;

- Funding for K-12 schools; and

- Emergency funds to help families facing hardship.

The package includes other provisions as well, including a new round of stimulus payments, public health investments, a minimum wage increase, paid leave provisions, additional child care funding, and aid to businesses. These are not covered in this paper.

Unemployment Benefits

The House package would extend critical unemployment benefits that are helping jobless workers pay their bills and care for their families.[4]

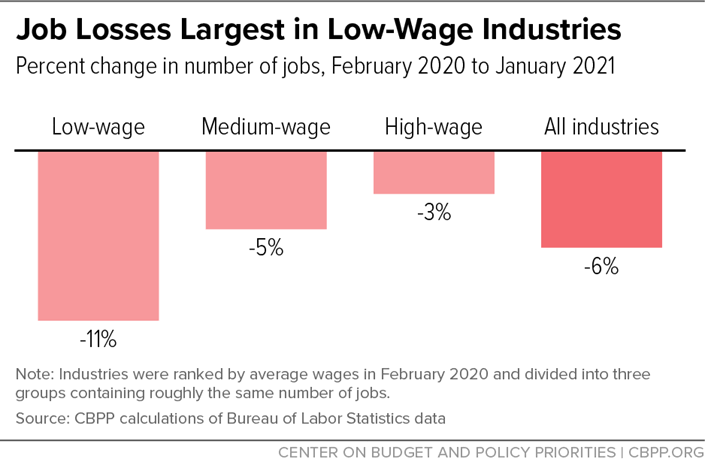

Not only are there now 9.9 million fewer jobs than in February of 2020, but a disproportionate number of job losses over the past year are in industries that pay low wages. (See Figure 1.) Since the steep job losses of last spring, workers of color and those without a bachelor’s degree have endured a far slower jobs recovery than white workers and college graduates. The lowest-paying industries accounted for 31 percent of all jobs in February of 2020, but 57 percent of jobs lost since then.

The December relief package reinstated a federal unemployment benefit increase, provided more weeks of benefits so that jobless workers wouldn’t lose them while the nation struggled with COVID-19 and its economic fallout, and continued the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which expands benefit eligibility to more jobless workers. These provisions are slated to expire in mid-March, and the House package would extend them to the end of August (and increase the federal benefit supplement, from $300 per week to $400). The August cutoff, however, is problematic compared to the end-of-September date in President Biden’s plan. Unemployment, particularly among workers of color and workers without a college degree, will likely remain elevated in the fall; extending benefits through September better aligns with a time when — unlike August — Congress will be in session and focused on budget matters (with the fiscal year ending on September 30) and thus well positioned to extend benefits if necessary. The August timing makes a benefit lapse, which would hurt families and disrupt states’ ability to administer jobless programs, likelier.

Tax Credits

The House package would make the full Child Tax Credit available to 27 million children in families with low or no income, increase the size of the Child Tax Credit, and provide an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for far more low-paid adults without minor children at home — driving a historic reduction in child poverty and providing timely income support for millions of people.[5] (See Appendix Tables 1 and 2 for state-by-state data.)

Together, the Child Tax Credit and EITC now lift more children above the poverty line (5.5 million) than any other program. The House package would make the full Child Tax Credit available to children in families with low or no earnings, raise the maximum credit from $2,000 to $3,000 per child and $3,600 for children under age 6, and extend the credit to 17-year-olds. The increase in the maximum amount would begin to phase out for heads of households making $112,500 and married couples making $150,000. The proposal would lift 4.1 million additional children above the poverty line — cutting the number of children in poverty by more than 40 percent — and lift 1.1 million children above half the poverty line (referred to as “deep poverty”). Among the children that the Child Tax Credit expansion would lift above the poverty line, some 1.2 million are Black, 1.7 million are Latino, 148,000 are Asian American, and 887,000 are white.[6]

The House package also would raise the EITC for low-paid working adults who are not raising children at home and now get only a tiny credit. It would raise the maximum EITC for these “childless adults” from about $530 to about $1,500, raise the income cap for them to qualify from about $16,000 to at least $21,000, and expand eligible childless workers to include younger adults aged 19-24 who aren’t full-time students and those 65 and over. That would provide timely income support to over 17 million people who work for low pay, including the 5.8 million childless workers aged 19-65 (excluding full-time students aged 19-23) who are now the lone group that the federal tax code taxes into, or deeper into, poverty.

These expansions would help push against racial disparities. Currently about half of all Black and Latino children get only a partial Child Tax Credit or no credit at all because their families’ incomes are too low to qualify for the full credit. This design flaw in the current Child Tax Credit comes on top of longstanding employment discrimination, unequal opportunity in education and housing, and other factors that leave more Black and Latino households struggling to make ends meet. Similarly, the current EITC for adults without minor children at home is tiny, leaving low-paid workers, who because of these inequities are disproportionately workers of color, with inadequate wage supplements.

Food Assistance

The House package would extend and expand nutrition assistance to help address today’s extraordinarily high levels of hunger and hardship.[7]

The number of households struggling to put enough food on the table spiked last spring due to COVID-19, remained nearly three times its pre-pandemic levels over the summer, and rose even higher in late 2020. Food hardship has disproportionately affected households with children, especially Black and Latino households. Between 7 and 11 million children live in a household in which the children didn’t eat enough in the last seven days because they couldn’t afford enough food, compared to 1.1 million children in December of 2019. The current figure includes 28 percent of children in Black and Latino households, compared to 10 percent in white households.

The House package would extend, through September, a 15 percent increase in SNAP benefits from December’s relief package that is slated to expire in June — likely before the economy has recovered and while food insecurity remains high. (See Appendix Table 3 for state-by-state impacts.) It would allow states to continue, through the summer, the Pandemic EBT (P-EBT) program, which provides grocery benefits to replace meals that children miss when they do not attend school or child care in person. Extending this benefit through the summer is important, providing a bridge to help families until school reopens, hopefully fully in-person, in September.

The package also would provide funds to modernize the WIC nutrition program for low-income women, infants, and children, support innovative service delivery, and temporarily raise the amount of fruit and vegetables that participants can get. These steps would improve a critical program that has been proven to boost health and cognitive outcomes for children but served fewer individuals in fiscal year 2020 than the prior year despite the surge in food hardship during the pandemic. And it would add $1 billion to the capped block grants for food assistance that Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands receive instead of SNAP, enabling them to better meet their residents’ food assistance needs over the next several years.

Health

The House package would make comprehensive health coverage more affordable and accessible for millions of people during the current crisis.[8]

Comprehensive health coverage is important under any circumstances because it improves people’s access to care, financial security, and health outcomes. But preserving and extending coverage is even more important now, during COVID-19 and its economic fallout, because it would shield families from financial hardship and support public health efforts, easing people’s access to testing, treatment, and vaccines. Those who have low incomes or are uninsured, in particular, have faced unprecedented challenges. The relief measures that policymakers enacted over the last year in response to COVID-19 and its fallout did not extend health coverage or make it more affordable.

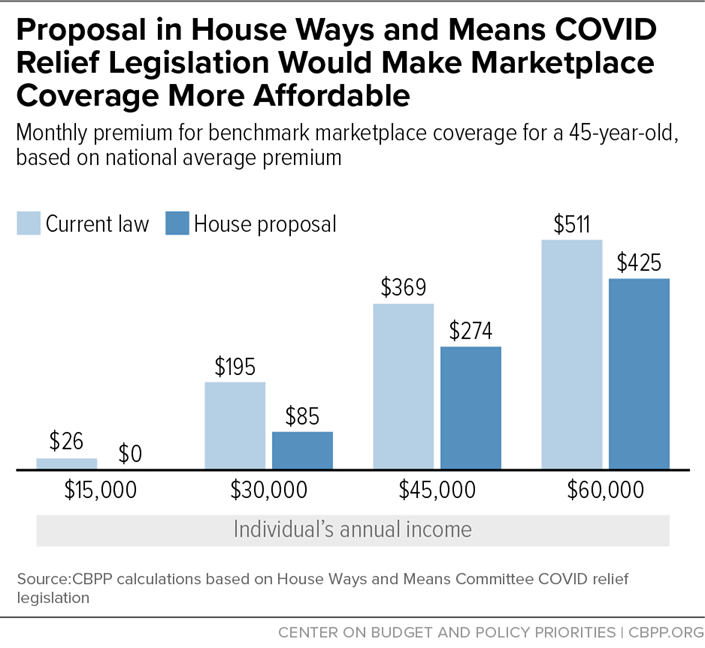

To make marketplace coverage more affordable, the House package would eliminate or vastly reduce premiums for many people with low or moderate incomes who enroll in plans through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces and would provide new help to people with somewhat higher incomes who face high premiums. (See Figure 2.) This provision would lower premiums for most current marketplace enrollees and expand coverage to 1.3 million people who would otherwise be uninsured.[9] In addition, the bill would improve affordability and decrease the number of uninsured people by:

- protecting marketplace enrollees, especially those whose income fluctuated last year, from having to repay large portions of their federal premium tax credits;

- making it easier for those getting unemployment benefits to afford coverage; and

- assisting people who recently lost their job and want to continue their current coverage to afford so-called “COBRA” coverage through September.

In addition, the package would increase financial incentives for the 14 states that have not implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to do so, which would provide critical coverage to nearly 4 million uninsured people (if all states adopted the expansion). And it would strengthen Medicaid coverage in other ways — for instance, with higher federal matching funds to help more people with disabilities get services in the community instead of nursing homes, with a new state option to extend Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage to 12 months after childbirth for postpartum people, and with letting Medicaid cover health services for the 30 days before people leave jail or prison to improve the coordination of their health services as they prepare to return home.

Housing

The House package includes critical housing assistance for millions who are struggling to pay rent and avoid eviction, and badly needed funds for communities to address homelessness during the pandemic.[10]

As noted, some 13.2 million adults — nearly 1 in 5 adult renters — report that they are not caught up on their rent, and renters likely already owe tens of billions in back rent and will need more help paying rent in the coming months. (See Figure 3.) Nearly 5 million renters say they have lost employment income and expect to be evicted soon. Struggling renters are disproportionately households with children and people of color, particularly people who are Black or Latino. Communities are struggling to provide safe, non-congregate shelter and housing options to the more than half-million people experiencing homelessness. Evictions and homelessness may exacerbate the spread of COVID-19 and cause severe hardship.

The House package provides critical relief to reduce evictions and other housing-related hardship. This relief will supplement $25 billion in rental assistance aid in December’s relief package (which will likely help only a fraction of those behind on rent) as well as the Biden Administration’s action to extend a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention order prohibiting most evictions through the end of March. The House package builds upon these efforts by providing $19 billion in emergency rental assistance for low-income renters who have lost income or are experiencing other hardship and risk losing their housing; $5 billion for Housing Choice Vouchers for people recovering from homelessness and for renters at greatest risk of homelessness; $5 billion for homelessness assistance through the HOME Investment Partnerships Program; $750 million in housing aid for tribal nations and Native Hawaiians; $139 million for rural housing assistance; and $100 million for housing counseling services for renters and homeowners. It also provides $10 billion to help homeowners who are experiencing financial hardship due to COVID-19 maintain their mortgage, tax, and utility payments and avoid foreclosure and displacement.

State Fiscal Aid

The House package would provide $350 billion to help states, localities, tribal governments, and territories address their sizable revenue shortfalls and added costs.[11]

State revenue for 2021 is down an estimated 6 percent below pre-pandemic projections, and municipal revenue fell 13 percent (and county revenue by a similar percentage) since COVID-19 hit. States, localities, tribal nations, and territories face $300 billion in total revenue shortfalls through fiscal 2022 (or $225 billion if they spend their $75 billion in reserves), but these estimates don’t include a host of pandemic-related state and local costs — fighting COVID-19 (e.g., with more protective equipment, testing, and tracing); providing services during the pandemic (e.g., by training and equipping public employees); and helping people and businesses facing extreme hardship (e.g., through emergency mental health programs and food assistance for families that need it).

Of the $350 billion in aid, states would get $195.3 billion. Each state would receive $500 million plus its share of the remainder based on its share of the nation’s jobless workers. Municipalities and counties would get $130.2 billion ($65.1 billion each) — with a municipality’s allocations based largely on its population and poverty, and county allocations based on each county’s share of the nation’s population. Tribal nations would get $20 billion, and territories would get $4.5 billion.

Schools

The House package includes President Biden’s proposal for $130 billion in new, flexible funds for school districts over the next three-and-a-half school years — the largest-ever one-time federal investment in K-12 education, but entirely appropriate in light of school funding needs and the impact the pandemic has had on student learning.[12]

Historically, K-12 schooling has been funded overwhelmingly by states and localities; they currently provide 92 percent of funding, with the federal government providing the rest. COVID-19, however, forced states to cut funding and created enormous financial and educational challenges that states and localities will be hard pressed to meet over the next several years without federal assistance. As noted, states, localities, tribal nations, and territories face a $300 billion revenue shortfall through fiscal 2022 that, if not offset with more federal funding, will mean more school funding cuts. K-12 funding comprises about 26 percent of state budgets and states will find it very hard to fully shield that funding while meeting their balanced-budget requirements. Even before COVID-19, schools endured years of inadequate and inequitable funding. Some 15-20 states were still providing less funding for K-12 schools when the pandemic hit than before the Great Recession of a decade ago in per-pupil, inflation-adjusted terms. When COVID-19 hit, schools were employing 77,000 fewer teachers and other workers while educating 1.5 million more children.

The CARES Act of March provided $13.2 billion for K-12 education and December’s package provided another $54 billion, but schools will need far more to pay for distance learning, safe in-person instruction, caring for students’ physical and mental health, and, most significantly, making up for learning loss. Schools need to close the “digital divide,” so all students and teachers have access to devices and connectivity. They need to safely operate in-person schools, which will require plexiglass shields, hand sanitizer, more custodial staff, and more buses and drivers to maintain social distancing. A quarter of schools have no full- or part-time nurse, and most schools lack counselling support to help students navigate the mental-health challenges of returning to school. Many schools will need to add staff and/or portable classrooms to reduce class size to meet social distancing guidelines.

But beyond the costs of operating remotely and in person, the House bill’s funds would enable school districts to make critical investments to address the widespread learning loss that the pandemic and remote learning have caused. Students on average will likely lose nine months of learning by the end of the 2020-21 school year, McKinsey & Company estimates, and students of color may well lose a full year on average. With resources, schools can lengthen school days and the school year and invest in high-quality tutoring to help students — over the course of the next couple of years — recover what they have lost. The costs of addressing all these needs could easily top $100 billion over the next few years, based on estimates from the Learning Policy Institute and McKinsey.[13] Along with the $130 billion, the House package includes “maintenance of equity” provisions that require states to avert funding cuts to schools and school districts with high numbers of poor children.

Emergency Funds

The House package includes a new $1 billion TANF Pandemic Emergency Fund to enable states, tribes, and territories to help families with the lowest incomes cover their additional pandemic-driven expenses and avert eviction and other real hardships.[14]

Hardship is particularly high among families with children, raising serious concerns about the long-term consequences for children’s health and academic outcomes. Nearly half of all children live in households that are having trouble covering usual expenses, and more than 4 in 10 children in rental housing live in a household that either isn’t getting enough to eat or isn’t caught up on rent.

States (along with tribes and territories) could use the new fund to provide households with non-recurrent, short-term benefits — that is, benefits that: (1) address a specific crisis or episode of need; (2) don’t meet recurring or ongoing needs; and (3) don’t extend beyond four months. States could direct funds to the families that most need them, and states need not limit payments to families receiving TANF cash assistance. Indeed, in states in which few families get TANF, states could reach more needy families by targeting a broader set of them (such as SNAP families with children). States also could use the funds, for instance, to help families that don’t get emergency housing assistance pay their back rent and avoid eviction, or help families fleeing domestic violence cover their moving costs and initial rental payments.

Appendix

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Number of Children Who Would Benefit From House Ways and Means Child Tax Credit Expansion, by State | |||||

| State | Children under 17 left out of the full $2,000 Child Tax Credit who would benefit from expansion | Children under 18 lifted above the poverty line by expansion | Children under 18 lifted above or closer to the poverty line by expansion | Children under 18 who would benefit from expansion | Share of children under 18 who would benefit from expansion |

| Total U.S. | 27,000,000 | 4,140,000 | 9,894,000 | 65,694,000 | 90% |

| Alabama | 479,000 | 80,000 | 162,000 | 1,021,000 | 94% |

| Alaska | 52,000 | 12,000 | 21,000 | 167,000 | 91% |

| Arizona | 690,000 | 112,000 | 238,000 | 1,508,000 | 93% |

| Arkansas | 324,000 | 48,000 | 94,000 | 661,000 | 94% |

| California | 3,527,000 | 553,000 | 1,689,000 | 7,865,000 | 88% |

| Colorado | 345,000 | 57,000 | 132,000 | 1,109,000 | 89% |

| Connecticut | 199,000 | 29,000 | 79,000 | 608,000 | 83% |

| Delaware | 67,000 | 10,000 | 24,000 | 183,000 | 90% |

| District of Columbia | 52,000 | 8,000 | 25,000 | 94,000 | 76% |

| Florida | 1,733,000 | 272,000 | 698,000 | 3,837,000 | 92% |

| Georgia | 1,042,000 | 171,000 | 354,000 | 2,274,000 | 91% |

| Hawai’i | 92,000 | 14,000 | 43,000 | 278,000 | 92% |

| Idaho | 154,000 | 17,000 | 37,000 | 410,000 | 94% |

| Illinois | 986,000 | 153,000 | 338,000 | 2,543,000 | 89% |

| Indiana | 556,000 | 80,000 | 175,000 | 1,453,000 | 93% |

| Iowa | 198,000 | 25,000 | 48,000 | 669,000 | 93% |

| Kansas | 219,000 | 29,000 | 57,000 | 652,000 | 93% |

| Kentucky | 421,000 | 69,000 | 143,000 | 931,000 | 93% |

| Louisiana | 529,000 | 94,000 | 188,000 | 1,028,000 | 94% |

| Maine | 75,000 | 10,000 | 21,000 | 229,000 | 91% |

| Maryland | 353,000 | 52,000 | 158,000 | 1,125,000 | 85% |

| Massachusetts | 355,000 | 55,000 | 161,000 | 1,105,000 | 81% |

| Michigan | 810,000 | 117,000 | 249,000 | 1,970,000 | 92% |

| Minnesota | 321,000 | 44,000 | 85,000 | 1,126,000 | 88% |

| Mississippi | 350,000 | 57,000 | 116,000 | 677,000 | 96% |

| Missouri | 505,000 | 73,000 | 153,000 | 1,262,000 | 92% |

| Montana | 78,000 | 10,000 | 21,000 | 210,000 | 93% |

| Nebraska | 141,000 | 18,000 | 36,000 | 434,000 | 93% |

| Nevada | 272,000 | 40,000 | 86,000 | 634,000 | 94% |

| New Hampshire | 52,000 | 8,000 | 20,000 | 222,000 | 87% |

| New Jersey | 560,000 | 89,000 | 257,000 | 1,608,000 | 82% |

| New Mexico | 244,000 | 32,000 | 71,000 | 454,000 | 95% |

| New York | 1,546,000 | 242,000 | 680,000 | 3,564,000 | 87% |

| North Carolina | 924,000 | 137,000 | 307,000 | 2,088,000 | 92% |

| North Dakota | 40,000 | 4,000 | 10,000 | 157,000 | 92% |

| Ohio | 948,000 | 132,000 | 278,000 | 2,372,000 | 92% |

| Oklahoma | 398,000 | 63,000 | 113,000 | 895,000 | 94% |

| Oregon | 292,000 | 40,000 | 92,000 | 779,000 | 90% |

| Pennsylvania | 892,000 | 140,000 | 311,000 | 2,368,000 | 90% |

| Rhode Island | 67,000 | 8,000 | 23,000 | 185,000 | 91% |

| South Carolina | 475,000 | 68,000 | 151,000 | 1,025,000 | 94% |

| South Dakota | 67,000 | 10,000 | 19,000 | 197,000 | 93% |

| Tennessee | 633,000 | 95,000 | 212,000 | 1,394,000 | 93% |

| Texas | 3,091,000 | 503,000 | 1,079,000 | 6,696,000 | 92% |

| Utah | 235,000 | 32,000 | 69,000 | 860,000 | 94% |

| Vermont | 30,000 | 4,000 | 8,000 | 105,000 | 91% |

| Virginia | 530,000 | 85,000 | 249,000 | 1,591,000 | 86% |

| Washington | 478,000 | 66,000 | 159,000 | 1,437,000 | 88% |

| West Virginia | 169,000 | 23,000 | 50,000 | 346,000 | 94% |

| Wisconsin | 368,000 | 46,000 | 94,000 | 1,159,000 | 92% |

| Wyoming | 35,000 | 3,000 | 11,000 | 128,000 | 95% |

Notes: Based on economy as of 2016-2018 using tax year 2020 tax rules and incomes adjusted to 2020 dollars. Children left out receive less than full $2,000 per child because their parents lack earnings or have earnings that are too low.

Source: For children left out of the full $2,000 Child Tax Credit, Tax Policy Center national estimate allocated by state based on CBPP analysis of American Community Survey (ACS) data for 2016-2018. For remaining columns, CBPP analysis of the March 2019 Current Population Survey (national estimate) allocated by state based on CBPP analysis of ACS data for 2016-2018. Poverty calculations also use U.S. Census Bureau Supplemental Poverty Measure research files for the ACS.

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 | |

|---|---|

| Childless Workers Who Would Benefit From House Ways and Means EITC Expansion, by State | |

| State | Estimated Number of Childless Workers Benefiting From EITC Expansion |

| Total U.S. | 17,354,000 |

| Alabama | 288,000 |

| Alaska | 41,000 |

| Arizona | 381,000 |

| Arkansas | 184,000 |

| California | 1,847,000 |

| Colorado | 299,000 |

| Connecticut | 154,000 |

| Delaware | 49,000 |

| District of Columbia | 33,000 |

| Florida | 1,310,000 |

| Georgia | 572,000 |

| Hawai’i | 69,000 |

| Idaho | 109,000 |

| Illinois | 620,000 |

| Indiana | 383,000 |

| Iowa | 181,000 |

| Kansas | 169,000 |

| Kentucky | 272,000 |

| Louisiana | 298,000 |

| Maine | 93,000 |

| Maryland | 257,000 |

| Massachusetts | 294,000 |

| Michigan | 603,000 |

| Minnesota | 289,000 |

| Mississippi | 177,000 |

| Missouri | 361,000 |

| Montana | 84,000 |

| Nebraska | 104,000 |

| Nevada | 169,000 |

| New Hampshire | 71,000 |

| New Jersey | 356,000 |

| New Mexico | 135,000 |

| New York | 915,000 |

| North Carolina | 603,000 |

| North Dakota | 41,000 |

| Ohio | 695,000 |

| Oklahoma | 237,000 |

| Oregon | 264,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 700,000 |

| Rhode Island | 49,000 |

| South Carolina | 317,000 |

| South Dakota | 53,000 |

| Tennessee | 396,000 |

| Texas | 1,404,000 |

| Utah | 139,000 |

| Vermont | 40,000 |

| Virginia | 419,000 |

| Washington | 360,000 |

| West Virginia | 111,000 |

| Wisconsin | 321,000 |

| Wyoming | 38,000 |

Note: Childless workers who would benefit from the House EITC expansion are those aged 19 and over (excluding full-time students 19-24).

Source: CBPP estimates based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016-2018 American Community Survey and March 2019 Current Population Survey, using 2020 tax parameters and incomes adjusted to 2020 dollars.

| APPENDIX TABLE 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Increase in SNAP Benefits, by State, From 15 Percent Increase in Maximum Benefit | |||||

| Under a 15% Increase in SNAP Maximum Benefits | |||||

| State | Number of SNAP Participants in Latest Month With Available Dataa (thousands) | Average Monthly Benefit Increase Per Person | Estimated Total Monthly Benefit Increase Statewide (millions) | Estimated Total 3-month Benefit Increase Statewide (millions) | Share of Increase Going to Households With Income Below 50 Percent of Federal Poverty Level |

| Alabama | 794 | $27 | $21 | $64 | 43% |

| Alaska | 74 | $37 | $3 | $8 | 50% |

| Arizona | 909 | $27 | $24 | $73 | 45% |

| Arkansas | 392 | $27 | $11 | $32 | 40% |

| California | 4,305 | $27 | $117 | $351 | 53% |

| Colorado | 498 | $27 | $14 | $41 | 40% |

| Connecticut | 365 | $28 | $10 | $30 | 34% |

| Delaware | 126 | $27 | $3 | $10 | 37% |

| District of Columbia | 132 | $28 | $4 | $11 | 60% |

| Florida | 3,505 | $27 | $96 | $289 | 31% |

| Georgia | 1,875 | $27 | $51 | $152 | 47% |

| Hawaii | 179 | $50 | $9 | $27 | 38% |

| Idaho | 138 | $27 | $4 | $11 | 34% |

| Illinois | 1,905 | $27 | $52 | $155 | 41% |

| Indiana | 664 | $27 | $18 | $53 | 38% |

| Iowa | 377 | $27 | $10 | $31 | 34% |

| Kansas | 202 | $27 | $5 | $16 | 36% |

| Kentucky | 628 | $27 | $17 | $51 | 45% |

| Louisiana | 1,013 | $27 | $27 | $82 | 50% |

| Maine | 157 | $27 | $4 | $13 | 20% |

| Maryland | 798 | $27 | $22 | $66 | 36% |

| Massachusetts | 890 | $28 | $25 | $74 | 33% |

| Michigan | 1,264 | $27 | $35 | $104 | 33% |

| Minnesota | 442 | $27 | $12 | $36 | 35% |

| Mississippi | 423 | $27 | $11 | $34 | 44% |

| Missouri | 702 | $27 | $19 | $57 | 41% |

| Montana | 96 | $27 | $3 | $8 | 34% |

| Nebraska | 154 | $27 | $4 | $12 | 37% |

| Nevada | 484 | $27 | $13 | $39 | 42% |

| New Hampshire | 70 | $27 | $2 | $6 | 18% |

| New Jersey | 788 | $27 | $21 | $64 | 27% |

| New Mexico | 448 | $27 | $12 | $36 | 40% |

| New York | 2,743 | $28 | $76 | $227 | 28% |

| North Carolina | 1,463 | $27 | $40 | $119 | 39% |

| North Dakota | 47 | $27 | $1 | $4 | 40% |

| Ohio | 1,401 | $27 | $38 | $114 | 36% |

| Oklahoma | 626 | $27 | $17 | $50 | 46% |

| Oregon | 671 | $28 | $19 | $56 | 38% |

| Pennsylvania | 1,834 | $27 | $50 | $151 | 29% |

| Rhode Island | 138 | $28 | $4 | $12 | 37% |

| South Carolina | 604 | $27 | $16 | $49 | 45% |

| South Dakota | 76 | $27 | $2 | $6 | 43% |

| Tennessee | 912 | $27 | $25 | $74 | 48% |

| Texas | 3,703 | $27 | $99 | $296 | 43% |

| Utah | 171 | $26 | $5 | $14 | 39% |

| Vermont | 68 | $28 | $2 | $6 | 18% |

| Virginia | 753 | $27 | $20 | $61 | 43% |

| Washington | 951 | $28 | $26 | $79 | 34% |

| West Virginia | 305 | $27 | $8 | $25 | 44% |

| Wisconsin | 738 | $27 | $20 | $60 | 30% |

| Wyoming | 28 | $27 | $1 | $2 | 39% |

| Guam | 46 | $38 | $2 | $5 | 44% |

| Virgin Islands | 25 | $35 | $1 | $3 | 65% |

Notes:

a The latest month for which USDA has published data on the number of SNAP participants in every state is September 2020. For many states, however, we have compiled more recent data from publicly available information. The figures in this table are the most recent available for each state as of early February, except that we use the USDA September 2020 figure if the state-reported data differ substantially from the USDA data.

Sources: CBPP analysis of fiscal year 2018 SNAP USDA Household Characteristics data and recent administrative data that states post publicly or report to USDA, https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap.

End Notes

[1] Chad Stone, “Jobs Recovery Still Long Way Off, Especially for Low-Wage Workers and Workers of Color,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 5, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/jobs-recovery-still-long-way-off-especially-for-low-wage-workers-and-workers-of-color.

[2] Joel Friedman, “Budget Resolution Marks Important Step Toward Urgently Needed COVID Relief,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 3, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/budget-resolution-marks-important-step-toward-urgently-needed-covid-relief.

[3] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships,” updated February 11, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and.

[4] Chad Stone, “COVID Relief Package Includes Important Unemployment Benefit Extensions, But Duration Should Be Extended,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 9, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/covid-relief-package-includes-important-unemployment-benefit-extensions-but-duration-should-be.

[5] Chuck Marr et al., “House Ways and Means COVID Relief Bill Includes Critical Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 9, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/house-ways-and-means-covid-relief-bill-includes-critical-expansions-of-child.

[6] Racial and ethnic categories do not overlap. Figures for each racial group such as Black or Asian American do not include individuals who identify as people of Latino ethnicity. Latino includes all people of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin regardless of race. Figures for children who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) alone are not shown because of concerns about sample size and data reliability and because limiting the figures to a single race and ethnicity has particularly strong implications for the estimated size of the AIAN population. About 180,000 children who identify as AIAN alone or in combination, regardless of Latino ethnicity, would be lifted above the poverty line by the House’s Child Tax Credit expansion. Following the mutually exclusive approach used for other racial and ethnic groups, about 70,000 children who identify as AIAN alone, not Latino, would be lifted above the poverty line by the House’s Child Tax Credit expansion.

[7] Joseph Llobrera, “COVID Relief Bills Respond to Extraordinarily High Food Hardship,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 9, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/covid-relief-bills-respond-to-extraordinarily-high-food-hardship; Dottie Rosenbaum et al., “Food Assistance in COVID Relief Bills Would Reduce Hardship, Provide Economic Stimulus,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 10, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/food-assistance-in-covid-relief-bills-would-reduce-hardship-provide.

[8] Sarah Lueck, “Bigger Tax Credits, More Medicaid Expansion Would Make Health Coverage More Accessible and Affordable,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 10, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/bigger-tax-credits-more-medicaid-expansion-would-make-health-coverage-more-accessible-and; Tara Straw et al., “Health Provisions in House Relief Bill Would Improve Access to Health Coverage During COVID Crisis,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 10, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/health-provisions-in-house-relief-bill-would-improve-access-to-health-coverage.

[9] Congressional Budget Office, “Reconciliation Instructions of the House Committee on Ways and Means,” Cost Estimate, February 15, 2021, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-02/hwaysandmeansreconciliation.pdf.

[10] Douglas Rice and Ann Oliva, “Housing Assistance in House COVID Bill Would Prevent Millions of Evictions, Help People Experiencing Homelessness,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 8, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/housing-assistance-in-house-covid-bill-would-prevent-millions-of-evictions-help.

[11] Michael Leachman, “House Budget Bill Provides Needed Fiscal Aid for States, Localities, Tribal Nations, and Territories,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 10, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/house-budget-bill-provides-needed-fiscal-aid-for-states-localities.

[12] Nicholas Johnson and Victoria Jackson, “House Bill to Implement Biden COVID-Relief Plan Includes Much-Needed K-12 Funding,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 9, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/house-bill-to-implement-biden-covid-relief-plan-includes-much-needed.

[13] Emma Dorn et al., “COVID-19 and Learning Loss — Disparities Grow and Students Need Help,” McKinsey & Company, December 8, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-learning-loss-disparities-grow-and-students-need-help; Michael Griffith, “What Will It Take to Stabilize Schools in the Time of COVID-19?” Learning Policy Institute, May 7, 2020, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/what-will-it-take-stabilize-schools-time-covid-19.

[14] LaDonna Pavetti, “Pandemic Emergency Fund Would Help Families With Lowest Incomes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 10, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/pandemic-emergency-fund-would-help-families-with-lowest-incomes.